From Citizenship to Voting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HILARY LANE (732) 614-0399 • [email protected]

HILARY LANE (732) 614-0399 • [email protected] BROADCASTING EXPERIENCE: News 12 NJ - Freelance Reporter, Edison, NJ 09 /2018 - Present • Write stories, cover breaking news, and file live reports for News 12 daytime and nighttime programming. • Work collaboratively to brainstorm and pitch longer form stories and program ideas. CBS News, New York, NY; Correspondent August 2018- February 2020 • Freelance Correspondent at CBS Newspath • Consistently featured on Network programming including CBS Morning News, CBS Weekend News, and CBSN. • Provides live shots and content for 200+ affiliates across the country • Covered the biggest stories of the year including Hurricane Michael, Pittsburgh Synagogue Shooting, and the death of former President George H.W. Bush WUSA 9 (CBS), WASHINGTON, DC; /MMJ/ Fill-in Anchor August 2016- July 2018 ● Report live breaking news for 2.5 hour morning show. ● Regularly contribute exclusive, enterprised, investigative stories to the Special Assignments Unit. ○ Superintendent in MD’s second-largest school district resigned after exclusive report exposing secret pay raises. ○ School officials are increasing pest patrol services after exclusive story about unsanitary cafeteria conditions and inspection failures in local public schools. ○ Virginia State Senator introducing legislation to ensure safe drinking water after investigative report into contaminated water concerns around a multi-billion dollar energy plant. WFMZ (IND), Allentown, PA; News Reporter October 2014- August 2016 ● Lead reporter on multiple national stories in coverage area including: Deadly Amtrak train derailment, Pope Francis’ visit to Philadelphia, violent protests in Philadelphia, NORAD blimp escaping military base and crashing in central Pennsylvania, missing autistic boy found dead in local canal, and 3-year-old beaten to death by mother and boyfriend. -

March 29 - April 4, 2020 Time Sta

March 29 - April 4, 2020 Time Sta. Sun, 3/29 Sta Mon, 3/30 Sta Tues, 3/31 Sta Wed, 4/1 Sta Thur, 4/2 Sta Fri, 4/3 Sta Sat, 4/4 Time 6am KTVA CBS Sunday KTUU Ch. 2 News KTUU Ch. 2 News KTUU Ch. 2 News KTUU Ch. 2 News KTUU Ch. 2 News KTVA CBS Saturday 6am 6:30 Morning Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning 6:30 7:00 The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show Lucky Dog 7:00 7:30 Face the Nation Innovation Nation 7:30 8:00 Animal Rescue 8:00 8:30 KTBY Recipe.tv Dog Tales 8:30 9:00 KTVA NCAA Basketball KYUR The View KYUR The View KYUR The View KYUR The View KYUR The View SSN Sports 9:00 9:30 1985 Championship CBS Sports 9:30 10:00 KTVA Price is Right KTVA Price is Right KTVA Price is Right KTVA Price is Right KTVA Price is Right Special 10:00 10:30 NCAA Basketball Movie: 10:30 11:00 1997 Championship The Young & The Young & The Young & The Young & The Young & Nicholas Nickleby 11:00 11:30 The Restless The Restless The Restless The Restless The Restless 11:30 12pm KYES Movie: Modern Family Modern Family Modern Family Modern Family Modern Family 12pm 12:30 Flags of Our Fathers The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful 12:30 1:00 The Talk The Talk The Talk The Talk The Talk Dr. -

Latino Immigrant Civic Engagement in Nine US Cities

CONTEXT MATTERS: Latino Immigrant Civic Engagement in Nine U.S. Cities Series on LatIno ImmIGrant CIVIC enGAGEment charlotte, nc • chicago, il • fresno, ca • las vegas, nv • los angeles, ca • omaha, ne • san jose, ca • tucson, az • washington, dc CONTEXT MATTERS: LatINO ImmIGrant CIVIC ENGAGement IN NIne U.S. CITIes Series on Latino Immigrant Civic Engagement Authors: Xóchitl Bada University of Illinois at Chicago Jonathan Fox University of California, Santa Cruz Robert Donnelly Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Mexico Institute Andrew Selee Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Mexico Institute Authors: Xóchitl Bada, Jonathan Fox, Robert Donnelly, and Andrew Selee Series Editors: Xóchitl Bada, Jonathan Fox, and Andrew Selee Coordinators: Kate Brick and Robert Donnelly Translator: Mauricio Sánchez Álvarez Preferred citation: Xóchitl Bada, Jonathan Fox, Robert Donnelly, and Andrew Selee. Context Matters: Latino Immigrant Civic Engagement in Nine U.S. Cities, Reports on Latino Immigrant Civic Engagement, National Report. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, April 2010. © 2010, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Cover image: Upper photo: Demonstrating against HR 4437 and the criminalization of the undocumented, thousands of immigrants and supporters filled the streets of Los Angeles two times on May 1, 2006—first, with a march downtown; then, with another through the Wilshire District’s Miracle Mile, where this photo was taken. Chants heard included, “¡Aquí estamos y no nos vamos!” Photo by David Bacon. Used by permission. Lower photo: Naturalization rates of Latin America-born immigrants, particularly Mexicans, increased sharply over 1995-2005 for a variety of reasons. Photo of a naturalization ceremony by David McNew/Getty Images News. -

