Project in Lesotho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Appeal Operation Update Lesotho: Food Insecurity

Emergency appeal operation update Lesotho: Food Insecurity Emergency Appeal n° MDRLS004 Glide n° OT-2016-000005-LSO Date of Issue: 19 July 2016 Expected end date: 31 July 2016 New end date: 31 December 2016 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact: Prof Teboho Kitleli, Secretary General of Lesotho Red Cross Hung Ha Nguyen, Disaster Preparedness Delegate, IFRC, Southern Africa Operation start date: 22 January 2016 Expected timeframe: 6 months New timeframe: 11 months Appeal budget: CHF 735,735 Total number of people affected: 180,000 Number of people to be assisted: 9,000 individuals (1,800HH) Host National Society presence: Lesotho Red Cross Society, 9 staff members and 30 volunteers actively engage in emergency response in three districts of Qacha’s Nek, Thaba Tseka, and Mafeteng. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: IFRC (Southern Africa Country Cluster Office), Monaco Red Cross, the Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross and British Red Cross Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Government of Lesotho (GoL) through the Disaster Management Authority is coordinating responses at country level. The UN-WFP plans to launch an appeal and will collaborate with government and other humanitarian partners. This Operations Update aims to provide the intervention progress up to date and request for a 5 months’ extension to complete the outstanding activities and call for additional contributions to further fulfil emerging needs from affected people and communities. Appeal History: This Emergency Appeal was launched on 22 January 2016 for CHF 669,160 Swiss francs to enable the IFRC to support the Lesotho Red Cross Society (LRCS) to respond to the food security needs of 4,500 drought affected beneficiaries for six months. -

Mohale's Hoek District Council

MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL Information Handbook 2009 Handbook MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL GOVERNMENT DISTRICT INFORMATION HANDBOOK June 2009 A COMPILATION OF CRUCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE DISTRICT (DISAGGREGATED COUNCIL-WISE) Ministry of local Government and Chieftainship German Technical Cooperation Department of Planning Kingdom of Lesotho Information Handbook 2009 1 handbook contents Prepared by: Department of Planning, Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………….............. 04 Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Mohale’s Hoek District Map………………………………………………………................. 05 Supported by: GTZ Lesotho Introduction………………………………………………………………………...........…….. 06 Background to Local Government in Lesotho……………………………............…………. 07 The Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Methodology…………………………………………………………………...........…………. 08 (MOLGC) through its Department of Planning, remains the owner of this handbook. However, there shall be no copy- 1. Profile of Community Councils……………………………………...……………… 09 right restrictions over the use or replication of the whole 2. Social Indicators……………………………………………………...……………… 10 or parts of this handbook. This is an approach for utiliza- 3. Gender Aspects……………………………………………………....………………. 11 tion by the interested parties and is entirely in the public domain. However, no changes shall be made 4. Agriculture………………………………………………………….………………… 12 to the handbook and reprinted thus without prior 5. Trade and Commerce…………………………………………………...…………… 13 permission of MOLGC. 6. Health…………………………………………………………………….…………… -

( 14 Zdthd" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> "TV D>( 14 Zdthd

( l ? 1 ) 0 MAFETENG TOWN : ITS ECONOMIC STRUCTURE AND REGIONAL FUNCTIONS INSTITUTE OPj£ 1 1 APR 1934 ■ MVtlOmiOT STUDIES U G iU ftY t J f m "TV d>( 14 ZdTHD ^ Durban and regional planning programme t> DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY N.U.L. ROMA LESOTHO AFRICA (RESEARCH REPORTj I Henk Huismpn 1S83 X t > u i Preface For the research programme undertaken in the context of the Urban and Regional Planning Programme, established at the National University of Lesotho in 1978, emphasis has been put on the spatial organization of develooment efforts and activities in the rural areas of Lesotho. This focus on the rural parts of the country also includes an assess ment of the role of urban centres in providing both agricultural and non-agricultursl services to the rural populati on. The present report focusses on the only urban centre in the Mafeteng District, viz. Mafeteng town. Services provided from the centre to the district's population are analysed in relation to the town 1s internal production structure. The information for this report was collected in 1981 by means of a sample survey of households and a number of special studies in which attention was paid to specific aspects of the urban economy and the town's population which were considered crucial for the analysis of structure and function of the town. The report should be seen as the urban counterpart to the URPP research report on households, production and resources in Mafeteng District, which was published in 1987. These reports will be followed by a planning survey of Mafeteng District, which contains an analysis of the district economy. -

