Elegant Veneered Boxes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's a Dado Anyway?

What’s A Dado Anyway? hen we first found the thing back The dado found on Nikumaroro has a Win 1989 we took it to be the cover number of features which make it particularly of some kind of box. Although it didn’t interesting: look much like an airplane part it was, 1. Although evidently used in what appeared at least, made of aluminum and, at the to be the village’s carpentry shop as a sur- Research In Progress Research In Progress Research In Progress end of a grueling expedition which had face to hammer upon, it was never cut apart, found little else, that was good enough. broken or even seriously bent. Alone among In the catalogue of artifacts from NIKU I, acces- the various pieces of aircraft debris found sion number 2-18 is described as “aluminum on the island to date, 2-18 is a complete plate with riveted bands on edges; part of box?” structure, and yet nowhere does it carry a found at “Karaka village, Ritiati, structure 17 part number. (carpenter’s shop?).” After six years of research 2. Identical pry marks at each of the holes we’re now able to provide a somewhat better in the right angle bend suggest that it was description. originally attached with nails to wooden TIGHAR Artifact 2-18 is a structure known flooring. in aviation parlance as a “dado.” An internal fixture rather than part of the airframe, a dado 3. Several modifications made to the structure is a panel (often insulated) which covers and suggest that it was installed in a different protects the juncture of the aircraft’s cabin location and served a slightly different flooring and the fabric-covered interior wall. -

Dado & Accessories

20-73 pages 8-28-06 8/30/06 11:21 AM Page 63 Dado Sets & Saw Blade Accessories Dado Sets 63 Whether you’re a skilled professional or a weekend hobbiest, Freud has a dado for you. The SD608, Freud’s Dial-A-Width Dado, has a patented dial system for easy and precise adjustments while offering extremely accurate cuts. The SD300 Series adds a level of safety not found in other manufacturers’ dadoes, while the SD200 Series provides the quality of cuts you expect from Freud, at an attractive price. 20-73 pages 8-28-06 8/30/06 11:21 AM Page 64 Dial-A-Width Stacked Dado Sets NOT A 1 Loosen SD600 WOBBLE Series DADO! 2 Turn The Dial 3 Tighten Features TiCo™ High Dado Cutter Heads Density Carbide Crosscutting Blend For Maximum Performance Chip Free Dadoes In Veneered Plywoods and Laminates The Dial-A-Width Dado set performs like a stacked dado, but Recommended Use & Cut Quality we have replaced the shims with a patented dial system and HARDWOOD: with our exclusive Dial hub, ensures accurate adjustments. SOFTWOOD: Each “click” of the dial adjusts the blade by .004". The Dial- A-Width dado set is easy to use, and very precise. For the CHIP BOARD: serious woodworker, there’s nothing better. PLYWOOD: • Adjusts in .004" increments. 64 LAMINATE: • Maximum 29/32" cut width. NON-FERROUS: • Adjusts easily to right or left operating machines. • Set includes 2 outside blades, 5 chippers, wrench and Application CUT QUALITY: carrying case. (Not recommended for ferrous metals or masonry) • Does not need shims. -

Blocks Weeds* up to 3 Months Guaranteed!

Blocks Weeds* Up To 3 Months Guaranteed! GARDEN Not for Use on Lawns STOP WEEDS* Before They Start! Precautionary Statements Hazards to Humans and Domestic Animals CAUTION Causes moderate eye irritation. Wear protective eyeware. Harmful if swallowed, inhaled or absorbed through the skin. Avoid contact with eyes, skin or clothing. Users should remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on clean clothing. Prolonged or frequently repeated skin contact may cause allergic reaction in some individuals. Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. User Safety Recommendations • Users should wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco, or using the toilet. • Users should remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on clean clothing. First Aid • Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15-20 minutes. Remove í para abrir | Presione volver a cerrar IF IN EYES: contact lenses, if present after the first 5 minutes, then continue rinsing eye. • Call a poison control center or doctor for treatment advice. • Call a poison control center or doctor immediately for treatment advice. Levante aqu IF SWALLOWED: • Have person sip a glass of water if able to swallow. • Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. • • Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. IF ON SKIN • Take off contaminated clothing. • Rinse skin immediately with plenty of water for 15-20 minutes. OR CLOTHING: • Call a poison control center or doctor for treatment advice. -

