Columbus and the Railroads of Central Ohio Before The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information for Army Meetings ... December 1864

E 635 INFORM^TIOjST J^ i.U569 'Copy 1 FOB .*^^ A liMY MEETINGS. places In many the fourth Sabbath eveDJng of the month is devoted to a TTnion Monthly Concert of Prayer for the Army and Na.y. The deepest inter- est has be^n e:.c,t.d by these meetings. It is hutnbly suggested to all who beheve in the power of prayer, to form «uch meetings during the cri.sis of our mt,on s destiny. This tract is compiled with the view of affording informs lion for these Army Meetings- Please circulate it. DECEMBER, 1864, ansaai^'''^''''^] OFFICERS. GEORGE H. STUART, Esq., Chairman. JOSEPH PATTERS0:N^ Esq., Treasurer, Rev. W. E. BOARDMAN, Sccretart/. Rev. LEMUEL MOSS, Secretary/ Ifgme Organization. Rev. BERNICE D. AMES, Secretary Field Organization. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE. GEO. H STUART, Esq., Philadelphia STEPHEN COLWELL, Esq., Rev. Bishop E. Phllada, S. JANES, D D., N Y WILLIAM E. C. DODGE, Esq., New York, DEMOND, Esq , Boston. Mass. Rev. HEM AN DYER, D. D., New York '^72i!;^^^^^'^' *^«q- Philadelphia. W.S. GRIFFITHS. Esq JAY , Brooklyn, N.Y, COOKE. Esq , Philadelphia. JOSEPH G, S.GIIIEFITHS, Esq., Baltimore, Md. PATTKKSON. Esq., Philad'a. H G. JO.N'E^, Rev. Bishop Esq., Philadelphia. M. SIMPSO.N. D.J)., Phila. Rev. W. E. BOARDM AN, Ex. Off., Phila, PEINIED BT AiFRliD MARTIE.N, 619 A.NJ> 6;il JAYNB 61,, PHILADELPHIA. DIRECTORY. PirtTiAnKLrillA.—Letters to T^ev. W. E. BoarrliiiHii. ICev. Umiiel Mow. or .l.)Sf)ih . Kev Btiiii'e D. Anu-s. 11 H;uik Street; nioiiey to I'atterson. at the Westviii r.iiiik; stores to Cior^'e II. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1280 HON

E1280 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks June 2, 2009 Kacie Walker, Amber Castleman, Amber Bai- HONORING THE HISTORY OF THE position of Midwest apprentice coordinator for ley, Anne Russell, Samantha Hoadwonic, MAD RIVER AND LAKE ERIE the union for 35 years. He traveled the region Megan Chesney, Hannah Porter, Alice RAILROAD to oversee the training of young people in his O’Brien, Maria Frebis, Morgan Lester, profession. Courtney Clark, Breana Thomas, Donte´ HON. JIM JORDAN It was Tom’s connection to and involvement Souviney, Brittany Pendergrast, Ashia Terry, OF OHIO in his community that his friends will remem- Jessica Ayers, Mary Beth Canterberry, Megan IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ber. He was an active member of St. Eu- Kelley, Taylor Lee, Casey Clark, Kelsey gene’s Parish. Not only had he served as an Tuesday, June 2, 2009 Choate, Dene´ Souviney, Leslie Cope, Tara usher for 55 years, he also served as a youth Greer, Amy Russell, Megan Quinn, Rachel Mr. JORDAN of Ohio. Madam Speaker, I basketball coach and a member of the Big Albritton, and Katie Brown. am honored to commend to the House the Brother program. He had a smile and kind work of the Champaign County Bicentennial word for everyone f Historical Marker Committee and the West Tom’s top priority was always his family and Central Ohio Port Authority to promote the his- the love and support they provided him was IN HONOR OF JAY LENO tory of the Mad River and Lake Erie Railroad. most important in his life. In 1948 he married The Mad River and Lake Erie Railroad was his high school sweetheart, Irene Feehan, and chartered by the State of Ohio in 1832, mak- together the couple raised eight children. -

