Food Security Stocks and the Wto Legal Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alea Iacta Es: How Spanish Olives Will Force a Radical Change of the CAP Jacques Berthelot ([email protected]), SOL, 7 November 2018

Alea iacta es: how Spanish olives will force a radical change of the CAP Jacques Berthelot ([email protected]), SOL, 7 November 2018 Contents Summary Introduction I – The sequence of the investigation and the arguments put forward by the protagonists 1.1 – The products at issue: processed ripe olives, raw olives or both? 1.2 – The anti-dumping investigation 1.3 – The countervailing (or anti-subsidies) investigation II – Complementary fundamental arguments 2.1 – Why the EU agricultural products are not exported at their "normal value" 2.2 – Almost all EU product-specific agricultural domestic subsidies may be sued under the AoA and ASCM 2.3 – Which subsidies are product-specific (PS)? 2.4 – The case of the EU alleged PS decoupled direct payments 2.4.1 – Spanish ripe olives receive fully decoupled PS subsidies 2.4.2 – Why the other EU agricultural subsidies are not decoupled but are essentially PS 2.4.2.1 – The mixed behaviour of the guardians of the temple of decoupled subsidies 2.4.2.2 – The EU mantra that decoupled subsidies imply a market orientation of the CAP 2.4.2.3 – The reasons why the EU agricultural subsidies are not decoupled but mainly PS 2.4.2.4 – The case of input subsidies 2.4.3 – The WTO Appellate Body has departed from the GATT definition of dumping 2.4.4 – The best rebuttals of the assertion that the EU subsidies are decoupled NPS III – The consequences to draw to delete dumping and to build a totally new CAP 3.1 – Deleting the dumping impact of EU exports, particularly to developing countries 3.1.1 – Changing -

Subsidies on Upland Cotton

United States – Subsidies on Upland Cotton (WT/DS267) Executive Summary of the Rebuttal Submission of the United States of America September 1, 2003 Introduction and Overview 1. The comparison under the Peace Clause proviso in Article 13(b)(ii) must be made with respect to the support as “decided” by those measures. In the case of the challenged U.S. measures, the support was decided in terms of a rate, not an amount of budgetary outlay. The rate of support decided during marketing year 1992 was 72.9 cents per pound of upland cotton; the rate of support granted for the 1999-2001 crops was only 51.92 cents per pound; and the rate of support that measures grant for the 2002 crop is only 52 cents per pound. Thus, in no marketing year from 1999 through 2002 have U.S. measures breached the Peace Clause.1 2. Brazil has claimed that additional “decisions” by the United States during the 1992 marketing year to impose a 10 percent acreage reduction program and 15 percent “normal flex acres” reduced the level of support below 72.9 cents per pound. However, the 72.9 cents per pound rate of support most accurately expresses the revenue ensured by the United States to upland cotton producers. Even on the unrealistic assumption that these program elements reduced the level of support by 10 and 15 percent, respectively (that is, the maximum theoretical effect these program elements could have had), the 1992 rate of support would still be 67.625 cents per pound, well above the levels for marketing years 1999-2001 and 2002. -

Moftic WTO Monitor

This issue of The WTO Monitor focuses on issues of specific interest to small 1 The developing countries such as those in CARICOM. Would There Be War After Nine Years of Peace The ‘Due Restraint’ proviso, more commonly referred to as the ‘Peace Clause’, W contained in Article 13 of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), shields countries granting subsidies which conform with the conditions specified in the T Agreement from being challenged under other WTO agreements, particularly Articles 6.3(a)-(c) and 6.4 of the Subsidies and Countervailing Measure (SCM) Agreement and O related provisions. This Clause expired at the end of 2003, however there appears to be disagreement with regard to the exact expiration date. According to Article 13, this moratorium is supposed to last for the duration of the implementation period of the AoA. Implementation period in this context, according to Article 1 of the AoA which M deals with definitions, means “the six-year period commencing in the year 1995, except that, for the purpose of Article 13, it means the nine-year period commencing in 1995.” For the majority of WTO Member States, as well as senior officials of the O Secretariat (Dr Supachai), the nine-year period expired at the end of 2003. Of late, however, another interpretation as regards the actual expiration date of the Peace N Clause was advanced by the US and the EU, which sees expiration at sometime in 2004. I Although the deadline has elapsed, Members are still expected to decide whether or not to support an extension of the Peace Clause. -

Subsidies on Upland Cotton (WT/DS267)