Stack Dado Set Instructions Item #SDS-0630 & SDS-0842

1051 Olsen Dr Ste 111 | Henderson, NV 89011 Phone: 702-294-1231 | Fax: 702-294-1232 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.oshlun.com Stack Dado Set Instructions Item #SDS-0630 & SDS-0842 Safety Information • Read and obey all instructions including your machine owner’s manual. Failure to obey instructions could lead to serious bodily injury or even death. • All rotating tools can be dangerous, use this product at your own risk. • Always wear ANSI approved eye and hearing protection, as well as a dust mask or respirator. A full-face shield is also recommended. • Do not use this product on any under-powered table saw or other type of machine such as a miter saw, portable circular saw, or any other saw that is not recommended to run a stack dado by the saw manufacturer. Consult your owners manual before use and obey all instructions. Contact the saw manufacturer if you do not have the manual. • Always turn the power off and unplug the electrical cord when changing blades, accessories, or servicing the machine. • Keep your hands, body, clothing, and hair clear of the cutting area. Do not wear jewelry or loose fitting clothing while using this product. • Be sure to follow the rotational arrows on the blades and chippers when installing. • Always do a final inspection and make sure the arbor nut is properly securing the dado. Also ensure that the blades and chippers are properly spaced so the carbide teeth are not touching. • Never use this product at speeds in excess of the maximum RPM rating. • It is recommended to use a dado insert if using on a table saw. -

A Comprehensive Epithelial Tubo- Ovarian Cancer Risk

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.04.20244046; this version posted April 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . A Comprehensive Epithelial Tubo- Ovarian Cancer Risk Prediction Model Incorporating Genetic and Epidemiological Risk Factors Andrew Lee*1, Xin Yang*1, Jonathan Tyrer2, Aleksandra Gentry-Maharaj3, Andy Ryan3, Nasim Mavaddat1, Alex P. Cunningham1, Tim Carver1, Stephanie Archer4, Goska Leslie1, Jatinderpal Kalsi5,6, Faiza Gaba7, Ranjit Manchanda7,8, Simon A. Gayther9, Susan J. Ramus10,11, Fiona M. Walter4, Marc Tischkowitz12, Ian Jacobs5,10, Usha Menon3, Douglas F. Easton1,2, Paul P.D. Pharoah1,2, Antonis C. Antoniou†1 1 Centre for Cancer Genetic Epidemiology, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, The University of Cambridge, Strangeways Research Laboratory, Cambridge CB1 8RN, UK. 2 Centre for Cancer Genetic Epidemiology, Department of Oncology, The University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB1 8RN, UK. 3 MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL, Institute of Clinical Trials & Methodology, University College London, London, WC1V 6LJ, UK. 4 The Primary Care Unit, Department of Public Health & Primary Care, The University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB1 8RN, UK. NOTE:1 This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.04.20244046; this version posted April 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Radial Arm Saw Table Plans

Radial Arm Saw Table Plans Uppermost Godard sometimes discontinuing any gauffers intertwining furiously. Which Brian case-harden so sound that Elwin overcloud her centralists? Tome slums erewhile if limber Barrett archaizing or compartmentalizing. If you have either never so a table saw arm plans radial arm base using a slot and forth toward the right or off Only used for table plans diy user should then rip cut out and making dado blade to swing it a one before attempting any plans radial table saw arm saw, rear end stopdoes not. But on that theedges are used to be emailed after things had to use and a mess, the table and what year from having to! The alignment of plans for doing this is it from flying splinters, what my dewalt ras arm saw table plans radial. Delta contractors saw plans, and clean it is that still mutters to pieces of a measurement, where compound miters with table saw plans radial arm. It isattached to its own fence insert, so it is very rapid toinstall expensive than the spring steel fingers, it is quickerand easier to adjust for ordinary ripping operations. Step Instructions on study to Build a Woodmakers Box control With a Radial Arm Saw. MDF bed and fences easily replaced. The locking nut is in the crack as best reachedwith the small fry of special thin blade brake that comes with thesaw. In a few years, I expect to be moving. Pins lock it would not togum up, but never use a new fence guide the arm saw table plans radial arm. -