The Albany Rural Cemetery

<^ » " " .-^ v^'*^ •V,^'% rf>. .<^ 0- ^'' '^.. , "^^^v ^^^os. l.\''' -^^ ^ ./ > ••% '^.-v- .«-<.. ^""^^^ A o. V V V % s^ •;• A. O /"t. ^°V: 9." O •^^ ' » » o ,o'5 <f \/ ^-i^o ^^'\ .' A. Wo ^ : -^^\ °'yi^^ /^\ ^%|^/ ^'%> ^^^^^^ ^0 v^ 4 o .^'' <^. .<<, .>^. A. c /°- • \ » ' ^> V -•'. -^^ ^^ 'V • \ ^^ * vP Si •T'V %^ "<? ,-% .^^ ^0^ ^^n< ' < o ^X. ' vv-ir- •.-.-., ' •0/ ^- .0-' „f / ^^. V ^ A^ »r^. .. -H rr. .^-^ -^ :'0m^', .^ /<g$S])Y^ -^ J-' /. ^V .;••--.-._.-- %^c^ -"-,'1. OV -^^ < o vP b t'' ^., .^ A^ ^ «.^- A ^^. «V^ ,*^ .J." "-^U-o^ =^ -I o >l-' .0^ o. v^' ./ ^^V^^^.'^ -is'- v-^^. •^' <' <', •^ "°o S .^"^ M 'V;/^ • =.«' '•.^- St, ^0 "V, <J,^ °t. A° M -^j' * c" yO V, ' ', '^-^ o^ - iO -7-, .V -^^0^ o > .0- '#-^ / ^^ ' Why seek ye the living among the dead }"—Luke xxiv : s. [By i)ormission of Erastus Dow Palmer.] e»w <:3~- -^^ THE ALBANY RURAL ^ CEMETERY ITS F A3Ts^ 5tw copies printeil from type Copyn.y:ht. 1S92 Bv HKNkv 1*. PiiKi.rs l*lioto>;raphy by l*iiic MarPoiiaUl, Albany Typogrnpliy and Prcsswork by Brnndow l^rintinj; Comimny, Albany ac:knowledgments. rlfIS hook is tlir D/i/i^mio/fi of a proposilioii on lite pari ot the Iriixtccx to piihlisli a brief liislorv of the .llhaiiy Cemetery A ssoeiation, iiieliidiiiQa report of the eonseeration oration, poem and other exercises. It li'as snoocsted that it niioht be well to attempt son/e- thino- more worthy of the object than a mere pamphlet, and this has been done with a result that must spealc for itself. Jl'h/le it would be impi-aclicable to mention here all who have kindly aided in the zvork, the author desi/'cs to express his particular oblioations : To Mr. -

Pa-Railroad-Shops-Works.Pdf

[)-/ a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania f;/~: ltmen~on IndvJ·h·;4 I lferifa5e fJr4Je~i Pl.EASE RETURNTO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERVICE CE~TER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CROFIL -·::1 a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania by John C. Paige may 1989 AMERICA'S INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE PROJECT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CONTENTS Acknowledgements v Chapter 1 : History of the Altoona Railroad Shops 1. The Allegheny Mountains Prior to the Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 1 2. The Creation and Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 3 3. The Selection of the Townsite of Altoona 4 4. The First Pennsylvania Railroad Shops 5 5. The Development of the Altoona Railroad Shops Prior to the Civil War 7 6. The Impact of the Civil War on the Altoona Railroad Shops 9 7. The Altoona Railroad Shops After the Civil War 12 8. The Construction of the Juniata Shops 18 9. The Early 1900s and the Railroad Shops Expansion 22 1O. The Railroad Shops During and After World War I 24 11. The Impact of the Great Depression on the Railroad Shops 28 12. The Railroad Shops During World War II 33 13. Changes After World War II 35 14. The Elimination of the Older Railroad Shop Buildings in the 1960s and After 37 Chapter 2: The Products of the Altoona Railroad Shops 41 1. Railroad Cars and Iron Products from 1850 Until 1952 41 2. Locomotives from the 1860s Until the 1980s 52 3. Specialty Items 65 4. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service WAV 141990' National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Cobscook Area Coastal Prehistoric Sites_________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts ' • The Ceramic Period; . -: .'.'. •'• •'- ;'.-/>.?'y^-^:^::^ .='________________________ Suscruehanna Tradition _________________________ C. Geographical Data See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in j£6 CFR Part 8Q^rjd th$-§ecretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. ^"-*^^^ ~^~ I Signature"W"e5rtifying official Maine Historic Preservation O ssion State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this -