United States – Subsidies on Upland Cotton (WT/DS267) Comments of the United States of America on the Comments by Brazil and the Third Parties on the Question Posed by the Panel I. Overview 1. The United States thanks the Panel for this opportunity to provide its views on the comments by Brazil and the third parties on the question concerning Article 13 of the Agreement on Agriculture (“Agriculture Agreement”) posed by the Panel in its fax of May 28, 2003.1 The interpretation of Article 13 (the “Peace Clause”) advanced by Brazil and endorsed by some of the third parties is deeply flawed. Simply put, Brazil fails to read the Peace Clause according to the customary rules of interpretation of public international law. Its interpretation does not read the terms of the Peace Clause according to their ordinary meaning, ignores relevant context, and would lead to an absurd result. 2. Brazil reads the Peace Clause phrase “exempt from actions” to mean only that “a complaining Member cannot receive authorization from the DSB [Dispute Settlement Body] to obtain a remedy against another Member’s domestic and export support measures that otherwise would be subject to the disciplines of certain provisions of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures . or Article XVI of GATT 1994.’”2 However, Brazil’s reading simply ignores parts of the definition of “actions” that it quotes: “The dictionary definition of ‘actions’ is ‘the taking of legal steps to establish a claim or obtain a remedy.”3 Thus, while the United States would agree that the phrase “exempt from actions” precludes “the taking of legal steps to . -

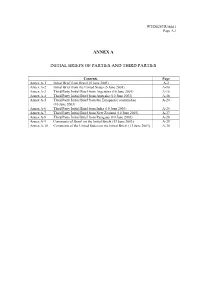

Annex a Initial Briefs of Parties and Third Parties

WT/DS267/R/Add.1 Page A-1 ANNEX A INITIAL BRIEFS OF PARTIES AND THIRD PARTIES Contents Page Annex A-1 Initial Brief from Brazil (5 June 2003) A-2 Annex A-2 Initial Brief from the United States (5 June 2003) A-10 Annex A-3 Third Party Initial Brief from Argentina (10 June 2003) A-15 Annex A-4 Third Party Initial Brief from Australia (10 June 2003) A-18 Annex A-5 Third Party Initial Brief from the European Communities A-20 (10 June 2003) Annex A-6 Third Party Initial Brief from India (10 June 2003) A-25 Annex A-7 Third Party Initial Brief from New Zealand (10 June 2003) A-27 Annex A-8 Third Party Initial Brief from Paraguay (10 June 2003) A-28 Annex A-9 Comments of Brazil on the Initial Briefs (13 June 2003) A-29 Annex A-10 Comments of the United States on the Initial Briefs (13 June 2003) A-38 WT/DS267/R/Add.1 Page A-2 ANNEX A-1 BRAZIL’S BRIEF ON PRELIMINARY ISSUE REGARDING THE “PEACE CLAUSE” OF THE AGREEMENT ON AGRICULTURE 5 June 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY ............................................................................... 2 II. ANALYSIS OF THE PHRASE "EXEMPT FROM ACTIONS" ................................... 3 III. THE CONTEXT OFF ARTICLE 13 DEMONSTRATES THAT THERE IS NO LEGAL REQUIREMENT FOR THE PANEL TO FIRST MAKE A FINDING ON THE PEACE CLAUSE BEFORE PERMITTING BRAZIL TO SET OUT ITS ARGUMENT AND CLAIMS REGARDING US VIOLATIONS OF THE SCM AGREEMENT ................................................................................................. 5 IV. RESOLUTION OF THRESHOLD ISSUES PRIOR TO PROVIDING PARTIES THE OPPORTUNITY TO PRESENT ALL OF ITS EVIDENCE IS CONTRARY TO THE PRACTICE OF EARLIER PANELS .................................. -

Foreign Trade Remedy Investigations of U.S

Foreign Trade Remedy Investigations of U.S. Agricultural Products Updated November 10, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46263 SUMMARY R46263 Foreign Trade Remedy Investigations of November 10, 2020 U.S. Agricultural Products Anita Regmi Foreign countries appear to be making greater use of punitive measures affecting U.S. Specialist in Agricultural agricultural exports. These measures, corresponding to duties the United States has long imposed Policy on imports found to be traded unfairly and injuring U.S. industries, have the potential to reduce the competitiveness of U.S. agricultural exports in some foreign markets. Recent changes in U.S. Nina M. Hart agricultural policy, including several large ad hoc domestic spending programs—valued at up to Legislative Attorney $60.4 billion—in response to international trade retaliation in 2018 and 2019, and to economic disruption caused by the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020, may increase the likelihood of foreign measures that adversely affect U.S. agricultural trade. Randy Schnepf Specialist in Agricultural The imposition of anti-dumping and countervailing duties is governed by the rules of the World Policy Trade Organization (WTO) and of WTO’s 1995 Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). Under the AoA, member countries agreed to reform their domestic agricultural support policies, increase access to imports, and reduce export subsidies. The AoA spells out the rules to determine whether policies are potentially trade distorting. If a trading partner believes that imported agricultural products are sold below cost (“dumped”) or benefit from unfair subsidies, it may impose anti-dumping (AD) or countervailing duties (CVD) on those imports to eliminate the unfair price advantage. -

