Red Media, Blue Media: Evidence of Ideological Selectivity in Media Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019

PUBLIC LAW 116–23—JUNE 25, 2019 BLUE WATER NAVY VIETNAM VETERANS ACT OF 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:12 Sep 30, 2019 Jkt 089139 PO 00023 Frm 00001 Fmt 6579 Sfmt 6579 E:\PUBLAW\PUBL023.116 PUBL023 dkrause on DSKBC28HB2PROD with PUBLAWS 133 STAT. 966 PUBLIC LAW 116–23—JUNE 25, 2019 Public Law 116–23 116th Congress An Act To amend title 38, United States Code, to clarify presumptions relating to the June 25, 2019 exposure of certain veterans who served in the vicinity of the Republic of Vietnam, [H.R. 299] and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Blue Water Navy the United States of America in Congress assembled, Vietnam Veterans Act SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. of 2019. 38 USC 101 note. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019’’. SEC. 2. CLARIFICATION OF PRESUMPTIONS OF EXPOSURE FOR VET- ERANS WHO SERVED IN VICINITY OF REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM. (a) IN GENERAL.—Chapter 11 of title 38, United States Code, is amended by inserting after section 1116 the following new section: 38 USC 1116A. ‘‘§ 1116A. Presumptions of service connection for veterans who served offshore of the Republic of Vietnam Time period. ‘‘(a) SERVICE CONNECTION.—For the purposes of section 1110 of this title, and subject to section 1113 of this title, a disease covered by section 1116 of this title becoming manifest as specified in that section in a veteran who, during active military, naval, or air service, served offshore of the Republic of Vietnam during the period beginning on January 9, 1962, and ending on May 7, 1975, shall be considered to have been incurred in or aggravated by such service, notwithstanding that there is no record of evidence of such disease during the period of such service. -

Davie Blue Route and Times

TOWN OF DAVIE REVISED BLUE ROUTE (WEST) 1 2 3 4 2 5 6 7 8 7 9 10 11 12 11 13 14 15 1 West West Regional Terminal Shenandoah 136th Ave & SR 84 Orange Park Sunshine Villiage Western Hills Shenandoah Paradise Village Kings of 84Manor/South Winn 84Dixie/Plaza Rexmere Villiage Winn 84Dixie/Plaza Publix Pine Island Plaza Nob Hill RD/SR 84 Indian Ridge Middle School Publix Pine Island Plaza Pine Ridge Condos Publix Pine Island Plaza City Mobile Park Home Estates Tower Shops/Best Buy Westfield Mall West Regional Terminal 8:00 AM 8:13 AM 8:15 AM 8:18 AM 8:28 AM 8:34 AM 8:38 AM 8:45 AM 8:52 AM 8:55 AM 8:58 AM 9:06 AM 9:10 AM 9:15 AM 9:23 AM 9:30 AM 8:45 AM 8:57 AM 9:00 AM 9:09 AM 9:14 AM 9:19 AM 9:27 AM 9:30 AM 9:37 AM 9:40 AM 9:48 AM 9:51 AM 9:55 AM 10:00 AM 10:08 AM 10:15 AM 9:30 AM 9:43 AM 9:45 AM 9:48 AM 9:58 AM 10:04 AM 10:08 AM 10:15 AM 10:22 AM 10:25 AM 10:28 AM 10:36 AM 10:40 AM 10:45 AM 10:53 AM 11:00 AM 10:15 AM 10:27 AM 10:30 AM 10:39 AM 10:44 AM 10:49 AM 10:57 AM 11:00 AM 11:07 AM 11:10 AM 11:18 AM 11:21 AM 11:25 AM 11:30 AM 11:38 AM 11:45 AM 11:00 AM 11:13 AM 11:15 AM 11:18 AM 11:28 AM 11:34 AM 11:38 AM 11:45 AM 11:52 AM 11:55 AM 11:58 AM 12:06 PM 12:10 PM 12:15 PM 12:23 PM 12:30 PM 12:45 PM 12:58 PM 1:00 PM 1:03 PM 1:13 PM 1:19 PM 1:23 PM 1:30 PM 1:37 PM 1:40 PM 1:43 PM 1:51 PM 1:55 PM 2:00 PM 2:08 PM 2:15 PM 1:30 PM 1:42 PM 1:45 PM 1:54 PM 1:59 PM 2:04 PM 2:12 PM 2:15 PM 2:22 PM 2:25 PM 2:33 PM 2:36 PM 2:40 PM 2:45 PM 2:53 PM 3:00 PM 2:15 PM 2:28 PM 2:30 PM 2:33 PM 2:43 PM 2:49 PM 2:53 PM 3:00 PM 3:07 PM 3:10 PM 3:13 PM 3:21 PM 3:25 PM 3:30 PM 3:38 PM 3:45 PM 3:00 PM 3:12 PM 3:15 PM 3:24 PM 3:29 PM 3:34 PM 3:42 PM 3:45 PM 3:52 PM 3:55 PM 4:03 PM 4:05 PM 4:10 PM 4:15 PM 4:23 PM 4:30 PM 3:45 PM 3:58 PM 4:00 PM 4:03 PM 4:13 PM 4:19 PM 4:23 PM 4:30 PM 4:37 PM 4:40 PM 4:43 PM 4:51 PM 4:55 PM 5:00 PM 5:08 PM 5:15 PM Ride The Town of Davie Blue Route (West) Davie Community Bus BCT Route WEST REGIONAL 2 Dr. -

