UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Silence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

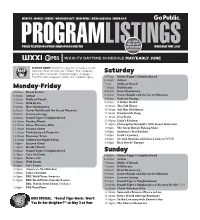

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

The Magic Christian on Talking Pictures TV Directed by Joseph Mcgrath in 1969

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 6th April 2020 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 The Magic Christian on Talking Pictures TV Directed by Joseph McGrath in 1969. Stars: Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr, with appearances by Raquel Welch, John Cleese, Graham Chapman, Spike Milligan, Christopher Lee, Richard Attenborough and Roman Polanski. Sir Guy Grand is the richest man in the world, and when he stumbles across a young orphan in the park he decides to adopt him and travel around the world spending cash. It’s not long before the two of them discover on their happy-go-lucky madcap escapades that money does, in fact, buy anything you want. Airs on Saturday 11th April at 9pm Monday 6th April 08:55am Wednesday 8th April 3:45pm Thunder Rock (1942) Heart of a Child (1958) Supernatural drama directed by Roy Drama, directed by Clive Donner. Boulting. Stars: Michael Redgrave, Stars: Jean Anderson, Barbara Mullen and James Mason. Donald Pleasence, Richard Williams. One of the Boulting Brothers’ finest, A young boy is forced to sell the a writer disillusioned by the threat of family dog to pay for food. Will his fascism becomes a lighthouse keeper. canine friend find him when he is trapped in a snowstorm? Monday 6th April 10pm The Family Way (1966) Wednesday 8th April 6:20pm Drama. Directors: Rebecca (1940) Roy and John Boulting. Mystery, directed by Alfred Hitchcock Stars: Hayley Mills, Hywel Bennett and starring Laurence Olivier, John Mills and Marjorie Rhodes. Joan Fontaine and George Sanders. -

Transgender Representation on American Narrative Television from 2004-2014

TRANSJACKING TELEVISION: TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION ON AMERICAN NARRATIVE TELEVISION FROM 2004-2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Kelly K. Ryan May 2021 Examining Committee Members: Jan Fernback, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Ron Becker, External Member, Miami University ABSTRACT This study considers the case of representation of transgender people and issues on American fictional television from 2004 to 2014, a period which represents a steady surge in transgender television characters relative to what came before, and prefigures a more recent burgeoning of transgender characters since 2014. The study thus positions the period of analysis as an historical period in the changing representation of transgender characters. A discourse analysis is employed that not only assesses the way that transgender characters have been represented, but contextualizes American fictional television depictions of transgender people within the broader sociopolitical landscape in which those depictions have emerged and which they likely inform. Television representations and the social milieu in which they are situated are considered as parallel, mutually informing discourses, including the ways in which those representations have been engaged discursively through reviews, news coverage and, in some cases, blogs. ii To Desmond, Oonagh and Eamonn For everything. And to my mother, Elaine Keisling, Who would have read the whole thing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the research and writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance, and therefore offer many thanks. To my Dissertation Chair, Jan Fernback, whose feedback on my writing and continued support and encouragement were invaluable to the completion of this project. -

MOLLY of DENALI Episode Descriptions and Curriculum Episodes #101-139

MOLLY OF DENALI Episode Descriptions and Curriculum Episodes #101-139 NOTE: EPISODE NUMBERS ARE NOT IN BROADCAST ORDER EPISODE 101: Grandpa’s Drum Molly finds an old photo of Grandpa as a child and is shocked to see him singing and drumming—Grandpa never sings. When Grandpa tells her he lost his songs when he gave his drum away, Molly goes on a mission to find his drum and return his songs to him. Curriculum: IT Learning Goals: To compare texts and integrate information across multiple textual sources when reading or researching (this could, but need not, lead to writing or developing a presentation). Molly and Tooey look at landmarks in a photo taken in the past and compare them to how the landmarks look in the present. To use a variety of language, navigational, structural, and graphical text features (like a photograph) to help access (read, listen to, and/or view) or convey (write, speak, and/or present, including visually) meaning (which vary depending upon the type of informational text). Graphical Feature: Photograph. Molly and Tooey examine an old photograph to find clues that help them discover what town the photograph was taken in. Social Studies: Collect and examine photographs of the past and compare with similar, current images. Classify events as belonging to past or present. Molly compares an old photograph to new images of towns in Alaska to discover what town the photograph was taken in. Alaska Native Value: Honoring your elders. Knowing who you are — you are an extension of your family. Continuing the practice of Native traditions. -

Cognotes Midwinter Meeting & Exhibits JANUARY 10 January 8–12, 2016

COGNOTES MIDWINTER MEETING & EXHIBITS JANUARY 10 January 8–12, 2016 SUNDAY Edition BOSTON, MA USE THE TAG #ALAMW16 AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Senator Cory Booker to Speak at Today’s ALA President’s Program ising United States tion and compassion must Senator Cory guide our nation toward RBooker will join a brighter future. Booker ALA President Sari Feldman was mayor of Newark from as speaker at her President’s 2006 to 2013, and became Program. This program, in the first black senator from partnership with the ALA New Jersey in 2013. Task Force on Equity, Di- In response to the New versity, and Inclusion, will Jersey Library Association’s take place today from 3:30 statement expressing disap- – 5:30 p.m. pointment about his ap- Senator Cory Booker Sen. Cory Booker pearance on the President’s makes the case through his work, and in Program in light of the library cuts during his forthcoming book United, that connec- his time as mayor of Newark, Feldman said, Isaac Mizrahi, designer, fashion industry leader, documentary film co-creator “Building relationships with policy makers Senator Cory Booker and actor, and TV talk show host, takes questions from librarians during his and influencers, many of whom have not his- ALA President’s Program Auditorium Speaker Series presentation. torically been library advocates, is essential to Sunday, 3:30 – 5:30 p.m. BCEC Ballroom West Mizrahi Tells Personal Stories see page 12 With Trademark Style saac Mizrahi kicked off the Auditorium include, The Adventures of Sandee, The Super- Sunrise Celebration to Speaker Series on Saturday morning with model, a graphic novel, and a fashion advice Feature Mary Frances Berry an inside look at the process he’s using book, How to Have Style. -

