Anomalies in Manipur's Census, 1991–2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stratified Random Sampling - Manipur (Code -21)

Download The Result Stratified Random Sampling - Manipur (Code -21) Species Selected for Stratification = Cattle + Buffalo Number of Villages Having 100 + (Cattle + Buffalo) = 728 Design Level Prevalence = 0.126 Cluster Level Prevalence = 0.03 Sensitivity of the test used = 0.9 Total No of Villages (Clusters) Selected = 85 Total No of Animals to be Sampled = 1785 Back to Calculation Number Cattle of units Buffalo Cattle DISTRICT_NAME BLOCK_CODE BLOCK_NAME VILLAGE_NAME Buffaloes Cattle + all to Proportion Proportion Buffalo sample Bishnupur 2 Bishnupur Potsangbam And Upokpi 19 253 272 303 20 1 19 Bishnupur 15 Kumbi Kumbi (NP) - Ward No.3 32 296 328 328 20 2 18 Bishnupur 2 Bishnupur Nachou 0 704 704 726 21 0 21 Nambol (M Cl) (Part) - Bishnupur 29 Nambol 15 1200 1215 1222 21 0 21 Ward No.15 Chandel 3 Chakpikarong Charoiching 1 105 106 129 19 0 19 Chandel 24 Machi Laiching Minou 5 113 118 118 19 1 18 Chandel 51 Tengnoupal A.Khullen 0 124 124 124 19 0 19 Chandel 4 Chandel Khudei Khunou 14 114 128 145 19 2 17 Chandel 4 Chandel New Chayang 0 173 173 173 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Laiching Khunou 17 165 182 216 20 2 18 Chandel 24 Machi M.Ringpam 0 190 190 190 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Konaitong 0 196 196 196 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Khunbi 0 222 222 222 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Heinoukhong 0 249 249 249 20 0 20 Chandel 3 Chakpikarong Khullenkhallet 111 140 251 314 20 9 11 Chandel 4 Chandel Beru Khudam 0 274 274 274 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Laiching Kangshang 0 308 308 414 20 0 20 Churachandpur 46 Singngat Tuikuimuallum 4 116 120 120 19 1 18 Churachandpur -

District Census Handbook Senapati

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI 1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI MANIPUR SENAPATI DISTRICT 5 0 5 10 D Kilometres er Riv ri a N b o A n r e K T v L i G R u z A d LAII A From e S ! r Dimapur ve ! R i To Chingai ako PUNANAMEI Dzu r 6 e KAYINU v RABUNAMEI 6 TUNGJOY i C R KALINAMEI ! k ! LIYAI KHULLEN o L MAO-MARAM SUB-DIVISION PAOMATA !6 i n TADUBI i rak River 6 R SHAJOUBA a Ba ! R L PUNANAMEIPAOMATA SUB-DIVISION N ! TA DU BI I MARAM CENTRE ! iver R PHUBA KHUMAN 6 ak ar 6 B T r MARAM BAZAR e PURUL ATONGBA v r i R ! e R v i i PURUL k R R a PURUL AKUTPA k d C o o L R ! g n o h k KATOMEI PURUL SUB-DIVISION A I CENTRE T 6 From Tamenglong G 6 TAPHOU NAGA P SENAPATI R 6 6 !MAKHRELUI TAPHOU KUKI 6 To UkhrulS TAPHOU PHYAMEI r e v i T INDIAR r l i e r I v i R r SH I e k v i o S R L g SADAR HILLS WEST i o n NH 2 a h r t I SUB-DIVISION I KANGPOKPI (C T) ! I D BOUNDARY, STATE......................................................... G R SADAR HILLS EAST KANGPOKPI SUB-DIVISION ,, DISTRICT................................................... r r e e D ,, v v i i SUB-DIVISION.......................................... R R l a k h o HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT......................................... p L SH SAIKUL i P m I a h c I R ,, SUB-DIVISION................................ -

