Crab Ripping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Species of the Genus Opisthotropis Günther, 1872 from Northern Laos (Squamata: Natricidae)

Zootaxa 3774 (2): 165–182 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3774.2.4 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:933179AB-E8DB-4785-9F79-E0D051E1E398 A new species of the genus Opisthotropis Günther, 1872 from northern Laos (Squamata: Natricidae) ALEXANDRE TEYNIÉ1, ANNE LOTTIER1, PATRICK DAVID*2, TRUONG QUANG NGUYEN3 & GERNOT VOGEL4 1 Société d'Histoire Naturelle Alcide d’Orbigny, 57 rue de Gergovie, F-63170 Aubière, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Reptiles & Amphibiens, UMR 7205 OSEB, Département Systématique et Évolution, CP 30, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet Road, Hanoi, Vietnam Current address: Department of Terrestrial Ecology, Zoological Institute, University of Cologne, Zülpicher Strasse 47b, D-50674 Cologne, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Society for Southeast Asian Herpetology, Im Sand 3, D-69115 Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] * corresponding author Abstract Two specimens, a male and a female, of the genus Opisthotropis Günther, 1872 were collected in a karst formation of northern Louangphabang (or Luang Prabang) Province, North Laos. These specimens are assigned to the genus Opisthotropis on the basis of their morphology, dentition and cephalic scalation. However, they differ from -

14787-April 06

An Inquiry-Based Exercise for Demonstrating Prey Preference in SNAKES AARON J. PLACE CHARLES I. ABRAMSON he use of live animals at all educational levels priate for students in middle school, high school, and Thas declined in recent years (Abramson et al., 1999c). college. Despite this trend, the curiosity many students have Snakes have much to recommend them for class- toward animals can be utilized to teach biological con- room study. They are readily captured in the field and cepts in the classroom. Live animals continue to be available from pet stores and biological supply houses used in the high school and undergraduate science such as Wards Scientific and Connecticut Valley classroom to teach physiology, ecology, and behavior Biological Supply House. Snakes can also be pur- (Abramson, 1990; Abramson et al., 1996; Abramson et chased from reptile dealers such as Glades Herp, Inc. al., 1999a,b; Darling, 2001; French, 2001; Rop, 2001). (http://www.gherp.com). In addition to wide availabil- The recent promotion of inquiry-based learning ity, snakes are easy to handle and maintain. Generally, techniques (Uno, 1990) is well suited to the use of ani- most snakes can be housed in appropriately-sized mals in the classroom. Working with living organisms plastic storage containers with a paper substrate and directly engages students and stimulates them to water available ad libitum. Appropriate food should be & INVESTIGATION INQUIRY actively participate in the learning process. Students offered every 7-10 days for large species and every 2-3 develop a greater appreciation for living things, the days for small species. -

