From the Council to the Field: Navigating Mandates and Rules of Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 The first UN Infantry Battalion was deployed as part of United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-I). UN infantry soldiers march in to Port Said, Egypt, in December 1956 to assume operational responsibility. asdf ‘The United Nations Infantry Battalion is the backbone of United Nations peacekeeping, braving danger, helping suffering civilians and restoring stability across war-torn societies. We salute your powerful contribution and wish you great success in your life-saving work.’ BAN Ki-moon United Nations Secretary-General United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual ii Preface I am very pleased to introduce the United Nations Infantry Battalion Man- ual, a practical guide for commanders and their staff in peacekeeping oper- ations, as well as for the Member States, the United Nations Headquarters military and other planners. The ever-changing nature of peacekeeping operations with their diverse and complex challenges and threats demand the development of credible response mechanisms. In this context, the military components that are deployed in peacekeeping operations play a pivotal role in maintaining safety, security and stability in the mission area and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of each mission mandate. The Infantry Battalion con- stitutes the backbone of any peacekeeping -

Year in Review 2008

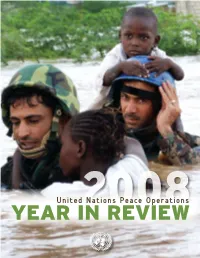

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

ITURI STAKES, ACTORS, DYNAMICS FEWER/AIP/APFO/CSVR would like to stress that this report is based on the situation observed and information collected between March and August 2003, mainly in Ituri and Kinshasa. The 'current' situation therefore refers to the circumstances that prevailed as of August 2003, when the mission last visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Agency. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish Government and its agencies. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Department for Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Finnish Government and its agencies. Copyright 2003 © Africa Initiative Program (AIP) Africa Peace Forum (APFO) Centre for Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) The views expressed by participants in the workshop are not necessarily those held by the workshop organisers and can in no way be take to reflect the views of AIP, APFO, CSVR and FEWER as organisations. 2 List of Acronyms............................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... -

Reputation As a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2019 Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2035 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, Organizations Law Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina. "Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations." Am. J. Int'l L. 113, no. 2 (2019): 221-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 by The American Society of International Law doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.122 REPUTATION AS A DISCIPLINARIAN OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS By Kristina Daugirdas* ABSTRACT As a disciplinarian of international organizations, reputation has serious shortcomings. Even though international organizations have strong incentives to maintain a good reputation, reputational concerns will sometimes fail to spur preventive or corrective action. Organizations have multiple audiences, so efforts to preserve a “good” reputation may pull organizations in many different directions, and steps taken to preserve a good reputation will not always be salutary. Recent incidents of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic illustrate these points. On April 29, 2015, The Guardian published an explosive story based on a leaked UN document.1 The document described allegations against French troops who had been deployed to the Central African Republic pursuant to a mandate established by the Security Council. -

Guidelines on Human Rights Education for Health Workers Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul

guidelines on human rights education for health workers Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul. Miodowa 10 00–251 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2013 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ ODIHR as the source. ISBN 978-92-9234-870-0 Designed by Homework, Warsaw, Poland Cover photograph by iStockphoto Printed in Poland by Sungraf Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................ 5 FOreworD ................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ............................................................................................11 Rationale for human rights education for health workers............................. 11 Key definitions for the guidelines .............................................................................14 Process for elaborating the guidelines ................................................................... 15 Anticipated users of the guidelines .......................................................................... 17 Purposes of the guidelines ........................................................................................... 17 Application of the guidelines ......................................................................................18 -

Human Rights International Ngos: a Critical Evaluation

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Contributions to Books Faculty Scholarship 2001 Human Rights International NGOs: A Critical Evaluation Makau Mutua University at Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/book_sections Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Makau Mutua, Human Rights International NGOs: A Critical Evaluation in NGOs and Human Rights: Promise and Performance 151 (Claude E. Welch, Jr., ed., University of Pennsylvania Press 2001) Copyright © 2001 University of pennsylvania Press. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of scholarly citation, none of this work may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. For information address the University of Pennsylvania Press, 3905 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions to Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 7 Human Rights International NGOs A Critical Evaluation Makau Mutua The human rights movement can be seen in variety of guises. It can be seen as a move ment for international justice or as a cultural project for "civilizing savage" cultures. -

Human Rights Organisations on 5 Continents

FIDH represents 164 human rights organisations on 5 continents FIDH - International Federation for Human Rights 17, passage de la Main-d’Or - 75011 Paris - France CCP Paris: 76 76 Z Tel: (33-1) 43 55 25 18 / Fax: (33-1) 43 55 18 80 www.fi dh.org ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Cover: © AFP/MOHAMMED ABED Egypt, 16 December 2011. 04 Our Fundamentals 06 164 member organisations 07 International Board 08 International Secretariat 10 Priority 1 Protect and support human rights defenders 15 Priority 2 Promote and protect women’s rights 19 Priority 3 Promote and protect migrants’ rights 24 Priority 4 Promote the administration of justice and the i ght against impunity 33 Priority 5 Strengthening respect for human rights in the context of globalisation 38 Priority 6 Mobilising the community of States 43 Priority 7 Support the respect for human rights and the rule of law in conl ict and emergency situations, or during political transition 44 > Asia 49 > Eastern Europe and Central Asia 54 > North Africa and Middle East 59 > Sub-Saharan Africa 64 > The Americas 68 Internal challenges 78 Financial report 2011 79 They support us Our Fundamentals Our mandate: Protect all rights Interaction: Local presence - global action The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) is an As a federal movement, FIDH operates on the basis of interac- international NGO. It defends all human rights - civil, political, tion with its member organisations. It ensures that FIDH merges economic, social and cultural - as contained in the Universal on-the-ground experience and knowledge with expertise in inter- Declaration of Human Rights. -

