Pain and Glory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sony Pictures Classics Acquires Pedro Almodóvar's Silencio

SONY PICTURES CLASSICS ACQUIRES PEDRO ALMODÓVAR’S SILENCIO Film marks tenth collaboration with the filmmaker and the Sony Pictures Classics team NEW YORK (June 9, 2015) – Sony Pictures Classics announced today that they have acquired North American rights to Pedro Almodóvar’s SILENCIO from El Deseo. Directed by Almodóvar and starring Adriana Ugarte, Emma Suárez, Daniel Grao, Dario Grandinetti, Inma Cuesta, Michelle Jenner, Rossy de Palma, SILENCIO charts the life of Julieta from 1985 to the present day. As she struggles to survive on the verge of madness, she finds her life is marked by a series of journeys revolving around the disappearance of her daughter. SILENCIO is about destiny, guilt and the unfathomable mystery that leads some people to abandon whom they love and about the pain that this brutal desertion provokes. The Sony Pictures Classics team has a long history with Almodóvar that began with WOMEN ON THE VERGE OF A NERVOUS BREAKDOWN at Orion Classics and has continued with eight films at SPC, including I’M SO EXCITED, THE SKIN I LIVE IN, BROKEN EMBRACES, VOLVER, BAD EDUCATION, ALL ABOUT MY MOTHER, TALK TO HER and THE FLOWER OF MY SECRET. SILENCIO marks Almodóvar’s 20th feature. In tandem with the 2006 release of VOLVER, Sony Pictures Classics also released VIVA PEDRO, the theatrical re-release of Almodóvar’s greatest films including WOMEN ON THE VERGE OF A NERVOUS BREAKDOWN, ALL ABOUT MY MOTHER, TALK TO HER, FLOWER OF MY SECRET, LIVE FLESH, LAW OF DESIRE, MATADOR and BAD EDUCATION. ABOUT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Michael Barker and Tom Bernard serve as co-presidents of Sony Pictures Classics— an autonomous division of Sony Pictures Entertainment they founded with Marcie Bloom in January 1992, which distributes, produces, and acquires independent films from around the world. -

October 18 - November 28, 2019 Your Movie! Now Serving!

Grab a Brew with October 18 - November 28, 2019 your Movie! Now Serving! 905-545-8888 • 177 SHERMAN AVE. N., HAMILTON ,ON • WWW.PLAYHOUSECINEMA.CA WINNER Highest Award! Atwood is Back at the Playhouse! Cannes Film Festival 2019! - Palme D’or New documentary gets up close & personal Tiff -3rd Runner - Up Audience Award! with Canada’ international literary star! This black comedy thriller is rated 100% on Rotten Tomatoes. Greed and class discrimination threaten the newly formed symbiotic re- MARGARET lationship between the wealthy Park family and the destitute Kim clan. ATWOOD: A Word After a Word “HHHH, “Parasite” is unquestionably one of the best films of the year.” After a Word is Power. - Brian Tellerico Rogerebert.com ONE WEEK! Nov 8-14 Playhouse hosting AGH Screenings! ‘Scorcese’s EPIC MOB PICTURE is HEADED to a Best Picture Win at Oscars!” - Peter Travers , Rolling Stone SE LAYHOU 2! AGH at P 27! Starts Nov 2 Oct 23- OPENS Nov 29th Scarlett Johansson Laura Dern Adam Driver Descriptions below are for films playing at BEETLEJUICE THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI Dir.Tim Burton • USA • 1988 • 91min • Rated PG. FEAT. THE VOC HARMONIC ORCHESTRA the Playhouse Cinema from October 18 2019, Dir. Paul Downs Colaizzo • USA • 2019 • 103min • Rated STC. through to and including November 28, 2019. TIM BURTON’S HAUNTED CLASSIC “Beetlejuice, directed by Tim Burton, is a ghost story from the LIVE MUSICAL ACCOMPANIMENT • CO-PRESENTED BY AGH haunters' perspective.The drearily happy Maitlands (Alec Baldwin and Iconic German Expressionist silent horror - routinely cited as one of Geena Davis) drive into the river, come up dead, and return to their the greatest films ever made - presented with live music accompani- Admission Prices beloved, quaint house as spooks intent on despatching the hideous ment by the VOC Silent Film Harmonic, from Kitchener-Waterloo. -

