ABSTRACT WHAT YOU DON't KNOW by Kärstin K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President to Veto Vets' Bonus Bill E1(»1T Are Killed, Over

VOL. LIIL, NO. 126. s.) MANCHESTER. CONN.. TUESDAY. FEBRUARY 27.1984. (T B N P A 6E 8) PRICE THREE CaUCH|^ PRESIDENT TO VETO Pastor’s Daughter Seized With Bandit Suq>ects ISAPFIADDED E1(»1T ARE KILLED, FORDEFENDDIG VETS’ BONUS BILL MHAILDEAL OVER 25 INJURED Makes First Ddbnte State STUDENTS’ BODIES Senate b retlig a ton ToU IN RAIL ACCIDENT ment on Snbject in Letter ARE SHIPPED HOME Tint PoBdeal Inflnence to Speaker Rainey— Vote PU-YI P R E P m Pennsylvania Train Leava and Personal Friaddiip Comes on March 12. College (Mfidals Advised FOR ENTHRONEMENT Tracks— Engine Plots Used to Obtain Contracts. Parents Not to Come to Down 20 Foot Embank WMhlngton, Feb. 27.— (AP)— The Preeldent's letter to Speaker Washington, Feb. 27.-^(AP)— Emperor of Manchokno To ment — Steel Coaches Rainey that he would veto the Pat Dartmonth. charges that “political influence man bonufl bill wga made public to and personal friendship were gener Be Principal Figure at Im- Keep On Moving, Knock day by the Speaker as follows: ally used” by airmail operators In "Memorandum for the Speaker: Hanover, N. H., Peb. 27.— (A P )— "Dear Henry: Men of Dartmouth today platmed a obtaining contracts during the Hoo pressve Rites Thursday. Down Two Story Signal "Mac has shown me your letter of farewell tribute to nine fellow stu ver administration, were laid before February twenty-first. Senate Investigators today by Karl “Naturally when I sugrgested to dents who were taken from them Tower and Wreck Three you that I could not approve the bill Simday by an invisible death. -

Music & Film Memorabilia

MUSIC & FILM MEMORABILIA Friday 11th September at 4pm On View Thursday 10th September 10am-7pm and from 9am on the morning of the sale Catalogue web site: WWW.LSK.CO.Uk Results available online approximately one hour following the sale Buyer’s Premium charged on all lots at 20% plus VAT Live bidding available through our website (3% plus VAT surcharge applies) Your contact at the saleroom is: Glenn Pearl [email protected] 01284 748 625 Image this page: 673 Chartered Surveyors Glenn Pearl – Music & Film Memorabilia specialist 01284 748 625 Land & Estate Agents Tel: Email: [email protected] 150 YEARS est. 1869 Auctioneers & Valuers www.lsk.co.uk C The first 91 lots of the auction are from the 506 collection of Jonathan Ruffle, a British Del Amitri, a presentation gold disc for the album writer, director and producer, who has Waking Hours, with photograph of the band and made TV and radio programmes for the plaque below “Presented to Jonathan Ruffle to BBC, ITV, and Channel 4. During his time as recognise sales in the United Kingdom of more a producer of the Radio 1 show from the than 100,000 copies of the A & M album mid-1980s-90s he collected the majority of “Waking Hours” 1990”, framed and glazed, 52 x 42cm. the lots on offer here. These include rare £50-80 vinyl, acetates, and Factory Records promotional items. The majority of the 507 vinyl lots being offered for sale in Mint or Aerosmith, a presentation CD for the album Get Near-Mint condition – with some having a Grip with plaque below “Presented to Jonathan never been played. -