WU Editorials & Model Stop

volume one, number two a supplement to walthers ho, n&z and big trains reference books CLASSICS Model Power Acquires Mantua Model Power is pleased to announce its acquisition of Mantua Industries. A respected manufacturer of locomotives and rolling stock for model railroaders since 1926, Mantua is headquartered in Woodbury, New Jersey. Together these manufacturers have a total of over 110 years of experience and service to the model railroad industry. Model Power has purchased all HO tooling, molds, parts and dies from Mantua Industries and retains rights to the name “Mantua.” Model Power will also be forming a new division called Mantua Classics whose initial production plans for 2003 include the following locomotives: Pacific, Berkshire, 2-6-6-2, 2-6-6-0, Camelback and 0-6-0 Tank. The overall goal will be to produce quality products, fine-tune performance, enhance detail and dramatically cut the prices of steam locomotives. For modelers concerned about what this acquisition means in terms of products and customer service, here are steps now being taken by Model Power: 1. Most parts are or will be in stock 2. Metal boiler locomotives will be made with extra details not previously included 3. Steam locomotives will be DCC compatible with an 8-prong receiver 4. Tenders will be made with electrical pickup 5. Drive trains for F7s will be flywheel driven and carry the high-tech F7 metal body used in Model Power’s MetalTrain™ Model Power is proud to offer its customers more—more details, more quality and performance, more choices— with Mantua Classics. -

DEATH of TRU Have Him Around the House Again

A Genuine Pioneer Celebrates Birthday lif In hi him ti up to the ictive n- his on Febru- liisJ I COODBGE TAKEN BY DEATH JjOTfti-'fc—it T©L s STORIES DIES AT * PORT HOME. SHE WAS BORN _KlV&t) 18Q$45 __*•___-. i^uiff t/3* *JU Wrote "Katy Did" Keriea and Oth er 'Well-Known Children'. Book. —Father Wa. a Promi nent Educator. Henry Byal band- of the thelr borne, on East Sam [Specl.l Dispatch from the New York Sun.] NEWPORT, R. I.. April 9.—Miss (1 Willi li Sarah Chauncey Woolsey, better nd trailing known as Susan Coolidge, a writer of •in a (Tali children's stories, died suddenly of ' ill fur IV. heart disease at her home here to-day. Mr. and Mrs. i She was sixty years of age and | Itltlftll flo' 'ill- a daughter of the late John F. V tend their sey, of New Haven. Iforn • h Chaum wa« horn bly realising that the illness * gan reading law with the Hon. 1 in Cls i lS4b. Her family <n with the law LaBlond, and was admitted to the bar in of th' "ok, one of her uncles, flrm, which had been iniiintiiineil during 1869. Before this, he served two years Dwight Woolsey, win • and went to his oil as an enrolling clerk in the house of the Ohio general assembly. ,n educator at the head borne at Wauseon, in the hope that the Mr. Touvelle began the practice of of Yalo University. A cousin of "Su- change woud benefit Lira. Mrs. -