Shades of Blue

Episode # 101 Script # 101 SHADES OF BLUE “Pilot” Written by Adi Hasak Directed by Barry Levinson First Network Draft January 20th, 2015 © 20____ Universal Television LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NOT TO BE DUPLICATED WITHOUT PERMISSION. This material is the property of Universal Television LLC and is intended solely for use by its personnel. The sale, copying, reproduction or exploitation of this material, in any form is prohibited. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is also prohibited. PRG-17UT 1 of 1 1-14-15 TEASER FADE IN: INT. MORTUARY PREP ROOM - DAY CLOSE ON the Latino face of RAUL (44), both mortician and local gang leader, as he speaks to someone offscreen: RAUL Our choices define us. It's that simple. A hint of a tattoo pokes out from Raul's collar. His latex- gloved hand holding a needle cycles through frame. RAUL Her parents chose to name her Lucia, the light. At seven, Lucia used to climb out on her fire escape to look at the stars. By ten, Lucia could name every constellation in the Northern Hemisphere. (then) Yesterday, Lucia chose to shoot heroin. And here she lies today. Reveal that Raul is suturing the mouth of a dead YOUNG WOMAN lying supine on a funeral home prep table. As he works - RAUL Not surprising to find such a senseless loss at my doorstep. What is surprising is that Lucia picked up the hot dose from a freelancer in an area I vacated so you could protect parks and schools from the drug trade. I trusted your assurance that no one else would push into that territory. -

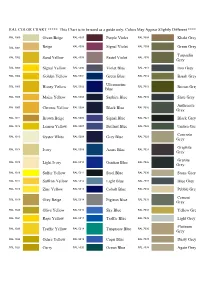

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Eastern Indigo Snake (Flier)

How To Distinguish Eastern Indigo Snakes Eastern indigo snakes became federally protected as threatened under the Endangered Species Act From Other Common Species in 1978, and they are also protected as threatened by Florida and Georgia. It is illegal to harass, harm, capture, keep, or kill an eastern indigo snake without specific state and/or federal permits. Life History Eastern indigo snakes use a wide variety of habitats The historic range of the eastern ranging from very wet to very dry. They tend to stay indigo snake (shown in dark green) in a specific area known as a home range, but this extended from the southern-most tip Adult eastern indigo snakes may be area is not static and can change over time, of South Carolina west through southern confused with few other species, due Georgia, Alabama, and into eastern to the indigo’s glossy blue-black probably in response to habitat conditions and Mississippi. The current range is shown in color and large size (5–7 ft.). prey availability. Because indigo snakes are sizeable light green. The eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon predators that actively hunt for their food, they couperi) has the distinction of being the need large home ranges. Males have been shown longest snake native to the United States. to use between 50 and 800 acres, whereas females often used for shelter. The snake may share the Eastern indigos typically range from 5 to 7 occupy up to 370 acres. During the winter, home burrow with a tortoise, but most often indigos will feet long, but can reach lengths greater than range sizes are smaller, particularly in the cooler occupy an old burrow that a tortoise has deserted. -

