Feminist Solidarities: Theoretical and Practical Complexities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Workers in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay

* UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR FRANCES PERKINS, Secretary WOMEN’S BUREAU MARY ANDERSON, Director + WOMEN WORKERS IN ARGENTINA, CHILE, AND URUGUAY ; J^TCSO^ Bulletin of the Women’s Bureau, No. 195 *rf % M as > UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE t WASHINGTON : 1942 r ) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 5 cents Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis CONTENTS Page. Letter of transmittal m The professions 2 Government service----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Business 2 Personal service---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 w Industry— Agriculture. a Industrial home work--------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Labor legislation-------------------------- 9 Trade unions and organizations------------------------------------------------------------- 10 Classes and schools 11 Women’s organizations------------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 References 15 TABLES Extent of Women’s employment in chief woman-employing industries---------- 3 Employment of women in 26 factories visited 3 ii Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Letter of Transmittal United States Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau, Washington, October 27, 191$. Madam: I have the honor to transmit a report summarizing the findings of the Women’s Bureau staff member appointed as its Inter- American -

The Challenges of Women's Participation In

International IDEA, 2002, Women in Parliament, Stockholm (http://www.idea.int). This is an English translation of Elisa María Carrio, “Los retos de la participacíon de las mujeres en el Parlamento. Una nueva Mirada al caso argentine,” in International IDEA Mujeres en el Parlamento. Más allá de los números, Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. (This translation may vary slightly from the original text. If there are discrepancies in the meaning, the original Spanish version is the definitive text). CASE STUDY The Challenges of Women’s Participation in the Legislature: A New Look at Argentina ELISA MARÍA CARRIO In Argentina, mass-based political parties included a degree of the participation of women going back to their early days, from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, but it was only in the 1980s that we saw the massive emergence of women in party politics. This led to changes in attitude in the search for points of agreement and common objectives. Many women understood that the struggle against women’s oppression should not be subordinated to other struggles, as it was actually compatible with them, and should be waged simultaneously. It was an historic opportunity, as Argentina was emerging from a lengthy dictatorship in which women had the precedent of the mobilizations of the grandmothers and mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, in their white scarves. While women in Argentina have had the right to “vote and be elected” since 1947, women’s systematic exclusion from the real spheres of public power posed one of the most crucial challenges to, and criticisms of, Argentina’s democracy. -

Women in Argentina

Women in Argentina Copyright 2000 by Mónica Szurmuk. This work is licensed under a modified Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You are free to elec- tronically copy, distribute, and transmit this work if you attribute au- thorship. However, all printing rights are reserved by the University Press of Florida (http://www.upf.com). Please contact UPF for information about how to obtain copies of the work for print distribution. You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the University Press of Florida. Nothing in this li- cense impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights. Florida A&M University, Tallahassee Florida Atlantic University, Boca aton Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers Florida International University, Miami Florida State University, Tallahassee University of Central Florida, Orlando University of Florida, Gainesville University of North Florida, Jacksonville University of South Florida, Tampa University of West Florida, Pensacola University Press of Florida Gainesville · Tallahassee · Tampa · Boca aton · Pensacola · Orlando · Miami · Jacksonville · Ft. Myers Women in Argentina Early Travel Narratives · Mónica Szurmuk Copyright 2000 by Mónica Szurmuk Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper All rights reserved 05 04 03 02 01 00 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szurmuk, Mónica. -

Lande Final Draft

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Daring to Love: A History of Lesbian Intimacy in Buenos Aires, 1966–1988 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/350586xd Author Lande, Shoshanna Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Daring to Love: A History of Lesbian Intimacy in Buenos Aires, 1966–1988 DISSERTATION submitted in partiaL satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Shoshanna Lande Dissertation Committee: Professor Heidi Tinsman, Chair Associate Professor RacheL O’Toole Professor Jennifer Terry 2020 © 2020 Shoshanna Lande DEDICATION To my father, who would have reaLLy enjoyed this journey for me. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Abbreviations iv List of Images v AcknowLedgements vi Vita ix Abstract x Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Secret Lives of Lesbians 23 Chapter 2: In the Basement and in the Bedroom 57 Chapter 3: TextuaL Intimacy: Creating the Lesbian Intimate Public 89 Chapter 4: After the Dictatorship: Lesbians Negotiate for their Existence 125 ConcLusion 159 Bibliography 163 iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ALMA Asociación para la Liberación de la Mujer Argentina ATEM Asociación de Trabajo y Estudio sobre la Mujer CHA Comunidad HomosexuaL Argentina CONADEP Comisión NacionaL sobre la Desaparición de Personas ERP Ejército Revolucionario deL Pueblo FAP Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas FAR Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias FIP Frente de Izquierda Popular FLH Frente de Liberación HomosexuaL FLM Frente de Lucha por la Mujer GFG Grupo Federativo Gay MLF Movimiento de Liberación Feminista MOFEP Movimiento Feminista Popular PST Partido SociaLista de Los Trabajadores UFA Unión Feminista Argentina iv LIST OF IMAGES Page Image 3.1 ELena Napolitano 94 Image 4.1 Member of the Comunidad Homosexual Argentina 126 Image 4.2 Front cover of Codo a Codo 150 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Like any endeavor, the success of this project was possible because many people heLped me aLong the way. -

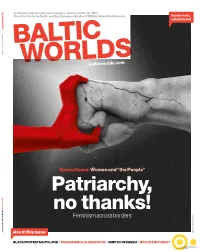

Patriarchy, No Thanks!