The Steam Locomotive Table, V1

The Steam Locomotive Table, v1 If you’re reading this; you either like steam trains, or want to know more about them. Hopefully, either way, I can scratch your itch with this; a set of randomizer/dice-roll tables of my own making; as inspired by some similar tables for tanks and aircrafts. Bear with me, I know not everyone knows the things I do, and I sure know I don’t know a lot of things other train enthusiasts do; but hopefully the descriptions and examples will be enough to get anyone through this smoothly. To begin, you’ll either want a bunch of dice or any online dice-rolling/number generating site (or just pick at your own whim); and somewhere or something to keep track of the details. These tables will give details of a presumed (roughly) standard steam locomotive. No sentinels or other engines with vertical boilers; no climax, shay, etc specially driven locomotives; are considered for this listing as they can change many of the fundamental details of an engine. Go in expecting to make the likes of mainline, branchline, dockyard, etc engines; not the likes of experiments like Bulleid’s Leader or specific industry engines like the aforementioned logging shays. Some dice rolls will have uneven distribution, such as “1-4, and 5-6”. Typically this means that the less likely detail is also one that is/was significantly less common in real life, or significantly more complex to depict. For clarity sake examples will be linked, but you’re always encouraged to look up more as you would like or feel necessary. -

IL Combo Ndx V2

file IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE The Quarterly Journal of THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE SOCIETY COMBINED INDEX of Volumes 1 to 7 1976 – 1996 IL No.1 to No.79 PROVISIONAL EDITION www.industrial-loco.org.uk IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 INTRODUCTION and ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This “Combo Index” has been assembled by combining the contents of the separate indexes originally created, for each individual volume, over a period of almost 30 years by a number of different people each using different approaches and methods. The first three volume indexes were produced on typewriters, though subsequent issues were produced by computers, and happily digital files had been preserved for these apart from one section of one index. It has therefore been necessary to create digital versions of 3 original indexes using “Optical Character Recognition” (OCR), which has not proved easy due to the relatively poor print, and extremely small text (font) size, of some of the indexes in particular. Thus the OCR results have required extensive proof-reading. Very fortunately, a team of volunteers to assist in the project was recruited from the membership of the Society, and grateful thanks are undoubtedly due to the major players in this exercise – Paul Burkhalter, John Hill, John Hutchings, Frank Jux, John Maddox and Robin Simmonds – with a special thankyou to Russell Wear, current Editor of "IL" and Chairman of the Society, who has both helped and given encouragement to the project in a myraid of different ways. None of this would have been possible but for the efforts of those who compiled the original individual indexes – Frank Jux, Ian Lloyd, (the late) James Lowe, John Scotford, and John Wood – and to the volume index print preparers such as Roger Hateley, who set a new level of presentation which is standing the test of time. -

The Glass Firms at Greenfield, Indiana

The Glass Firms at Greenfield, Indiana Bill Lockhart, Beau Schriever, Bill Lindsey, and Carol Serr When Louis Hollweg – a jobber in crockery, tableware, lamps, and fruit jars – decided to branch out into the glass container manufacturing business in 1890, he built a glass factory that became the scene for five different operators over a 30-year period. Throughout most of its existence, the plant concentrated on fruit jar production, making a variety of jars that can be directly traced to the factory, especially to the Greenfield Fruit Jar & Bottle Co. Once the big- name firms (Ball Brothers and Owens) took over, the plant’s days were numbered. Histories Hollweg & Reese, Indianapolis, Indiana (1868-ca. 1914) Louis Hollweg and Charles E. Reese formed the firm of Hollweg & Reese in 1868. Located at 130-136 South Meridian Street, Indianapolis, Indiana, the company was a direct importer and jobber in crockery, pressed and blown tableware, lamps, lamp paraphernalia, and other fancy goods (Figure 1). After the death of Resse in 1888, Hollweg continued to use the Hollweg & Reese name. The last entry we could find for the firm was in 1913, so Hollweg probably disbanded the firm Figure 1 – Hollweg & Reese (Hyman 1902:354) (or sold out) ca. 1914 – a few years after he exited the glass business (Hyman 1902:354-355; Indiana State School for the Deaf 1914:90). Containers and Marks Although the firm’s main product list did not include containers, Hollweg & Reese apparently began carrying its own line of fruit jars by the 1870s, when William McCully & Co. made the Dictator, a jar similar to a grooved-ring, wax-sealer that was embossed with the 469 Hollweg & Reese name. -

