Adam Possamai Introduction in 2004, Oberon Zell-Ravenheart, a Key Leader Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pangaia #47 1 BBIMEDIA.COM CRONEMAGAZINE.COM SAGEWOMAN.COM WITCHESANDPAGANS.COM

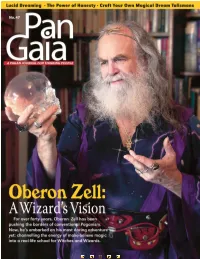

Autumn ’07 PanGaia #47 1 BBIMEDIA.COM CRONEMAGAZINE.COM SAGEWOMAN.COM WITCHESANDPAGANS.COM Magazines that feed your soul and liven your spirits. Navigation Controls Availability depends on reader. Previous Page Toggle Next Page Bookmarks First Page Last Page ©2010 BBI MEDIA INC . P O BOX 678 . FOREST GROVE . OR 97116 . USA . 503-430-8817 PanGaia: A Pagan Journal for Thinking People SPECIAL SECTION: DREAMS & VISIONS Dreamweavings: Craft Your Own Magical Talismans People have long made magical dreaming talismans: they weave fabric with mystical patterns; dry fragrant herbs to soothe and comfort; collect stones as sources of power. They twist sinew, thread, and limber twigs into fanciful shapes. In this article, you’ll learn how (and why) to make dreamcatchers and dream pillows. By Elizabeth Barrette … 29 Living in Dreamtime Australia has been a land apart for hundreds of thousands of years. An island continent of vast red deserts, shady eucalyptus groves, meandering rivers, high plains, coastal swamps, and turquoise oceans, her indigenous people know her very, very well. In their lore, they have always been there, traveling across sacred landscapes alive with songs and sto- ries that tell where to hunt and camp, what to eat, where to find water, who to marry, how to care for children and family, and how to honor the Ances- tors. On each step of the journey, the Ancestors of the Dreamtime guide their footsteps. By Mary Pat Mann … 37 Introduction to Lucid Dreaming: Let Your Imagination Take Flight Each night, we lay down our heads and pass into unconsciousness. Although everyone sleeps, (and dreams), few of us make conscious connections be- tween the world of dreams and that of waking real- ity. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara the Church

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Church of All Worlds: From an Invented Religion to a Religion of Invention A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Religious Studies by Damian Lanahan-Kalish Committee in charge: Professor Joseph Blankhom, Chair Professor Elizabeth Perez Professor David Walker June 2019 The thesis of Damian Lanahan-Kalish is approved. ____________________________________________________________ Elizabeth Perez ____________________________________________________________ David Walker ____________________________________________________________ Joseph Blankholm, Committee Chair May 2019 ABSTRACT The Church of All Worlds: From an Invented Religion to a Religion of Invention by Damian Lanahan-Kalish The Church of All Worlds is a Neo-Pagan religious group that took its inspiration from a Work of fiction. The founders of this church looked at the religion that Robert Heinlein created in his science fiction novel Stranger in a Strange Land and decided to make it a reality. This puts them squarely in the company of What Carole Cusack has termed “invented religions.” These are religions that seek validity in works that are accepted as fiction. The Church of All Worlds, noW over fifty years old, has groWn beyond its science fiction roots, adopting practices and beliefs that have made them an influential part of the modern Pagan movement. Though fiction no longer plays as strong a role in their practice, they have remained dedicated to an ethic of invention. Through ethnographic research With Church members in Northern California, this paper explores hoW this ethic of invention manifests in official Church history, the personal relationships of members, and the creation of public rituals. -

Examining Occult Infrastructure DISSERTATION

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Modern Magics: Examining Occult Infrastructure DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Informatics by Richard Aubrey Slaughter, IV Dissertation Committee: Professor Geoffrey Bowker Chair Professor Matthew Bietz Professor Theresa Tanenbaum Professor Aaron Trammell 2020 © 2020 Richard Aubrey Slaughter, IV DEDICATION To my interviewees and interlocutors Family and friends My deepest gratitude ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii VITA viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ix INTRODUCTION 1 Examining Infrastructure 3 Studying Magic 7 The Occult 9 Human Relations to the Occult 16 METHODS 19 Corpora Content and Data Collection 19 Student Answers Corpus 19 Magical Practitioner Interviews Corpus 22 Informatics Corpus 25 Control Corpus 26 Limitations in Corpora and Data Collection 26 Automated Qualitative Processing and Distant Reading Methods 30 Manual Qualitative Processing and Close Reading Methods 31 Limitations to Qualitative Processing and Analysis 32 CHAPTER 1: STUDENT DATA 33 iii What is a Relationship With Infrastructure Like? Touching the Elephant 40 Legs Like a Tree: Natural Metaphors in Human/Infrastructural Relations 41 Trunk like a Snake: Anthropomorphic Metaphors in Human/Infrastructural Relations 43 Side Like a Wall: Architectural Metaphors in Human/Infrastructural Relations 48 The Elephant in The Room: Metaphors in Human/Infrastructural Relations 50 Infrastructural Fantasies: Imaginative Conceptions of -