Mike Royer INTERVIEW by PHIL BUSSE

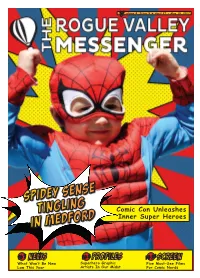

olume 4, Issue 9 H April 27 - May 10, 2017 Pg 7 Pg 8 Pg 26 2 / WWW.ROGUEVALLEYMESSENGER.COM Convergence: Digital Media and Technology On view through Saturday, May 27, 2017 Exhibition co-curated by Richard Herskowitz and Scott Malbaurn in collaboration with the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art and the Ashland Independent Film Festival. Works by Allison Cekala, Nina Katchadourian, Derek G. Larson, Ken Matsubara, Julia Oldham, Vanessa Renwick, Peter Sarkisian, and Lou Watson. First Friday Trolley May 5 Hours extended to 8 pm. Free and open to the public. Vanessa Renwick, Medusa Smack, 2012, MOV file, screen, rugs, pillows, 66 x 86 inches. On generous loan from the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Eugene, OR. This work was acquired with the assistance of The Ford Family Foundation through a special grant program managed by the Oregon Arts Commission. FREE Family Day Saturday, May 20 Photo: Mark Licari. 10 am to 1 pm. Free and open to the public. Gala Celebration: the Schneider Museum of Art at 30 Years Benefitting the Museum’s exhibitions and educational programming Please join our red carpet event as we celebrate our pearl anniversary SATURDAY, JUNE 10, 2017 AT 6:00 PM Cocktail hour with hors d’ouevres, open wine and beer bar on the patio An elegant dinner prepared by Larks Chef Damon Jones in the museum Silent art auction • Special entertainment Festive attire • Designated parking [email protected] or 541-552-8248 for invitation and ticket information mailing: 1250 Siskiyou Boulevard • gps: 555 Indiana Street Ashland, Oregon 97520 541-552-6245 • email: [email protected] web: sma.sou.edu • social: @schneidermoa PARKING: From Indiana Street, turn left into the metered lot between Frances Lane and Indiana St. -

US Apple LP Releases

Apple by the Numbers U.S. album releases From the collection of Andre Gardner of NY, NY SWBO‐101 The Beatles The Beatles Released: 22 Nov. 1968 (nicknamed "The White Album") In stark contrast to the cover to Sgt. Pepper's LHCB, the cover to this two record set was plain white, with writing only on the spine and in the upper right hand corner of the back cover (indicating that the album was in stereo). This was the first Beatles US album release which was not available in mono. The mono mix, available in the UK, Australia, and several other countries, sounds quite different from the stereo mix. The album title was embossed on the front cover. Inserts included a poster and four glossy pictures (one of each Beatle). The pictures were smaller in size than those issued with the UK album. A tissue paper separator was placed between the pictures and the record. Finally, as in every EMI country, the albums were numbered. In the USA, approximately 3,200,000 copies of the album were numbered. These albums were numbered at the different Capitol factories, and there are differences in the precise nature of the stamping used on the covers. Allegedly, twelve copies with east‐coast covers were made that number "A 0000001". SI = 2 ST 3350 Wonderwall Music George Harrison Released: 03 Dec. 1968 issued with an insert bearing a large Apple on one side. Normal Copy: SI = 2 "Left opening" US copy or copy with Capitol logo: SI = 7 T‐5001 Two Virgins John Lennon & Yoko Ono Released: January, 1969 (a.k.a. -

2015 Interview.Pdf

Interview from Spew, #87 February 2015 (originally published in abridged form) 2014’s triple disc behemoth Harshest Realm is the self-titled debut release of a musical project spearheaded by one Garret Kriston, a Chicago based musician whose formative years were split between formal studies and basement recording before toiling within the city’s DIY/punk scene. Now he has emerged with a sprawling document of what surely is a vast arsenal of artistic capabilities. Harshest Realm is now available via Coolatta Lounge CDs, along with fellow traveler Marshall Stacks’s latest jammers Lost in Sim City and the Snake Eyes/Point Blank single. ___________________________________________ Let’s start by giving the folks at home some background information. I’m particularly interested in learning how your relationship with music has developed over the years, so as to better understand where the music on the Harshest Realm album came from. No problem. I’m going to not hold back from rattling off influences and favorites, if that’s okay. Totally. The more the merrier. I was born at home on March 3rd, 1990 in Oak Park, down the street from Chicago’s west side, near Harlem between Harrison and Roosevelt. My earliest memory of music was seeing archival footage of The Beatles playing on the Ed Sullivan Show, which made playing guitar in a band and singing original songs seem like the most appealing activity in existence. I might have been two going on three, and I don’t remember much else from then besides puking in my crib and seeing carrots in it (the puke.) My older brother was discovering “classic rock,” so there were rock related bootleg VHS tapes in the house that would get played over and over. -