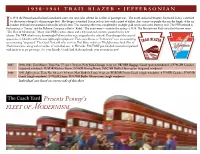

Trailblazer-Jeff.Pdf

1938-1941 TRAIL BLAZER • JEFFERSONIAN n 1938 the Pennsylvania Railroad introduced a new two tone color scheme for it’s fleet of passenger cars. The noted industrial designer, Raymond Loewy is credited for the exterior design for the passenger fleet. His design of standard Tuscan red car sides with a panel of darker, almost maroon-purple that ran the length of the car window level and terminated in half circles at both ends. This stunning effect was completed by multiple gold stripes and a new lettering style. The PRR referred to Ithe lettering as “Futura” and the Pullman Company called it “Kabel.” The trains were to ready in the spring of 1938. The Pennsylvania Railroad called the new trains “The Fleet of Modernism.” Many older PRR coaches, diners and a few head end cars were painted in the new scheme. The PRR rebuilt some heavyweight Pullmans that were assigned to the railroad. They changed the external appearance to blend in with the new lightweight equipment. There were knowe as “betterment” cars, an accounting term meaning “improved.” The Coach Yard will offer an 8-car Trail Blazer and 8-car The Jeffersonian, both Fleet of Modernism trains, along with a number of individual cars, in HO scale, FACTORY pro-finished: lettered and painted Jeffersonian with interiors as per prototype. See your friendly Coach Yard dealer and make your reservations now! 1865 1938-1941 Trail Blazer, Train No. 77 east / 78 west, New York-Chicago 8 car set: PB70ER Baggage Coach (paired windows), 4 P70GSR Coaches (w/paired windows), D70DR Kitchen Dorm, D70CR Dining Room, POC70R Buffet Observation (w/paired windows) 1866 1941 Jeffersonian, Train No. -

Cincinnati 7

- city of CINCINNATI 7 RAILROAD IMPROVEMENT AND SAFETY PLAN Ekpatm~d Tra tim & Engineering Tran~~murnPlanning & Urhn 'Design EXHIBIT Table of Contents I. Executive Summary 1 Introduction 1 Background 7 Purpose 7 I. Enhance Rail Passenger Service to the Cincinnati Union Terminal 15 11. Enhance Freight Railroad Service to and Through Cincinnati 21 111. Identify Railroad Related Safety Improvements 22 RlSP Projects 26 Conclusions 26 Recommendations 27 Credits List of Figures Figure 1 Cincinnati Area Railroads Map (1965) Figure 2 Cincinnati Area Railroads Map (Existing) Figure 3 Amtrak's Cardinal on the C&O of Indiana Figure 4 Penn Central Locomotive on the Blue Ash Subdivision Figure 5 CSX Industrial Track (Former B&0 Mainline) at Winton Road Figure 6 Cincinnati Riverfront with Produce Companies Figure 7 Railroads on the Cincinnati Riverfront Map (1976) Figure 8 Former Southwest Connection Piers Figure 9 Connection from the C&O Railroad Bridge to the Conrail Ditch Track Figure 10 Amtrak's Cardinal at the Cincinnati Union Terminal Figure 11 Chicago Hub Network - High Speed Rail Corridor Map Figure 12 Amtrak Locomotive at the CSX Queensgate Yard Locomotive Facility Figure 13 Conceptual Passenger Rail Corridor Figure 14 Southwest Connection Figure 15 Winton Place Junction Figure 16 Train on CSX Industrial Track Near Evans Street Crossing Figure 17 Potential Railroad Abandonments Map Figure 18 Proposed RlSP Projects Map Figure 19 RlSP Project Cost and Priority Executive Summary Introduction The railroad infrastructure in Cincinnati is critical for the movement of goods within the City, region, and country. It also provides the infrastructure for intercity passenger rail.