The Common Book of Witchcraft and Wicca

COVER IMAGE Druid's Temple - a Mini Stonehenge by Chris Heaton Source: http://www.geograph.org.uk/reuse.php?id=1419678 Image Copyright Chris Heaton. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 2.0 Generic License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/ The Common Book of Witchcraft and Wicca from the Ancestors The initial version of “The Common Book of Witchcraft and Wicca” is copyrighted to Witch School, International, Inc. © 2014 for the layout, structure, and specific print editions thereof. The “book” itself, i.e. all of the individual content elements, is being published under a Creative Commons license (see below). This version was designed, produced, and to some extent edited by Eschaton Books, and is being published under these ISBNs: EBOOK - 978-1-57353-902-9 PAPERBACK - 978-1-57353-903-6 HARDCOVER - 978-1-57353-904-3 For more information on obtaining copies of the paperback print edition, please visit: All the individual elements of this book are being published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Li- cense - http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ - which means that it is “Approved for Free Cultural Works” by Cre- ative Commons. Pagans don't have a holy book, they have libraries. - Phaedra Bonewits TABLE OF CONTENTS xiii Foreword Don Lewis xvii Preface Ed Hubbard 1 Theagenesis Oberon Zell 14 Art: - “Creation” Don Lewis 15 The Nature of the Soul Don Lewis 18 Chant: - “Elemental” Correllian Tradition 19 Human Heritage and the Goddess Abby Willowroot 22 Chant - “Daughter of Darkness” Correllian Tradition 23 The Difference Between Modern Wicca and Oldline Witchcraft A.C. -

Invented Religions : Faith, Fiction, Imagination / Carole M Cusack

Invented Religions Imagination, Fiction and Faith Carole M. Cusack INVENTED RELIGIONS Utilizing contemporary scholarship on secularization, individualism, and consumer capitalism, this book explores religious movements founded in the West which are intentionally fictional: Discordianism, the Church of All Worlds, the Church of the SubGenius, and Jediism. Their continued appeal and success, principally in America but gaining wider audience through the 1980s and 1990s, is chiefly as a result of underground publishing and the internet. This book deals with immensely popular subject matter: Jediism developed from George Lucas’ Star Wars films; the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, founded by 26-year-old student Bobby Henderson in 2005 as a protest against the teaching of Intelligent Design in schools; Discordianism and the Church of the SubGenius which retain strong followings and participation rates among college students. The Church of All Worlds’ focus on Gaia theology and environmental issues makes it a popular focus of attention. The continued success of these groups of Invented Religions provide a unique opportunity to explore the nature of late/post-modern religious forms, including the use of fiction as part of a bricolage for spirituality, identity-formation, and personal orientation. Ashgate NeW RelIGIoNS Series Editors: James R. Lewis, University of Tromsø, Norway George D. Chryssides, Senior lecturer in Religious Studies, University of Wolverhampton, UK The popularity and significance of New Religious Movements is reflected in the explosion of related articles and books now being published. This Ashgate series offers an invaluable resource and lasting contribution to the field. Invented Religions Imagination, Fiction and Faith CARole M. -

Spring Fever 2

Grey School of Wizardry Spring Equinox Newsletter Volume 1, Issue 2 Managing Editor: Lady Ravenweed March 20, 2005 Co-Editor: Moonwriter Published by the Grey School Press “All the quarterly joy that’s fit to print.” The Vernal Equinox takes place on Official weatherworking report: Sunday, March 20, at 4:33 AM (pacific Wrap up in a warm cloak, and don’t forget the umbrella! time, USA). Merry meet, everyone! It's been a wonderful winter here at the Grey School and we’re all looking forward to spring. In this edition we’re proud to feature a newsletter written almost completely by Grey School students. Enjoy! (Please send comments, submissions, or suggestions for future editions to [email protected].) What’s New at the Grey School? The Grey School Store—Magick Alley—is now operating under the leadership of volunteer shopkeeper Lion Bane (Flames Lodge). If you haven’t visited the store for a while, stop in and check out the new selections of books, wands, magickal journals, and more! The Prefect System is underway. All new Prefects will take a special class called “Leadership 101,” offered in the Department of Lifeways. Prefects also have their own e-forum, the “Prefect Lounge,” created by Aaran (Stones Lodge). Look for the Prefects to have an ever-increasing role in Grey School operations, and feel free to ask your favorite Prefect any questions you might have. The Prefects will soon be running a “Name the Newsletter” contest. Start thinking about this now, and stay tuned for updates. A Grey School Handbook is almost completed and will soon be made available to students. -

