ACCF/AHA 2011 Expert Consensus Document on Hypertension in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypertension – Adult – Clinical Practice Guideline

Hypertension – Adult – Clinical Practice Guideline Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 3 SCOPE ...................................................................................................................................... 4 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................................................. 5 Establish the Diagnosis ........................................................................................... 5 Patient Evaluation ................................................................................................... 7 Treatment Goals ..................................................................................................... 7 Lifestyle Modifications ............................................................................................. 8 Table 4 – Lifestyle Modifications ........................................................................ 9 Medication Treatment............................................................................................ 11 Figure 1 - Initiation and Titration of Antihypertensive Medication ..................... 13 Table 7 - Antihypertensive -

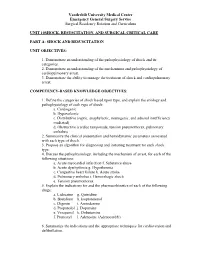

Unit 10 Shock,Resuscitation Part A

Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum UNIT 10SHOCK, RESUSCITATION, AND SURGICAL CRITICAL CARE PART A: SHOCK AND RESUSCITATION UNIT OBJECTIVES: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the pathophysiology of shock and its categories. 2. Demonstrate an understanding of the mechanisms and pathophysiology of cardiopulmonary arrest. 3. Demonstrate the ability to manage the treatment of shock and cardiopulmonary arrest. COMPETENCY-BASED KNOWLEDGE OBJECTIVES: 1. Define the categories of shock based upon type, and explain the etiology and pathophysiology of each type of shock: a. Cardiogenic b. Hypovolemic c. Distributive (septic, anaphylactic, neurogenic, and adrenal insufficiency mediated) d. Obstructive (cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus) 2. Summarize the clinical presentation and hemodynamic parameters associated with each type of shock. 3. Propose an algorithm for diagnosing and initiating treatment for each shock type. 4. Discuss the pathophysiology, including the mechanism of arrest, for each of the following situations: a. Acute myocardial infarction f. Substance abuse b. Acute dysrhythmia g. Hypothermia c. Congestive heart failure h. Acute stroke d. Pulmonary embolus i. Hemorrhagic shock e. Tension pneumothorax 5. Explain the indications for and the pharmacokinetics of each of the following drugs: a. Lidocaine g. Quinidine b. Bretylium h. Isoproterenol c. Digoxin i. Amiodarone d. Propanolol j. Dopamine e. Verapamil k. Dobutamine f. Pronestyl l. Adenosine (Adenocard®) 6. Summarize the indications and the appropriate techniques for cardioversion and defibrillation. Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum 7. Outline the signs and symptoms of acute airway obstruction and define the appropriate intervention in adult and pediatric patients. -

A Case Report of Takotsubo Syndrome Complicated by Ischaemic Stroke: the Clinical Dilemma of Anticoagulation

European Heart Journal - Case Reports CASE REPORT doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytab051 Other A case report of takotsubo syndrome complicated by ischaemic stroke: the clinical dilemma of anticoagulation Giuseppe Iuliano 1, Rosa Napoletano2, Carmine Vecchione 1,3, and Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ehjcr/article/5/3/ytab051/6170700 by guest on 01 October 2021 Rodolfo Citro 1* 1Cardiothoracic and Vascular Department, Cardiology Unit, University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona”, Heart Tower—Room 807, Largo Citta` d’Ippocrate, 84131 Salerno, Italy;; 2Neurology Department, Stroke Unit, University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona”, Largo Citta` d’Ippocrate, 84131 Salerno, Italy; and 3Vascular Pathophysiology Unit, IRCCS Neuromed, Via Atinense, 18, 86077 Pozzilli, Isernia, Italy Received 2 September 2020; first decision 22 October 2020; accepted 28 January 2021 For the podcast associated with this article, please visit https://academic.oup.com/ehjcr/pages/podcast Background Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is an acute and transient heart failure syndrome due to reversible myocardial dysfunc- tion characterized by a wide spectrum of possible clinical scenarios. About one-fifth of TTS patients experience ad- verse in-hospital events. Thromboembolic complications, especially stroke, have been reported, albeit in a minority of patients. ................................................................................................................................................................................................... Case summary A 69-year-old woman presented to our emergency department for dyspnoea after a family quarrel. Electrocardiogram revealed ST-segment elevation in anterolateral leads and laboratory exams showed a slight ele- vation of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin. The patient was treated according to current guidelines on ST-elevation myocardial infarction and referred to the cath lab. Urgent coronary angiography revealed normal coronary arteries. -