BALTIC WORLDSBALTIC A scholarly journal and news magazine. January 2020. Vol. XIII:1. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. Gender hate, a global trend January 2020. Vol. XIII:1 Vol. 2020. January BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com Special Issue: Women and “the People” Patriarchy, Special Issue: Issue: Special Women and “the People” “the and Women no thanks! Feminism across borders also in this issue Sunvisson Karin Illustration: BLACK PROTESTS IN POLAND / #NIUNAMENOS IN ARGENTINA / #METOO IN RUSSIA / MARCH 8 IN TURKEY Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies theme issue WORLDSbalticworlds.com Women and “the People” introduction 3 Conflicts and alliances in a polarized world, Jenny editorial Gunnarsson Payne essays 6 Women as “the People”. Reflections on the Black Protests, Worlds and words beyond Jenny Gunnarsson Payne henever I meet a new reader in particular gender studies. Here, 31 Women, gender, and who is unfamiliar with the we aim to go deeper and under- the authoritarianism of journal Baltic Worlds, I have to stand how the rhetoric and the “traditional values” in explain that the journal covers resistance from women as a group Russia, Yulia Gradskova Wa much bigger area than the title indicates. We is connected in time and space. We 37 Did #MeToo skip Russia? include post-socialist countries in Eastern and want to test how we understand Anna Sedysheva Central Europe, Russia, the former Soviet states the changes in our area for women 67 National and transnational (extending down to the Caucasus), and the and gender, by exploring develop- articulations. -

Reforming Representation: the Diffusion of Candidate Gender Quotas Worldwide Mona Lena Krook Washington University in St

Politics & Gender, 2 (2006), 303–327. Printed in the U.S.A. Reforming Representation: The Diffusion of Candidate Gender Quotas Worldwide Mona Lena Krook Washington University in St. Louis In recent years, more than a hundred countries have adopted quotas for the selection of female candidates to political office. Examining individual cases of quota reform, schol- ars offer four basic causal stories to explain quota adoption: Women mobilize for quotas to increase women’s representation, political elites recognize strategic advantages for supporting quotas, quotas are consistent with existing or emerging notions of equality and representation, and quotas are supported by international norms and spread through transnational sharing. Although most research focuses on the first three accounts, I argue that the fourth offers the greatest potential for understanding the rapid diffusion of gen- der quota policies, as it explicitly addresses the potential connections among quota campaigns. In a theory-building exercise, I combine empirical work on gender quotas with insights from the international norms literature to identify four distinct international and transnational influences on national quota debates: international imposition, trans- national emulation, international tipping, and international blockage. These patterns reveal that domestic debates often have international and transnational dimensions, at the same time that they intersect in distinct ways with international and transnational trends. As work on gender quotas continues to grow, therefore, I call on scholars to move away from simple accounts of diffusion to a recognition of the multiple processes shap- ing the spread of candidate gender quotas worldwide. I would like to thank Judith Squires, Sarah Childs, Ewan Harrison, and participants in the Insti- tute for Social and Economic Research and Policy Graduate Fellows Workshop at Columbia Uni- versity, as well as the editors and three anonymous reviewers at Politics & Gender, for their helpful comments. -

Gender Policies and Armed Forces in Latin America's Southern Cone

Gender Policies and Armed Forces in Latin America’s Southern Cone By Sabina Frederic & Sabrina Calandrón The present article first examines the contribution of international organizations to the formulation and implementation of gender integration policies in the armed forces of the Latin American Southern Cone’s three main countries : Argentina, Brazil and Chile. It focuses on and accounts for the various policy contents and levels of implementation in those nations during the 2000-2014 time-bracket as a result of the dissemination of United Nations (UN) Resolution 1325. The said resolution, adopted in 2000, reaffirmed the crucial role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts, peace negotiations, peace-building, peacekeeping, humanitarian response and post-conflict reconstruction, and stresses the importance of their equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security.1 The study analyzes the responses, influenced by their respective national contexts, of each of the three countries to that UN Resolution. It will additionally highlight the long- standing local initiatives of the three countries on this subject, and also the various points of contact at the transnational level : the latter clearly shows the distinct regional dimension of gender integration policies in the armed forces of Argentina, Chile, and – to a lesser extent – Brazil. It focuses on the factors that have contributed to such regional policy coherence, as well as those differentiating their gender agendas and policies. The particular concerns of each country, its government procedures, and the situation of its national defence institutions in the context of the democratization of the State and its armed forces are examined along the way. -