November 29 - December 5, 2020 Time Sta

November 29 - December 5, 2020 Time Sta. Sun, 11/29 Sta Mon, 11/30 Sta Tues, 12/1 Sta Wed, 12/2 Sta Thur, 12/3 Sta Fri, 12/4 Sta Sat, 12/5 Time 6am KYES CBS Sunday Morning KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KYES CBS Saturday 6am 6:30 Morning 6:30 7:00 The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show Lucky Dog 7:00 7:30 Face the Nation Innovation Nation 7:30 8:00 NFL Today Animal Rescue 8:00 8:30 Inside College Bball 8:30 9:00 NFL KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make NCAA Basketball 9:00 9:30 A Deal A Deal A Deal A Deal A Deal Baylor @ Gonzaga 9:30 10:00 Price is Right Price is Right Price is Right Price is Right Price is Right 10:00 10:30 10:30 11:00 The Young & The Young & The Young & The Young & The Young & College Football Today 11:00 11:30 The Restless The Restless The Restless The Restless The Restless College Football 11:30 12pm News at 12 News at 12 News at 12 News at 12 News at 12 12pm 12:30 NFL The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful 12:30 1:00 The Talk The Talk The Talk The Talk The Talk 1:00 1:30 1:30 2:00 Dr. -

The Other Mr. Turner

OU alumnus Ed Turner has stocked his CNN staffwith aggressive Sooner go-getters . The Other Mr. Turner at CNN hen calling the executive News Network, TBS' most ambitious Ted Turner launched his full-time offices of the Turner Broad- and surprisingly successful venture. news experiment, the media skeptics casting System in Atlanta, While Ted Turner is busy making were unanimous. Labeling CNN Wit pays to enunciate. A mumbled re- news, Ed Turner concentrates on mak- "Turner's Folly" and "Chicken Noodle quest can get you either Ted Turner, ing the news available, 24 hours a day, News," the major networks predicted the flamboyant, controversial favorite to 31 .5 million cable viewers abject failure. No one would talk to son of the South who heads this com- worldwide . They are both very good CNN, they reasoned; no one would ad- munications/sports empire, or Ed at their jobs . vertise; no one would watch. Turner's Turner, the hard-driving trans- Four-and-one-half years ago, when profitable WTBS, Atlanta's cable-wise planted Sooner whose considerable Superstation, would never be able to journalistic talents have made him sustain the losses sure to be incurred the number two operative at Cable By CAROL J . BURR by CNN . Continued 1985 WINTER 11 done in Washington . At United Press International Television News in New York, his next professional stop, he found a news organization of sorts al- ready in place, but one which "had not yet entered the electronic world." "In this day and age, you ordinarily don't have a chance to build a news group from nothing," he explains, "be- cause they're usually in place. -

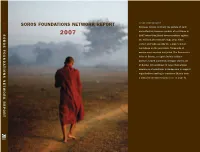

Soros Foundations Network Report

2 0 0 7 OSI MISSION SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT C O V E R P H O T O G R A P H Y Burmese monks, normally the picture of calm The Open Society Institute works to build vibrant and reflection, became symbols of resistance in and tolerant democracies whose governments SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT 2007 2007 when they joined demonstrations against are accountable to their citizens. To achieve its the military government’s huge price hikes mission, OSI seeks to shape public policies that on fuel and subsequently the regime’s violent assure greater fairness in political, legal, and crackdown on the protestors. Thousands of economic systems and safeguard fundamental monks were arrested and jailed. The Democratic rights. On a local level, OSI implements a range Voice of Burma, an Open Society Institute of initiatives to advance justice, education, grantee, helped journalists smuggle stories out public health, and independent media. At the of Burma. OSI continues to raise international same time, OSI builds alliances across borders awareness of conditions in Burma and to support and continents on issues such as corruption organizations seeking to transform Burma from and freedom of information. OSI places a high a closed to an open society. more on page 91 priority on protecting and improving the lives of marginalized people and communities. more on page 143 www.soros.org SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT 2007 Promoting vibrant and tolerant democracies whose governments are accountable to their citizens ABOUT THIS REPORT The Open Society Institute and the Soros foundations network spent approximately $440,000,000 in 2007 on improving policy and helping people to live in open, democratic societies. -

