Work Release Participation Fees and the Takings Clause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

PM 8010.1B Work Release Program

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA EFFECTIVE January 18, 2018 Page 1 of 42 DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS DATE: SUPERSEDES: 8010.1A April 4, 2012 OPI: Community Corrections PROGRAM MANUAL REVIEW DATE: January 18, 2019 Approving Quincy L. Booth Authority Director SUBJECT: WORK RELEASE PROGRAM NUMBER: 8010.1B Attachments: Attachment A Agreement for Work Release Participation Attachment B Employer Agreement for Work Release Attachment C Request for Halfway House Placement Attachment D Halfway House Referral Package Checklist Attachment E Halfway House General Rules and Orientation Attachment F Inter-Institutional Transfer Attachment G Resident Employment Verification Attachment H Monthly Performance Report Card Attachment I DEMS Escape Report Attachment J DOC Form 1 Report of Significant Incident/Extraordinary Occurrence Attachment K Emergency Notification Attachment L Apprehension Report Attachment M Judge Affidavit/ Violation Report SUMMARY OF CHANGES: Section Change Changes Major revisions to the policy. APPROVED: _________________________ _____1/18/2018_______ Quincy L. Booth, Director Date Signed DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA EFFECTIVE DATE: January 18, 2018 Page 2 of 42 DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS SUPERSEDES: 8010.1A PROGRAM MANUAL April 4, 2012 REVIEW DATE: January 18, 2019 SUBJECT: WORK RELEASE PROGRAM NUMBER: 8010.1B Attachments: Attachments A-M 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE. To establish policy and procedures for: a. Placing sentenced misdemeanant inmates and court ordered pretrial defendants into contract Community Correctional Centers (CCC) referred to as Halfway Houses, Halfway and work release from a DOC jail facility; b. Action upon program failure, or upon other court-ordered disposition Releasing inmates and pretrial defendants upon expiration of their sentence, ; and c. Providing overall contract administration of the program. 2. POLICY. -

The American Gulag: the Correctional Industrial Complex in America

, j The American Gulag: The Correctional Industrial Complex in America Randall G. Shelden Department of Criminal Justice University of Nevada-Las Vegas Introduction "More than 200,000 scientists and engineers have applied themselves to solving military problems and hundreds of thousands more to innovation in other areas of modern life, but only a handful are working to control the crimes that injure or frighten millions of Americans each year. Yet the two communities have much to offer each other: Science and technology is a valuable source of knowledge and techniques for combating crime; the criminal justice system represents a vast area of challenging problems. ,,1 President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, 1967. A specter is haunting America and it is not the specter of "communism" that Marx and Engels warned us about over 100 years ago. This is much more threatening. This is the specter of the "criminal justice industrial complex." It is an industry run amok. It is awash with cash and profits beyond anyone's imagination. It needs crime. It needs victims. It needs the blood of citizens, like a vampire does. As the news industry saying goes, "If it bleeds, it leads. " Crime today, as always, is often front page news. It dominates the local nightly newscasts, complete with film footage of the victims and the perpetrators. Prime time television is often similarly dominated by crime - from full-length movies to so-called "live" broadcasts of police in action catching criminals. Millions flock to the movie theaters every week to see the latest episodes of crime and violence. -

Butch Baker Sheriff of Henry County

Contents HENRY COUNTY JAIL Section A Henry County Jail Manual Page 2 Property Accepted Page 3 Visitation Schedule Page 3 Recreation Page 4 Telephone Call Policy Page 4 Laundry Schedule Page 4 HENRY COUNTY SHERIFF’S DEPARTMENT Personal Property Page 5 HENRY COUNTY JAIL ANNEX Section B Henry County Jail Annex Manual Page 8 Community Service Guidelines Page 11 Henry County Jail Henry County Jail Annex Guidelines Page 12 Work Release Status Information Page 12 Community Service & Work Release Eligibility Page 14 & Work Release Recommendation Page 14 Class & Education Violations/Sanctions Page 14 Henry County Jail Annex Drug Violations/Sanctions Page 14 Work Release Phase Programs Page 14 Visitation Schedule Page 15 Court Ordered Substance Counseling Page 15 Child Support/Body Attachment Inmates on Work Release Status Page 15 Money Withdraw off Commissary Account Page 15 Property Accepted for Inmates Page 16 Personal Property Permitted Page 16 NA/AA Meetings Page 17 Locker Assignment Page 17 Recreation Schedule Page 17 Job Search Page 17 HENRY COUNTY JAIL & HENRY COUNTY JAIL ANNEX SECTION C Escape from Custody Agreement Page 19 Major & Minor Offenses Page 20 Inmate Disciplinary Due Process Page 22 Behavior Page 23 Care of the Jail & Henry County Jail Annex Page 23 Headcount Procedure Page 23 Medical Grievance Page 23 Medical Services Page 23 Cellblock Operations Page 23 Contraband & Prohibited Property Page 24 Meals Page 24 Personal Hygiene Page 24 Commissary & Commissary Account Page 25 GED Classes & GED Credit Time Page 25 Inmate Grievance -