NHBSS 061 1G Hikida Fieldg

Book Review N$7+IST. BULL. S,$0 SOC. 61(1): 41–51, 2015 A Field Guide to the Reptiles of Thailand by Tanya Chan-ard, John W. K. Parr and Jarujin Nabhitabhata. Oxford University Press, New York, 2015. 344 pp. paper. ISBN: 9780199736492. 7KDLUHSWLOHVZHUHÀUVWH[WHQVLYHO\VWXGLHGE\WZRJUHDWKHUSHWRORJLVWV0DOFROP$UWKXU 6PLWKDQG(GZDUG+DUULVRQ7D\ORU7KHLUFRQWULEXWLRQVZHUHSXEOLVKHGDV6MITH (1931, 1935, 1943) and TAYLOR 5HFHQWO\RWKHUERRNVDERXWUHSWLOHVDQGDPSKLELDQV LQ7KDLODQGZHUHSXEOLVKHG HJ&HAN-ARD ET AL., 1999: COX ET AL DVZHOODVPDQ\ SDSHUV+RZHYHUWKHVHERRNVZHUHWD[RQRPLFVWXGLHVDQGQRWJXLGHVIRURUGLQDU\SHRSOH7ZR DGGLWLRQDOÀHOGJXLGHERRNVRQUHSWLOHVRUDPSKLELDQVDQGUHSWLOHVKDYHDOVREHHQSXEOLVKHG 0ANTHEY & GROSSMANN, 1997; DAS EXWWKHVHERRNVFRYHURQO\DSDUWRIWKHIDXQD The book under review is very well prepared and will help us know Thai reptiles better. 2QHRIWKHDXWKRUV-DUXMLQ1DEKLWDEKDWDZDVP\ROGIULHQGIRUPHUO\WKH'LUHFWRURI1DWXUDO +LVWRU\0XVHXPWKH1DWLRQDO6FLHQFH0XVHXP7KDLODQG+HZDVDQH[FHOOHQWQDWXUDOLVW DQGKDGH[WHQVLYHNQRZOHGJHDERXW7KDLDQLPDOVHVSHFLDOO\DPSKLELDQVDQGUHSWLOHV,Q ZHYLVLWHG.KDR6RL'DR:LOGOLIH6DQFWXDU\WRVXUYH\KHUSHWRIDXQD+HDGYLVHGXV WRGLJTXLFNO\DURXQGWKHUH:HFROOHFWHGIRXUVSHFLPHQVRIDibamusZKLFKZHGHVFULEHG DVDQHZVSHFLHVDibamus somsaki +ONDA ET AL 1RZ,DPYHU\JODGWRNQRZWKDW WKLVERRNZDVSXEOLVKHGE\KLPDQGKLVFROOHDJXHV8QIRUWXQDWHO\KHSDVVHGDZD\LQ +LVXQWLPHO\GHDWKPD\KDYHGHOD\HGWKHSXEOLFDWLRQRIWKLVERRN7KHERRNLQFOXGHVQHDUO\ DOOQDWLYHUHSWLOHV PRUHWKDQVSHFLHV LQ7KDLODQGDQGPRVWSLFWXUHVZHUHGUDZQZLWK H[FHOOHQWGHWDLO,WLVDYHU\JRRGÀHOGJXLGHIRULGHQWLÀFDWLRQRI7KDLUHSWLOHVIRUVWXGHQWV -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Expanded Description of a Chinese Endemic Snake Opisthotropis Cheni (Serpentes: Colubridae: Natricinae)

Asian Herpetological Research 2010, 1(1): 57-60 DOI: 10.3724/SP.J.1245.2010.00057 Expanded Description of a Chinese Endemic Snake Opisthotropis cheni (Serpentes: Colubridae: Natricinae) LI Cao1, LIU Qin1 and GUO Peng 1, 2* 1 Department of Life Sciences and Food Engineering, Yibin University, Yibin 644000, Sichuan, China 2 Chendgu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan, China Abstract Based on seven newly-collected specimens, we provide an expanded description for the rare Chinese snake Opisthotropis cheni. The new specimens are consistent with the type series in scale counts and body dimensions. How- ever, two individuals lack yellow cross-bands that are apparent in the type specimens. A key to the ten Chinese species of Opisthotropis is provided. Keywords snake, Opisthotropis cheni, morphology, China 1. Introduction 070140, 071041, 071046-071050) (Table 1), collected from the Nanling National Nature Reserve in Ruyuan The genus Opisthotropis Gǘnther (1872) is comprised of County, Guangdong Province, China (Figure 1), were 17 currently recognized species, and is widely distributed morphologically examined in this work. The specimens in eastern, southern, and southeastern Asia (Uetz, 2010). were preserved in 8% formalin for initial fixation, and Members of this genus are all small aquatic snakes, later transferred to 75% ethanol. All specimens were de- mainly inhabiting rapidly flowing streams or small rivers. posited at Yibin University (YBU), Sichuan Province, Ten species of Opisthotropis occur in China (Zhao, China. 2006). Snout-vent length (SVL) and tail length (TL) were Zhao (1999) described Opisthotropis cheni based on measured using a meter ruler to the nearest millimeter, four specimens collected from Mt. -

Marine Reptiles Arne R

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Study of Biological Complexity Publications Center for the Study of Biological Complexity 2011 Marine Reptiles Arne R. Rasmessen The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts John D. Murphy Field Museum of Natural History Medy Ompi Sam Ratulangi University J. Whitfield iG bbons University of Georgia Peter Uetz Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/csbc_pubs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Copyright: © 2011 Rasmussen et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/csbc_pubs/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of Biological Complexity at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Study of Biological Complexity Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review Marine Reptiles Arne Redsted Rasmussen1, John C. Murphy2, Medy Ompi3, J. Whitfield Gibbons4, Peter Uetz5* 1 School of Conservation, The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2 Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America, 3 Marine Biology Laboratory, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences, Sam Ratulangi University, Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, 4 Savannah River Ecology Lab, University of Georgia, Aiken, South Carolina, United States of America, 5 Center for the Study of Biological Complexity, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, United States of America Of the more than 12,000 species and subspecies of extant Caribbean, although some species occasionally travel as far north reptiles, about 100 have re-entered the ocean. -