Highlights Contents

LESOTHO METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES (LEKALA LA TSA BOLEPI) Ten-Day Agrometeorological Bulletin 21st – 31st January 2005 Issue No.10/2004-05 Date of Issue: 4 February 2005 Vol. 3 …dedicated to the agricultural community … aimed at harmonizing agricultural activities with weather and climate Contents Highlights Weather Summary Page 1 q Below normal rains recorded. Rainfall Situation q Cumulative rainfall normal countrywide. Page 1 q Temperature Crops conditions good at few localities. Page 1 q Infestation of insects at some places. Crop Stage and Condition Page 1 q Low rainfall expected for next dekad. Dekadal Outlook Page 1 Rainfall and Temperature Summaries Page 2 Glossary Page 3 The Director TEL: (+266) 22324374/22324425 Lesotho Meteorological Services FAX: (+266) 22325057/22350325 Agrometeorological Section E-mail:[email protected] P.O. Box 14515 http://www.lesmet.org.ls Maseru 100, Lesotho Issue No. 10/2004-05 Vol.3 21st –31st January 2005 WEATHER SUMMARY The percentage departure from normal cumulative 11th – 20 th January 2005 rainfall ranges from -12% to 32% (Table 1). The highest cumulative rainfalls of 721.5mm, The last dekad of January was dominated by 543.9mm and 509.4mm are recorded at Oxbow, surface trough. However, there was insufficient Leribe and Qacha’s Nek (Table 1 and Fig. 3). moisture over the interior as a result only partly Mafeteng, Maseru Airport, Moshoeshoe I and cloudy and warm conditions with few Phuthiatsana stations are the only stations which thundershowers occurred. have received cumulative rainfall of less than 400mm. RAINFALL SITUATION TEMPERATURE The last ten days of January received relatively low rainfall compared to the previous dekad (11th th The country experienced near normal – 20 January 2005) which was very wet. -

(LECSA)/Paris Evangelical Missionary Society (PEMS) in Meadowlands, Soweto, In

THE STRUGGLE OF THE LESOTHO EVANGELICAL CHURCH IN SOUTHERN AFRICA (LECSA)/PARIS EVANGELICAL MISSIONARY SOCIETY (PEMS) IN MEADOWLANDS, SOWETO, IN BECOMING A MISSIONAL ECCLESIA IN A LOCAL CONTEXT BY L.T. KGANYAPA SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEOLOGY IN MISSIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF. S.T. KGATLA 29 APRIL 2016 1 © University of Pretoria DECLARATION I declare that ‘The Struggle of the Lesotho Evangelical Church in Southern Africa (LECSA)/Paris Evangelical Missionary Society (PEMS) in Meadowlands, Soweto, in becoming a missional ecclesia in a local context’ is indeed my original work and all sources employed are duly indicated and acknowledged by means of references and a bibliography. Date: …………………………………………….2016 Signature: ……………………………………………. Leonard Tsidiso Kganyapa 2 © University of Pretoria ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude goes to Prof. S.T. Kgatla, my supervisor at the University of Pretoria (UP), for the supportive role he played throughout this research endeavour. I also extend a big thank you to the UP Bursary Fund for the bursary they awarded to me to study at the University. I would also like to thank Ms Brenda Nsanzya, faculty librarian at UP, for helping me obtain information from the library and search for books and articles pertaining to my research topic. Thanks also go to Ms Doris Mokgokolo, faculty administration at UP, for her assistance and patience with all of the changing dates and delays regarding the final submission of my dissertation. Thanks to Ms Mirriam Mabalane, faculty librarian at the University of Johannesburg (UJ) Soweto Campus, for helping me with access and space in the Research Commons. -