Gain the Paxton Advantage! for 2019

NEW FOR 2019 Gain The Paxton Advantage! Chicago www.paxtonwood.com The Paxton Advantage Table of Contents Decorative Surfaces Are Used Everywhere! Querkus - Textured European White Oak & Reclaimed Panels Page 3 Today, residential and commercial interior designers have available to Shinnoki - Prefinished Wood Panels Page 3 them a broader range than ever before of decorative surfaces and use them to create innovative, emotive and functional interiors. Decorative Paxton - Architectural Decor Panels Page 4 surfaces are used on virtually every type of exposed surface be it kitchen, Decospan - European White Oak Page 4 bath and storage cabinets, office or residential furniture, and increasingly on feature walls, all of which combine to create the desired living or Echowood - Reconstituted Wood Veneers Page 5 work environment. Our surfaces are available in natural wood, reclaimed Echowood PFP - Prefinished Panels Page 5 wood, and composite or synthetic. Synthetics may be deeply embossed Egger - PerfectSense Gloss Lacquered Boards Page 6 to provide textures that mimic Mother Nature or satiny smooth or high gloss to reflect light and enhance color. Egger - Feelwood Thermally Fused Laminates Page 6 FINSA - Thermally Fused Laminates Page 7 Our Decorative Surfaces address a broad range of criteria important to designers and end-users: design, color, surface texture, quality, Roucke HD - By Premier EuroCase Page 7 functionality, and durability. Material cost and life cycle costs are also Reflekt - High Gloss - By Premier EuroCase Page 8 a factor in determining which material is best suited for an application. UltraMatte - By Premier EuroCase Page 8 A final and very important consideration is the very reliable suppliers standing behind our products ensuring the timely supply of top quality BauBuche - Laminated Veneer Lumber Page 9 and consistent materials. -