Zootaxa, Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Enhydris Clade

Zootaxa 2452: 18–30 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Phylogeny and biogeography of the Enhydris clade (Serpentes: Homalopsidae) DARYL R. KARNS1,2, VIMOKSALEHI LUKOSCHEK2,3, JENNIFER OSTERHAGE1,2, JOHN C. MURPHY2 & HAROLD K. VORIS2,4 1Department of Biology, Rivers Institute, Hanover College, Hanover, IN 47243. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Zoology, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605. E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA, 92697. E-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding author. E-mail [email protected] Abstract Previous molecular phylogenetic hypotheses for the Homalopsidae, the Oriental-Australian Rear-fanged Water Snakes indicate that Enhydris, the most speciose genus in the Homalopsidae (22 of 37 species), is polyphyletic and may consist of five separate lineages. We expand on earlier phylogenetic hypotheses using three mitochondrial fragments and one nuclear gene, previously shown to be rapidly evolving in snakes, to determine relationships among six closely related species: Enhydris enhydris, E. subtaeniata, E. chinensis, E. innominata, E. jagorii, and E. longicauda. Four of these species (E. subtaeniata, E. innominata, E. jagorii, and E. longicauda) are restricted to river basins in Indochina, while E. chinensis is found in southern China and E. enhydris is widely distributed from India across Southeast Asia. Our phylogenetic analyses indicate that these species are monophyletic and we recognize this clade as the Enhydris clade sensu stricto for nomenclatural reasons. Our analysis shows that E. -

Marine Reptiles: Adaptations, Taxonomy, Distribution and Life Cycles - A

MARINE ECOLOGY – Marine Reptiles: Adaptations, Taxonomy, Distribution and Life Cycles - A. Bertolero, J. Donoyan, B. Weitzmann MARINE REPTILES: ADAPTATIONS, TAXONOMY, DISTRIBUTION AND LIFE CYCLES A. Bertolero Department of Animal Biology, University of Barcelona, Spain J. Donoyan Documentary Centre, Ebro Delta Natural Park, Tarragona, Spain B. Weitzmann DEPANA, Project of Sustainable Management of Punta de la Mora, Tarragona, Spain Keywords: Reptile, marine, sea adaptations, sea turtles, Marine Iguana, sea snakes, salt balance, diving adaptation, thermoregulation, life cycle, conservation. Contents 1. Introduction 2. The fossil marine reptiles 3. Physiological adaptations to sea life 3.1. Salt and water balance 3.2. Respiration and diving adaptations 3.3. Thermoregulation 3.4. Locomotion 4. Sea Turtles 4.1. Morphology and adaptations 4.2. Life cycle and behaviour 4.3. Feeding 4.4. Predators 4.5. Habitat and distribution 4.6. Conservation 5. Marine Iguana 5.1. Morphology and adaptations 5.2. Life cycle and behavior 5.3. Feeding 5.4. PredatorsUNESCO – EOLSS 5.5. Habitat and distribution 5.6. ConservationSAMPLE CHAPTERS 6. Sea Snakes 6.1. Morphology and adaptations 6.2. Life cycle and behaviour 6.3. Feeding 6.4. Predators 6.5. Habitat and distribution 6.6. Conservation Acknowledgements Glossary ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) MARINE ECOLOGY – Marine Reptiles: Adaptations, Taxonomy, Distribution and Life Cycles - A. Bertolero, J. Donoyan, B. Weitzmann Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary The marine reptiles come from ancient terrestrial forms that eventually colonized the sea. The number of true marine species represents only 1% of all the reptile species that exist today. The true marine species are sea turtles, Marine Iguana and sea snakes. -