DWDM “Color” Bands for CATV Industry

Notes/Answer Question Scenario Summary Keywords © 2003Fiberdyne Labs,Inc. the DWDMchannels(andwavelengths)aredividedamongthesethree,CATV,colorbands. channels aregroupedintothree“color”bands:Blue,PurpleandRed.Thefollowingtableshowshow industry typicallyusesonlychannels19through59.WithintheCableTVindustry,theseC-Band According totheITU'sDWDMGrid,C-Bandincludeschannels1through72.However,CATV optic applications,likeCableTelevision(CATV). Bands areconvenientwaysfordescribingagroupofwavelengths,whichusedinvariousfiber- defined bytheInternationalTelecommunicationUnion(ITU)“Grid,”as1520.25-nmto1577.03-nm. Band) iscenteredat1550-nm.TheC-band,forDenseWavelengthDivisionMultiplexing(DWDM), Fiber-optic wavelengthsaredividedintoseveral“bands.”Forexample,theC-Band(orConventional- Which DWDMchannelsarerepresentedbywhichcolor“band?” Purple andRed. A CableTVproviderasksforDWDMmodule.Thechannelsarespecifiedusingthecolors:Blue, Red channels.Thenarrowsection,whichdividestheandBlue,includesPurple Red. Basically,thelowerhalf,ofC-Band,includesbluechannels.Theupperhalf For fiber-optic,Cable-TVpurposes,the“C-band”isdividedintothreecolor“bands:”Blue,Purpleand Application, CATV,DWDM,Fiber-optics that onebanddoesnotoverlap anotherband. Purple bandisusedasa“guard band.”Aguardbandisarelativelylargeseparation, whichensures channels, intotheaboveRed andBluegroups.Insomeapplications,liketheRed/Blue filter,the Note Or, graphically.... C h # : someofFiberdyne'sDWDM productsusea“Red/Blue”filter.Thisfilterdivides theITUGrid : 59 Channel Numbers 58 57 59 to45 56 35 to19 43 to37 55 54 B 53 L DWDM “Color”BandsforCATVIndustry 52 U 51 E 50 49 48 47 Application Note Wavelengths (nm) 1530.33 to1541.35 46 1549.32 to1562.23 1542.94 to1547.72 www.fiberdyne.com 45 43 P 42 U 41 R 40 P 39 L 38 E 37 35 34 33 CATV ColorBand 32 AN3023 Rev B, Page 31 30 Purple Blue Red 29 R 28 E 27 D 26 25 24 23 22 1 21 of 20 1 19. -

BLUE ROUTE Regular

FARES Notifying the Public of Rights Under Title VI VISTA TRANSIT The City of Sierra Vista/Vista Transit operates its programs and services without regard to race, color, national origin, or disability in accordance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, REGULAR FARE INFORMATION and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA). Any person who believes she or he has been aggrieved by any BLUE ROUTE Regular............................................................$1.25 unlawful discriminatory practice under Title VI may file a complaint with the City of Sierra Vista/Vista Transit. One-Day Pass ..............................................$3.00 For more information on the City of Sierra Vista/Vista Transit’s civil rights program, and the procedures to file Day passes may be purchased in advance. a complaint, contact the Transit Administrator (520) 417-4888; or visit the Transit Center at 2050 E. Wilcox Day passes are not available on the bus and must Avenue, Sierra Vista, AZ 85635. For more information, visit be purchased at the transit center. VistaTransit.org. A separate complaint may be filed with the Federal Transit DISCOUNTED FARE INFORMATION Administration (FTA) by filing a complaint directly with the corresponding offices of Civil Rights: FTA: ATTN: Complaint Passenger must display valid discount card. Team, East Building, 5th Floor-TCR 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE, Washington, DC 20590. Senior Citizen (aged 65 and older) ......$.60 Aviso al Público Sobre los Derechos Bajo el Título VI Disabled Citizen ...........................................$.60 City of Sierra Vista/Vista Transit asegura complir con el Título Children (5 & under) ............................... -

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Flags and Symbols � � � Gilbert Baker Designed the Rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’S Gay Freedom Celebration

Flags and Symbols ! ! ! Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Celebration. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony and violet for the soul.! " Rainbow Flag First unveiled on 12/5/98 the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top (representing same-gender attraction,) a broad stripe in blue at the bottoms (representing opposite- gender attractions), and a narrower deep lavender " band occupying the central fifth (which represents Bisexual Flag attraction toward both genders). The pansexual pride flag holds the colors pink, yellow and blue. The pink band symbolizes women, the blue men, and the yellow those of a non-binary gender, such as a gender bigender or gender fluid Pansexual Flag In August, 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen following a vote. The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe the grey-are between sexual and asexual, the white " stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community. Asexual Flag The Transgender Pride flag was designed by Monica Helms. It was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000. The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes. Two light blue which is the traditional color for baby boys, two pink " for girls, with a white stripe in the center for those Transgender Flag who are transitioning, who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender, and those who are intersex. -