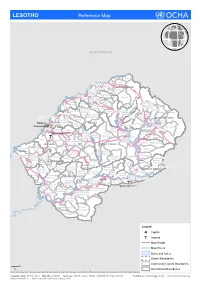

LESOTHO Reference Map

LESOTHO Reference Map SOUTH AFRICA Makhunoane Liqobong Likila Ntelle n Maisa-Phoka Ts'a-le- o d Moleka le BUTHA BUTHE a Lipelaneng C Nqechane/ Moteng Sephokong Linakeng Maputsoe Leribe Menkhoaneng Sekhobe Litjotjela Likhotola/ LERIBE Hleoheng Malaoaneng Manka/ Likhakeng Matlameng Mapholaneng/ Fobane Koeneng/ Phuthiatsana Kolojane Lipetu/ Kao Pae-la-itlhatsoa -Leribe Fenyane Litsilo -Pae-la-itlhatsoa Mokhachane/ Mamathe/Bulara Mphorosane Molika-liko Makhoroana Limamarela Tlhakanyu/Motsitseng Teyateyaneng Seshote Mapholaneng/ Majoe-Matso/ Meno/ Lekokoaneng/Maqhaka Mohatlane/ Sebetia/Khokhoba Pae-la-itlhatsoa Matsoku -Mapholaneng MOKHOTLONG Lipohong Thuapa-Kubu/ Moremoholo/ Katse Popa Senekane BEREA Moshemong Maseru Thuathe Koali/ Taung/Khubelu Mejametalana p Mokhameleli Semenanyane Mokhotlong S Maluba-lube/ Mateanong e Maseru Suoane/ m Rafolatsane Thaba-Bosiu g Ratau e Liphakoeng n Bokong n e a Ihlo-Letso/ Mazenod Maseru Moshoeshoe l Setibing/ Khotso-Ntso Sehong-hong e Tsoelike/ Moeketsane h Pontseng/ Makopoi/ k Mantsonyane Bobete p Popa_MSU a Likalaneng Mahlong Linakaneng M Thaba-Tseka/ Rothe Mofoka Nyakosoba/Makhaleng Maboloka Linakeng/Bokhoasa/Manamaneng THABA TSEKA Kolo/ MASERU Setleketseng/ Tebang/ Matsieng Tsakholo/Mapotu Seroeneg S Mashai e Boleka n Tsa-Kholo Ramabanta/ q Methalaneng/ Tajane Moeaneng u Rapo-le-boea n Khutlo-se-metsi Litsoeneng/Qalabane Maboloka/ y Sehonghong Thaba-Tsoeu/ Monyake a Lesobeng/ Mohlanapeng Mathebe/ n Sehlaba-thebe/ Thabaneng Ribaneng e Takalatsa Likhoele Moshebi/ Kokome/ MAFETENG Semonkong Leseling/ -

Hiog-OOOO-G1 62

________________________'FNMR 122 hIOG-OOOO-G1 62 Quantitative analyses of Lesotho's offici1,,yteId data for maize and sorghum 4. ERSONPAL AUTHOU (100) Eckertt Jerry 5. )RPORATEAUTHORS (101) Ooloo State Univ. Dept. of Economics 6. DOCUMENT DATE (110) =7. NUMBER OF PAGES (120) . ARC NUMBER (170) 1980 35p. LT633.1.E19 9. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION (130) Colo. State 10. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (500) (In LASA research rpt.no.8) (Financial support rendered under AID cooperative agreement no.: AID/ta-CA-I under AID basic memorandum no.: AID/ta-BMA-6) 11. ABSTRACT (950) 12.DESCRIPTORS (920) 13. PROJECT NUMBER (ISO) Maize Data collection Lesotho Methodology Sorghum Statistics 14. ONTRACT NO.(I4 ) 1. ONTRACT Yield Productivity TYPE (140) Rainfall Analysis AID/ta-BMA-6 16. 1YPE OF DOCUMENT (160) AM) 90,7 (10,79) LESOTHO AGRICULTURAL SECTOR ANALYSIS PROJECT Ministry of Agriculture Kingdom of Lesotho Department of Economics Colorado State University QUANTITATIVE ANALYSES OF LESOTHO'S OFFICIAL YIELD DATA FOR MAIZE AND SORGHUM Research Report No. 8 Lesotho Agricultural Sector Analysis Project by Jerry Eckert Agricultural Economist QUANTITATIVE ANALYSES OF LESOTHO'S OFFICIAL YIELD DATA FOR MAIZE AND SORGHUM Research Report No. 8 Lesotho Agricultural Sector Analysis Project by Jerry Eckert Agricultural Economist Prepared with support of the United States Agency for International Development, Cooperative Agreement AID/ta-CA-l. All expressed opinions, conclusions or recommendations are those of the author and not of the funding agency, the United States Government -

