Local Finance Benchmarking Toolkit: Piloting and Lessons Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Working Paper No. WGSO-4/2007/6 Council 8 May 2007 ENGLISH ONLY ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY Ad Hoc Preparatory Working Group of Senior Officials “Environment for Europe” Fourth meeting Geneva, 30 May–1 June 2007 Item 2 (e) of the provisional agenda Provisional agenda for the Sixth Ministerial Conference “Environment for Europe” Capacity-building STRENGTHENING ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE IN THE EASTERN EUROPE, CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA THROUGH LOCAL ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION PROGRAMMES 1 Proposed category II document2 Submitted by the Regional Environmental Centers for the Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia 1 The text in this document is submitted as received from the authors. This is a draft document as of 21 April 2007. 2 Background documents (informational and analytical documents of direct relevance to the Conference agenda) submitted through the WGSO. Table of Contents Executive Summary Part I: Background A) Institutional Needs Addressed B) History of LEAPs in EECCA C) Relevance to Belgrade Conference D) Process for Preparing the Report Part II: Results to Date A) Strengthened Environmental Governance B) Improved Environmental Conditions C) Increased Long-Term Capacity Part III: Description of Activities A) Central Asia B) Moldova C) Russia D) South Caucasus Part IV: Lessons Learned and Future Directions A) Lessons Learned B) Future Directions C) Role of EECCA Regional Environmental Centers Attachment A: R E S O L U T I O N of International Conference “Local Environmental Action Plans: Experience and Achievements of EECCA RECs” Executive Summary Regional Environmental Centers (RECs) in Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia (EECCA) have promoted local environmental action programs (LEAPs) the last five years as a means of strengthening environmental governance at the local level. -

Coe/EU Eastern Partnership Programmatic

CoE/EU Eastern Partnership Programmatic Co-operation Framework (PCF) 2015-2017 Project on “Strengthening the efficiency, professionalism and accountability of the judiciary in the Republic of Moldova” Launching of the court coaching programme on implementation of CEPEJ tools in the pilot courts of the Republic of Moldova LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Date: 04 September 2015, 10:00 – 17:00 Venue: Complexul turistic “Vatra”, or. Vadul-lui-Vodă, Parcul Nistrean Name, Surname, Title 1. Mr Jose-Luis Herrero, Head of Council of Europe in Chisinau 2. Mr Leonid Antohi, Project Coordinator, Council of Europe 3. Mr Ivan Crnčec, CEPEJ member (Croatia) 4. Mr Frans Van Der Doelen, CEPEJ member (The Netherlands) 5. Mr Fotis Karayannopoulos, Lawyer, CEPEJ expert (Greece) 6. Mr Jaša Vrabec, National Correspondent to the CEPEJ (Slovenia) 7. Mr Ruslan Grebencea, Senior Project Officer, Council of Europe in Chisinau 8. Mr Dumitru Visterniceanu, Superior Council of Magistracy 9. Mrs Palanciuc Victoria, Administration of courts Division, Ministry of Justice 10. Mrs Vitu Natalia, Head of judicial statistics service within the Department of Justice Administration, Ministry of Justice 11. Ms Lilia Grimalschi, Head of Department of analysis and enforcement of ECtHR Judgments, Ministry of Justice 12. Mr Oleg Melniciuc, President of Riscani District Court 13. Mrs Zinaida Dumitrasco, Head of the Secretariat, Riscani District Court, mun. Chisinau 14. Mrs Mocan Natalia, Head of generalization and systematization of judicial practice Service, Riscani District Court 15. Ms Eugenia Parfeni, Head of Department for systematization, generalization of judicial practice and PR, Riscani District Court 16. Mr Dvurecenschii Evghenii, judge, Cahul Court of Appeal 17. Mrs Hantea Svetlana, Head of Secretariat, Cahul Court of Appeal 18. -

“Romanian Waters”, Head of River Basin Management Plans Office, Bucharest, Romania

