Coxen's Fig-Parrot Cyclopsitta Diophthalma Coxeni Recovery Plan 2001−2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

PLANT COMMUNITY FIELD GUIDE Introduction to Rainforest

PLANT COMMUNITY FIELD GUIDE Introduction to Rainforest Communities Table of Contents (click to go to page) HCCREMS Mapping ....................................................................... 3 Field Data Sheet ............................................................................. 4 Which of the following descriptions best describes your site? ................................................................ 5 Which plant community is it? .......................................................... 9 Rainforest communities of the Lower Hunter .................................. 11 Common Rainforest Species of the Lower Hunter ........................................................................ 14 A picture guide to common rainforest species of the Lower Hunter ........................................................... 17 Weeding of Rainforest Remnants ................................................... 25 Rainforest Regeneration near Black Jacks Point ............................ 27 Protection of Rainforest Remnants in the Lower Hunter & the Re-establishment of Diverse, Indigenous Plant Communities ... 28 Guidelines for a rainforest remnant planting program ..................... 31 Threatened Species ....................................................................... 36 References ..................................................................................... 43 Acknowledgements......................................................................... 43 Image Credits ................................................................................ -

Appendix 3G Further Perspectives on the Financial Benefits of Local Government Amalgamations

3G-1 Appendix 3G Further Perspectives on the Financial Benefits of Local Government Amalgamations Appendix 3G has five sections which support the section in Chapter 3 on estimates of the financial benefits of local government amalgamations. The first section further examines the KPMG estimates that savings of up to $845 million per annum could be achieved in NSW through local government amalgamations. This first section also includes a critique of the KPMG estimates by Judith McNeill. The second section presents a Darwinian survival perspective to the debate on the preferred sizes of local governments. The third section briefly discusses the self-limiting effect whereby the strength of the argument in favour of local government amalgamations must in some senses diminish with each successfully achieved amalgamation. The fourth section, in Table 3G-3, provides a compilation of extracts from 113 Australian and international literature sources which provide valuable insights on the local government amalgamation debate generally and which appear to provide important lessons for this current study. KPMG's Financial Benefit Estimates Consultants KPMG explored four local government amalgamation options, and establishes estimates of cost savings possible through each of these options, in a 1998 report prepared for the Property Council of NSW. Table 3G-1 below summarises the key findings in this report, where savings estimates are based on 1995-96 data. Table 3G-1: KPMG (1998) Estimates of Cost Savings Possible Through Local Government Amalgamations -

A Dwarf Freshwater Crayfish from the Mary and Brisbane River Drainages, South-Eastern Queensland Robert B

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Nature 56 (2) © Queensland Museum 2013 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 0079-8835 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Director. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site www.qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum The distribution, ecology and conservation status of Euastacus urospinosus Riek, 1956 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Parastacidae), a dwarf freshwater crayfish from the Mary and Brisbane River drainages, south-eastern Queensland Robert B. MCCORMACK Australian Aquatic Biological Pty Ltd, Karuah, NSW 2324. Email: [email protected] Paul VAN DER WERF Earthan Group Pty Ltd, Ipswich, Collinwood Park, Qld 4301 Citation: McCormack, R.B. & Van der Werf, P. 2013 06 30. The distribution, ecology and conservation status of Euastacus urospinosus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Parastacidae), a dwarf freshwater crayfish from the Mary and Brisbane River drainages, south-eastern Queensland. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum — Nature 56(2): 639–646. Brisbane. ISSN 0079–8835. ABSTRACT The Maleny Crayfish Euastacus urospinosus has previously only been recorded from Boo - loumba and Obi Obi Creeks, Mary River, Queensland. -

Fig Parrot Husbandry

Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author AVIAN HUSBANDRY NOTES FIG PARROTS MACLEAY’S FIG PARROT Cyclopsitta diopthalma macleayana BAND SIZE AND SPECIAL BANDING REQUIREMENTS - Band size 3/16” - Donna Corporation Band Bands must be metal as fig parrots are vigorous chewers and will destroy bands made of softer material. SEXING METHODS - Fig Parrots can be sexed visually, when mature (approximately 1 year). Males - Lower cheeks and centre of forehead red; remainder of facial area blue, darker on sides of forehead, paler and more greenish around eyes. Females - General plumage duller and more yellowish than male; centre of forehead red; lower cheeks buff - brown with bluish markings; larger size (Forshaw,1992). ADULT WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS - Male - Wing: 83-90 mm Tail : 34-45 mm Exp. cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g Female - Wing: 79-89 mm Tail: 34-45 mm Exp.cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g (Crome & Shield, 1992) Orange-breasted Fig Parrot Cyclopsitta gulielmitertii Edwards Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris edwardsii Salvadori’s Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris salvadorii Desmarest Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris desmarestii Fig Parrot Husbandry Manual – Draft September2000 Compiled by Liz Romer 1 Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author NATURAL HISTORY Macleay’s Fig Parrot 1.0 DISTRIBUTION Macleay’s Fig Parrot inhabits coastal and contiguous mountain rainforests of north - eastern Queensland, from Mount Amos, near Cooktown, south to Cardwell, and possibly the Seaview Range. This subspecies is particularly common in the Atherton Tableland region and near Cairns where it visits fig trees in and around the town to feed during the breeding season (Forshaw,1992). -