Qacha's Nek District Council

QACHA’S NEK DISTRICT COUNCIL Information Handbook 2009 0 Handbook QACHA’S NEK DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL GOVERNMENT DISTRICT INFORMATION HANDBOOK June 2009 A COMPILATION OF CRUCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE DISTRICT (DISAGGREGATED COUNCIL-WISE) Ministry of local Government and Chieftainship German Technical Cooperation Department of Planning Kingdom of Lesotho Kingdom of Lesotho Information Handbook 2009 1 Handbook Prepared by: Department of Planning, Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Supported by: GTZ Lesotho The Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship (MOLGC) through its Department of Planning, remains the owner of this handbook. However, there shall be no copy- right restrictions over the use or replication of the whole or parts of this handbook. This is an approach for utiliza- tion by the interested parties and is entirely in the public domain. However, no changes shall be made to the handbook and reprinted thus without prior permission of MOLGC. Version dated: June 2009 Pictures provided by: The Age Multimedia Publishers Design/Layout by: The Age Multimedia Publishers Printed by: Qacha’s nek Publisher’s contact details, Maseru: District Council Ministry of Local Government, P.O. Box 686, Maseru 100, Lesotho. Tel.: +266 22 325331 Fax: +266 22 311269 Contact details, Qacha’s Nek: District Council, P.O. Box 1, Qacha’s Nek 600, Lesotho. 2009 Tel.: +266 22 950216/950261 Fax: +266 22 950524 2 Qacha’s Nek District Council Contents Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………….............. 04 Qacha’s Nek District Map…………………………………………………………................. 05 Introduction………………………………………………………………………...........…….. 06 Background to Local Government in Lesotho……………………………............…………. 07 Methodology…………………………………………………………………...........…………. 08 1. Profile of Community Councils……………………………………...……………… 09 2. Social Indicators……………………………………………………...……………… 10 3. Gender Aspects……………………………………………………....………………. -

Competition Issues in the Transport Sector in Lesotho

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Competition issues in the Transport Sector in Lesotho By Chabeli J. RAMOLISE New York and Geneva, 2011 The views expressed in this study are those of the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD Secretariat. NOTE UNCTAD serves as the focal point within the United Nations Secretariat for all matters related to competition policy. UNCTAD seeks to further the understanding of the nature of competition law and policy and its contribution to development and to create an enabling environment for an efficient functioning of markets. UNCTAD’s work is carried out through intergovernmental deliberations, capacity building activities, policy advice, and research and analysis on the interface between competition policy and development. UNCTAD’s work on competition law and policies falls within the framework of the Set of Multilaterally Agreed Principles and Rules for the Control of Restrictive Business Practices (the “United Nations Set of Principles and Rules on Competition”), adopted by the General Assembly in 1980. The set seeks, inter alia, to assist developing countries in adopting and enforcing effective competition law and policy that are suited to their development needs and economic situation. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. -