Legal Options for a Sustainable Energy Trade Agreement

Legal Options for a Sustainable Energy Trade Agreement July 2012 ICTSD Global Platform on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainable Energy Matthew Kennedy University of International Business and Economics, Beijing A joint initiative with Legal Options for a Sustainable Energy Trade Agreement ICTSD July 2012 ICTSD Global Platform on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainable Energy Matthew Kennedy University of International Business and Economics, Beijing i Published by International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) International Environment House 2 7 Chemin de Balexert, 1219 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 917 8492 Fax: +41 22 917 8093 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.ictsd.org Publisher and Director: Ricardo Meléndez-Ortiz Programme Manager: Ingrid Jegou Programme Officer: Mahesh Sugathan Acknowledgments This paper is produced by the Global Platform on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainable Energy of the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD). The concept of the research has been informed by ICTSD policy dialogues during the past year, in particular a dialogue organized in Washington DC in November 2011 by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) with support of the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) and ICTSD as well as a high-level Roundtable in Geneva organized in December 2011 on the occasion of the Eighth Ministerial Conference of the WTO. The author thanks Ricardo Meléndez-Ortiz, Ingrid Jegou, Mahesh Sugathan, Marie Wilke and Joachim Monkelbaan from ICTSD for their guidance and inputs during the production of the paper. The author is also grateful for the comments on an earlier draft received from Prof. Thomas Cottier, Prof. -

Annex C Oral Statements of Parties and Third Parties At

WT/DS267/R/Add.1 Page C-1 ANNEX C ORAL STATEMENTS OF PARTIES AND THIRD PARTIES AT THE FIRST SESSION OF THE FIRST SUBSTANTIVE MEETING Contents Page Annex C-1 Executive Summary of the Opening Statement of Brazil C-2 Annex C-2 Executive Summary of the Closing Statement of Brazil C-7 Annex C-3 Executive Summary of the Opening Statement of the United States C-12 Annex C-4 Executive Summary of the Closing Statement of the United States C-16 Annex C-5 Third Party Oral Statement of Argentina C-20 Annex C-6 Third Party Oral Statement of Australia C-27 Annex C-7 Third Party Oral Statement of Benin C-33 Annex C-8 Third Party Oral Statement of Canada C-36 Annex C-9 Third Party Oral Statement of China C-40 Annex C-10 Third Party Oral Statement of the European Communities C-43 Annex C-11 Third Party Oral Statement of India C-53 Annex C-12 Third Party Oral Statement of New Zealand C-55 Annex C-13 Third Party Oral Statement of Paraguay C-58 Annex C-14 Third Party Oral Statement of Chinese Taipei C-61 WT/DS267/R/Add.1 Page C-2 ANNEX C-1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ORAL STATEMENT OF BRAZIL AT THE FIRST SUBSTANTIVE MEETING OF THE PANEL WITH THE PARTIES I. INTRODUCTION 1. Brazil addresses first various peace clause issues, followed by Step 2 export and domestic payments, export credit guarantees and the ETI Act subsidies. Finally, Brazil addresses the “preliminary issues” raised by the United States. -

U.S. Farm Subsidies and the Expiration of the Wto's Peace Clause

U.S. FARM SUBSIDIES AND THE EXPIRATION OF THE WTO'S PEACE CLAUSE MATTHEW C. PORTERFIELD* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. IN TRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1002 2. SUBSIDIES PROGRAMS UNDER THE FARM BILL ........................ 1004 2.1. Pre-1996 Farm Subsidy Programs ................................... 1004 2.2. The 1996 Farm Bill ........................................................... 1005 2.3. The 2002 Farm Bill ........................................................... 1006 3. THE PRINCIPLE WTO AGREEMENTS APPLICABLE TO FARM SUBSIDIES: THE AGREEMENT ON AGRICULTURE AND THE AGREEMENT ON SUBSIDIES AND COUNTERVAILING MEASURES ........................ 1007 3.1. The Agreement on Agriculture ......................................... 1008 3.2. The Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures ........................................................................... 1013 4. THE UNITED STATES' STRATEGY FOR PROTECTING FARM SUBSIDIES IN THE DOHA ROUND OF WTO NEGOTIATIONS ... 1024 4.1. The B lue B ox ..................................................................... 1026 4.2. The G reen Box ................................................................... 1028 4.3. The Amber Box and Total Trade-DistortingSupport ...... 1030 4.4. The Peace Clause............................................................... 1033 5. GUIDELINES FOR DRAFTING A WTO-COMPLIANT FARM BILL THAT MAINTAINS THE CURRENT BASELINE ............................ 1034 5.1. Eliminate or Limit Price-ContingentPrograms .............. -