Recipe Collections

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut A special selection of Cooking Instruction – Recipe Collections – Low Fat & Healthy Cooking Slow Cooking – Grilling – Vegetarian Cooking – Ethnic Cooking – Regional & Exotic Cuisines Holidays & Entertaining – Cookies, Breads & Baking – Canning & Preserving – Wine Selection Notable Chefs & Restaurants – Bartending Guides and much more. June 28, 2019 6975267 1000 SAUCES, DIPS AND 7582633 THE QUINTESSENTIAL QUINOA DRESSINGS. By Nadia Arumugam. Provides the COOKBOOK. By Wendy Polisi. Discover new ways guidance, inspiration and recipes needed to lift to enjoy this South American staple with quinoa meals, desserts, snacks and more to new heights recipes for every occasion. Try Strawberry Spinach of deliciousness. Jazz up your meals with white Quinoa Salad, Quinoa Burgers, Almond Fudge sauces; brown stock-based sauces; pesto sauces; Quinoa Brownies, and more. Also gives alternatives creamy dips; fusion and Asian sauces; oil and for many recipes, covering the needs of vegan, vinegar dressings; salsas; and more. Color gluten-free, and sugar-free diners. Color photos. photos. 288 pages. Firefly. Pub. at $29.95 $5.95 221 pages. Skyhorse. Pub. at $17.95 $2.95 2878410 QUICK-FIX DINNERS. Ed. by the 6857833 100 RECIPES: The Absolute eds. of Southern Living. There’s something for Best Ways to Make the True Essentials. By everyone in this collection. Recipe flags show the eds. at America’s Test Kitchen. Organized busy cooks at a glance how long a dish takes from into three sections, each recipe is preceded by a start to finish. There are ideas for comfort foods thought provoking essay that positions the dish. pasta night, dinners, side dishes and desserts, You’ll find useful workday recipes like a killer proving that dinner made fast can be flavorful, tomato sauce; genius techniques for producing satisfying, and best of all, stress free. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/38 - Total : 1482 Vinyls Au 02/10/2021 Collection "Collection 1 Vinyl" De Jj26

Collection "Collection 1 vinyl" de jj26 Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 999 Lust Power And Money LP 130093 France Abrial (patrick Abrial) Vidéo LP AVC 130025 France Abrial Patrick (patrick Abrial... Chanson Pour Marie LP S63625 France Abrial Stratageme Group Same LP Inconnu Ac/dc Tnt LP Inconnu Ac/dc Powerage LP Inconnu Ac/dc Let There Be Rock LP Inconnu Ac/dc If You Want Blood You've Got I...LP Inconnu Ac/dc High Voltage LP Inconnu Ac/dc High Voltage LP Australie Ac/dc Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap LP Inconnu Ac/dc Back In Black LP Inconnu Accept Metal Heart LP Inconnu Accept I'm A Rebel LP Inconnu Ace Five A Side LP ANCL 2001 Royaume-Uni Adriano Celentano Tecadisk By Adriano Celentano LP Inconnu Aerosmith Toys In The Attic LP Inconnu Aerosmith Rocks LP Inconnu Aerosmith Live! Bootleg LP Inconnu Aerosmith Get Your Wings LP Inconnu Aerosmith Draw The Line LP Inconnu Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits LP Inconnu Aerosmith Aerosmith LP Inconnu Airbourne Black Dog Barking LP Inconnu Alabama The Closer You Get... LP Inconnu Alan White Ramshackled LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Zipper Catches Skin LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Welcome To My Nightmare LP Inconnu Alice Cooper School's Out LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Love It To Death LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Killer LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Easy Action LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Billion Dollar Babies LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Alice Cooper's Greatest Hits LP Inconnu Alien Cosmic Fantasy - 6 Song Ep LP Inconnu Alkatraz Doing A Moonlight By Alkatraz LP Inconnu Alphaville Afternoons In Utopia K7 Inconnu Alvin Lee -

