Snail Bullhead Ameiurus Brunneus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico And

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes THIRD EDITION GSMFC No. 300 NOVEMBER 2020 i Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Commissioners and Proxies ALABAMA Senator R.L. “Bret” Allain, II Chris Blankenship, Commissioner State Senator District 21 Alabama Department of Conservation Franklin, Louisiana and Natural Resources John Roussel Montgomery, Alabama Zachary, Louisiana Representative Chris Pringle Mobile, Alabama MISSISSIPPI Chris Nelson Joe Spraggins, Executive Director Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc. Mississippi Department of Marine Bon Secour, Alabama Resources Biloxi, Mississippi FLORIDA Read Hendon Eric Sutton, Executive Director USM/Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Florida Fish and Wildlife Ocean Springs, Mississippi Conservation Commission Tallahassee, Florida TEXAS Representative Jay Trumbull Carter Smith, Executive Director Tallahassee, Florida Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas LOUISIANA Doug Boyd Jack Montoucet, Secretary Boerne, Texas Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Baton Rouge, Louisiana GSMFC Staff ASMFC Staff Mr. David M. Donaldson Mr. Bob Beal Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Steven J. VanderKooy Mr. Jeffrey Kipp IJF Program Coordinator Stock Assessment Scientist Ms. Debora McIntyre Dr. Kristen Anstead IJF Staff Assistant Fisheries Scientist ii A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes Third Edition Edited by Steve VanderKooy Jessica Carroll Scott Elzey Jessica Gilmore Jeffrey Kipp Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission 2404 Government St Ocean Springs, MS 39564 and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission 1050 N. Highland Street Suite 200 A-N Arlington, VA 22201 Publication Number 300 November 2020 A publication of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Number NA15NMF4070076 and NA15NMF4720399. -

United States National Museum Bulletin 282

Cl>lAat;i<,<:>';i^;}Oit3Cl <a f^.S^ iVi^ 5' i ''*«0£Mi»«33'**^ SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION MUSEUM O F NATURAL HISTORY I NotUTus albater, new species, a female paratype, 63 mm. in standard length; UMMZ 102781, Missouri. (Courtesy Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan.) UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 282 A Revision of the Catfish Genus Noturus Rafinesque^ With an Analysis of Higher Groups in the Ictaluridae WILLIAM RALPH TAYLOR Associate Curator, Division of Fishes SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS CITY OF WASHINGTON 1969 IV Publications of the United States National Museum The scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States National Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin. In these series are published original articles and monographs dealing with the collections and work of the Museum and setting forth newly acquired facts in the fields of anthropology, biology, geology, history, and technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries and scientific organizations and to specialists and others interested in the various subjects. The Proceedings, begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume. In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902, papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herbarium. -

Variable Growth and Longevity of Yellow Bullhead (Ameiurus Natalis) in the Everglades of South Florida, USA by D

Journal of Applied Ichthyology J. Appl. Ichthyol. 25 (2009), 740–745 Received: August 12, 2008 Ó 2009 The Authors Accepted: February 20, 2009 Journal compilation Ó 2009 Blackwell Verlag GmbH doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0426.2009.01300.x ISSN 0175–8659 Variable growth and longevity of yellow bullhead (Ameiurus natalis) in the Everglades of south Florida, USA By D. J. Murie1, D. C. Parkyn1, W. F. Loftus2 and L. G. Nico3 1Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Forest Resources and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA; 2U.S. Geological Survey, Florida Integrated Science Center, Everglades National Park Field Station, Homestead, FL, USA; 3U.S. Geological Survey, Florida Integrated Science Center, Gainesville, FL, USA Summary bullhead is the most abundant ictalurid catfish in the Yellow bullhead (Ictaluridae: Ameiurus natalis) is the most Everglades (Loftus and Kushlan, 1987; Nelson and Loftus, abundant ictalurid catfish in the Everglades of southern 1996), there is no information on the age and growth for the Florida, USA, and, as both prey and predator, is one of many species in southern Florida. This lack of information severely essential components in the ecological-simulation models used limits the ability of management agencies to predict effects on in assessing restoration success in the Everglades. Little is the population dynamics or resiliency of yellow bullhead known of its biology and life history in this southernmost populations in relation to changes in environmental conditions portion of its native range; the present study provides the first with altered hydrology. estimates of age and growth from the Everglades. In total, 144 The aim of the present study was to describe and model the yellow bullheads of 97–312 mm total length (TL) were age and growth of yellow bullhead from the Everglades. -