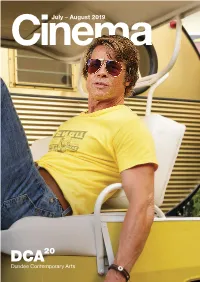

Cinema, on the Big Screen, with an Audience, Midsommar 6 Something That We Know Quentin Feels As Once Upon a Time In

CinJuly – Ae ugust 2019ma One of the most anticipated films of the summer, Contents Quentin Tarantino’s latest offering is a perfect New Films summer movie. Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood Blinded by the Light 9 o is full of energy, laughs, buddies and baddies, and The Chambermaid 8 the kind of bravado filmmaking we’ve come to love l The Dead Don’t Die 7 from this director. It is also, without a shadow of Ironstar: Summer Shorts 28 l a doubt, the kind of film that begs to be seen in The Lion King 27 a cinema, on the big screen, with an audience, Midsommar 6 something that we know Quentin feels as Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood 10 e passionately about as we do. It is a real thrill to Pain and Glory 11 be able to say Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood Photograph 8 will be shown at DCA exclusively on 35mm. We Robert the Bruce 5 can’t wait to fire up our Centurys, hear the whirr h Spider-Man: Far From Home 4 of the projectors in the booth and experience the Tell It To The Bees 7 magic of celluloid again. If you’ve never seen a film The Cure – Anniversary 13 on film, now is your chance! 197 8–2018 Live in Hyde Park Vita & Virginia 4 Another master of cinema, Pedro Almodóvar, also Documentary returns to our screens with an introspective, tender Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love 13 look at the life of an artist facing up to his regrets Of Fish and Foe 12 and the past loves who shaped him. -

Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2011 Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas Frans Weiser University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Weiser, Frans, "Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas" (2011). Open Access Dissertations. 347. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/347 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CON-SCRIPTING THE MASSES: FALSE DOCUMENTS AND HISTORICAL REVISIONISM IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation Presented by FRANS-STEPHEN WEISER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2011 Program of Comparative Literature © Copyright 2011 by Frans-Stephen Weiser All Rights Reserved CON-SCRIPTING THE MASSES: FALSE DOCUMENTS AND HISTORICAL REVISIONISM IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation Presented by FRANS-STEPHEN WEISER Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________________ David Lenson, Chair _______________________________________________ -

Anna Magnani

5 JUL 19 5 SEP 19 1 | 5 JUL 19 - 5 SEP 19 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT HOME OF THE EDINBURGH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Filmhouse, Summer 2019, Part II Luckily I referred to the last issue of this publication as the early summer double issue, which gives me the opportunity to call this one THE summer double issue, as once again we’ve been able to cram TWO MONTHS (July and August) of brilliant cinema into its pages. Honestly – and honesty about the films we show is one of the very cornerstones of what we do here at Filmhouse – should it become a decent summer weather-wise, please don’t let it put you off coming to the cinema, for that would be something of an, albeit minor in the grand scheme of things, travesty. Mind you, a quick look at the long-term forecast tells me you’re more likely to be in here hiding from the rain. Honestly…? No, I made that last bit up. I was at a world-renowned film festival on the south coast of France a few weeks back (where the weather was terrible!) seeing a great number of the films that will figure in our upcoming programmes. A good year at that festival invariably augurs well for a good year at this establishment and it’s safe to say 2019 was a very good year. Going some way to proving that statement right off the bat, one of my absolute favourites comes our way on 23 August, Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory which is simply 113 minutes of cinematic pleasure; and, for you, dear reader, I put myself through the utter bun-fight that was getting to see Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time.. -

Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian Video Introduction To

Virtual May 5, 2020 (XL:14) Pedro Almodóvar: PAIN AND GORY (2019, 113m) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian video introduction to this week’s film Click here to find the film online. (UB students received instructions how to view the film through UB’s library services.) Videos: “Pedro Almodóvar and Antonio Banderas on Pain and Glory (New York Film Festival, 45:00 min.) “How Antonio Banderas Became Pedro Almodóvar in ‘Pain & Glory’” (Variety, 4:40) “PAIN AND GLORY Cast & Crew Q&A” (TIFF 2019, 24:13) CAST Antonio Banderas...Salvador Mallo “Pedro Almodóvar on his new film ‘Pain and Glory, Penélope Cruz...Jacinta Mallo Penelope Cruz and his sexuality” (27:23) Raúl Arévalo...Venancio Mallo Leonardo Sbaraglia...Federico Delgado DIRECTOR Pedro Almodóvar Asier Etxeandia...Alberto Crespo WRITER Pedro Almodóvar Cecilia Roth...Zulema PRODUCERS Agustín Almodóvar, Ricardo Marco Pedro Casablanc...Doctor Galindo Budé, and Ignacio Salazar-Simpson Nora Navas...Mercedes CINEMATOGRAPHER José Luis Alcaine Susi Sánchez...Beata EDITOR Teresa Font Julieta Serrano...Jacinta Mallo (old age) MUSIC Alberto Iglesias Julián López...the Presenter Paqui Horcajo...Mercedes The film won Best Actor (Antonio Banderas) and Best Rosalía...Rosita Composer and was nominated for the Palme d'Or and Marisol Muriel...Mari the Queer Palm at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival. It César Vicente...Eduardo was also nominated for two Oscars at the 2020 Asier Flores...Salvador Mallo (child) Academy Awards (Best Performance by an Actor for Agustín Almodóvar...the priest Banderas and Best International Feature Film). -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Treasures from the Yale Film Archive

TREASURES FROM THE YALE FILM ARCHIVE SUNDAY AN ONGOING SERIES OF CLASSIC AND CONTEMPORARY FILMS PRESENTED IN 35MM BY THE YALE FILM STUDY CENTER SEPTEMBER 17, 2017 2:00PM • WHITNEY HUMANITIES CENTER PRESENTED WITH SUPPORT FROM VOLVERVOLVER PAUL L. JOSKOW ’70 M.PHIL., ’72 PH.D. All about mothers, Pedro Almodóvar’s 2006 quiet masterpiece blends tragedy, melodrama, magical realism, and farce in a story of three generations of working-class Spanish women and the secrets they carry between La Mancha and Madrid. Penélope Cruz o. gives the performance of her career as Raimunda, struggling to protect her teenage daughter (Yohana Cobo) while haunted by N the ghost of her estranged mother (Carmen Maura). A.O. Scott said of the film, “To relate the details of the narrative—death, cancer, S 1 E 4 betrayal, parental abandonment, more death—would create an impression of dreariness and woe. But nothing could be further from A S O N the spirit of VOLVER which is buoyant without being flip, and consoling without ever becoming maudlin.” One of Almodóvar’s most assured and mature works, it foregoes the flashy visuals and assertive soundtracks of his earlier comedies, as well as the complex plots of the dramas that immediately preceded it, TALK TO HER and BAD EDUCATION. Other than MATADOR and KIKA, it was his first film to be released in the U.S. under its untranslated Spanish title. Volver means return, and the many returns throughout the film help bring the characters and their director overdue resolutions to unfinished business from the past. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Vivat Academia ISSN: 1575-2844 Forum XXI Durán-Manso, Valeriano LOS RASGOS MELODRAMÁTICOS DE TENNESSEE WILLIAMS EN PEDRO ALMODÓVAR: ESTUDIO DE PERSONAJES DE LA LEY DEL DESEO, TACONES LEJANOS Y LA FLOR DE MI SECRETO Vivat Academia, no. 138, 2017, March-June, pp. 96-119 Forum XXI DOI: https://doi.org/doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.138.96-119 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=525754430006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Vivat Academia Revista de Comunicación · 15 Marzo-15 Junio 2017 · Nº 138 ISSN: 1575-2844 · pp 96-119 · http://dx.doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.138.96-119 RESEARCH Recibido: 11/06/2016 --- Aceptado: 04/12/2016 --- Publicado: 15/03/2017 THE MELODRAMATIC TRAITS OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS IN PEDRO ALMODÓVAR: STUDY OF CHARACTERS OF THE LAW OF DESIRE, HIGH HEELS AND THE FLOWER OF MY SECRET Valeriano Durán Manso1: University of Cádiz, Spain. [email protected] ABSTRACT The main film adaptations of the literary production of the American playwright Tennessee Williams premiered in 1950 through 1968, and they settled in the melodrama. These films contributed to the thematic evolution of Hollywood due to the gradual dissolution of the Hays Code of censorship and, furthermore, they determined the path of this genre toward more passionate and sordid aspects. Thus, A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, or Suddenly, Last Summer incorporated sexual or psychological issues through tormented characters that had not been previously dealt with in the cinema. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