Annexure 1: Lesotho Villages and Their Corresponding Code

Annexure 1: Lesotho villages and their corresponding code ID Village 46 Tlhanyaku 92 Rafolatsane 1 Liqobong 47 Bela-Bela 93 Khokhoba 2 Boiketsiso 48 Mphorosane 94 Liphakoeng (Mokhotlong) 3 Makhunoane 49 Mokhachane 95 Bokong 4 Qholaqhoe 50 'Mamathe 96 Sehong-hong 5 Namahali 51 Seshote 97 Setibing 6 Maama 52 Lehana-le-molapa 98 Khohlontso 7 Tumane 53 Majoe-Mats'o 99 Bobete 8 Matlakeng 54 Meno 100 Bobatsi 9 Chaba 55 Mapoteng 101 Mazenod 10 Mopeli 56 'Makhoroana 102 Makopoi 11 Qalo 57 Malotoaneng 103 Popa (Maseru) 12 Khukhune 58 Sebetia 104 Moeketsane 13 Nqechane 59 Lekokoaneng 105 Rothe 14 Butha-Buthe Urban 60 Mapholaneng 106 Linakeng (Mokhotlong) 15 Sekubu 61 Suoane 107 Mantsonyane 16 Tsime 62 'Meta 108 Mofoka 17 Soloane 63 Mohatlane 109 Maboloka (Thaba Tseka) 18 Linakeng (Butha Buthe) 64 Motsitseng 110 Likalaneng 19 Likhutlong 65 Mongolo 111 Roma 20 Leribe 66 Lebese 112 Lirahalibonoe 21 Ha Mots'eare 67 Mika 113 Nyakosoba 22 Mohobollo 68 Koali 114 Thaba Moei 23 Pela Ts'oeu 69 Maqhaka 115 Linakeng (Thaba Tseka) 24 Hlotse 70 Matsoku 116 Manamaneng 25 Maputsoe 71 Malingoaneng 117 Makhaleng 26 Pela-ts'oeu 72 Kosetabole 118 Lits'oeneng 27 Tsikoane 73 Moshemong 119 Bokhoasa 28 Likhakeng 74 Popa (Mokhotlong) 120 Matsieng 29 Matlameng 75 Foso 121 Kolo 30 Peka 76 Taung 122 Mohlanapeng 31 Mahobong 77 Semenanyane 123 Mochochoko 32 Hleoheng 78 Thupa-Kubu 124 Mahlong 33 Mothae 79 Mokhameleli 125 Setleketseng 34 Pitseng 80 Khamolane 126 Thaba-nts'o 35 Thaba Phats'oa (Leribe) 81 Thuathe 127 Tsakholo 36 Lejone 82 Tsoelike 128 Serooeng 37 Mokomahatsi 83 -

Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in LESOTHO Research Highlights – Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in Lesotho

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in LESOTHO Research Highlights – Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in Lesotho Funded by ‘Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme’ (ASAP) Phase 2. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Produced by the University of Cape Town Undertaken in support of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) by: African Climate & Development Initiative (www.acdi.uct.ac.za) Climate System Analysis Group (www.csag.uct.ac.za) Environmental Policy Research Unit (www.epru.uct.ac.za) Recommended citation: Hunter. R., Crespo. O., Coldrey, K, Cronin, K, New, M. 2020. Research Highlights – Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in Lesotho. University of Cape Town, South Africa, undertaken in support of Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme’ (ASAP) Phase 2. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Rome. The content and presentation of material in this report is the sole responsibility of the Authors and does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Fund for Agricultural Development of the United Nations. The project team gratefully acknowledges the support of IFAD towards this research and in particular the IFAD country office and project staff. The project team thanks the various stakeholders and contributors who have shared their knowledge and time during this study. CONTENTS Background and context . 1 Summary results . 2 Method and Approach . 3 Impacts........................................................................................3 Figure 1. Demonstration example of the distribution of crop suitability index. generated using EcoCrop ........4 Adaptive Capacity ...............................................................................5 Table 1. Ranked Adaptive Capacity (AC) indicator scores for all regions of Lesotho ..........................5 Climate projections . 6 Projected changes to Temperature in Lesotho by 2050 . -

Leribe District Local Governance & Non-State Actors Support Programme - LGNSP & Non-State Actors Support Programme Local Governance

INFORMATION HANDBOOK Leribe District Local Governance & Non-state actors Support Programme - LGNSP & Non-state actors Support Programme Local Governance Report 1 2009 Edited by: Miguel Fernández Trillo-Figueroa Contributions by: Moipone Letsie, Mpopo Tsoele, Matseliso Mapetla Series editor: François Dronnet, Matseliso Ntsoelikane Photos by: Miguel Fernández Trillo-Figueroa INFORMATION HANDBOOK Leribe District Report 1 2009 This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of its author(s) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, the views of the Local Governance and Non-state actors Support Programme (LGNSP) or any of the Lesotho institutions participating in this programme. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for use which might be made of the following information. Published by LGNSP in Maseru (Lesotho), 2009 ISBN 978-92-79-12038-1 © European Communities, 2009 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Copies of this publication can be obtained by writing to: LGNSP Programme Management Unit, Private Bag A478, Maseru 100, Kingdom of Lesotho or to [email protected]. When ordering, please quote ISBN number. This publication can also be downloaded from http://www. lgnsp.co.ls. For further information on the European Union: http://ec.europa.eu/world http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid http://www.dellso.ec.europa.eu/ Designed by: The Media Chilli Illustrations by: Santiago Fernández Trillo-Figueroa Photos by: Miguel Fernández Trillo-Figueroa Produced and printed by: Saysouk Creation graphique s.c.s.