Foreign Trade Remedy Investigations of U.S. Agricultural Products

Foreign Trade Remedy Investigations of U.S. Agricultural Products March 11, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46263 SUMMARY R46263 Foreign Trade Remedy Investigations of U.S. March 11, 2020 Agricultural Products Anita Regmi Foreign countries appear to be making greater use of punitive measures affecting U.S. Analyst in Agricultural agricultural exports. These measures, corresponding to duties the United States has long Policy imposed on imports found to be traded unfairly and injuring U.S. industries, have the potential to reduce the competitiveness of U.S. agricultural exports in some foreign Nina M. Hart markets. Recent changes in U.S. agricultural policy, including over $23 billion in “trade Legislative Attorney aid” payments in 2018 and 2019 to farmers affected by higher Chinese tariffs on certain U.S. products, may increase the likelihood of foreign measures that adversely affect U.S. Randy Schnepf agricultural trade. Specialist in Agricultural Policy The imposition of anti-dumping and countervailing duties is governed by the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and of WTO’s 1995 Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). Under the AoA, member countries agreed to reform their domestic agricultural support policies, increase access to imports, and reduce export subsidies. The AoA spells out the rules to determine whether policies are potentially trade distorting. If a trading partner believes that imported agricultural products are being sold below cost (“dumped”) or benefit from unfair subsidies, it may impose anti-dumping (AD) or countervailing duties (CVD) on those imports to eliminate the unfair price advantage. In recent years, a number of trading partners have challenged imports of U.S. -

The Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture: an Evaluation

6JG7TWIWC[4QWPF#ITGGOGPVQP #ITKEWNVWTG#P'XCNWCVKQP %QOOKUUKQPGF2CRGT0WODGT 6JG +PVGTPCVKQPCN #ITKEWNVWTCN 6TCFG 4GUGCTEJ %QPUQTVKWO $TKPIKPI#ITKEWNVWTGKPVQVJG)#66 6JG7TWIWC[4QWPF#ITGGOGPVQP #ITKEWNVWTG#P'XCNWCVKQP The International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium Commissioned Paper Number 9 July 1994 IATRC Commissioned Paper No. 9 The Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture: An Evaluation This Commissioned Paper was co-authored by a working group, organized by the IATRC. The members of the working group were: Tim Josling (Chair) Bill Miner Food Research Institute Centre for Trade Policy and Law Stanford University Ottawa, Canada Masayoshi Honma Dan Sumner Economics Department Department of Agricultural Economics Otaru University of Commerc University of California, Davis Jaeok Lee Stefan Tangermann Korean Rural Economic Institute Institute of Agricultural Economics Seoul, Korea University of Gottingen Donald MacLaren Alberto Valdes Department of Agriculture The World Bank University of Melbourne Washington, D.C. All authors participated as private individuals, and the views expressed should not be taken to represent those of institutions to which they are attached. The International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium is an informal association of university and government economists interested in agricultural trade. For further information please contact Professor Alex McCalla, Chairman, IATRC, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of California at Davis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . ....... .i Executive Summary . .......iii -

UNREVISED PROOF COPY Ev 3 HOUSE of LORDS MINUTES OF

UNREVISED PROOF COPY Ev 3 HOUSE OF LORDS MINUTES OF EVIDENCE TAKEN BEFORE THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE EUROPEAN UNION (SUB-COMMITTEE A) INQUIRY INTO THE WTO: THE ROLE OF THE EU POST-CANCÚN TUESDAY 27 JANUARY 2004 MR JONATHAN PEEL, MS RUTH RAWLING MR MICHAEL PASKE and MR MARTIN HAWORTH Evidence heard in Public Questions 64 - 105 USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT 1. This is an uncorrected and unpublished transcript of evidence taken in public and reported to the House. 2. The transcript is not yet an approved formal record of these proceedings. Any public use of, or reference to, the contents should make clear that neither Members nor witnesses have had the opportunity to correct the record. If in doubt as to the propriety of using the transcript, please contact the Clerk to the Committee. 3. Members who receive this for the purpose of correcting questions addressed by them to witnesses are asked to send corrections to the Clerk to the Committee. 4. Prospective witnesses may receive this in preparation for any written or oral evidence they may in due course give to the Committee. TUESDAY 27 JANUARY 2004 ________________ Present Cobbold, L Hannay of Chiswick, L Jones, L Jordan, L Marlesford, L Radice, L (Chairman) Taverne, L ________________ Witnesses: Mr Jonathan Peel, Director, EU and International Policy, and Ms Ruth Rawling, Cargill plc, Vice Chair, Trade Policy and CAP Committee, Food and Drink Federation, and; Mr Michael Paske, Vice President, and Mr Martin Haworth, Director of Policy, National Farmers’ Union, examined. Q64 Chairman: Welcome. Would anybody like to introduce your team? Mr Paske: I would be happy to introduce my team, my Lord Chairman.