Gang Diversion Program Implementation

Running head: Gang Diversion Program Implementation Gang Diversion Program Implementation: A Reentry Program for Inmates with STG Affiliations at a Supermax Prison by Elizabeth Zoccole Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters Applied Sciences in the Criminal Justice Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 Gang Diversion Program Implementation Gang Diversion Program Implementation: A Directed Study of STG Affiliations at Ohio State Penitentiary Elizabeth Zoccole I hereby release this Gang Diversion Program Implementation: A Directed Study of STG Affiliations at Ohio State Penitentiary to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ____________________________________________ _________ Elizabeth Zoccole, Student Date Approvals: ____________________________________________ _________ Dr. Richard Rogers, Thesis Advisor Date _____________________________________________ _________ Dr. Christopher Bellas Committee Member Date _____________________________________________ _________ Professor Phillip Dyer, Committee Member Date _____________________________________________ ________ Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date Gang Diversion Program Implementation ABSTRACT My interest in rehabilitation started during my undergraduate internship with the Adult Parole Authority in Youngstown, Ohio. During my time there I noticed the lack of diverse programming for offenders. There were wide ranges of programs for drugs, or mental health but there were none for gang members wanting to leave the gang. The research I completed is relevant due to the underlying fact that this population lacks the programs and assistance needed to escape and overcome the gang lifestyle. -

Handbook for Family and Friends of Inmates

Handbook for Family and Friends of Inmates NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY PRISONS 2017 Helpful Information to Remember ♦ For general information, you can call the prison where your relative or friend is housed. ♦ For specifi c information about a certain inmate, contact the inmate’s case manager at the prison. ♦ The prison chaplain or designated religious services staff can help you. ♦ Always ask about and follow the prison rules where your relative or friend is housed. ♦ You can fi nd more information on the N.C. Depart- ment of Public Safety’s website at www.ncdps.gov. ♦ If you still need help, call 1-800-368-1985 or 919- 838-4000. Handbook for Family and Friends Introduction Every offender is a part of a family. Incarceration is often a dif- fi cult time not only for the offenders, but also for their family and friends. It can be overwhelming for family and friends in the separation and in understanding the rules and regulations that govern prisons operated by the State of North Carolina through the Department of Public Safety (DPS). This handbook may not answer all of your questions, but we hope the general information it contains about the North Carolina prison system will help you during this diffi cult time. Please take the time to read this handbook, and remember that it is for informational purposes only. Rules and regulations outlined in this book are subject to change and standard operation proce- dures can vary among prison facilities. DPS policies and proce- dures are reviewed and updated from time to time, as are state laws that affect prison operations. -

The Use and Impact of Correctional Programming for Inmates on Pre- and Post-Release Outcomes

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice National Institute of Justice The Use and Impact of Correctional Programming for Inmates on Pre- and Post-Release Outcomes June 2017 Grant Duwe, Ph.D. Minnesota Department of Corrections This paper was prepared with support from the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, under contract number 2010F_10097 (CSR, Incorporated). The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Justice. NCJ 250476 U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh St. N.W. Washington, DC 20531 Howard Spivak Acting Director, National Institute of Justice This and other publications and products of the National Institute of Justice can be found at: National Institute of Justice Strengthen Science • Advance Justice http://www.NIJ.gov Office of Justice Programs Building Solutions • Supporting Communities • Advancing Justice http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov The National Institute of Justice is the research, development, and evaluation agency of the U.S. Department of Justice. NIJ’s mission is to advance scientific research, development, and evaluation to enhance the administration of justice and public safety. The National Institute of Justice is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance; the Bureau of Justice Statistics; the Office for Victims of Crime; the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. National Institute of Justice | NIJ.gov The Use and Impact of Correctional Programming for Inmates on Pre- and Post-Release Outcomes Introduction State and federal prisons have long provided programming to inmates during their confinement. -