Heart Sound Classification for Murmur Abnormality Detection Using an Ensemble Approach Based on Traditional Classifiers and Feature Sets

Anatolian Journal of Computer Sciences Volume:5 No:1 2020 © Anatolian Science pp:1-13 ISSN:2548-1304 Heart Sound Classification for Murmur Abnormality Detection Using an Ensemble Approach Based on Traditional Classifiers and Feature Sets Ali Fatih Gündüz1*, Ali Karcı2 *1Akçadağ Voc. Highschool, Malatya Turgut Ozal Uni., Malatya, Turkey ([email protected]) 2Department of Computer Eng., Inonu University, Malatya, Turkey, ([email protected]) Received Date: Jan. 7, 2020. Acceptance Date: Mar. 21, 2020. Published Date : Jun. 1, 2020. Abstract— Phonocardiography (PCG) is a method based on examination of mechanical sounds coming from heart during its regular contraction/relaxation activities such as opening and closing of the valves and blood turbulence towards vessels and heart chambers. Today there are high technology tools to record those sounds in electronic environment and enable us to analyze them in detail. The constraints such as human’s limited audible range, environment noise and inexperience of physicians can be overcome by the use of those tools and development of state-of-art signal processing and machine learning methods. In this study we examined heart sounds and classified them as normal or abnormal focusing on the efficiency of ensemble classifiers. Features of heart sounds are extracted by using Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) and time-domain morphological characteristics of the signals. As a novel contribution, Karcı entropy is derived from DWT of PCG signals and used for the first time as feature in heart sound classification. K-Nearest Neighbor (kNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) classifiers and their ensembles are used as classifiers. -

MIT Automated Auscultation System By

MIT Automated Auscultation System by Zeeshan Hassan Syed S.B., Computer Science and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2003) Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2003 @Zeeshan H. Syed, MMIII. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and publicly distribute paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. MASSACHUSETTS INSTiTUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 2 0 2004 LIBRARIES A uthor . ...................... o lectrical Engineering and Computer Science May 9, 2003 Certified by... .. ....... John V. Guttag Professor, ComDuter Science and Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by........... Arthur C. Smith Chairman, Department Uommittee on Graduate Theses BARKER 2 MIT Automated Auscultation System by Zeeshan Hassan Syed S.B., Computer Science and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2003) Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on May 9, 2003, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Abstract At every annual exam, the primary care physician uses a stethoscope to listen for cardiac abnormalities. This approach is non-invasive, inexpensive, and fast. It is also highly unreliable. Over 80% of the people referred to cardiologists as suffering from the most commonly diagnosed condition, mitral valve prolapse (MVP), do not have this condition. Working in conjunction with cardiologists at MGH, we developed a robust, low cost, easy to use tool that can be employed to diagnose MVP in the office of pri- mary care physicians. -