The Decadent Image of the Journalist in Pedro Almodóvar Cinema

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación. March 15, 2019 / June 15, 2019 nº 146, 137-160 ISSN: 1575-2844 http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.146.137-160 RESEARCH Received: 12/01/2018 --- Accepted: 11/10/2018 --- Published: 15/03/2019 THE DECADENT IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN PEDRO ALMODÓVAR CINEMA La imagen decadente del periodista en el cine de Pedro Almodóvar Cristina San José de la Rosa1: University of Valladolid. Spain. [email protected] ABSTRACT Journalism and journalists play key roles in the cinema of Pedro Almodóvar. The director uses the character communicator with superficial presenters in most cases and occasionally precise serious informants. This study analyzes the presence of means of communication or journalists in his last 17 films and affects the prevalence of frivolity and satire before the camera as it is shown four emblematic titles to Ticos: Distant Heels (1991), Kika (1993) Talk to her (2002) and Return (2006). The data is extracted from the doctoral thesis The journalists in the Spanish cinema (1942-2012), in which the professional and personal profile of the informers which appear as protagonists or secondary in Spanish films is analyzed during the seventy years2. KEY WORDS: journalism – cinema – Almodóvar – gender – villains. RESUMEN Periodismo y periodistas juegan papeles clave en el cine de Pedro Almodóvar. El director emplea el personaje del comunicador con superficiales presentadoras en la mayoría de los casos y alguna vez puntual serios informadores. Este estudio analiza la presencia de medios de comunicación o periodistas en sus últimas 17 películas e incide 1Cristina San José de la Rosa: Licenciada en Ciencias de la Información por la Universidad Pontifica de Salamanca y licenciada en Filología Hispánica por la Universidad de Salamanca y la UNED. -

51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA

Northeast Modern Language Association 51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA Local Host: Boston University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo SUNY 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Carole Salmon | University of Massachusetts Lowell First Vice President Brandi So | Department of Online Learning, Touro College and University System Second Vice President Bernadette Wegenstein | Johns Hopkins University Past President Simona Wright | The College of New Jersey American and Anglophone Studies Director Benjamin Railton | Fitchburg State University British and Anglophone Studies Director Elaine Savory | The New School Comparative Literature Director Katherine Sugg | Central Connecticut State University Creative Writing, Publishing, and Editing Director Abby Bardi | Prince George’s Community College Cultural Studies and Media Studies Director Maria Matz | University of Massachusetts Lowell French and Francophone Studies Director Olivier Le Blond | University of North Georgia German Studies Director Alexander Pichugin | Rutgers, State University of New Jersey Italian Studies Director Emanuela Pecchioli | University at Buffalo, SUNY Pedagogy and Professionalism Director Maria Plochocki | City University of New York Spanish and Portuguese Studies Director Victoria L. Ketz | La Salle University CAITY Caucus President and Representative Francisco Delgado | Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY Diversity Caucus Representative Susmita Roye | Delaware State University Graduate Student Caucus Representative Christian Ylagan | University