The Status and Impact of the Rainbow Lorikeet (Trichoglossus Haematodus Moluccanus) in South-West Western Australia

Research Library Miscellaneous Publications Research Publications 2005 The status and impact of the Rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus haematodus moluccanus) in south-west Western Australia Tamara Chapman Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/misc_pbns Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Biosecurity Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Ornithology Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, T. (2005), The status and impact of the Rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus haematodus moluccanus) in south-west Western Australia. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia, Perth. Report 04/2005. This report is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Publications at Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Miscellaneous Publications by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 1447-4980 Miscellaneous Publication 04/2005 THE STATUS AND IMPACT OF THE RAINBOW LORIKEET (TRICHOGLOSSUS HAEMATODUS MOLUCCANUS) IN SOUTH-WEST WESTERN AUSTRALIA February 2005 © State of Western Australia, 2005. DISCLAIMER The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Agriculture and the State of Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of negligence or otherwise arising from use or release of this information or any part of it. THE STATUS AND IMPACT OF THE RAINBOW LORIKEET (TRICHOGLOSSUS HAEMATODUS MOLUCCANUS) IN SOUTH-WEST WESTERN AUSTRALIA By Tamra -

Coxen's Fig Parrot Project

A New General Purpose, PC based, Sound Recognition System Neil J Boucher (1), Michihiro Jinnai (2), Ian Gynther (3) (1) Principal Engineer, Compustar, Brisbane, Australia (2) Takamatsu National College of Technology, Japan (3) Conservation Services, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Brisbane, Australia ABSRACT We describe a method of sound recognition, using a novel mathematical approach, which allows precise recognition of a very wide range of different sounds. The mathematical approach is based on the use of the LPC transform to characterize the waveform and the Geometric Distance to compare the resultant pattern with a library of reference patterns of different sounds. The PC hardware consists of a dual processor P4 Pentium computer running at 3.0 GHz or faster. The system can use multiple sound cards and process ten or more sources recording at 44 kbps simultaneously. The initial application for this system is to monitor on a 24/7 basis, the calls of a rare parrot, reporting any detections in real-time by SMS and email. We show recognition capability that is orders of magnitude better than expert human listeners. INTRODUCTION approach to locating this species is required This project is being undertaken in cooperation with the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) of the State of Queensland, Australia. Ian Gynther of the EPA is coordinating the project. The objective is to use computer sound recognition software and the appropriate hardware to monitor sites occupied by the parrot on a 24-hour basis. The computer detects calls in real-time and alerts officials once a target call has been detected. To be able to detect the calls, we needed some indication of how many different types of calls the bird could be expected to make and something of their nature. -

South East Queensland

YOUR FAMILY’S GUIDE TO EXPLORING OUR NATIONAL PARKS SOUTH EAST QUEENSLAND Featuring 78 walks ideal for children Contents A BUSH ADVENTURE A bush adventure with children . 1 Planning tips . 2 WITH CHILDREN As you walk . 4 Sometimes wonderful … As you stop and play . 6 look what can we As you rest, eat and contemplate . 8 This is I found! come again? Great short walks for family outings. 10 awesome! Sometimes more of a challenge … I'm tired/ i need are we hungry/bored the toilet nearly there? Whether the idea of taking your children out into nature fills you with a sense of excited anticipation or nervous dread, one thing is certain – today, more than ever, we are well aware of the benefits of childhood contact with nature: 1. Positive mental health outcomes; 2. Physical health benefits; 3. Enhanced intellectual development; and 4. A stronger sense of concern and care for the environment in later life. Planet Ark – Planting Trees: Just What the Doctor Ordered Above all, it can be fun! But let’s remember … Please don’t let your expectations of what should “If getting our kids out happen as you embark on a bush adventure into nature is a search for prevent you from truly experiencing and perfection, or is one more enjoying what does happen. Simply setting chore, then the belief in the intention to connect your children to a perfection and the chore natural place and discover it alongside defeats the joy.” 2nd Edition - 2017 them is enough. We invite you to enjoy Produced & published by the National Parks Association of Queensland Inc. -

Ficus Rubiginosa 1 (X /2)