57Th Socal Journalism Awards

FIFTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL5 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA7 JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th 57 ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 48 NOMINATIONS JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB 57TH SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS WELCOME Dear Friends of L.A. Press Club, Well, you’ve done it this time. Yes, you really have! The Los Angeles Press Club’s 57th annual Southern California Journalism Awards are marked by a jaw-dropping, record-breaking number of submissions. They kept our sister Press Clubs across the country, who judge our annual competition, very busy and, no doubt, very impressed. So, as we welcome you this evening, know that even to arrive as a finalist is quite an accomplishment. Tonight in this very Biltmore ballroom, where Senator (and future President) John F. Kennedy held his first news conference after securing his party’s nomination, we honor the contributions of our colleagues. Some are no longer with Robert Kovacik us and we will dedicate this ceremony to three of the best among them: Al Martinez, Rick Orlov and Stan Chambers. The Los Angeles Press Club is where journalists and student journalists, working on all platforms, share their ideas and their concerns in our ever changing industry. If you are not a member, we invite you to join the oldest organization of its kind in Southern California. On behalf of our Board, we hope you have an opportunity this evening to reconnect with colleagues or to make some new connections. Together we will recognize our esteemed honorees: Willow Bay, Shane Smith and Vice News, the “CBS This Morning” team and representatives from Charlie Hebdo. -

Pub Type Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 233 705 IR 010 796' TITLE Children and Television. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications, Consumer Protection, and Finance of the Committee on Energy and ComMerce, House of Representatives, Ninety-Eighth Congress, First Session. Serial No. 98-3. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Eneygy and Commerce. PUB DATE- 16 Mar 83 NOTE 221p.; Photographs and small print of some pages may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE --Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09'Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cable Television; *Childrens Television; Commercial Television; Educational Television; Federal Legislation; Hearings; Mass Media Effects; *ProgrAming (Broadcast); *Public Television; * Television Research; *Television Viewing; Violence IDENTIFIERS Congress 98th ABSTRACT Held, during National Children and Television Week, this hearing addressed the general topic of television and its impact on children, including specific ,children's televisionprojects and ideas for improving :children's television. Statements and testimony (when given) are presented for the following individuals and organizations: (1) John Blessington,-vice president, personnel, CBS/Broadcast Group; (2) LeVar Burton, host, Reading Rainbow; (3) Peggy Charren, president, National Action for Children's Television; (4) Bruce Christensen, president, National Association of;Public Television Stations; (5) Edward 0. Fritts, president, National Association of Broadcasters; (6) Honorable John A. Heinz, United States Senator, Pennsylvania; (7) Robert Keeshan, Captain Kangaroo; \(8) Keith W. Mielke, associate vice president for research, Children's Television Workshop; (9) Henry M. Rivera, Commissioner, , Federal Communications Commission; (10) Sharon Robinson, director, instruction and Professional Development, National Education Association; (11) Squire D. Rushnell, vice president, Long Range Planning and Children's Television, ABC; (12) John A. -

Groups Pushing an Anti American Agenda That Are Receiving Support from Soros

GROUPS PUSHING AN ANTI AMERICAN AGENDA THAT ARE RECEIVING SUPPORT FROM SOROS Many protests and riots were uncovered to have consisted of paid individuals, some of whom had no affinity for the cause or even knew much about what they were protesting. The groups have a common organizer, Soros, who was either a founder or financial supporter or influencer. We have names of global companies, tax exempt entities, non government organizations (NGOs), media affiliations, owners, founders, members, supporters, vendors, contractors, attorneys, accountants, banks, U.S. government affiliations and foreign government affiliations. Many of the groups were formed to pretend to be supportive of particular causes that are contrary to the ideology of the subversive groups so the bad actors could infiltrate including placing their own regimented personnel and making demands before they contributed funds. Advancement Project Air America Radio Al Haq All of Us or None Alliance For Global Justice Alliance For Justice America Coming Together America Votes America’s Voice American Bar Association Commission on Immigration Policy American Bridge 21st Century America Civil Liberties Unions American Constitution Society American Family Voices American Federation of Techers American Friends Service Committee American Immigration Council American Immigration Law Foundation American Independent News Network American Institute For Social Justice American Library Association American Prospect INC Applied Research Center Arab American Institute Aspen Institute ACORN Ballot -