Reporting Principles

COMMON SECURITY AND DEFENCE POLICY EU BATTLEGROUPS Updated: January 2011 Battllegroups/07 Full operational capability in 2007 The European Union is a global actor, ready to undertake its share of responsibility for global security. With the introduction of the battlegroup concept, the Union formed a (further) military instrument at its disposal for early and rapid responses, when necessary. On 1 January 2007 the EU battlegroup concept reached full operational capability. Since that date, the EU is able to undertake, if so decided by the Council, two concurrent single-battlegroup-sized (about 1 500-strong) rapid response operations, including the ability to launch both operations nearly simultaneously. At the 1999 Helsinki European Council meeting, rapid response was identified as an important aspect of crisis management. As a result, the Helsinki Headline Goal 2003 assigned to member states the objective of being able to provide rapid response elements available and deployable at very high levels of readiness. Subsequently, an EU military rapid response concept was developed. In June 2003 the first autonomous EU-led military operation, Operation Artemis, was launched. It showed very successfully the EU's ability to operate with a rather small force at a significant distance from Brussels, in this case more than 6 000 km. Moreover, it also demonstrated the need for further development of rapid response capabilities. Subsequently, Operation Artemis became a reference model for the development of a battlegroup-sized rapid response capability. In 2004 the Headline Goal 2010 aimed for completion of the development of rapidly deployable battlegroups, including the identification of appropriate strategic lift, sustainability and disembarkation assets, by 2007. -

Finnish Defence Forces International Centre the Many Faces of Military

Finnish Defence Forces International Finnish Defence Forces Centre 2 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Edited by Mikaeli Langinvainio Finnish Defence Forces FINCENT Publication Series International Centre 1:2011 1 FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FINCENT PUBLICATION SERIES 1:2011 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field EDITED BY MIKAELI LANGINVAINIO FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE TUUSULA 2011 2 Mikaeli Langinvainio (ed.): The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Finnish Defence Forces International Centre FINCENT Publication Series 1:2011 Cover design: Harri Larinen Layout: Heidi Paananen/TKKK Copyright: Puolustusvoimat, Puolustusvoimien Kansainvälinen Keskus ISBN 978–951–25–2257–6 ISBN 978–951–25–2258–3 (PDF) ISSN 1797–8629 Printed in Finland Juvenens Print Oy Tampere 2011 3 Contents Jukka Tuononen Preface .............................................................................................5 Mikaeli Langinvainio Introduction .....................................................................................8 Mikko Laakkonen Military Crisis Management in the Next Decade (2020–2030) ..............................................................12 Antti Häikiö New Military and Civilian Training - What can they learn from each other? What should they learn together? And what must both learn? .....................................................................................20 Petteri Kurkinen Concept for the PfP Training -

Civil–Military Relations in Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo: a Case Study on Crisis Management in Complex Emergencies

Chapter 19 Civil–Military Relations in Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo: A Case Study on Crisis Management in Complex Emergencies Gudrun Van Pottelbergh The humanitarian crisis in Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo deteriorated again in the second half of 2008. In reaction, the international community agreed to send additional peacekeepers to stabilize the region. Supporters of the Congolese peace process agree that a military reaction alone will however not be sufficient. A stable future of the region requires a combined civil and military approach. This will also necessitate the continuous support of the international community for the Congolese peace process. The European Union and the United States are the two main players in terms of providing disaster management and thus also in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The European Union in particular has set- up several crisis management operations in the country. For the purpose of an efficient and combined effort in disaster relief, this study will investigate how different or similar these two players are in terms of crisis management mechanisms. The chapter concludes that the development of new crisis management mechanisms and the requirements for a sustainable solution in Kivu create an opportunity for all stakeholders described. Through establishing a high- level dialogue, the European Union and the United States could come up with a joint strategic and long- term approach covering all of their instru- ments in place to support the security reform in Kivu. It is especially in this niche of civilian and military cooperation within crisis management operations that may lay a key to finally bring peace and stability in the East of the Democratic Republic of Congo. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

REPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS in the PHILIPPINES a Field Guide for Journalists and Media Workers

REPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE PHILIPPINES A Field Guide for Journalists and Media Workers Red Batario Main Author and Editor Yvonne T. Chua Luz Rimban Ibarra C. Mateo Writers Rorie Fajardo Project Coordinator Alan Davis Foreword The publication of this guide was made possible with the support of the US Department of State through the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL) Copyright 2009 PHILIPPINE HUMAN RIGHTS REPORTING PROJECT Published by the Philippine Human Rights Reporting Project 4th Floor, FSS Bldg., 89 Scout Castor St., Barangay Laging Handa Quezon City 1103 Philippines All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher. Printed in Quezon City, Philippines National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Batario, Red Reporting Human Rights in the Philippines: A Field Guide for Journalists and Media Workers TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .......................................................................8 REPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS AS NEWS .............. 10 Covering and reporting human rights are often reduced to simplistic narratives of the struggle between good and evil that is then set on a stage where dramatic depictions of human despair become a sensational representation of the day’s headlines HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE NEWS MEDIA ............ 19 Why do journalists and the news media need to know human rights? What are human rights? What are ordinary rights? THE NEWS PROCESS............................................ 31 How to explore other ways of covering, developing and reporting human rights for newspapers, television, radio and on-line publications.