KEY TO GROUP 4 Plants with a milky white sap present – latex. Although not all are poisonous, all should be treated with caution, at least initially. (May need to squeeze the broken end of the stem or petiole). The plants in this group belong to the Apocynaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Moraceae, and Sapotaceae. Although an occasional vine in the Convolvulaceae which, has some watery/milky sap will key to here, please refer to Group 3. (3.I, 3.J, 3.K) A. leaves B. leaves C. leaves alternate opposite whorled 1 Leaves alternate on the twigs (see sketch A), usually shrubs and 2 trees, occasionally a woody vine or scrambler go to Group 4.A 1* Leaves opposite (B) or whorled (C), i.e., more than 2 arising at the same level on the twigs go to 2 2 Herbs usually less than 60 cm tall go to Group 4.B 2* Shrubs or trees usually taller than 1 m go to Group 4.C 1 (All Apocynaceae) Ficus obliqua 1 (x /2) Ficus rubiginosa 1 (x /2) 2 GROUP 4.A Leaves alternate, shrubs or trees, occasional vine (chiefly Moraceae, Sapotaceae). Ficus spp. (Moraceae) Ficus, the Latin word for the edible fig. About 9 species have been recorded for the Island. Most, unless cultivated, will be found only in the dry rainforest areas or closed forest, as in Nelly Bay. They are distinguished by the latex which flows from all broken portions; the alternate usually leathery leaves; the prominent stipule (↑) which encloses the terminal bud and the “fig” (↑) or syconia. This fleshy receptacle bears the flowers on the inside; as the seeds mature the receptacle enlarges and often softens (Think of the edible fig!). -

The Birder, No. 255, Spring 2020

e h T The oBfficial mIagaRzine of BDirds SA SEpring 202R 0 No 255 In this Issue Vale Kent Treloar October Campout Linking people with birds What’s happening to in South Australia Adelaide’s trees? A Colourful Pair A Rainbow Lorikeet pair (Photographed by Jeff Groves on River Torrens Linear Park ,June 2020 ) Contents President’s Message ............................................................................................................ 5 Volunteers wanted ................................................................................................................. 6 Vale Kent Treloar ..................................................................................................................... 7 Conservation Sub-Committee Report ............................................................................... 10 What’s happening to Adelaide’s Trees? ............................................................................. 12 Friends of Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary (FAIBS) ............................................. 16 Your help is still needed ...................................................................................................... 17 Bird Watching is Big Business ............................................................................................ 19 Short-tailed Shearwaters in Trouble ................................................................................. 20 Larry’s Birding Trips ............................................................................................................. -

40736 Open Space Strategy 2011 FINAL PROOF.Indd

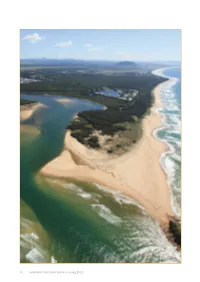

58 Sunshine Coast Open Space Strategy 2011 Appendix 2: Detailed network blueprint The Sunshine Coast covers over 229,072 ha of land. It contains a diverse range of land forms and settings Existing including mountains, rural lands, rivers, lakes, beaches Local recreation park and diverse communities within a range of urban and District recreation park rural settings. Given the size and complexity of the Sunshine Coast open space, the network blueprint Sunshine Coast wide recreation park provides policy guidance for future planning. It addresses existing shortfalls in open space provision as Sports ground well as planning for anticipated requirements responding Amenity reserve to predicted growth of the Sunshine Coast. Environment reserve The network blueprint has been prepared based on three Conservation estate planning catchments to assist readers. Specific purpose sports The three catchments are: Urban Development Area Sunshine Coast wide – recreation parks, sports under ULDA Act 2007 grounds, specific purpose sports and significant Existing signed recreation trails recreation trails that provide a range of diverse and Regional Non-Urban Land Separating unique experiences for users from across the Sunshine Coast from Brisbane to Sunshine Coast. Caboolture Metropolitan Area Community hub District – recreation parks, sports grounds and Locality of Interest recreation trails that provide recreational opportunities boundary at a district level. There are seven open space planning districts, three rural and four urban. Future !( Upgrade local recreation park Local – recreation parks and recreation trails that !( Upgrade Sunshine Coast wide/ provide for the 32 ‘Localities of Interest’ within the district recreation park Sunshine Coast. !( Local recreation park The network blueprint for each catchment provides an (! District recreation park overview of current performance and future directions by category. -

1994 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals

The lUCN Species Survival Commission 1994 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre PADU - MGs COPY DO NOT REMOVE lUCN The World Conservation Union lo-^2^ 1994 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals lUCN WORLD CONSERVATION Tile World Conservation Union species susvival commission monitoring centre WWF i Suftanate of Oman 1NYZ5 TTieWlLDUFE CONSERVATION SOCIET'' PEOPLE'S TRISr BirdLife 9h: KX ENIUNGMEDSPEaES INTERNATIONAL fdreningen Chicago Zoulog k.J SnuicTy lUCN - The World Conservation Union lUCN - The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organisations in a unique world partnership: some 770 members in all, spread across 123 countries. - As a union, I UCN exists to serve its members to represent their views on the world stage and to provide them with the concepts, strategies and technical support they need to achieve their goals. Through its six Commissions, lUCN draws together over 5000 expert volunteers in project teams and action groups. A central secretariat coordinates the lUCN Programme and leads initiatives on the conservation and sustainable use of the world's biological diversity and the management of habitats and natural resources, as well as providing a range of services. The Union has helped many countries to prepare National Conservation Strategies, and demonstrates the application of its knowledge through the field projects it supervises. Operations are increasingly decentralised and are carried forward by an expanding network of regional and country offices, located principally in developing countries. I UCN - The World Conservation Union seeks above all to work with its members to achieve development that is sustainable and that provides a lasting Improvement in the quality of life for people all over the world.