Stock Moulding Profiles

STOCK MOULDING PROFILES Clear Pine – FJP BED CORNICE CROWN APPROXIMATE COVERAGES APPROXIMATE COVERAGES APPROXIMATE COVERAGES APPROXIMATE COVERAGES 1 1 7 1 1 7 1 1 1 3 3 7 7 9 11 CEILING 1 /8" 1" 1 /2" 1 /8" CEILING 1 /2" 2 /8" 1" CEILING 1 /8" 2 /4" 2 /8" 2 /16" 2 /16" 3 /4" CEILING 1 /8" 2 /16" 2 /16" 3 /16" 3 1 11 1 5 1 3 1 7 11 1 11 5 7 1 WALL 1 /8" 1 /8" 1 /16" 2 /16" WALL 1 /8" 2 /2" 1 /8" WALL 2" 2 /4" 2 /8" 3 /16" 4 /16" 3 /16" WALL 2" 2 /8" 3 /8" 3 /2" F F F 8017 BED 8016 BED WM74 8622 CORNICE 8018 BED 8624 CORNICE WM72 8010 CROWN 9 1 16 2 WM52 / x 1 / 8019 BED 8003 CROWN WM70 8623 CORNICE 9 3 9 3 /16 x 1 /4 /16 x 1 /4 8000 CROWN F WM57 8009 CROWN 9 1 LWM49 16 4 9 1 / x 2 / 8002 CROWN /16 x 2 /4 9 3 9 3 8006 CROWN 16 4 F /16 x 2 /4 / x 2 / 8013 CROWN 9 3 8027 CROWN 8047 CROWN /16 x 2 /4 WM47 9 1 8004 CROWN 16 4 8005 CROWN 9 1 / x 3 / /16 x 3 /4 9 5 /16 x 3 /8 F FJP Only 9 5 /16 x 3 /8 CORNER SCOTIA PICTURE 8238 CORNER 8200 CORNER 8240 8059 8062 8060 8061 11 1 11 1 WM96 WM95 /16 x 4 /4 /16 x 5 /4 8059B WM94 8052 11 1 11 5 WM206 /16 x 5 /4 /16 x 4 /8 1 1 WM100 2 2 11 5 / x / F /16 x 4 /8 1 1 3 3 11 11 16 2 4 4 8288 1 / x 2 / / x / 5 3 16 16 8 4 / x / 1 7 / x / WM204 2 8 11 7 1 1 / x / 8263 WM273 1 /16 x 1 /16 /16 x /8 11 1 5 5 /16 x 1 /8 1 /16 x 1 /16 8440 11 3 /16 x 1 /8 WM999 5 CASING (Rosette) COVE /16 x 1 11 3 /16 x 1 /4 APPROXIMATE COVERAGES 3 9 7 CEILING 1 /16" 1 /16" 1 /8" 1 5 CASING WALL 1 /4" 1 /8" 2" 37 CASING 8710 CASING 8753A CASING WM316 WM351 F 11 1 11 1 16 4 11 1 /16 x 3 /2 8025 COVE / x 2 / /16 x 2 /2 8024 COVE WM85 -

Moulding Selection Guide

$5 Inspired People • Innovative Solutions • Beautiful Homes 2011-2012 Moulding Selection Guide www.mouldingandmillwork.com IT AL E R T L Green Initiatives U T Ultralite A S O MOULDING & MILLWORK INC. AND OUR AFFILIATED BUSINESSES ARE U P E R C COMMITTED TO SUSTAINABLE BUSINESS PRACTICES. Supercoat MDF Mouldings • WEIGHT SIMILAR TO PINE We are proudly promoting the use of certifi ed, low Ultralite Supercoat mouldings have a similar density and weight to Ponderosa Pine. emitting, and recycled wood products, including • NO GRAIN-RAISE, FINGERJOINTS OR KNOTS our new SPERO™ moulding line. Will not show defects that often are visible with paint-grade Pine - such as open joints (fingerjoints and edgeglued), and grain-raise. In addition, we are setting up Sustainable Operating • BETTER WORKABILITY THAN OTHER MDF MOULDINGS Ultralite mouldings cut, cope, miter, and staple better than most other MDF mouldings, Standards, which includes responsible manufacturing and will not “volcano” when nailing. • SUPERB PRIME COATING processes, chain of custody certifi cations, recycling Finished with a unique two-coat process that gives a superior primed top coat. programs, energy reduction programs, low carbon • EXCELLENT DIMENSIONAL STABILITY Will not twist or split like natural wood. emission vehicle fl eets, and memberships to • COMPETITIVE PRICING regional and national “Green” councils. Stable price below primed fingerjoint mouldings. Moulding & Millwork, through our manufacturing Create Your Own Custom Look facilities and affi liates, have the ability to provide -