Sea, Land, Sky: a Dragon Magick Grimoire, 2003, Parker J. Torrence, Three Moons Media, 2003

Sea, Land, Sky: A Dragon Magick Grimoire, 2003, Parker J. Torrence, Three Moons Media, 2003 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/11wQ9qq http://goo.gl/RN21r http://www.goodreads.com/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&query=Sea%2C+Land%2C+Sky%3A+A+Dragon+Magick+Grimoire Sea, Land, Sky: A Dragon Magick Grimoire is about Dragon Magick, but even more, it is about the realms where magick can, and should take place. In Part I, Here There Be Dragons, you are introduced to the world of Dragon Magick, and the Realms of Sea, Land, and Sky. Here there be dragons, and here you will learn the mystical art of meeting them, and how to incorporate them into your magickal rituals. In Part II, The Book of Dragon Shadows, you will discover a miscellany of rituals, spells, and formulas -- everything needed to practice the art of Dragon Magick. DOWNLOAD http://t.co/Z4cxNWJwA3 http://bit.ly/WxcwJd Dragonlore From the Archives of the Grey School of Wizardry, Ash Dekirk, Oberon Zell-Ravenheart, 2006, Body, Mind & Spirit, 222 pages. Nearly every culture on Earth has myths of dragons. This richly-illustrated book examines dragons in modern culture and the natural world, including the pterodactyl and other. The Element How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything, Ken Robinson, Lou Aronica, Jan 8, 2009, Self-Help, 288 pages. A New York Times-bestselling breakthrough book about talent, passion, and achievement from the one of the world's leading thinkers on creativity and self- fulfillment. The. Witches , Peggy J. Parks, 2008, Juvenile Nonfiction, 96 pages. Discusses the history of witchcraft, from ancient god and goddess worship to modern wicca, witch-hunts in Europe and America, the punishments suspected witches received, and. -

The Grey School of Wizardry in 2004 Oberon Zell-Ravenheart Established the Grey School of Wizardry, a Magical Education Syste

C. Cusack, “The Grey School of Wizardry” Forthcoming in: E. Asprem (ed.), Dictionary of Contemporary Esotericism Preprint manuscript of: C. Cusack, “The Grey School of Wizardry”, Dictionary of Contemporary Esotericism (ed. E. Asprem), Leiden: Brill. Archived at ContERN Repository for Self-Archiving (CRESARCH) https://contern.org/cresarch/cresarch-repository/ Aug. 13, 2018. The Grey School of Wizardry In 2004 Oberon Zell-Ravenheart established the Grey School of Wizardry, a magical education system drawing upon J. K. Rowling’s novels about the boy wizard Harry Potter. In Rowling’s alternate England, the children of wizard families are educated at Hogwarts, where they study “Spells”, “Potions”, and “Defence Against the Dark Arts”, among other subjects. The Grey School has a seven-year programme (like Hogwarts). The four houses of Slytherin, Gryffindor, Hufflepuff and Ravenclaw are mirrored by four houses named for the elementals associated with the four quarters, sylphs, salamanders, undines and gnomes (air, fire, water and earth). The Grey School has Potteresque features, such as the “Magick Alley” site where textbooks and school equipment may be purchased, which is similar to Diagon Alley in Harry Potter’s London, where wands and robes, spell ingredients and companion animals (owls, cats, and toads) can be acquired (Cusack 2010, 73-76). Since 2004 textbooks aimed at making wizardry and magic attractive and interesting to children and young adults have appeared. The first was Grimoire for the Apprentice Wizard (2004), which contains material on magical arts, conducting rituals, cosmology, wizards of history (including Éliphas Lévi, Charles Godfrey Leland, Aleister Crowley and Gerald Gardner), and a multitude of other subjects, assembled into seven blocks of study (Zell Ravenheart 2004). -