Introduction Chapter 1. Anarchist Feminism in Nineteenth-Century

Notes 203 Notes Introduction 1. The results were published in Young (et al.) (1984). 2. Research for these various projects was undertaken in South Yemen, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Cuba, Russia, Azerbaijan, Hungary and Iraq. The resulting publications include: The Ethiopian Revolution (Halliday and Molyneux, 1982); State Policies and the Position of Women in the PDRY (Molyneux, 1982); ‘Women’s Emancipation under Socialism: A Model for the Third World?’, World Development (Molyneux, 1980); ‘Legal Reform and Socialist Revolution in Democratic Yemen’, International Journal of the Sociology of Law (Molyneux, 1986a); ‘ “The Woman Question” in the Age of Perestroika’, New Left Review, no 183 (Molyneux, 1990); ‘The Woman Question in the Age of Communism’s Collapse’, in Mary Evans (1994); and ‘Women’s Rights and Political Contingency’ (1995). 3. La Voz de la Mujer (1997). 4. These include De Beauvoir (1953), Mitchell (1965), Rowbotham (1972). Chapter 1. Anarchist Feminism in Nineteenth-Century Argentina 1. The research on La Voz was carried out in the archives of the Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. 2. See Abad de Santillán (1930), Nettlau (1971) and Oved (1978). 3. O Jornal das Senhoras, for example, appeared in Brazil in 1852 and was dedicated to the ‘social betterment and the moral emancipation of women’ (Hahner, 1978). 4. Ferns (1960). 5. Bourdé (1974). 6. On the eve of World War I, 30 per cent of the Argentine population were immigrants in contrast to 14 per cent of the US population in 1910 (Solberg, 1970). 7. Ibid. 8. Anarchist ideas were not all imported. There were indigenous anarchist currents in Argentina and forms of spontaneous popular resistance – but these were unable to achieve a stable organisational expression. -

Gender and Policy in Argentina and Mexico A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Do Women Represent Women? Gender and Policy in Argentina and Mexico A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Jennifer M. Piscopo Committee in charge: Professor Peter H. Smith, Chair Professor Scott W. Desposato Professor Christine Hünefeldt Professor Sebastian Saiegh Professor Carlos Waisman 2011 Jennifer M. Piscopo, 2011 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jennifer M. Piscopo is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii DEDICATION For Dad. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .............................................................................................................. iii Dedication ...................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ v List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................. viii List of Figures ................................................................................................................ xi List of Tables ............................................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... -

Gender and Protests

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Political Science Political Science 2019 REPRESSION AND WOMEN’S DISSENT: GENDER AND PROTESTS Dakota Thomas University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1186-7470 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.191 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Thomas, Dakota, "REPRESSION AND WOMEN’S DISSENT: GENDER AND PROTESTS" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Political Science. 27. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/polysci_etds/27 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Political Science by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

STAGING FEMINISM: THEATRE and WOMEN's RIGHTS in ARGENTINA (1914-1950) May Summer Farnsworth a Dissertation Submitted to the Fa

STAGING FEMINISM: THEATRE AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ARGENTINA (1914-1950) May Summer Farnsworth A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (Spanish American). Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: Advisor: Professor María A. Salgado Reader: Professor Stuart A. Day Reader: Professor Adam Versényi Reader: Professor Laurence Aver y Reader: Professor Rosa Perelmuter ii © 2006 May Summer Farnsworth ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT MAY SUMMER FARNSWORTH: Staging Feminism: Theatre and Women’s Rights in Argentina (1914-1950) (Under the direction of María A. Salgado) In this dissertation I discuss the ways in which socially conscious playwrights in early -twentieth century Argentina used and adapted theatre genres to advance women’s rights and project the feminist imagination. I also anal yze how theatre critics and spectators reacted to these early feminist spectacles. In Chapter 1, I provide an overview of the repression of women that was dictated by the Argentine Civil Code and the efforts of feminist activists to make reforms. I also de scribe how various playwrights (Salvadora Medina Onrubia, José González Castillo, César Iglesias Paz, Alfonsina Storni, and Malena Sándor) used the genre of thesis drama to support social and legislative progress from 1914 to 1937. I explain , in Chapter 2, how marginalized female playwrights (Lola Pita Martínez, Alcira Olivé, Carolina Alió, Salvadora Medina Onrubia and Alfonsina Storni) cultivated the unique strategy of “feminist melodrama,” which allowed them to endorse feminism from within an accepted “fe minine” genre. -

Female Political Leadership in the Southern Cone : Roles and Perceptions of Women in Formal Politics

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2013 Female political leadership in the Southern Cone : roles and perceptions of women in formal politics. Rosslyn Elliott Steinmetz University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Steinmetz, Rosslyn Elliott, "Female political leadership in the Southern Cone : roles and perceptions of women in formal politics." (2013). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 24. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/24 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Female Political Leadership in the Southern Cone: Roles and Perceptions of Women in Formal Politics By Rosslyn Elliott Steinmetz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude and for Graduation with Honors from the Department of Political Science University of Louisville May, 2013 Foreword Two years ago I was not even aware of the existence of gender quotas in Latin America, but in 2011 I went to study in Buenos Aires, Argentina for one year. I took a course on the history of gender in Latin America, and I became fascinated with the subject of women’s participation in politics.