Complex Hypertension

COMPLEX HYPERTENSION Anita Ralstin, FNP-BC Next Step Health Consultant, LLC Incidence Of Hypertension ¨ About 70 million American adults have high blood pressure. About 33% of the population ¨ Only 52% have BP under control. ¨ Nearly a third of US adults have prehypertension. ¨ Hypertension costs $46 billion a year. (healthcare services, medications, missed work) From CDC Blood Pressure Facts 2015 What is Hypertension? ¨ JNC 7 (1997) definitions Stages Systolic Diastolic Prehypertension 102-129 OR 80-89 High BP Stage 1 140-159 OR 90-99 High BP Stage 2 160 or higher OR 100 or higher ¨ JNC 7 Goal BP = <140/90 ¨ JNC 8: did not define classification ¤ Patients 60 and +, start Rx when BP > 150/90* ¤ Patient < 60, start Rx when BP > 140/80 From National Heart, Lung Blood Institute SPRINT Study ¨ NIH supported study ¨ 9000+ subjects ¨ With at least one risk factor for CV disease ¨ Preliminary findings--- ¨ Adults 50 and older with HBP, targeting a SBP <120 reduced rates of CV events by 25%; reduced risk of death by 27% compared to a target of SBP 140. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Complex/Resistant Hypertension ¨ Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that remains above goal despite concurrent use of three antihypertensive agents of different classes, one of which should be a diuretic. ¨ Patients whose blood pressure is controlled with four or more medications are considered to have resistant hypertension. Complex Hypertension ¨ BP above goal- 140/90 most patients. 130/80 diabetics or renal disease. ¨ Confirmed on at least two occasions with appropriate size cuff. ¨ Adherence to appropriate 3 drug regiment including a diuretic. -

Initial Approach to Hypertension in the Hemodynamics Unit: Review Article

REVIEW ARTICLE Initial approach to hypertension in the hemodynamics unit: review article Abordagem inicial da hipertensão arterial sistêmica em unidade de hemodinâmica: artigo de revisão Gustavo Teixeira Fulton Schimit1, José Manoel da Silva Silvestre2, Wander Eduardo Sardinha2, Eduardo Durante Ramires2, Domingos de Morais Filho2, Guilon Otávio Santos Tenório1, Fernando Barbosa Trevisan1 Abstract Correct identification and early management of hypertensive disorders should be a part of the therapeutic repertoire of every professional working in hemodynamics units. Based on recent publications, this study aims to propose a practical approach to the identification and early management of these disorders in this type of service. Keywords: hypertension; blood pressure; therapeutics; antihypertensive agents. Resumo O reconhecimento correto e manejo inicial das síndromes hipertensivas devem fazer parte do arsenal terapêutico de todo profissional que trabalhe em unidade de hemodinâmica. Este trabalho tem por objetivo, baseado em publicações recentes, propor uma abordagem prática para identificação e manejo inicial destes agravos nessa unidade. Palavras-chave: hipertensão; pressão arterial; terapêutica; anti-hipertensivos. 1Hospital Universitário Regional do Norte do Paraná, Londrina, PR, Brazil. 2Departamento de Clínica Cirúrgica, Universidade Estadual de Londrina – UEL, Londrina, PR, Brazil. Conflict of interest: No conflicts of interest declared concerning the publication of this article. Submitted on: 01.21.12. Accepted on: 03.25.13. The study was carried out at Hospital Universitário da Universidade Estadual de Londrina – UEL, Londrina, PR, Brazil. J Vasc Bras. 2013 Jun; 12(2):133-138 133 Hypertension in the hemodynamics unit INTRODUCTION been objectively adopted for the definition of normal Constant technical advances in the profession, blood pressure, and increases of 20/10 mm Hg above as well as in materials and new technologies, have this level double the risk of cardiovascular diseases11. -

Ministry of Health of Ukraine Kharkiv National Medical University

Ministry of Health of Ukraine Kharkiv National Medical University AUSCULTATION OF THE HEART. NORMAL HEART SOUNDS, REDUPLICATION OF THE SOUNDS, ADDITIONAL SOUNDS (TRIPLE RHYTHM, GALLOP RHYTHM), ORGANIC AND FUNCTIONAL HEART MURMURS Methodical instructions for students Рекомендовано Ученым советом ХНМУ Протокол №__от_______2017 г. Kharkiv KhNMU 2017 Auscultation of the heart. normal heart sounds, reduplication of the sounds, additional sounds (triple rhythm, gallop rhythm), organic and functional heart murmurs / Authors: Т.V. Ashcheulova, O.M. Kovalyova, O.V. Honchar. – Kharkiv: KhNMU, 2017. – 20 с. Authors: Т.V. Ashcheulova O.M. Kovalyova O.V. Honchar AUSCULTATION OF THE HEART To understand the underlying mechanisms contributing to the cardiac tones formation, it is necessary to remember the sequence of myocardial and valvular action during the cardiac cycle. During ventricular systole: 1. Asynchronous contraction, when separate areas of myocardial wall start to contract and intraventricular pressure rises. 2. Isometric contraction, when the main part of the ventricular myocardium contracts, atrioventricular valves close, and intraventricular pressure significantly increases. 3. The ejection phase, when the intraventricular pressure reaches the pressure in the main vessels, and the semilunar valves open. During diastole (ventricular relaxation): 1. Closure of semilunar valves. 2. Isometric relaxation – initial relaxation of ventricular myocardium, with atrioventricular and semilunar valves closed, until the pressure in the ventricles becomes lower than in the atria. 3. Phases of fast and slow ventricular filling - atrioventricular valves open and blood flows from the atria to the ventricles. 4. Atrial systole, after which cardiac cycle repeats again. The noise produced By a working heart is called heart sounds. In auscultation two sounds can be well heard in healthy subjects: the first sound (S1), which is produced during systole, and the second sound (S2), which occurs during diastole. -