Grey School Conclave BY: MOONWRITER

Whispering Grey Matters Spring 2006 rey School O F W I Z A R D R Y “A MAGICKAL WHISPER SPOKEN IN EVERY WORD.” G 02 GREY SCHOOL OF WIZARDRY 07 NEWS 17 OPINION 18 INTERNATIONAL ISSUE 2 ! VOLUME 2 ! SPRING 2006 18 ARTS & CULTURE MaW h its p etr ien g Grr e ys A COOPERATIVE EFFORT OF TEACHERS, STUDENTS, AND WIZARDS DEVELOPING A SOUND FOUNDATION OF WIZARDRY FOR ALL G R E Y S C H O O L O F W I Z AR D R Y FIRST EVER: Grey School Conclave BY: MOONWRITER What has 120 legs, NEW CLASSES, MAJORS, & Faculty participants include Crow Dragontree, Morgan Felidae, MINORS! 60 wands, and a Rainmaker, WillowRune, and Moonwriter. Aaran and Kalla, the current Lodge Captain and Vice Lodge Captain, will also attend. really big bubble The Grey School curriculum con- tinues to expand. In the past several shield? This is a camping experi months, dozens of new classes have The participants at the First ence—everyone will be been added. One Major—the Major Grey School Conclave! tenting under the stars in Lore—is fully developed and and cooking their own ready to be earned, with a Major in On July 20-23, 2006, sixty meals, and everyone will Wortcunning in progress. In addi- Grey School students, faculty, supply their own gear, tion, several Minors—Lore, Nature friends, and family will meet at food, etc. Cost is esti Studies, Beast Mastery, and Wort- Silver Falls State Park mated at $25/person. cunning—are available now to (Oregon) for the Oregon Con- clave. -

Prom Photos Band Speech • Robotics Update • Summer• Prom Break Dresses Ideas and MORE

Issue 4 Volume 57 May 18, 2015 THE Saydelphic IN THIS ISSUE: Prom Photos Band Speech • Robotics Update • Summer• Prom Break Dresses Ideas AND MORE Saydel High School / 5601 NE 7th Street / Des Moines, IA Student Government by Katie Coy Saydel High School’s Student ry’s memory. To extend their work “I also enjoy being able to have the Government has been up to some outside of Saydel’s community, opportunity to go to leadership con- amazing things! Student government over the last month student gov- ferences and take what I learn there is a student-led council consisting of ernment has been holding a Jeans and implement it into my daily life.” for Teens drive at the school where freshmen through seniors. Mrs. Student government is a students and adults can donate Brenda Brown is the current student great club for students who want to jeans of good quality. These jeans government sponsor. Mrs. Brown become leaders. Make sure you are then given to those in need and helps the students organize the fund- thank Saydel High School’s Student those who cannot afford new jeans raisers and supports them. Student Government members for all that each winter. government meets at least once a they do, and remember anyone can month to discuss projects that give “I enjoy being a part of stu- join student government if they wish back to Saydel’s community and oth- dent government because I am to! If you’re interested in becoming a er communities. able to know and have a say on member of this amazing group, con- One of the most recent pro- things that are going on around the tact Mrs. -

The Witches' Book of the Dead Raven Grimassi, Christian Day - Download Pdf Free Book

(PDF) The Witches' Book Of The Dead Raven Grimassi, Christian Day - download pdf free book The Witches' Book of the Dead pdf read online, online free The Witches' Book of the Dead, Read Best Book Online The Witches' Book of the Dead, The Witches' Book of the Dead Download PDF, Download The Witches' Book of the Dead E-Books, Read The Witches' Book of the Dead Online Free, Read Online The Witches' Book of the Dead E-Books, Read The Witches' Book of the Dead Online Free, Read Online The Witches' Book of the Dead Book, Download The Witches' Book of the Dead E-Books, The Witches' Book of the Dead Free PDF Online, Free Download The Witches' Book of the Dead Full Version Raven Grimassi, Christian Day, The Witches' Book of the Dead Free Download, Read The Witches' Book of the Dead Full Collection, Free Download The Witches' Book of the Dead Full Version Raven Grimassi, Christian Day, The Witches' Book of the Dead Popular Download, The Witches' Book of the Dead Ebook Download, PDF The Witches' Book of the Dead Full Collection, Download pdf The Witches' Book of the Dead, Read The Witches' Book of the Dead Full Collection, CLICK FOR DOWNLOAD kindle, pdf, epub, mobi Description: R No Man's Sky, Not Real Time - No Longer It Will Be By Matt Gourr I don't think much has come up about where it really is, he said in disbelief when asked if his parents would be upset with what they say next time the young star opens their eyes to see pictures from TV or play him there for two-and-AHHHHHH I do. -

Claiming Identity Through a Reading of Fantasy Withcraft Jessica Satterwhite Gray Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Modern myth in performance: claiming identity through a reading of fantasy withcraft Jessica Satterwhite Gray Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gray, Jessica Satterwhite, "Modern myth in performance: claiming identity through a reading of fantasy withcraft" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 225. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/225 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MODERN MYTH IN PERFORMANCE: CLAIMING IDENTITY THROUGH A READING OF FANTASY WITCHCRAFT A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Theatre by Jessica Satterwhite Gray B.A., University of North Carolina, 1999 M.A., Florida State University, 2001 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was born from the love and support of many. I give my sincere thanks… To my beloved Rhye and sweet girl Ariana for giving me the space and support to manifest this work. May our family grow in love and prosperity. To my mom and dad for raising me to be a spiritual seeker. May the love and understanding between us increase. To the Witches, Pagans and others who are forging ground in this new religious tradition.