Black Bullhead BISON No.: 010065

Scientific Name: Ameiurus melas Common Name: Black bullhead BISON No.: 010065 Legal Status: ¾ Arizona, Species of ¾ ESA, Proposed ¾ New Mexico-WCA, Special Concern Threatened Threatened ¾ ESA, Endangered ¾ ESA, Threatened ¾ USFS-Region 3, ¾ ESA, Proposed ¾ New Mexico-WCA, Sensitive Endangered Endangered ¾ None Distribution: ¾ Endemic to Arizona ¾ Southern Limit of Range ¾ Endemic to Arizona and ¾ Western Limit of Range New Mexico ¾ Eastern Limit of Range ¾ Endemic to New Mexico ¾ Very Local ¾ Not Restricted to Arizona or New Mexico ¾ Northern Limit of Range Major River Drainages: ¾ Dry Cimmaron River ¾ Rio Yaqui Basin ¾ Canadian River ¾ Wilcox Playa ¾ Southern High Plains ¾ Rio Magdalena Basin ¾ Pecos River ¾ Rio Sonoita Basin ¾ Estancia Basin ¾ Little Colorado River ¾ Tularosa Basin ¾ Mainstream Colorado River ¾ Salt Basin ¾ Virgin River Basin ¾ Rio Grande ¾ Hualapai Lake ¾ Rio Mimbres ¾ Bill Williams Basin ¾ Zuni River ¾ Gila River Status/Trends/Threats (narrative): State NM: Provides full protection. Distribution (narrative): Black bullheads are found from southern Ontario, Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River, south to the Gulf of Mexico and northern Mexico, and from Montana to Appalachians (Lee et. al. 1981). The black bullhead is native only to the Canadian drainage and possibly the Pecos. The black bullhead has been introduced all other major drainages of New Mexico except the Tularosa basin (Sublette et. al. 1990). Key Distribution/Abundance/Management Areas: Panel key distribution/abundance/management areas: Breeding (narrative): Age of maturity is variable but is attained from the second to fourth summer, depending on population density (Becker 1983). Spawning occurs in spring and early summer at water temperatures above 20 C in shallow water over a variety of substrates (Stuber 1982). -

Proposed Expansion San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge San Joaquin, Stanislaus, and Merced Counties, California

Appendix D Species Found on the San Joaquin River NWR, or Within the Proposed Expansion Area Proposed Expansion San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge San Joaquin, Stanislaus, and Merced Counties, California United States Department of the Interior U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service This page intentionally left blank Appendix D: Species List Species Found on the San Joaquin River NWR, or within the Proposed Expansion Area Invertebrates Artemia franciscana brine shrimp Branchinecta coloradensis Colorado fairy shrimp Branchinecta conservatio Conservancy fairy shrimp (FE) Branchinecta lindahli (no common name) Branchinecta longiantenna longhorn fairy shrimp (FE) Branchinecta lynchi vernal pool fairy shrimp (FT) Branchinecta mackini (no common name) Branchinecta mesovallensis midvalley fairy shrimp Lepidurus packardi vernal pool tadpole shrimp (FE) Linderiella occidentalis California linderiella Anticus antiochensis Antioch Dunes anthicid beetle (CS) Anticus sacramento Sacramento anthicid beetle (CS) Desmocerus californicus dimorphus Valley elderberry longhorn beetle (FT) Hygrotus curvipes curved-foot hygrotus diving beetle (CS) Lytta moesta moestan blister beetle (CS) Lytta molesta molestan blister beetle (CS) Vertebrates Amphibia Caudata: Ambystomatidae Ambystoma californiense California tiger salamander (CP, CS) Anura: Pelobatidae Spea hammondii western spadefoot (CP, CS) Bufonidae Bufo boreas western toad Hylidae Hyla regilla Pacific treefrog Ranidae Rana aurora red-legged frog (FT, CP, CS) Rana boylii foothill yellow-legged frog (CP, CS, -

![Catfish Management Plan [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8759/catfish-management-plan-pdf-2878759.webp)

Catfish Management Plan [PDF]