Download the Newsletter

News and events for autumn/winter 2019 Berkshire | Buckinghamshire | Hampshire | Isle of Wight | London | Oxfordshire Snapping the Sixties Basildon Park en vogue Goat round-up Head to nationaltrust.org.uk/ – page 2 – page 3 – page 4 buckinghamshire (or substitute your own county name) for the highlights in your region From bright blooms to mellow views Behind every sunshine-hot September day hovers a wistful apprehension that this may be the last of the year. All the more reason to make the most of every single golden moment of late summer. Our places are a visual feast of vibrant Into autumn colour at this time of year. Dahlias have As the seasonal colour wheel turns, the had a big comeback in the last few years bright, rich flowers of late summer start and make a big impact at Hinton Ampner to fade in the planted beds just as the (Hampshire) with thousands of blooms autumn colour flushes through in the in shades of pretty pastels to hot sunset shrubs and trees. colours. The Vyne (Hampshire) also has eye-catching dahlias in its walled garden, Making the most of the mellow fruitfulness as does Mottistone (Isle of Wight). of the season with harvest events are Hughenden and Cliveden. Their autumn The parterres at Waddesdon, Hughenden celebrations with workshops, apple tastings, and Cliveden (Buckinghamshire) remain countryside crafts and gardeners top tips bold and bright all the way through to run throughout October until the end of September and it’s a wonderful time to half term. Greys Court (Oxfordshire) is catch the last of the colour and drink in the celebrating the traditions of the WI during views whilst the gardens are quieter. -

I Said, • How Can You Be a Buyer and Seller Both L

J'oliJ{·'rUllY. 103 ard March, 191 I said, • How can you be a buyer and seller majority of the growers, if not all Gf them, who both l' And he said, 'They are different tried tha.t co-operation, were very well satisfied. departments.' I said, "What does it mat My experience at Home was, that while it is a ter if there are fifty departments, if you are splendid idea, alId I think it will work well, that head of them a1l1' And he said, ' Our the growers at Home would send con&ignments managers come here and compete ill the open of one case, and two cases of one variety, with a market.' I said. (\-Vllo knocks down to particular mark on them. I suggest that no. them l' But I was so disgusted at the man's grower should send less than ten cases of one blindness to business ethics that I did not go variety and one grade. If a grower can send and any further." keep up to that, he maintains his individual 2642. Wllat do yon say regarding that 1~Wel1, interest, and the ten cases can be sold in the I went to the auctioneers, and questioned them market without expense and trouble; but consign about their stores, and their answer was that they ments of one, two, and three cases of Gne par sell the fruit consigned to them 011 the same com Mcular brand cause a good deal of tl'ouble as soon mission, and the grower gets the same results. -

Rememebering George 2014

1 2 Remembering George 2014 9AM 3 The Beatles - Long Long Long - The Beatles (Harrison) Lead vocal: George George, Paul and Ringo ran through 67 takes of George’s “Long Long Long,” then titled “It’s Been A Long Long Long Time,” on October 7, 1968. John Lennon was not at any of the sessions for the song. Harrison provided the lead vocal, accompanying himself on his Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar, Paul played Hammond organ, and Ringo played drums. George has said the “you” he is referring to in the song is God, and admits that the chords were taken from Bob Dylan’s “Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands,” which is on Dylan’s 1966 album “Blonde On Blonde.” Chris Thomas: “There’s a sound near the end of the song which is a bottle of Blue Nun wine rattling away on the top of a Leslie speaker cabinet. It just happened. Paul hit a certain note and the bottle started vibrating. We thought it was so good that we set the mikes up and did it again. The Beatles always took advantage of accidents.” The rattling sound is best heard in the right channel of the stereo version. George Harrison – Hear Me Lord - All Things Must Pass ‘70 Again written during the “Let It Be” sessions, this was the perfect ending to a master class of George Harrison compositions before entering the Apple Jam sessions. 9.13 BREAK George, tell us about the first song you ever wrote… 4 (Hit it) The Beatles - Don’t Bother Me – With The Beatles (Harrison) Lead vocal: George George Harrison’s first recorded original song. -