Work Release in the United States Stanley E

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 54 Article 2 Issue 3 September Fall 1963 Work Release in the United States Stanley E. Grupp Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Stanley E. Grupp, Work Release in the United States, 54 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 267 (1963) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. WORK RELEASE IN THE UNITED STATES STANLEY E. GRUPP The author is Assistant Professor of Sociology in the Department of Social Sciences of the Illinois State Normal University. He received the M.A. degree from the University of Iowa. Professor Grupp's publications include articles in the fields of anthropology, penology, and criminology. What are the objectives of a work release program? What are the comparative merits of the various types of work release legislation? What are the major difficulties encountered in implementation of work release? And how does work release measure up to society's requirements for effective penal sanctions? In the following article, Professor Grupp considers these and other questions growing out of the increasing use of work release in United States penological practice.-EDIrO. In United States penological practice, the Idaho (1957), 7 North Carolina (1957), 8 Minnesota 0 "work release"' program is well underway. -

Chapter 1.28 STANDARDS for CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES

Chapter 1.28 STANDARDS FOR CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES Sections: 1.28.010 General. 1.28.020 Definitions. 1.28.030 Physical plant standards. 1.28.040 General administration. 1.28.050 Staff positions. 1.28.060 Training. 1.28.070 Records. 1.28.080 Emergency procedures. 1.28.090 Fire prevention – Suppression. 1.28.100 Overcrowding. 1.28.110 Use of force. 1.28.120 Admissions. 1.28.130 Preclassification. 1.28.140 Orientation. 1.28.150 Classification – Segregation. 1.28.160 Good time. 1.28.170 Release and transfer. 1.28.180 Transportation. 1.28.190 Staffing. 1.28.200 Supervision – Surveillance. 1.28.210 Critical articles. 1.28.220 Prisoner rights. 1.28.230 Discipline. 1.28.240 Grievance procedure. 1.28.250 Responsible physician and licensed staff. 1.28.260 Health care policy and procedures. 1.28.270 Health screening. 1.28.280 Access to health care. 1.28.290 Health care training. 1.28.300 Medications control. 1.28.310 Health care records. 1.28.320 Special medical issues. 1.28.330 Access to facilities. 1.28.340 Food. 1.28.350 Clothing – Bedding – Personal items. 1.28.360 Sanitation. 1.28.370 Services. 1.28.380 Programs. 1.28.390 Telephone usage. 1.28.400 Mail. 1.28.410 Visitation. 1.28.420 Severability. 1.28.010 General. A. The rules set forth in this chapter shall apply to correctional facilities generally within Whatcom County, but shall not apply to holding facilities, detention facilities, work release facilities or juvenile facilities unless they are specifically mentioned in the provisions set forth in this chapter. -

Inmate Handbook

Arkansas Department of Correction Inmate Handbook 1st Printing, December 1971 (Revised) 2nd Printing, July 1972 (Revised) 3rd Printing, November 1972 (Revised) 4th Printing, January 1975 (Revised) 5th Printing, July 1978 (Revised) 6th Printing, May 1981 (Revised) 7th Printing, August 1981 (Revised) 8th Printing, October 1983 (Revised and Recalled) 9th Printing, September 1986 (Revised) 10th Printing, February 1991 (Revised) 11th Printing, February 1994 (Revised) 12th Printing, December 2001 (Revised) 13th Printing, May 2006 (Revised) 14th Printing, January 2007 (Revised) 15th October 2010 (Revised) 16th October 2011 (Revised) 17th Printing February 2012 (Revised) 18th Printing January 2013 (Revised) Printed by Arkansas Correctional Industries 1 Table of Contents Diagnostic Process 3 Statutory Responsibilities 4 Initial Assignments 4 Transfers 4 Classification 5 Following Orders 7 Living in a Prison Setting 7 Cleanliness 8 Grooming Policy 8 Security Issues 9 Prison Rape Elimination Act 10 Tobacco Regulations 11 Grievances 11 Food Service 12 Telephone Use 13 Personal Clothing/Property 13 Major Disciplinary Process 14 Major Disciplinary Appeal 16 Minor Disciplinary Process 18 Behavior Rules/Regulations 18 Punitive Segregation 23 Administrative Segregation 24 Protective Custody 24 Detainers 24 Interstate Compact 24 Medical Services 25 Program Services 25 Education 27 Work Release 27 Pre Release 28 Religious Services 28 Mail Policy 29 Visitation 30 Furloughs 32 Commissary 32 Money 33 Marriage 34 Law Library 34 Inmate Groups 34 Parole/Pardons 35 Executive Clemency 36 Emergency Powers 36 Legal Assistance 36 Introduction The Arkansas Department of Correction is not responsible for you being here. You engaged in some behavior for which a sentence to the Arkansas Department of Correction is the price you pay. -