Accidental Heart Murmurs Doi: 10.5455/Medarh.2017.71.284-287 Edin Begic1, Zijo Begic2 MED ARCH

REVIEW Accidental Heart Murmurs doi: 10.5455/medarh.2017.71.284-287 Edin Begic1, Zijo Begic2 MED ARCH. 2017 AUG; 71(4): 284-287 RECEIVED: JUN 20, 2017 | ACCEPTED: AUG 01, 2017 ABSTRACT Introduction: Accidental murmurs occur in anatomically and physiologically normal heart. Ac- cidental (innocent) murmurs have their own clearly defined clinical characteristics (asymp- tomatic, they require minimal follow-up care). Aim: To point out the significance of ausculta- 1Faculty of Medicine, Sarajevo School of Science and tion of the heart in the differentiation of heart murmurs and show clinical characteristics of Technology, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina accidental heart murmurs. Material and methods: Article presents review of literature which 2Pediatric Clinic, University Clinical Center Sarajevo, deals with the issue of accidental heart murmurs in the pediatric cardiology. Results: In the Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina group of accidental murmurs we include classic vibratory parasternal-precordial Stills mur- mur, pulmonary ejection murmur, the systolic murmur of pulmonary flow in neonates, venous Corresponding author: Edin Begic, MD. Faculty of hum, carotid bruit, Potaine murmur, benign cephalic murmur and mammary souffle. Con- Medicine, Sarajevo School of Science and Technology, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. ORCID ID: http:// clusion: Accidental heart murmurs are revealed by auscultation in over 50% of children and www.orcid.org/0000-0001-6842-262X. E-mail: youth, with a peak occurrence between 3-6 years or 8-12 years of life. Reducing the frequency [email protected]. of murmurs in the later period can be related to poor conduction of the murmur, although the disappearance of murmur in principle is not expected. -

6-Heart Sounds.Pdf

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM HEART SOUNDS Dr Syed Shahid Habib MBBS DSDM PGDCR FCPS Professor & Consultant Clinical Neurophysiology Dept. of Physiology College of Medicine & KKUH King Saud University PROF. HABIB 2018 OBJECTIVES At the end of the lecture you should be able to ….. 1. Enumerate the different heart sounds 2. Describe the cause and characteristic features of first and second heart sound 3. Correlate the heart sounds with different phases of cardiac cycle 4. Define murmurs and their clinical importance PROF. HABIB 2018 HEART SOUNDS D U P L U B B L U B B Heart sounds PROF. HABIB 2018 BEST HEARD AT 4 AREAS OF AUSCULTATION AREAS: ■ Pulmonary area: • 2nd Lt intercostal space ■ Aortic area: • 2nd Rt costal cartilage ■ Mitral area: • 5nd Lt intercostal space crossing mid- clavicular line, or • 9cm (2.5-3 in) from sternum ■ Tricuspid area: • lower part of sternum towards Rt side PROF. HABIB 2018 PROF. HABIB 2018 The Events of the Cardiac Cycle HEART SOUNDS • There are four heart sounds SI, S2, S3 & S4. • Two heart sound are audible with stethoscope S1 & S2 (Lub - Dub). • S3 & S4 are not audible with stethoscope Under normal conditions because they are low frequency sounds. • Ventricular Systole is between First and second Heart sound. • Ventricular diastole is between Second and First heart sounds. PROF. HABIB 2018 FIRST HEART SOUND (S1) • It is produced due to the closure of Atrioventricular valves (Mitral & Tricuspid) • It occurs at the beginning of the systole and sounds like LUB (beginning of the ‘isometric contraction’ phase) • Frequency: 25-45 Hz • Time: 0.15 sec • Its is heavier when compared to the 2nd heart sound. -