Distribution, Biology, and Management of Wisconsin’s Ictalurids Statewide catfish management plan April 2016 INTRODUCTION Wisconsin's Ictalurids can be classed into three broad groups. The bullheads – yellow, brown and black – are closely related members of the genus Ameiurus. The madtoms – slender, tadpole and stonecat – all belong to the genus Noturus. The two large catfish – the channel catfish and flathead catfish – are not closely related, but are linked by their importance as recreational and commercial species. Ictalurids are found in all three of Wisconsin's major drainages – the Mississippi River, Lake Michigan, and Lake Superior. Wisconsin has over 3,000 river miles of catfish water, along with several lakes and reservoirs that also support populations. They are most common in the Mississippi River and in the southern parts of the state. Although Wisconsin’s Ictalurids, such as channel catfish, do not enjoy the widespread glamour and status that they do in the southern United States, they are becoming more popular with Wisconsin’s anglers. A 2006-2007 mail survey revealed nearly 800,000 channel catfish were caught, while the harvest rate was nearly 70%. This harvest rate was highest among fish species targeted by Wisconsin anglers. Channel catfish are also an important commercial fishery on the Mississippi River, while setline anglers are active in many rivers of the state. As for flathead catfish, anecdotal evidence suggests that Wisconsin’s largest predatory fish is becoming a highly sought after trophy specimen. Given anglers’ increased propensity to fish for a food source as well as to fish for trophies, channel catfish and flathead catfish do not appear to have peaked in popularity. -

Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater And

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Cross-Species Evaluation of Molecular Target Sequence and Structural

Cross-species Evaluation of Molecular Target Sequence and Structural Conservation as a Line of Evidence for Identification of Susceptible Taxa to Inform ToxicityTesting Carlie A. LaLone, Ph.D. Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Outline • Aquatic Life Criteria – Required data • New tool to inform criteria: Sequence Alignment to Predict Across Species Susceptibility • Demonstrate Application – Existing Criteria – Emerging chemicals Current Data Requirements Data from a Prescribed List of Species Freshwater Species Saltwater Species Acute Tests: Acute Tests: • Salmonidae • 2 species from phylum Chordata • Rec/Comm important warm-water fish • Phylum not Arthropoda or Chordata • Other vertebrate • Mysidae or Penaeidae family • Planktonic crustacean • 3 families not Chordata or used above • Benthic crustacean • Any other family • Insect • Phylum not Arthropoda or Chordata • Another phylum or insect Chronic Tests: Life-cycle, Partial life-cycle, Chronic Tests: Life-cycle, Partial life-cycle, Early life-stage Early life-stage • Fish • Fish • Invertebrate • Invertebrate • Sensitive fresh water • Sensitive saltwater species Key Questions for Deriving Criteria • Does data exist to develop criteria? – If data gaps exist are they necessary/unnecessary to fill? • If data available for some species are they representative of others needing protection? • With emerging chemicals, such as pharmaceuticals, limited if any toxicity data exists across taxa – What data would be necessary for deriving criteria? Proposed use -

Prevalence of Tumors in Brown Bullhead from Three Lakes in Southeastern Massachusetts, 2002

Baumann and others— Toxic Substances Hydrology Program Fisheries: Aquatic and Endangered Resources Program Contaminant Biology Program Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Prevalence of Tumors in Brown Bullhead from Three Lakes Southeastern Massachusetts Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Prevalence of Tumors in Brown Bullhead from Three Lakes in Southeastern Massachusetts, 2002 —Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5198 Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5198 U.S. Department of the Interior Printed on recycled paper U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Photographs (clockwise from top left) showing (A) deployment of a fyke net in Ashumet Pond, (B) oral lesions in brown bullhead, (C) side view of brown bullhead as its length is being measured, and (D) front view of brown bullhead. Prevalence of Tumors in Brown Bullhead from Three Lakes in Southeastern Massachusetts, 2002 By Paul C. Baumann1, Denis R. LeBlanc1, Vicki S. Blazer1, John R. Meier3, Stephen T. Hurley2, and Yasu Kiryu1 1 U.S. Geological Survey 2 Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts 3 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Cincinnati, Ohio Toxic Substances Hydrology Program Fisheries: Aquatic and Endangered Resources Program Contaminant Biology Program Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5198 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

When Did the Black Bullhead, Ameiurus Melas (Teleostei: Ictaluridae), Arrive in Poland?