Area and Population

1. AREA AND POPULATION This section includes abstract of available data on area and population of the Indian Union based on the decadal Census of population. Table 1.1 This table contains data on area, total population and its classification according to sex and urban and rural population. In the Census, urban area is defined as follows: (a) All statutory towns i.e. all places with a municipality, corporation, cantonment board or notified town area committee etc. (b) All other places which satisfy the following criteria: (i) a minimum population of 5,000. (ii) at least 75 per cent of male working population engaged in non-agricultural pursuits; and (iii) a density of population of at least 400 persons per sq.km. (1000 per sq. mile) Besides, Census of India has included in consultation with State Governments/ Union Territory Adminis- trations, some places having distinct urban charactristics as urban even if such places did not strictly satisfy all the criteria mentioned under category (b) above. Such marginal cases include major project colonies, areas of intensive industrial development, railway colonies, important tourist centres etc. In the case of Jammu and Kashmir, the population figures exclude information on area under unlawful occupation of Pakistan and China where Census could not be undertaken. Table 1.2 The table shows State-wise area and population by district-wise of Census, 2001. Table 1.3 This table gives state-wise decennial population enumerated in elevan Censuses from 1901 to 2001. Table 1.4 This table gives state-wise population decennial percentage variations enumerated in ten Censuses from 1901 to 1991. -

Baseline Survey of Minority Concentration Districts

BaselineBaseline Survey Survey of of Minority Minority Concentration Concentration Districts: An Overview of the Findings Districts: An Overview of the Findings D. Narasimha Reddy* I Introduction It is universally recognized that promotion and protection of the rights of persons belonging to minorities contribute to the political and social stability of the countries in which they live. India, a country with a long history and heritage, is known for its diversity in matters of religion, language and culture. ‘Unity in diversity’ is an oft-repeated characterization of India as well as a much-cherished aspiration, reflected in the constitutional commitment relating to the equality of citizens and the responsibility of the State to D.preserve, Narasimha protect and assure Reddy the rights of the minorities. Over the years, the process of development in the country did raise questions about the fair share of minorities, and point towards certain groups of them being left behind. “Despite the safeguard provided in the Constitution and the law in force, there persists among the minorities a feeling of inequality and discrimination. In order to preserve secular traditions and to promote National Integration, the Government of India attaches the highest importance to the enforcement of the safeguards provided for the minorities and is of firm view that effective institutional arrangements are urgently required for the enforcement and implementation of all the safeguards provided for the minorities in the Constitution, in the Central and State Laws and in the government policies and administrative schemes enunciated from time to time.” (MHA Resolution Notification No. II-16012/2/77 dated 12.01.1978). -

Some Success Stories

Some Success Stories: Animal Husbandry: Poultry Farming: A project on giriraja poultry farming was implemented at Central Agricultural University, Imphal, Manipur for socio- economic upliftment of scheduled caste community in Imphal-East District, Manipur. Training and demonstration on scientific Giriraja rearing, marketing, formation of SHG was conducted and Giriraja one week old chicks along with feeds and medicines were distributed to the farmers. More than 200 rural farmers/ youth were benefitted from 10 villages of Imphal-East District of Manipur. With the sponsorship of project poor and marginal farmers of rural societies of Andro especially, the women cluster of Andro project most of the dropped out students who discontinued their studies after matriculation have started going to colleges. Besides most the families covered under this project have given up local liquor (Kalei) production. Prof. M. S. Swaminathan visited the poultry farm at Central Agricultural University Sustainable livelihood generation of rural women through improved backyard poultry farming was implemented at College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, Central Agricultural University, Mizoram. 541 parent Vanaraja chicks were purchased from Project Directorate of Poultry, Hyderabad. The birds were reared in deep litter system of management in the Instructional Poultry Farm Complex of the College. 10 women from ten selected villages were imparted training on scientific rearing of vanaraja poultry to enhance their skill to serve as local service providers in their respective villages and rural poultry resource centre were established. Management& Distribution of Chicks, Medicines and Feeds to the Beneficiaries Emu and Turkey Rearing: Emu and Turkey farming for economic upliftment of scheduled tribe families in Senapati district, Manipur was implemented in KVK, Sylvan, Manipur. -