NATIONAL ADMNISTRATION “ROMANIAN WATERS” Romania key input to the Second Assessment of Transboundary Rivers, Lakes and Groundwaters under the UNECE Water Convention Prut River Basin CORINA COSMINA BOSCORNEA, PhD National Administration “Romanian Waters ”, Head of River Basin Management Plans Office, Bucharest, Romania Ukraine - Kiev, 28 th April 2010 Second Assessment of Transboundary Rivers, Lakes and Romanian transboundary river basins Information about transboundary river basins: •Somes/Szamos, •Mures/Maros, •Crisuri, Tisza River •Banat, basin •Siret, •Prut, •Dobrogea-Litoral , •Arges-Vedea Danube •Banat River Basin •Buzau-Ialomita District •Jiu Romanian river basins Prut river basins in the Danube river basin district Prut river basin 1. General description of the Prut river basin The total Population Area in area of the Major density in the Shared the Character with an river basin transbound area in the countries country in average elevation in the ary river country km² (%) country (persons/km 2) upland character Romania, (Ukrainian 10,990 Ukraine and 27820 Prut Carpathians) and 55 (39.5%) Moldova lowland (lower reaches) • The Prut river basin is shared by Ukraine, Romania and Moldova Its source is in the Ukrainian Carpathians. Later, the Prut forms the border between Romania and Moldova. • The rivers Lapatnic, Drageste and Racovet are transboundary tributaries in the Prut sub-basin; they cross the Ukrainian- Moldavian border. • The Prut River’s major national tributaries are the rivers Cheremosh and Derelui, (Ukraine), Baseu, Jijia, -

Road Infrastructure Development of Moldova

Government of The Republic of Moldova Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure Road infrastructure development Chisinau 2017 1 … Road Infrastructure Road network Public roads 10537 km including: National roads 3670 km, including: Asphalt pavement 2973 km Concrete pavement 437 km Macadam 261 km Local roads 6867 km, Asphalt pavement 3064 km Concrete pavement 46 km Macadam 3756 km … 2 Legal framework in road sector • Transport and Logistic Strategy 2013 – 2022 approved by Government Decision nr. 827 from 28.10.2013; • National Strategy for road safety approved by Government Decision nr. 1214 from 27.12.2010; • Road Law nr. 509 from 22.06.1995; • Road fund Law nr. 720 from 02.02.1996 • Road safety Law nr. 131 from 07.06.2007 • Action Plan for implementing of National strategy for road safety approved by Government Decision nr. 972 from 21.12.2011 3 … Road Maintenance in the Republic of Moldova • The IFI’s support the rehabilitation of the road infrastructure EBRD, EIB – National Roads, WB-local roads. • The Government maintain the existing road assets. • The road maintenance is financed from the Road Fund. • The Road Fund is dedicated to maintain almost 3000km of national roads and over 6000 km of local roads • The road fund is part of the state budget . • The main strategic paper – Transport and Logistics Strategy 2013-2022. 4 … Road Infrastructure Road sector funding in 2000-2015, mil. MDL 1400 976 461 765 389 1200 1000 328 800 269 600 1140 1116 1025 1038 377 400 416 788 75 200 16 15 583 200 10 2 259 241 170 185 94 130 150 0 63 63 84 2000 -

The Republic of Moldova

The Republic of Moldova The National Agency for Energy Regulation ANRE Alexandr Pushkin Street, no. 52 / A, MD-2005 Chisinau, Tel: 022 852 901, [email protected],http://www.anre.md ADMINISTRATION COUNCIL DECISION no. _____ March 2, 2021 Chisinau on the provisional certification of the natural gas transmission system operator "Vestmoldtransgaz" LLC, IDNO 1014600024244, legal address: MD-2004, Chisinau municipality, Stefan cel Mare si Sfant Avenue, no.180, off. 515 According to the provisions of art. 36 of the Law no. 108 / 27.05.2016 on natural gas, based on the application no. 9532 of 05.11.2020 on the certification of "Vestmoldtransgaz" LLC according to the "ownership separation" model and the attached documents that are in line with the established requirements, submitted by the nominated transmission system operator, as well as the information provided by the Motivation Note on the certification of TSO „Vestmoldtransgaz” LLC, the Administration Council of the National Agency for Energy Regulation, DECIDES: 1. To provisionally certify the natural gas transmission system operator „Vestmoldtransgaz” LLC, IDNO 1014600024244, holder of the license Series AC no. 001338 issued on 06.01.2016 for the natural gas transmission activity, according to the “ownership separation” model. 2. The Licensing, Monitoring and Control Department shall notify the Energy Community Secretariat within 5 working days of this decision and shall send it the Motivation Note on the provisional certification of TSO "Vestmoldtransgaz" LLC, which was the basis for issuing -