Arch. Pol. Fish. (2010) 18: 183-186 DOI 10.2478/v10086-010-0021-0 SHORT COMMUNICATION When did the black bullhead, Ameiurus melas (Teleostei: Ictaluridae), arrive in Poland? Received – 25 May 2010/Accepted – 01 June 2010. Published online: 30 September 2010; ©Inland Fisheries Institute in Olsztyn, Poland Micha³ Nowak, Ján Košèo, Pawe³ Szczerbik, Dominika Mierzwa, W³odzimierz Popek Abstract. One specimen of the non-native ictalurid catfish the Many years ago it was established that the brown black bullhead, Ameiurus melas, was found in the collection bullhead, Ameiurus nebulosus (Lesueur), was the of the Museum and Institute of Zoology of the Polish Academy only ictalurid species introduced into Polish waters of Sciences in Warsaw, Poland. This finding strongly supports from North America (Horoszewicz 1971, Witkowski the hypothesis that the black bullhead was co-introduced into Polish waters with the brown bullhead, Ameiurus nebulosus, 2002). However, in 2007 another catfish from the at the end of the nineteenth century. The species might be family Ictaluridae – the black bullhead, Ameiurus distributed widely throughout Poland, thus careful melas (Rafinesque) – was recorded in the Szyd³ówek investigation on the identity of the ictalurid catfish population Dam Reservoir in Kielce, Œwiêtokrzyskie District throughout the country should be carried out. (Nowak et al. 2010). Ten specimens were obtained from recreational fishers in summer 2007, and the Keywords: alien fish, Ictaluridae, introduction, invasive species, xenodiversity species has been noted consistently in subsequent years (Nowak, unpubl.). These observations permit the supposition that the black bullhead has estab- lished a self-sustaining population in this reservoir. Presumably, the occurrence of A. -

Noturus Eleutherus)

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2017 Aspects of the Physiological and Behavioral Defense Adaptations of the Mountain Madtom (Noturus eleutherus) Meredith Leigh Hayes University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Hayes, Meredith Leigh, "Aspects of the Physiological and Behavioral Defense Adaptations of the Mountain Madtom (Noturus eleutherus). " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4968 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Meredith Leigh Hayes entitled "Aspects of the Physiological and Behavioral Defense Adaptations of the Mountain Madtom (Noturus eleutherus)." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. J. Brian Alford, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Gerald Dinkins, Jeffrey Becker, J. R. Shute Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Aspects of the Physiological and Behavioral Defense Adaptations of the Mountain Madtom (Noturus eleutherus) A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Meredith Leigh Hayes December 2017 ii Copyright ã by Meredith Hayes Harris All rights reserved. -

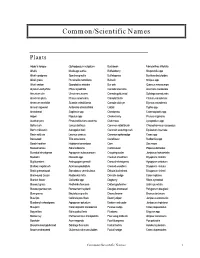

Common/Scientific Names

Common/Scientific Names Plants Adder's tongue Ophioglossum vulgatum Buckbean Menyanthes trifoliata Alfalfa Medicago sativa Buffaloberry Shepherdia spp Alkali cordgrass Spartina gracilis Buffalograss Buchloe dactyloides Alkali grass Puccinellia nuttaliana Bulrush Scirpus spp Alkali sacton Sporobolus airoides Bur oak Quercus macrocarpa Alyssum-leaf phlox Phlox alyssifolia Canada anemone Anemone candensis American elm Ulmus americana Canada goldenrod Solidago canadensis American plum Prunus americana Canada thistle Cirsium canadensis American sea blite Suaeda caleoliformis Canada wild rye Elymus canadensis Annual ragweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia Cattail Typha spp Arrowhead Sagittaria spp Cheatgrass Calamagrostis spp Aspen Populus spp Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Austrian pine Pinus balfouriana austrina Club moss Lycopodium spp Baltic rush Juncus balticus Common rabbitbrush Chrysothamnus nauseosus Barr’s milkvetch Astragalus barii Common scouring rush Equisetum hyemale Basin wild rye Leymus cinerus Common spikesedge Carex spp Basswood Tilia americana Coneflower Rudbeckia spp Beach heather Hudsonia tomentosa Corn Zea mays Beaked willow Salix bebbiana Cottonwood Populus deltoides Bearded wheatgrass Agropyron subsecundum Creeping cedar Juniperus horizontalis Beebalm Monarda spp Crested shield fern Dryopteris cristata Big bluestem Andropogon gerardii Crested wheatgrass Agropyron cristatum Birdfoot sagebrush Artemisia pedatifida Crested woodfern Dryopteris cristata Black greasewood Sarcobatus vermiculatus Dakota buckwheat Eriogonum visheri Black-eyed