District Census Handbook, Chandel, Part-XII a & B, Series-15, Manipur

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES-I5 MANIPUR DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Part XII - A & B CHANDEL VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY & VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT Y. Thamkishore Singh,IAS Director of Census Operations, Manipur Product Code Number ??-???-2001 - Cen-Book (E) DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK: CHAN DEL Motif of Chandel District Mithun Mithun is a rare but prized animal among the ethnic tribes of Chandel District, bordering with Myanmar, not only nowadays but also in olden days. Only well-to-do families could rear the prized animal and therefore occupy high esteem in the society. It is even now, still regarded as prestigious animal. In many cases a bride's price and certain issues are settled in terms of Mithun (s). Celebration and observation of important occasion like festivals, anniversaries etc. having customary, social and religious significance are considered great and successful if accompanied with feasting by killing Mithun (s). (iii) DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK: CHANDEL (iv) DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK: CHAN DEL Contents Pages Foreword IX-X Preface Xl-XU Acknowledgements xiii District highlights - 200 I Census xiv Important Statistics in the District-2001 XV-XVI Statements 1-9 xvii-xxii Statement-I: Name of the headquarters of districtlsub-division,their rural-urban status and distance from district headquarters, 200 I Statement-2: Name of the headquarters of districtlTD/CD block their rural urban status and distance from district headquarters, 200 I Statement-3: Population of the district at each census from 1901 to 2001 Statement-4: Area, number of villalges/towns and population in district and sub- division, 2001 Statement-5: T.DIC.D. -

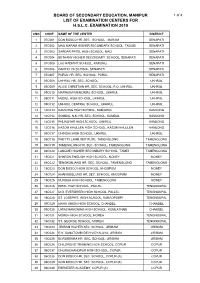

Board of Secondary Education, Manipur List of Examination Centers

BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION, MANIPUR 1 of 4 LIST OF EXAMINATION CENTERS FOR H.S.L.C. EXAMINATION 2019 CNO CODE NAME OF THE CENTER DISTRICT 1 07C001 DON BOSCO HR. SEC. SCHOOL , MARAM SENAPATI 2 07C002 MAO MARAM HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, TADUBI SENAPATI 3 07C003 SARDAR PATEL HIGH SCHOOL, MAO SENAPATI 4 07C004 BETHANY HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, SENAPATI SENAPATI 5 07C005 LAO RADIANT SCHOOL, KARONG SENAPATI 6 07C006 DAIKHO VA SCHOOL, SENAPATI SENAPATI 7 07C007 PURUL HR. SEC. SCHOOL, PURUL SENAPATI 8 05C008 UKHRUL HR. SEC. SCHOOL UKHRUL 9 05C009 ALICE CHRISTIAN HR. SEC. SCHOOL, P.O. UKHRUL UKHRUL 10 05C010 MARINGMI MEMORIAL SCHOOL, UKHRUL UKHRUL 11 05C011 MODEL HIGH SCHOOL, UKHRUL UKHRUL 12 05C012 UKHRUL CENTRAL SCHOOL, UKHRUL UKHRUL 13 12C013 KAMJONG HIGH SCHOOL, KAMJONG KAMJONG 14 12C014 SOMDAL N.K. HR. SEC. SCHOOL, SOMDAL KAMJONG 15 12C015 PHUNGYAR HIGH SCHOOL, UKHRUL KAMJONG 16 12C016 KASOM KHULLEN HIGH SCHOOL, KASOM KHULLEN KAMJONG 17 05C017 CHINGAI HIGH SCHOOL, UKHRUL UKHRUL 18 08C018 PRETTY LAMB INSTITUTE, TAMENGLONG TAMENGLONG 19 08C019 TAMENGLONG HR. SEC. SCHOOL, TAMENGLONG TAMENGLONG 20 08C020 LANGMEI HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, TAMEI TAMENGLONG 21 15C021 SHARON ENGLISH HIGH SCHOOL, NONEY NONEY 22 08C022 TENGKONJANG HR. SEC. SCHOOL, TAMENGLONG TAMENGLONG 23 15C023 DON BOSCO HIGH SCHOOL, KHOUPUM NONEY 24 15C024 KHANGSILLUNG HR. SEC. SCHOOL, KHOUPUM NONEY 25 15C025 NUNGBA HIGH SCHOOL, TAMENGLONG NONEY 26 16C026 IDEAL HIGH SCHOOL, PALLEL TENGNOUPAL 27 16C027 M.G. EVERGREEN HIGH SCHOOL, PALLEL TENGNOUPAL 28 16C028 ST. JOSEPH'S HIGH SCHOOL, KURAOPOKPI TENGNOUPAL 29 09C029 MAHA UNION HIGH SCHOOL, CHANDEL CHANDEL 30 09C030 LIWACHANGNING HIGH SCHOOL, KOMLATHABI CHANDEL 31 16C031 MOREH HIGH SCHOOL, MOREH TENGNOUPAL 32 16C032 ST. -

