Anarchist Women and the “Sex Question”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ryley, Peter. "The English Individualists." Making Another World Possible: Anarchism, Anti- Capitalism and Ecology in Late 19Th and Early 20Th Century Britain

Ryley, Peter. "The English individualists." Making Another World Possible: Anarchism, Anti- Capitalism and Ecology in Late 19th and Early 20th Century Britain. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. 51–86. Contemporary Anarchist Studies. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501306754.ch-003>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 12:22 UTC. Copyright © Peter Ryley 2013. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The English individualists There is a conventional historical narrative that portrays the incremental growth of collectivist political economy as something promoted and fought for by popular movements, an almost inevitable part of the process of industrial modernization. Whether described in class terms as the ‘forward march of labour’ or ideologically as the rise of socialism, the narrative is broadly the same. The old certainties had to give way in the face of modern mass societies. This poses no problem for anarcho-communism. It can be accommodated comfortably on the libertarian wing of collectivism. But what of individualism? It seems out of place, a curiosity; the last gasp of a liberal England that was about to die. Perhaps that explains its comparative neglect. Yet seen as part of the radical milieu of the time, it seems neither anomalous nor a fringe movement. It stood firmly in the tradition of a left libertarian radicalism that was a serious competitor of the collectivist left. There were two main groupings of individualists in late Victorian Britain. -

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

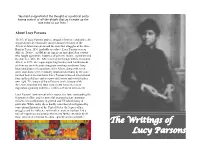

The Writings of Lucy Parsons

“My mind is appalled at the thought of a political party having control of all the details that go to make up the sum total of our lives.” About Lucy Parsons The life of Lucy Parsons and the struggles for peace and justice she engaged provide remarkable insight about the history of the American labor movement and the anarchist struggles of the time. Born in Texas, 1853, probably as a slave, Lucy Parsons was an African-, Native- and Mexican-American anarchist labor activist who fought against the injustices of poverty, racism, capitalism and the state her entire life. After moving to Chicago with her husband, Albert, in 1873, she began organizing workers and led thousands of them out on strike protesting poor working conditions, long hours and abuses of capitalism. After Albert, along with seven other anarchists, were eventually imprisoned or hung by the state for their beliefs in anarchism, Lucy Parsons achieved international fame in their defense and as a powerful orator and activist in her own right. The impact of Lucy Parsons on the history of the American anarchist and labor movements has served as an inspiration spanning now three centuries of social movements. Lucy Parsons' commitment to her causes, her fame surrounding the Haymarket affair, and her powerful orations had an enormous influence in world history in general and US labor history in particular. While today she is hardly remembered and ignored by conventional histories of the United States, the legacy of her struggles and her influence within these movements have left a trail of inspiration and passion that merits further attention by all those interested in human freedom, equality and social justice. -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

A Bibliography of Henry David Thoreau

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HENRY DAV ID THOREAU COMPILED BY FRANCIS H ALLEN BOSTON AND N EW YORK HOU G HTON MI FFLIN COMPANY MDCCCCVIII ' 1 131 Z m h u t/ u 04 ] 7 617 1 W W PYRIGHT IN” BY HOU HTON “M 00. , , G ALL RIGHTS RES ERVED FIV E HU NDRED AND THIRTY COPIES PRINTED “ 0 3 3 7 7 PREFACE THE ener a a n of is book is ba sed on th e g l pl th iio r a e ies w e n e r s ic a e rece iith s ie v t b bl g ph h h h p d d , b u tcer ta in e n in a o a r tu r es a ve ee m a e d p h b d , c or da nce wiw a th e a r ticu la r th h ta ppea red to be p em a n h e d ds of th e m a tter to be pr esented . T div sion- - ie n a is a r e owe er se ex a na tor v h d g , h , lf pl y , so ta tit see ce n n m s u nne ss r s ti h a y to a y a y h g u r ter er e a s to th e contents a nda r r a n em ent f h h g , a ndwe m a y pr oceed a tonce to th e a cknowledg m ents w in on ic c m w l o o m it a ll o er i t i h h , h h b b r a h er s th e com iler of is o w h e t o o es to t g p , p h b k m n h a er son w o a ve e him in h or s . -

Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought

CHAPTER 16 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought Crispin Sartwell Introduction Although it is unlikely that any Americans referred to themselves as “anar- chists” before the late 1870s or early 1880s, anti-authoritarian and explicitly anti-statist thought derived from radical Protestant and democratic traditions was common among American radicals from the beginning of the nineteenth century. Many of these same radicals were critics of capitalism as it emerged, and some attempted to develop systematic or practical alternatives to it. Prior to the surge of industrialization and immigration that erupted after the Civil War—which brought with it a brand of European “collectivist” politics associ- ated with the likes of Marx and Kropotkin—the character of American radi- calism was decidedly individualistic. For this reason among others, the views of such figures as Lucretia Mott, William Lloyd Garrison, Josiah Warren, Henry David Thoreau, Lysander Spooner, and Benjamin Tucker have typically been overlooked in histories of anarchism that emphasize its European communist and collectivist strands. The same is not true, interestingly, of Peter Kropotkin, Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre and other important social anarchists of the period, all of whom recognized and even aligned themselves with the tradition of American individualist anarchism. Precursors In 1637, Anne Hutchinson claimed the right to withdraw from the Puritan the- ocracy of the Massachusetts Bay Colony on the sole authority of “the voice of [God’s] own spirit to my soul.”1 Roger Williams founded Rhode Island on similar grounds the previous year. Expanding upon and intensifying Luther’s 1 “The Trial and Interrogation of Anne Hutchinson” [1637], http://www.swarthmore.edu/ SocSci/bdorsey1/41docs/30-hut.html. -

Socialism, Feminism, and Suffragism, the Terrible Triplets, Connected by the Same Umbilical Cord, and Fed from the Same Nursing Bottle, by B.V

Socialism, feminism, and suffragism, the terrible triplets, connected by the same umbilical cord, and fed from the same nursing bottle, by B.V. Hubbard SOCIALISM FEMINISM AND SUFFRAGISM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK COLLECTION CHAPMAN CATT SUBJECT Section V Woman - Sociology No 27 SOCIALISM, FEMINISM, AND SUFFRAGISM, THE TERRIBLE TRIPLETS CONNECTED BY THE SAME UMBILICAL CORD. AND FED FROM THE SAME NURSING BOTTLE By B. V. HUBBARD Chicago: American Publishing Company 1820 City Hall Square Bldg. Copyright, 1915 by B. V. Hubbard DEDICATION To the innumerable multitude of motherly women, who love and faithfully serve their fellowmen with a high regard for duty a veneration for God, respect for authority, and love for husband, home and heaven, whether such a woman is the mother of children, or whether she has been denied motherhood and bestows her motherliness upon all who are weak, distressed and afflicted. This book is also dedicated to the man who is, in nature, a knight and protector of the weak, the defender of the good, who shrinks no responsibility, who has a paternal love of home, a patriotic affection for country, veneration for moral and religious precepts, and who has the courage to combat evil and fight for all that which is good. CONTENTS SOCIALISM Chapter Page Introduction 9 I. Socialism Defined—Immediate Demands Not Socialistic—Ultimate Demands Real Socialism 13 Socialism, feminism, and suffragism, the terrible triplets, connected by the same umbilical cord, and fed from the same nursing bottle, by B.V. Hubbard http://www.loc.gov/resource/rbnawsa.n6027 II. The Materialistic Conception of History—Consequences of the Materialistic Conception of History, Denies the Natural Rights of Man 21 III. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Was My Life Worth Living? by Emma Goldman [Published in Harper's Monthly Magazine, Vol

Published Essays and Pamphlets Was My Life Worth Living? by Emma Goldman [Published in Harper's Monthly Magazine, Vol. CLXX, December 1934] It is strange what time does to political causes. A generation ago it seemed to many American conservatives as if the opinions which Emma Goldman was expressing might sweep the world. Now she fights almost alone for what seems to be a lost cause; contemporary radicals are overwhelmingly opposed to her; more than that, her devotion to liberty and her detestation of government interference might be regarded as placing her anomalously in the same part of the political spectrum as the gentlemen of the Liberty League, only in a more extreme position at its edge. Yet in this article, which might be regarded as her last will and testament, she sticks to her guns. Needless to say, her opinions are not ours. We offer them as an exhibit of valiant consistency, of really rugged individualism unaltered by opposition or by advancing age. --The Editors. How much a personal philosophy is a matter of temperament and how much it results from experience is a moot question. Naturally we arrive at conclusions in the light of our experience, through the application of a process we call reasoning to the facts observed in the events of our lives. The child is susceptible to fantasy. At the same time he sees life more truly in some respects than his elders do as he becomes conscious of his surroundings. He has not yet become absorbed by the customs and prejudices which make up the largest part of what passes for thinking. -