The Jewish Cemetery of Ungheni Before 1917 Ungheni Was Part of the Bessarabia Gubernia of the Russian Empire

The Jewish Cemetery of Ungheni Before 1917 Ungheni was part of the Bessarabia gubernia of the Russian Empire. Now it is part of the Republic of Moldova. Еврейское Кладбище, Унгены, Молдова Final report, Yefim Kogan, November 25, 2015 First reading – Terry Lasky, second reading – Yefim Kogan The project was started by JewishGen, Bessarabia SIG in 2015. The photographing was organized and financed by Avner Yonai, photographs were done by residents of Moldova Maria Calin – a history teacher and Serj – a local photographer. The cemetery is part of the large town cemetery located on strada Alexandru cel Bun, and not far from the Prut River. View it on the Google map above. 1 997 Jews lived in Ungheni in 1897 from a total population of 1697. 48 Jewish businesses were in Ungheni in 1924 and 1390 Jews lived there in 1930. Town Ungheni within the map of the Republic of Moldova. See the nearby town of Iasi, Romania, also see capital Chisinau (Kishinev) to the East, Balti - to the North. According to the report “Jewish Heritage Sites and Monuments in Moldova”, created by the United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad, 2010, the Jewish section of the town cemetery was established in 1958, after the old Jewish cemetery in the town was closed and signs of it were demolished. It contains approximately 100 gravestones. The stones at the new cemetery are all in good condition. The cemetery has no regular caretaker, but the area is occasionally cleaned and cleared by local individuals. Vegetation overgrowth is only a seasonal problem. -

Medium Sized Project Proposal

0(',806,=('352-(&7352326$/ 5(48(67)25*())81',1* Public Disclosure Authorized FINANCING PLAN (US$) AGENCY’S PROJECT ID: 3 GEF PROJECT/COMPONENT GEFSEC PROJECT ID: COUNTRY: REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Project 972,920 PROJECT TITLE: RENEWABLE ENERGY FROM PDF A* 25,000 AGRICULTURAL WASTES (REAW) SUB-TOTAL GEF 997,920 GEF AGENCY: WORLD BANK CO-FINANCING** OTHER EXECUTING AGENCY (IES): CONSOLIDATED IBRD/IDA/IFC AGRICULTURAL PROJECTS MANAGEMENT Government 1,434,950 Bilateral DURATION: 3 YEARS NGOs GEF FOCAL AREA: CLIMATE CHANGE Others 219,388 GEF OPERATIONAL PROGRAM: OP # 6 Sub-Total Co-financing: 1,654,338 Public Disclosure Authorized GEF STRATEGIC PRIORITY: CC 4 Total Project Financing: 2,652,258 ESTIMATED STARTING DATE: MAY 2005 FINANCING FOR ASSOCIATED ACTIVITY MPLEMENTING GENCY EE I A F : $146,000 IF ANY: N/A * PDFA approved on 23.03.2004 ** Details provided in the Financing Section CONTRIBUTION TO KEY INDICATORS OF THE BUSINESS PLAN: The project will contribute to the established target for OP#6 by removing barriers for the use of renewable energy from agricultural wastes in Moldova, and will reduce high implementation costs of such energy technologies due to low-volume of replication. Public Disclosure Authorized RECORD OF ENDORSEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: Constantin Mihalescu, minister of Ministry of Environmental and Natural Date: 16 February 2005 Recourses of Moldova, GEF National Focal Point This proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review Criteria for a Medium-sized Project. Project Contact Person: Emilia Battaglini, ECA Regional Coordinator Tel. -