Glenn County Sheriff's Office

GLENN COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE CORRECTIONS DIVISION JAIL INFORMATION HANDBOOK Lt. Bouldin JAIL COMMANDER REVISED March 2017 ***YOU WILL BE REQUIRED TO RETURN THIS HANDBOOK*** TO CORRECTIONAL STAFF UPON YOUR RELEASE FROM THIS DETENTION FACILITY GLENN COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE INMATE ORIENTATION MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION PAGE 4 II. GENERAL INFORMATION PAGE 4 A. NO HOSTAGE POLICY PAGE 4 B. NO SMOKING POLICY PAGE 4 C. ADRESSING STAFF PAGE 4 D. INMATE CLASSIFICATION PAGE 4 E. IDENTIFICATION WRISTBANDS PAGE 4 F. ADMISSION KITS PAGE 5 G. PERSONAL PROPERTY PAGE 5 H. ACCEPTANCE OF MONEY PAGE 5 I. RELEASE OF PROPERTY AND MONEY PAGE 5 J. INMATE WEDDINGS PAGE 6 K. INMATE REQUEST FORMS PAGE 6 L. INMATE SICK CALL FORMS PAGE 6 M. INMATE GRIEVANCES PAGE 6 N. FIRE PREVENTION & SAFETY MEASURES PAGE 7 O. PRISON RAPE ELIMINATION ACT (PREA) PAGE 7 III. HOUSING UNIT ACTIVITIES PAGE 7 A. HEADCOUNT PAGE 7 B. LOCKDOWNS PAGE 8 C. MOVEMENT PAGE 8 D. SANITATION PAGE 9 E. CLOTHING ISSUE PAGE 9 F. CLOTHING EXCHANGE PAGE 10 G. GROOMING AND PERSONAL APPEARANCE PAGE 10 H. MEALS PAGE 10 I. DAY ROOMS PAGE 11 J. EXERCISE AREA PAGE 12 K. COMMISSARY PAGE 12 L. VISITATION PAGE 12 2 IV. CONTRABAND PAGE 13 V. COURT INFORMATION PAGE 14 A. COURTS PAGE 14 B. COURT APPEARANCES PAGE 14 VI. CORRESPONDENCE PAGE 14 A. LEGAL MAIL PAGE 14 B. PERSONAL MAIL PAGE 15 VII. SERVICES PAGE 16 A. HEALTH SERVICES PAGE 16 B. FEMALE INMATE HEALTH SERVICES PAGE 17 C. MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES PAGE 17 D. -

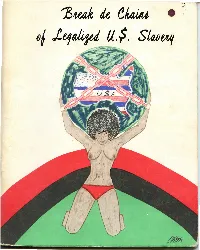

510.Prisonwomen.Breakdechains

- Copyright 0 1976 by the North Carolina Women's Prison Book Project First printing, November, 1976 1,000 copies The members of Second printing, April, 1977 on this book becaus 1,200 copies Women's Prison. A Feminists members a Prison Project made part of the work in fundraising, layout and distribution, at the North Caroli for the liberation . This material has been copyrighted to prevent use by Greetings my Sistas profiteers. If you want to use anything from the book, just I extend total write and let us know what you're using it for. and dedication. Originally, We Photographs provided by Big Mama Rag, Frank Cuthbertson, as We just wanted t and The News and Observer. the book developed, attempt to briefly We encourage people to write to the sistas at: 1034 the sistas. Bragg St., Raleigh, N.C. 27610. Last January, printing a book con Copies of this book are available at $2.00 each from: done since June of P.O. Box 27, Durham, N.C. 27702. Make checks payable to: monstrated to be tr< North Carolina Women's Prison Book. Please add 25<f per book for postage and handling. The members of Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists decided to work on this book because of our continuing interest in the struggle at. Women's Prison. A coalition between a group of Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists members and several members of the North Carolina Hard Times Prison Project made it possible for the book to be published. Our part of the work included collection and arrangement of articles, fundraising, layout, typing, paste-up, printing, collation, binding and distribution.