Informed & Engaged Ep 11

Informed & Engaged Ep 11 [00:01:11] Hi, everyone. Welcome to the 11th edition of Informed & Engaged today. I am absolutely thrilled to have Brian Stelter join us. Brian Stelter, as many of you know, is the chief media correspondent for CNN Worldwide. He's the host of Sunday's Reliable Sources and he is the author with a wonderful team of the most reliable newsletter, daily newsletter for anyone in the media business or anyone who cares about the impact of media on our democracy. Welcome, Brian. Thank you for joining us. [00:01:51] Thank you for the plugs. Thank you for reading the newsletter. [00:01:55] Hey, hey. It is a must read. It must be with great links with really terrific links. Because what you do in the newsletter is you really help steer and direct your users to really important, not just your reporting, but other very important reporting taking place across the media landscape. So today, Brian, we're really thrilled to talk about your new book, Hoax. [00:02:25] And you wrote a book that The New York Times where full disclosure, Brian and I both worked together at The New York Times. In fact, we sat next to each other over a period of time at The New York Times. [00:02:43] So in The New York Times book review, it was described as this book provides a thorough and damning exploration of the incestuous relationship with Donald Trump and his favorite television channel, Fox News. So the author, the title of the book Hoax Donald Trump and Fox News and the Dangerous Distortions of the Truth is based on three years of reporting and interviews with more than 250 former Fox staff members and current Fox staff members. -

3/4" News List

% inch Videotape News 1. CBS Evening News: corporate censorship: D. Wildmon 2. Charlie Rose Show: N. Lear: 6-26-81: part 1 3. Charlie Rose Show: T. Podesta, D. Wildman: 8-6-81 4. Moral Majority: Washington for Jesus Rally, 1980 5. Harvester Hour: "Is the Moral Majority Moral?": E. Palk, 11-1-80 6. National Conservative Forum 7. That's Entertainment: PFAW: N. Lear: 10-2-81 8. The Radical Religious Right: Their Time, Their station: Union of American Hebrew Congregation 9. ABC Special: TV, The Moral Battleground: parts 1-4 10. People to People: The New Right, 7-23-81 11. WCVB Boston: C. Thomas and B. Frank: part 2: B. Alley: 10-4-81 12. Montage: M. Mcintyre on PFAW: 11-16-81 13. 700 Club: Freedom of Religion 9-30-81 14. KDLH Virginia: record and book burning: 11-11-81 15. KDLH Virginia: record and book burning: 11-11-81 16. The Morning Show: J.Falwell: 3-7-84 17. Beyond Easy Answers: "Religion in Politics, Sin or Salvation: 3-3-82 18. Donahue: D. Wildmon: 10-6-80 19. Jerry Falwell 20. Wake Up America! We are All Hostages!: J. Robison 21. Who Controls TV: debate: Brown and Thomas: part 1: 2-2-82 22. Who Controls TV: debate: Brown and Thomas: part 1 23. Who Controls TV: debate: part 2 24. Who Controls TV: debate: part 2 25. WDVM Maryland: Hatiesburg, MD Home for Girls 3-2-82 26. WDVM Maryland: Hatiesburg, MD Home for Girls (No Sound) 27. The Robin Byrd Show: PFAW's PSA: 7-8-81 28. -

Jeff Werber, D.V.M

CURRICULUM VITAE Jeff Werber, D.V.M. 9330 Duxbury Road, Los Angeles California 90034 310-980-7013 ______________________________________________________________________ MEDIA CREDITS-Television/Radio/Online 2020 KABC-TV, AirVet and Pet Telemedicine 2019 KTLA-TV, Aging Pets & AirVet Telemedicine 2019 KABC-TV, Obesity in Pets—and their Owners 2019 KTLA-TV, Summer Safety 2018 KCAL/KCBS-TV, Pets and Halloween 2018 KABC-TV, Capnocytophaga Infection 2018 KABC-TV, Tick Borne Diseases 2018 Inside Edition, Pets and Fire Dangers 2018 KCAL/KCBS-TV, Holiday Hazards for Pets 2018 KCAL/KCBS-TV, Warm Weather Wellness 2017 Fox News Edge, Pets and Pot 2017 Fox News Edge, Back to School 2017 KTNV-Las Vegas ABC, Summer Pet Safety 2016 Marilu Henner Show, “Holiday Hazards” 2016 Fox News Edge Pick-up, “Holiday Hazards” 2016 KGO Radio, “Bringing new pets in the home” 2016 Fox Las Vegas, Summer Safety Tips 2016 Fox News Edge Pickup, Pet Allergies 2016 Fox News Edge Pickup, Pet Safety tips 2016 CBS/KCAL 9 LA, Summer Safety Tips 2016 Fox News Edge, Pet safety tips for spring 2016 John Tesh Radio, Connie Sellecca interview 2016 Fox Las Vegas, Discussing pet obesity with tips and tools 2016 CBS News, Common signs to look out for if your pet is obese 2016 Fox News Health, How to keep your pet safe during a winter storm 2016 Fox News Edge Pick-up, Winter weather tips/ pet obesity 2015 Fox News, The New Canine Influenza Virus 2015 Fox News, Medical Marijuana for Pets 2014 Fox and Friends, Pros and Cons of Medical Marijuana for Pets 2014 Fox News This Morning-Las Vegas-Valentine’s