Where There Is a Will…

IF LIFE IS A GAME… THESE ARE THE STORIES True Stories by Real People Around the World About Being Human This book is dedicated to all people throughout the world who believe it is possible to live together in peace on this planet. Respect is the key that can help us transcend our differences and live in harmony. As we hold the vision, believe in the dream, and walk our talk, we will eventually evolve into peaceful people. It may take time, but it is possible, and we can never give up hope! CONTENTS Acknowledgements RULE ONE: YOU WILL RECEIVE A BODY When There Is a Will…There Is Always Some Way by Marilyn August (France) Learning to Fly by Janine Sheperd (Australia) A Letter for My Daughter by J. Nozipo Maraire (Zimbabwe) The Ultimate Gift by Bernard Lernout (Belgium) Mahaba by Keith Fleshman, M.D. (Ethiopia) Mr. Vijay Goel by Shubhra Agrawal (India) Facundo‘s Miracle by Pamela Daugavietis (Argentina) Nobuko by Lois Logan Horn (Japan) And the Beach Goes On by Tom Aspel (Israel) RULE TWO: YOU WILL BE PRESENTED WITH LESSONS Global Village by Donella Meadows and David Taub (Whole World) Human Family by Maya Angelou (United States) Going the Extra Mile by Bob Steevensz (The Netherlands) There Are No Bad Days by David Irvine (Canada) Transcending Fear by Elizabeth Zamerul Ally (Brazil) A Little Boy Who Inspired a Dream by Nkosi‘s Haven (South Africa) RULE THREE: THERE ARE NO MISTAKES, ONLY LESSONS There Are No Accidents by Nupur Sen (Pakistan) Values Passed On by Razzan Zahra (Syria) Alien Soldier by Gunter David (United States) Stop and Listen by Martha L. -

TC Mins 2014

Town Council Meeting #01-14 January 7, 1914 MINUTES FREEPORT TOWN COUNCIL MEETING #01-14 FREEPORT TOWN HALL COUNCIL CHAMBERS TUESDAY, JANUARY 7, 2014 – 6:30 P.M. FIRST ORDER OF BUSINESS: Pledge of Allegiance Everyone stood and recited the Pledge. SECOND ORDER OF BUSINESS: To waive the reading of the Minutes of Meeting #26-13 held on December 16, 2013 and to accept the Minutes as printed. MOVED AND SECONDED: To waive the reading of the Minutes of Meeting #26-13 held on December 16, 2013 and to accept the Minutes as printed. (DeGrandpre & Egan) VOTE: (7 Ayes) THIRD ORDER OF BUSINESS: Announcements Chair Hendricks announced that dog licenses expired on the 31st. There will be a Rabies Clinic at the Freeport Town Hall on January 11 from 9 a.m. to Noon. The storm date for the clinic is January 25th. For your convenience, the Town Clerk’s Office will be open for dog registrations at that time. A $25 late fee will be assessed on any dog not licensed by January 31. Licenses can also be obtained on line. The Circuit Breaker Program has been replaced by the Refundable Property Tax Credit that can be claimed on the Maine Individual Income Tax form. The new credit will become available January 2014 on the 2013 Maine Individual Income Tax form, 1040ME. For more information, contact Maine Revenue Services during normal work hours at 207 626-8475. Forms can be downloaded from the Maine Revenue Services' website- www.ME.gov/Revenue/forms or by calling 624-7894 to request that form be mailed to you.