3 Blood Pressure and Its Measurement

Chapter 3 / Blood Pressure and Its Measurement 49 3 Blood Pressure and Its Measurement CONTENTS PHYSIOLOGY OF BLOOD FLOW AND BLOOD PRESSURE PHYSIOLOGY OF BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENT POINTS TO REMEMBER WHEN MEASURING BLOOD PRESSURE FACTORS THAT AFFECT BLOOD PRESSURE READINGS INTERPRETATION OF BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENTS USE OF BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENT IN SPECIAL CLINICAL SITUATIONS REFERENCES PHYSIOLOGY OF BLOOD FLOW AND BLOOD PRESSURE The purpose of the arterial system is to provide oxygenated blood to the tissues by converting the intermittent cardiac output into a continuous capillary flow and this is achieved by the structural organization of the arterial system. The blood flow in a vessel is basically determined by two factors: 1. The pressure difference between the two ends of the vessel, which provides the driving force for the flow 2. The impediment to flow, which is essentially the vascular resistance This can be expressed by the following formula: 6P Q = R where Q is the flow, 6P is the pressure difference, and R is the resistance. The pressure head in the aorta and the large arteries is provided by the pumping action of the left ventricle ejecting blood with each systole. The arterial pressure peaks in systole and tends to fall during diastole. Briefly, the peak systolic pressure achieved is determined by (see Chapter 2): 1. The momentum of ejection (the stroke volume, the velocity of ejection, which in turn are related to the contractility of the ventricle and the afterload) 2. The distensibility of the proximal arterial system 3. The timing and amplitude of the reflected pressure wave When the arterial system is stiff, as in the elderly, for the same amount of stroke output, the peak systolic pressure achieved will be higher. -

Hypertension Core Curriculum. Final.Indd

MICHIGAN HYPERTENSION CORE CURRICULUM Education modules for training and updating physicians and other health professionals in hypertension detection, treatment and control Developed by the Hypertension Expert Group A Partnership of the National Kidney Foundation of Michigan and the Michigan Department of Community Health 2010 Michigan Hypertension Core Curriculum 2010 Developed by the Hypertension Expert Group A Partnership of the National Kidney Foundation of Michigan and the Michigan Department of Community Health 2 Hypertension Core Curriculum NKFM & MDCH 3 Acknowledgements Hypertension Expert Workgroup Committee April 2010 Ziad Arabi, MD, Senior Staff Physician, Internal Medicine/Hospitalist Medicine, Henry Ford Hospital, Certified Physician Specialist in Clinical Hypertension* Dear Colleague: Aaref Badshah, MD, Chief Medical Resident, Department of Internal Medicine Saint Joseph Mercy-Oakland Hospital * In 2005, the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH) and the National Kidney Foundation of Michigan (NKFM) convened a group of hypertension experts to identify strategies that will improve Jason I Biederman DO, FACOI FASN, Hypertension Nephrology Associates, PC* blood pressure control in Michigan. Participants included physicians from across Michigan specializing Joseph Blount, MD, MPH, FACP, Medical Director, OmniCare Health Plan, Detroit, MI in clinical hypertension, leaders in academic research of hypertension and related disorders, and Mark Britton, MD, PhD, Center of Urban and African-American Health Executive Committee, Wayne representatives of key health care organizations that are addressing this condition that afflicts over 70 State University School of medicine, Wayne State University* million U.S. adults. The Hypertension Expert Group has focused on approaches to reduce the burden of kidney and cardiovascular diseases through more effective blood pressure treatment strategies.