Fauna of Australia 2A

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 26. BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYLOGENY OF THE SQUAMATA Mark N. Hutchinson & Stephen C. Donnellan 26. BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYLOGENY OF THE SQUAMATA This review summarises the current hypotheses of the origin, antiquity and history of the order Squamata, the dominant living reptile group which comprises the lizards, snakes and worm-lizards. The primary concern here is with the broad relationships and origins of the major taxa rather than with local distributional or phylogenetic patterns within Australia. In our review of the phylogenetic hypotheses, where possible we refer principally to data sets that have been analysed by cladistic methods. Analyses based on anatomical morphological data sets are integrated with the results of karyotypic and biochemical data sets. A persistent theme of this chapter is that for most families there are few cladistically analysed morphological data, and karyotypic or biochemical data sets are limited or unavailable. Biogeographic study, especially historical biogeography, cannot proceed unless both phylogenetic data are available for the taxa and geological data are available for the physical environment. Again, the reader will find that geological data are very uncertain regarding the degree and timing of the isolation of the Australian continent from Asia and Antarctica. In most cases, therefore, conclusions should be regarded very cautiously. The number of squamate families in Australia is low. Five of approximately fifteen lizard families and five or six of eleven snake families occur in the region; amphisbaenians are absent. Opinions vary concerning the actual number of families recognised in the Australian fauna, depending on whether the Pygopodidae are regarded as distinct from the Gekkonidae, and whether sea snakes, Hydrophiidae and Laticaudidae, are recognised as separate from the Elapidae. -

Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : Palaeobiological and Behavioral Implications Remi Allemand

Endocranial microtomographic study of marine reptiles (Plesiosauria and Mosasauroidea) from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : palaeobiological and behavioral implications Remi Allemand To cite this version: Remi Allemand. Endocranial microtomographic study of marine reptiles (Plesiosauria and Mosasauroidea) from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : palaeobiological and behavioral implications. Paleontology. Museum national d’histoire naturelle - MNHN PARIS, 2017. English. NNT : 2017MNHN0015. tel-02375321 HAL Id: tel-02375321 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02375321 Submitted on 22 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Ecole Doctorale Sciences de la Nature et de l’Homme – ED 227 Année 2017 N° attribué par la bibliothèque |_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DU MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Spécialité : Paléontologie Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Rémi ALLEMAND Le 21 novembre 2017 Etude microtomographique de l’endocrâne de reptiles marins (Plesiosauria et Mosasauroidea) du Turonien (Crétacé supérieur) du Maroc : implications paléobiologiques et comportementales Sous la direction de : Mme BARDET Nathalie, Directrice de Recherche CNRS et les co-directions de : Mme VINCENT Peggy, Chargée de Recherche CNRS et Mme HOUSSAYE Alexandra, Chargée de Recherche CNRS Composition du jury : M. -

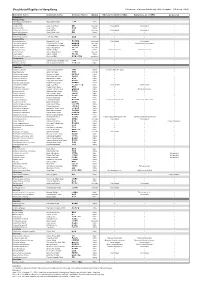

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

Kumejima Island, Japan

O . kikuzatoi through a series of field surveys as below. Current Herpetology 23(2): 73-80, December 2004 (c)2004 by The Herpetological Society of Japan Field Observations on a Highly Endangered Snake, Opisthotropis kikuzatoi (Squamata: Colubridae), Endemic to Kumejima Island, Japan HIDETOSHI OTA* Tropical Biosphere Research Center, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Okinawa 903-0213, JAPAN Abstract: The Kikuzato's brook snake, Opisthotropis kikuzatoi, is a highly endangered aquatic or semiaquatic species endemic to Kumejima Island of the Okinawa Group, Ryukyu Archipelago. Field studies were carried out for some ecological aspects of this species by visiting its habitat almost every month from April 1996 to March 1997. The results demonstrate that the snake is active almost throughout the year. It is also suggested that the snake tends to be diurnal in the warmer season, and nocturnal in the cooler season. Observations on a case of autonomous emergence onto the land, very slow growth, and predation on small crabs, are also provided. Key words: Opisthotropis kikuzatoi, Field census; Activity pattern; Body temper- ature; Kumejima Island INTRODUCTION broadleaf evergreen forest: see below), led Environment Agency of Japan assign O. The Kikuzato's brook snake Opisthotropis kikuzatoi to the highest Red List Category kikuzatoi, is a small colubrid species endemic (IA) as one of the two most critically endan- to Kumejima Island of the Okinawa Group, gered reptiles of Japan (Matsui, 1991; Ota, Ryukyu Archipelago. Since its original 2000). This snake is also protected by laws of description by Okada and Takara (1958: as a both the National Government of Japan and member of the genus Liopeltis), no more than the Prefectural Government of Okinawa (Ota, ten individuals have been known to science 2000).