Chapter V Socio-Cultural Organization and Change

107 Chapter V Socio-Cultural Organization and Change 5.1 Introduction From very early times the Poumai Naga have been practicing a direct democratic form of government in the village, combining it with their own culture and tradition, to retain their identity as the people of Poumai. The Poumai Naga tribe is in a transitional stage: though they practice agriculture as the main occupation, they have not left hunting and gathering fruits which still continues side by side There was no written history of Poumai Nagas but it is conspicuous that there were changes in their economic and socio-cultural life. In retrospect, to understand the changes within the Poumai Naga community, from pre-British period to the present day, the history of socio-cultural changes have conveniently been divided into different periods. 5.2 Pre-British arrival to tlie Naga Hills (- 1832) Before the arrival of the British to the Naga Hills, the Poumai Nagas were not exposed to the outside world. Headhunting at this time was at its zenith, with lots of pride but hatred, fear and jealousy filled their hearts. Fishing, hunting and shifting cultivation were the main occupations in the pre- British period. The Poumai Naga had no caste system in terms of high or low, pure and untouchables, rich or poor. It functioned, as an independent democratic society within a community set-up where helping ones clansmen in every respect was the hallmark of their lives. 5.2.1 Family The Poumai Naga community believes in a patriarchal family system. In many of the Naga villages, large families ranging from to 8-10 members in a family are common. -

List of School

Sl. District Name Name of Study Centre Block Code Block Name No. 1 1 SENAPATI Gelnel Higher Secondary School 140101 KANGPOKPI 2 2 SENAPATI Damdei Christian College 140101 KANGPOKPI 3 3 SENAPATI Presidency College 140101 KANGPOKPI 4 4 SENAPATI Elite Hr. Sec. School 140101 KANGPOKPI 5 5 SENAPATI K.T. College 140101 KANGPOKPI 6 6 SENAPATI Immanuel Hr. Sec. School 140101 KANGPOKPI 7 7 SENAPATI Ngaimel Children School 140101 KANGPOKPI 8 8 SENAPATI T.L. Shalom Academy 140101 KANGPOKPI 9 9 SENAPATI John Calvin Academy 140102 SAITU 10 10 SENAPATI Ideal English Sr. Sec. School 140102 SAITU 11 11 SENAPATI APEX ENG H/S 140102 SAITU 12 12 SENAPATI S.L. Memorial Hr. Sec. School 140102 SAITU 13 13 SENAPATI L.M. English School 140102 SAITU 14 14 SENAPATI Thangtong Higher Secondary School 140103 SAIKUL 15 15 SENAPATI Christian English High School 140103 SAIKUL 16 16 SENAPATI Good Samaritan Public School 140103 SAIKUL 17 17 SENAPATI District Institute of Education & Training 140105 TADUBI 18 18 SENAPATI Mt. Everest College 140105 TADUBI 19 19 SENAPATI Don Bosco College 140105 TADUBI 20 20 SENAPATI Bethany Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 21 21 SENAPATI Mount Everest Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 22 22 SENAPATI Lao Radiant School 140105 TADUBI 23 23 SENAPATI Mount Zion Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 24 24 SENAPATI Don Bosco Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 25 25 SENAPATI Brook Dale Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 26 26 SENAPATI DV School 140105 TADUBI 27 27 SENAPATI St. Anthony’s School 140105 TADUBI 28 28 SENAPATI Samaritan Public School 140105 TADUBI 29 29 SENAPATI Mount Pigah Collage 140105 TADUBI 30 30 SENAPATI Holy Kingdom School 140105 TADUBI 31 31 SENAPATI Don Bosco Hr. -

SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program – Tranche 1

Social Safeguard Due Diligence Report July 2017 IND: SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program – Tranche 1 Prepared by Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of May 2017) Currency unit – Indian Rupee (Rs) INR1.00 = $ 0.01555 $1.00 = INR 64.32 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BSR – Basic Schedule of Rates DC – District Collector DH – Displaced household DP – Displaced person EA – Executing Agency GRC – Grievance Redressal Committee IA – Implementing Agency IAY – Indira Awaas Yojana LA – Land acquisition LAA – Land Acquisition Act, 1894 L&LRO – Land and Land Revenue Office RFCT in LARR – The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Act - 2013 Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 LVC – Land Valuation Committee MORTH – Ministry of Road Transport and Highways NGO – Nongovernment organization NHA – National Highways Act, 1956 NRRP – National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, 2007 PD – Project Director PIU – Project implementation unit MPWD – Manipur Public Works Department WBPWD – West Bengal Public Works (Roads) Department R&R – Resettlement and rehabilitation RF – Resettlement framework RO – Resettlement Officer ROW – Right-of-way RP – Resettlement plan SC – Scheduled caste SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement ST – Scheduled tribe NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This social due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

District Report SENAPATI

Baseline Survey of Minority Concentrated Districts District Report SENAPATI Study Commissioned by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India Study Conducted by Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development: Guwahati VIP Road, Upper Hengerabari, Guwahati 781036 1 ommissioned by the Ministry of Minority CAffairs, this Baseline Survey was planned for 90 minority concentrated districts (MCDs) identified by the Government of India across the country, and the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi coordinates the entire survey. Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati has been assigned to carry out the Survey for four states of the Northeast, namely Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Manipur. This report contains the results of the survey for Senapati district of Manipur. The help and support received at various stages from the villagers, government officials and all other individuals are most gratefully acknowledged. ■ Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development is an autonomous research institute of the ICSSR, New delhi and Government of Assam. 2 CONTENTS BACKGROUND....................................................................................................................................8 METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................................9 TOOLS USED ......................................................................................................................................10 -

(Kabui Village), Part VI, Vol-XXII, Manipur

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XXII MANIPUR, PART VI VfLLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPH 2. KEISAMTHONG (KA~UI VILLAGE) R. K. BrRENDRA SINGH of the M anipur Civil Service Superintendent of Census Operations, Manipur 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, MANIPUR (All the Consus Publications of this Territory will bear Volume No. XXII) PAR'l' loA-General Report (Excluding Subsidiary Tables) PUT I-B-General Report (Subsidiary Tables) General Population Tables PAl.T 1I- Economic Tables (with Sub·parts) { Cultural and MigratiQu Tables PUT III-Household Economic Tables PUT IV-Housing Report and Tables } PART V-Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes In one volume. PAkT VI-Village Survey Monographs PaT VII-A-Haodicrafts Survey R.eports PUT VII·B~Fairs and F()stivals P.Ai.T Vm-A-Administration Report on Enumeration 1 Not for PART VIII-B-Administration Report on Tabulation J sale PU.T IX-Census Atlas Volume (Thill will be a combined volume for Manipur, Tripura and Nagaland) STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATION 1. District Census Handbook Field Investigation: S. Achouba Singh Map and Sketches: O. Keso Singh Photographs : I. Manilal Singh Editing R. K. Birendra Singh II' REVISED LIST OF VILLAGES SELECTED FOR SOCIO·ECONOMIC SlJRVEY Name of Village Name of Sub-Division 1. Ithing** • Bishenpur 2. Keisamthong* (Kabui village) lmphal West 3. Khouliabung Churachandllur 4. Konpui Churachandpl'lf 5. LiwachanglJing Tenglloupal 6. Longa Koireng . Mao and Sadar Hills 7. Minuthong (Kabui village) Imphal West 8. Ningel Thoubal 9. Ginam Sawombung Imphal West 10. Pherzawl** Churachandpur 11. Phunan Sambum TengoQupal 12. Sekmai Imphal West 13. Thanging Chiru** Mao and Sadar Hills 14.