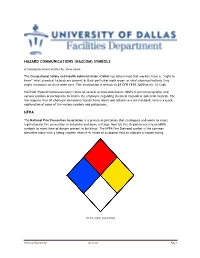

Hazard Communications (Hazcom) Symbols Nfpa

HAZARD COMMUNICATIONS (HAZCOM) SYMBOLS A training document written by: Steve Serna The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has determined that workers have a, “right to know” what chemical hazards are present in their particular work areas, or what chemical hazards they might encounter on their work sites. This information is written in 29 CFR 1910.1200 of the US Code. HAZCOM (Hazard Communications) relies on several written documents (MSDS & written programs) and various symbols or pictograms to inform the employee regarding chemical hazards or potential hazards. The law requires that all chemical containers/vessels have labels and adhere to a set standard; here is a quick explanation of some of the various symbols and pictograms… NFPA The National Fire Prevention Association is a private organization that catalogues and works to enact legislation for fire prevention in industrial and home settings. Most US Fire Departments rely on NFPA symbols to warn them of danger present in buildings. The NFPA Fire Diamond symbol is the common identifier along with a rating number (from 0-4) inside of a colored field to indicate a hazard rating. NFPA FIRE DIAMOND Hazcommadesimple.doc Opr: Serna Page 1 HAZARD RATINGS GUIDE For example: Diesel Fuel has an NFPA hazard rating of 0-2-0. 0 for Health (blue), 2 for Flammability (red), and 0 for Instability/Reactivity (yellow). HMIS (taken from WIKIPEDIA) The Hazardous Materials Identification System (HMIS) is a numerical hazard rating that incorporates the use of labels with color-coded bars as well as training materials. It was developed by the American Paints & Coatings Association as a compliance aid for the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard. -

Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act 2019 Law Extends Benefits for Eligible Veterans

Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act 2019 Law Extends Benefits for Eligible Veterans Public Law 116-23, (Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act 2019) Public Law 116-23, (Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act 2019) was signed into law on June 25, 2019 and takes effect January 1, 2020. The law extends a presumption of herbicide exposure to Blue Water Navy Veterans who served in the Republic of Vietnam and the offshore waters. Blue Water Navy Survivors, and certain dependents may be entitled to benefits if the Veteran was exposed. Under the law, certain Veterans, who served in the offshore waters of the Republic of Vietnam and Cambodia, or who had service in the Korean Demilitarized zone (DMZ), may be entitled to disability compensation for conditions that are related to herbicide exposure. The law also provides benefits for children born with spina bifida whose parent was a Veteran with verified herbicide exposure in Thailand. To be entitled to VA benefits, these Veterans must have served between January 9, 1962, and May 7, 1975, and have one or more of the conditions that are listed in section 3.309(e) of title 38, Code of Federal Regulations. Conditions related to presumed How do I file a claim for disability herbicide exposure1: compensation or survivor benefits? » Amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis » Apply using the guidance at www.va.gov, www.va.gov/ disability/dependency-indemnity-compensation OR » Chloracne, or other acneform disease consistent with chloracne » For initial compensation claims, submit a VA Form 21-526EZ; For initial DIC claims, submit a VA Form 21P-534EZ; » Chronic B-cell leukemias For previously denied claims, submit a VA Form 20-0995 OR » Diabetes mellitus, Type 2 » VA-accredited Veterans Service Organization representative, attorney, or claims agent OR » Ischemic heart disease » Go to a VA regional office and have a VA employee assist you. -

R Color Cheatsheet

R Color Palettes R color cheatsheet This is for all of you who don’t know anything Finding a good color scheme for presenting data about color theory, and don’t care but want can be challenging. This color cheatsheet will help! some nice colors on your map or figure….NOW! R uses hexadecimal to represent colors TIP: When it comes to selecting a color palette, Hexadecimal is a base-16 number system used to describe DO NOT try to handpick individual colors! You will color. Red, green, and blue are each represented by two characters (#rrggbb). Each character has 16 possible waste a lot of time and the result will probably not symbols: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F: be all that great. R has some good packages for color palettes. Here are some of the options “00” can be interpreted as 0.0 and “FF” as 1.0 Packages: grDevices and i.e., red= #FF0000 , black=#000000, white = #FFFFFF grDevices colorRamps palettes Two additional characters (with the same scale) can be grDevices comes with the base cm.colors added to the end to describe transparency (#rrggbbaa) installation and colorRamps topo.colors terrain.colors R has 657 built in color names Example: must be installed. Each palette’s heat.colors To see a list of names: function has an argument for rainbow colors() peachpuff4 the number of colors and see P. 4 for These colors are displayed on P. 3. transparency (alpha): options R translates various color models to hex, e.g.: heat.colors(4, alpha=1) • RGB (red, green, blue): The default intensity scale in R > #FF0000FF" "#FF8000FF" "#FFFF00FF" "#FFFF80FF“ ranges from 0-1; but another commonly used scale is 0- 255.