Serviciul Vamal

Republica Moldova SERVICIUL VAMAL ORDIN Nr. OSV449/2016 din 05.12.2016 cu privire la modificarea anexei nr.8 la Ordinul Serviciului Vamal nr.346-O din 24.12.2009 „Referitor la aprobarea Normelor tehnice privind imprimarea, utilizarea şi completarea declaraţiei vamale în detaliu” Publicat : 23.12.2016 în MONITORUL OFICIAL Nr. 459-471 art. 2145 Data intrării în vigoare Întru asigurarea executării Hotărîrii Guvernului Republicii Moldova ”Cu privire la aprobarea efectivului-limită și a Regulamentului Serviciului Vamal” nr. 04 din 02.01.2007, alin. (4) art. 9, alin. (2) art. 132 şi alin. (4) art. 175 din Codul vamal al Republicii Moldova, nr. 1149-XIV din 20.07.2000, ORDON: 1. Se modifică anexa nr. 8 la Ordinul Serviciului Vamal „Referitor la aprobarea Normelor tehnice privind imprimarea, utilizarea şi completarea declaraţiei vamale în detaliu.” nr. 346-O din 24.12.2009, care va avea următorul cuprins: Cod birou / Denumire birou / post vamal Localitatea limitrofă post vamal 1000 Nord 1010 COSTEȘTI (PVFI, rutier) STÎNCA 1020 LIPCANI (PVFI, rutier) RĂDĂUȚI PRUT 1030 CRIVA1 (PVFI, rutier) MAMALIGA 1040 CRIVA2 (PVFI, feroviar) MAMALIGA 1050 LARGA1 (PVFI, rutier) KELMENȚI 1060 LARGA2 (PVFI, feroviar) KELMENȚI 1070 BRICENI (PVFI, rutier) ROSOȘANI 1080 GRIMĂNCĂUȚI (PVFS, rutier) VASKIVȚI 1090 OCNIȚA1 (PVFI, feroviar) SOKIREANÎ 1100 OCNIȚA2 (PVFI, rutier) SOKIREANÎ 1110 VOLCINEȚ (PVFI, feroviar) MOGHILIOV-PODOLISK 1120 OTACI (PVFI, rutier) MOGHILIOV-PODOLISK 1130 UNGURI (PVFL, rutier) BRONNIȚA 1140 COSĂUȚI (PVFI, fluvial) IAMPOL 1150 SOROCA(PVFS, -

Report on Implementation Progress of Projects Managed by the Capmu As of September 30, 2007

CONSOLIDATED AGRICULTURAL PROJECTS’ MANAGEMENT UNIT, FINANCED BY THE WORLD BANK (CAPMU WB) REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS OF PROJECTS MANAGED BY THE CAPMU AS OF SEPTEMBER 30, 2007 Developed by CAPMU management CHISINAU October 2007 1 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ACSA Agency for Consultancy and Training in Agriculture ALRC Agency for Land Relations and Cadastre BCO Branch Cadastral Office CAPMU Consolidated Agricultural Projects Management Unit CIS Commonwealth of Independent States DA Development Agency EIA Environmental Impact Assessment FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GIS Geographical Information System GOM Government of Moldova LFA Logical Framework Approach LPSP Land Privatization Support Project (funded by USAID) MAFI Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry NGO Non Governmental Organization PFI Participating Financial Institution PM Project Manager RISPII Rural Investment and Services Project II SIDA Swedish Development Agency TCO Territorial Cadastral Office TL Team Leader USAID US Agency for International Development WB World Bank 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS RURAL INVESTMENT AND SERVICES PROJECT ........................................................................... 6 PROJECT OBJECTIVES ...............................................................................................................6 PROJECT COMPONENTS.............................................................................................................6 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS ..................................................................................8 -