Contesting Tradition and Combating Intolerance a History of Free Thought in Kansas

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Fall 2000 Contesting Tradition And Combating Intolerance A History Of Free thought In Kansas Aaron K. Ketchell University of Kansas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Ketchell, Aaron K., "Contesting Tradition And Combating Intolerance A History Of Free thought In Kansas" (2000). Great Plains Quarterly. 2129. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CONTESTING TRADITION AND COMBATING INTOLERANCE A HISTORY OF FREETHOUGHT IN KANSAS AARON K. KETCHELL Diversity is the hallmark of freethought in Although the attitudes of freethinkers toward Kansas, for freethinkers were never a homoge religion are the primary concern of this essay, neous body. The movement was not only reli it must be remembered that freethinkers had gious, or for that matter, antireligious, different ideas about what the movement although the majority of social and political meant and that opposition to organized reli issues that it addressed had religious ground gion was only one, but a crucial element of the ing. No one specific organized group domi freethought agenda. nated historical Kansas freethinking. Instead, In order to understand the history of individuals in the form of editors of various freethought in Kansas one must first define newspapers, journals, and book series became the movement and its ideology. -

Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy

Brill’s Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy Edited by Nathan Jun LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Editor’s Preface ix Acknowledgments xix About the Contributors xx Anarchism and Philosophy: A Critical Introduction 1 Nathan Jun 1 Anarchism and Aesthetics 39 Allan Antliff 2 Anarchism and Liberalism 51 Bruce Buchan 3 Anarchism and Markets 81 Kevin Carson 4 Anarchism and Religion 120 Alexandre Christoyannopoulos and Lara Apps 5 Anarchism and Pacifism 152 Andrew Fiala 6 Anarchism and Moral Philosophy 171 Benjamin Franks 7 Anarchism and Nationalism 196 Uri Gordon 8 Anarchism and Sexuality 216 Sandra Jeppesen and Holly Nazar 9 Anarchism and Feminism 253 Ruth Kinna For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV viii CONTENTS 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism 285 Roderick T. Long 11 Anarchism, Poststructuralism, and Contemporary European Philosophy 318 Todd May 12 Anarchism and Analytic Philosophy 341 Paul McLaughlin 13 Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy 369 Brian Morris 14 Anarchism and Psychoanalysis 401 Saul Newman 15 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century European Philosophy 434 Pablo Abufom Silva and Alex Prichard 16 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought 454 Crispin Sartwell 17 Anarchism and Phenomenology 484 Joeri Schrijvers 18 Anarchism and Marxism 505 Lucien van der Walt 19 Anarchism and Existentialism 559 Shane Wahl Index of Proper Names 583 For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV CHAPTER 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism Roderick T. Long Introduction -

Libertarian Feminism: Can This Marriage Be Saved? Roderick Long Charles Johnson 27 December 2004

Libertarian Feminism: Can This Marriage Be Saved? Roderick Long Charles Johnson 27 December 2004 Let's start with what this essay will do, and what it will not. We are both convinced of, and this essay will take more or less for granted, that the political traditions of libertarianism and feminism are both in the main correct, insightful, and of the first importance in any struggle to build a just, free, and compassionate society. We do not intend to try to justify the import of either tradition on the other's terms, nor prove the correctness or insightfulness of the non- aggression principle, the libertarian critique of state coercion, the reality and pervasiveness of male violence and discrimination against women, or the feminist critique of patriarchy. Those are important conversations to have, but we won't have them here; they are better found in the foundational works that have already been written within the feminist and libertarian traditions. The aim here is not to set down doctrine or refute heresy; it's to get clear on how to reconcile commitments to both libertarianism and feminism—although in reconciling them we may remove some of the reasons that people have had for resisting libertarian or feminist conclusions. Libertarianism and feminism, when they have encountered each other, have most often taken each other for polar opposites. Many 20th century libertarians have dismissed or attacked feminism—when they have addressed it at all—as just another wing of Left-wing statism; many feminists have dismissed or attacked libertarianism—when they have addressed it at all—as either Angry White Male reaction or an extreme faction of the ideology of the liberal capitalist state.