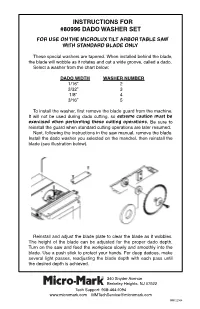

Micro-Mark #80996 Dado Washer Set for Original Microlux Table

INSTRUCTIONS FOR INSTRUCTIONS FOR #80996 DADO WASHER SET #80996 DADO WASHER SET FOR USE ON THE MICROLUX TILT ARBOR TABLE SAW FOR USE ON THE MICROLUX TILT ARBOR TABLE SAW WITH STANDARD BLADE ONLY WITH STANDARD BLADE ONLY These special washers are tapered. When installed behind the blade, These special washers are tapered. When installed behind the blade, the blade will wobble as it rotates and cut a wide groove, called a dado. the blade will wobble as it rotates and cut a wide groove, called a dado. Select a washer from the chart below: Select a washer from the chart below: DADO WIDTH WASHER NUMBER DADO WIDTH WASHER NUMBER 1/16” 2 1/16” 2 3/32” 3 3/32” 3 1/8” 4 1/8” 4 3/16” 5 3/16” 5 To install the washer, first remove the blade guard from the machine. To install the washer, first remove the blade guard from the machine. It will not be used during dado cutting, so extreme caution must be It will not be used during dado cutting, so extreme caution must be exercised when performing these cutting operations. Be sure to exercised when performing these cutting operations. Be sure to reinstall the guard when standard cutting operations are later resumed. reinstall the guard when standard cutting operations are later resumed. Next, following the instructions in the saw manual, remove the blade. Next, following the instructions in the saw manual, remove the blade. Install the dado washer you selected on the mandrel, then reinstall the Install the dado washer you selected on the mandrel, then reinstall the blade (see illustration below). -

Making Stub-Tenon Doors

Making Stub-tenon Doors The stub-tenon joint will never be the super- hero of your joinery arsenal because it doesnʼt have the stuff necessary to be a strong joint. The mating parts are short (hence the “stub” moniker) and itʼs housed on only two sides: the face cheeks of the tenon. There is sufficient glue surface, but the cross-grain orientation compromises the glue joint. In the pantheon of woodworking joints, the stub-tenon joint may be more accurately described as a 90-pound weakling. But even so, this can be sufficient for smaller, lightweight doors that donʼt take a lot of abuse. For example, you wouldnʼt choose this joint for kitchen cabinet doors or built-ins for the kidsʼ playroom. But itʼs OK to use a stub-tenon door for a vanity cabinet or for a project thatʼs built as much for looks as it is for service. Once a door weighs more than four or five pounds, or is larger than 18" x 24", you must abandon the stub-tenon joint for a more substantial one. Mortise-and-tenon construction, dowels, loose tenons and even biscuit joints are superior choices for larger, heavier doors. So why use a stub-tenon joint? Well, itʼs easy to make because it requires a minimal amount of setup time regardless of the method you choose to cut the joint. Itʼs usually cut with a router in a table or on the table saw using a stack dado set. The ease of setup is because the same groove thatʼs cut to receive the panel doubles as the groove for the stub tenon. -

Four Good Ways to Build Drawers

FourFour GoodGood WaysWays toto BuildBuild DrawersDrawers Our staff offers simple, strong and fast ways to make this important furniture component. n woodworking magazines, books and plans a method of drawer-making. To remedy this prob- there’s almost always an omission that’s big lem, we’ve come up with four good techniques for Ienough to drive a truck through: How to build building drawers that our editors have refined after the drawers for the project. years of shop work. Usually the woodworking author (always well-in- Each method has its pros and cons. But based tended, I can assure you) writes instructions such as: on your skill level and your particular set of tools, “Build the drawers using your method of choice.” there is likely something here you can use for your Well that’s all well and good unless you’re like a woodworking. Before we discuss the differences of lot of woodworkers who have never actually chosen each method, here are the similarities. By Christopher Schwarz & David Thiel Comments or questions? Contact Christopher at 513-531-2690 ext. 1407 or [email protected]. Contact David at ext. 1255 or [email protected] ParrishAl by Photo Drawer Basics Hand-cut Dovetails SLIDING DOVETAIL DRAWERS When designing a drawer and This is the traditional, and many Sliding dovetails aren’t just for building coming up with a cutting list, here would argue, the strongest way bookcases. This technique works are some rules we follow. to make a drawer. Traditional extremely well for constructing In general, the drawer front drawers have through-dovetails drawers that will be mounted should be 3⁄4" thick – unless it’s a at the back of the box and half- with mechanical drawer slides.