Moldova Country Fact-Sheet

MOLDOVA COUNTRY FACT-SHEET CONTENTS OVERVIEW • GENERAL INFORMATION ON MOLDOVA • SOCIO-ECONOMIC SITUATION • PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION • SOCIAL WELFARE • PENSIONS • MEDICAL CARE • HOUSING • EMPLOYMENT • REINTEGRATION AND RECONSTRUCTION ASSISTANCE • EDUCATION • VULNERABLE PERSONS • IO’S/NGO’S • ACCESS TO FINANCIAL SERVICES IOM Moldova/ Chisinau International Organization for Migration IOM str. 36/1 Ciuflea, CHIŞINĂU MD 2001, REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Misiunea în Republica Moldova str. Ciuflea 36/1, "Infocentru", , CHIŞINĂU MD 2001, REPUBLICA MOLDOVA Tel. +37322/ 23 29 40; 23 29 41; 23 47 01. Fax. +37322/ 23 28 62. E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Moldova, Regions, Municipalities ........................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................ 4 1. GENERAL INFORMATION ON MOLDOVA. PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION........................................................ 4 1.1 Geography................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 History ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Population and Language ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.4 -

Data As Reported by National Authorities Data As at 14/03/2021, 18:00 P.M

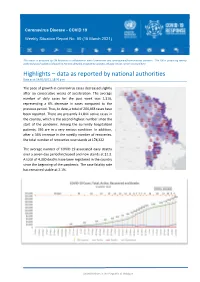

Coronavirus Disease - COVID 19 Weekly Situation Report No. 50 (15 March 2021) This report is produced by UN Moldova in collaboration with Government and development/humanitarian partners. The UN is producing weekly epidemiological updates followed by monthly detailed programme updates. All past sitreps can be accessed here Highlights – data as reported by national authorities Data as at 14/03/2021, 18:00 p.m. The pace of growth in coronavirus cases decreased slightly after six consecutive weeks of acceleration. The average number of daily cases for the past week was 1,316, representing a 6% decrease in cases compared to the previous period. Thus, to date, a total of 204,463 cases have been reported. There are presently 21,811 active cases in the country, which is the second-highest number since the start of the pandemic. Among the currently hospitalized patients, 336 are in a very serious condition. In addition, after a 36% increase in the weekly number of recoveries, the total number of recoveries now stands at 178,322. The average number of COVID-19-associated daily deaths over a seven-day period increased and now stands at 31.3. A total of 4,330 deaths have been registered in the country since the beginning of the pandemic. The case fatality rate has remained stable at 2.1%. United Nations in the Republic of Moldova Republic of Moldova Covid-19 Weekly Situation Report No. 50 | 2 The overall crude cumulative incidence of cases per 100,000 is 5,886. The crude cumulative incidence of cases is 265 and 547 for the last 7 and 14 days, respectively. -

Highlights – Data As Reported by National Authorities Data As at 10/05/2021, 18:00 P.M., Unless Stated Otherwise

Coronavirus Disease - COVID 19 Weekly Situation Report No. 55 (11 May 2021) This report is produced by UN Moldova in collaboration with Government and development/humanitarian partners. The UN is producing weekly epidemiological updates followed by monthly detailed programme updates. All past sitreps can be accessed here Highlights – data as reported by national authorities Data as at 10/05/2021, 18:00 p.m., unless stated otherwise. The total number of COVID‐19 cases in the country has The number of new cases has decreased over continued to increase, albeit at a slower pace than in the last week and reached a 7‐day average of the previous two months, and on May 9, the total 202 on May 9 compared to 314 for the number of cases reached 252,749. An additional 49 preceding week. cases were registered on May 10. The number of active cases has decreased in the past The 7‐day average for the number of deaths has week. As of May 9, the number of active cases stood slightly increased and stands at 16, compared to 15 in at 3,263 which decreased to 3,109 on the first day of the week prior. The total number of deaths as of May the new week. 9 was 5,952 and six additional deaths were registered on May 10. United Nations in the Republic of Moldova Republic of Moldova Covid-19 Weekly Situation Report No. 55 | 2 The average number of very serious cases has Overall, fifty‐nine percent of all cases have been decreased and as of May 9 it stood at 185.