Discover South America: Chile, Argentina & Uruguay 2020

TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE Discover South America: Chile, Argentina & Uruguay 2020 Grand Circle Travel ® Worldwide Discovery at an Extraordinary Value 1 Dear Traveler, Timeless cultures ... unforgettable landscapes ... legendary landmarks. We invite you to discover centuries-old traditions and cosmopolitan gems with Grand Circle Travel on one of our enriching vacations around the globe. No matter what your dream destination, Grand Circle offers an unrivaled combination of value and experience—all in the company of like-minded fellow American travelers and a local Program Director. Assigned to no more than 42 travelers, these experts are ready and eager to share their homeland and insights as only a local can. Whether it's recommending their favorite restaurant, connecting travelers with people and culture, or providing the best regional maps to enhance your leisure time, our Program Directors are here to take care of all the details and ensure that you have a fun and carefree travel experience. You'll also enjoy the best value in the travel industry. Each of our trips includes all accommodations, most meals, exclusive Discovery Series events, guided tours, and most gratuities, all at a value that no other company can match. Plus, solo travelers can enjoy FREE Single Supplements on all Grand Circle Tours and extensions for even more value. In addition to our wealth of included features, each itinerary is balanced with ample free time to ensure you're able to make your vacation truly your own. Plus, with Grand Circle, you have the freedom to personalize your trip. For example, you can customize your air experience, and start your trip early or stay longer with our optional pre- and post-trip extensions. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Have Gun, Will Travel: the Myth of the Frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall

Feature Have gun, will travel: The myth of the frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall Newspaper editor (bit player): ‘This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, we print the legend’. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (dir. John Ford, 1962). Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott): ‘You know what’s on the back of a poor man when he dies? The clothes of pride. And they are not a bit warmer to him dead than they were when he was alive. Is that all you want, Steve?’ Steve Judd (Joel McCrea): ‘All I want is to enter my house justified’. Ride the High Country [a.k.a. Guns in the Afternoon] (dir. Sam Peckinpah, 1962)> J. W. Grant (Ralph Bellamy): ‘You bastard!’ Henry ‘Rico’ Fardan (Lee Marvin): ‘Yes, sir. In my case an accident of birth. But you, you’re a self-made man.’ The Professionals (dir. Richard Brooks, 1966).1 he Western movies that from Taround 1910 until the 1960s made up at least a fifth of all the American film titles on general release signified Lee Marvin, Lee Van Cleef, John Wayne and Strother Martin on the set of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance escapist entertainment for British directed and produced by John Ford. audiences: an alluring vision of vast © Sunset Boulevard/Corbis open spaces, of cowboys on horseback outlined against an imposing landscape. For Americans themselves, the Western a schoolboy in the 1950s, the Western believed that the western frontier was signified their own turbulent frontier has an undeniable appeal, allowing the closing or had already closed – as the history west of the Mississippi in the cinemagoer to interrogate, from youth U. -

Spring 2020 Newsletter

THE Wadhams Free Library Spring 2020 NEWS We’re reaching out to our library community to share some resources that may be useful or enjoyable - - and as a way to exchange ideas and give each other something else to think about. We hope that you and your loved ones are safe and well. Please contact us if we can help answer questions or provide resources. Have something you’d like to share? Call or e-mail us. 518-962-8717 [email protected] we’re so sorry to miss our Spring Sourdough Waffle & Frittata Extravaganza we look forward to seeing you when we can Please support our local businesses! If you can’t visit them now, consider buying a gift certificate. virus resources - here’s a place to start - there are many more - and remember to watch out for scams https://www.coronavirus.gov https://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/home https://www.co.essex.ny.us/Health/ a few of the many reading and information resources available online: https://cefls.org Clinton Essex Franklin Library System’s home page Click on the USE YOUR LIBRARY tab, then click on EBOOKS AND MORE or RESEARCH AND LEARNING TOOLS or KIDS & TEENS There’s a lot there to explore! https://www.myon.com myON digital reading resources for kids are free during the current school closures. Click login at the top of the screen. School name: New York Reads - Username: read - Password: books https://www.gutenberg.org/ free downloadable books Do you need your library card number and PIN in order to access e-books and other digital resources? Ask us! We’re expecting a delivery of new books and we’re thinking about how we might be able to hand out books - - separately! - - safely! - - cleanly! We’ll let you know what we come up with. -

Michele Promaulayko

September 12, 2016 | Vol. 69 No. 35 Read more at: minonline.com Top Story: Clowns, Cosplay and Calves Drive July Video Growth Desktop loses ground, mobile levels off and moving images continue to dominate Is mobile losing its muscle? The MPA’s Magazine Media 360º Brand Audience Report for July show an acceleration of the migration towards both smaller screens and sight-sound-motion and away from the desktop. No surprises. In year-over-year comparisons, in aggregate the member magazine brands show basically flat growth (+1.2%) in print and digital editions and a marked decline (-12.5%) in desktop audience. Again, no surprises. What's a bit surprising is that the mobile migration itself saw a modest 19% expansion. Compare this to the July 2015 trends, for instance, when mobile audience had grown 58.3% over July 2014. In just a year’s time, the shift of focus to video has been dramatic. In July 2015 we saw an annual YoY growth of only 6.2% in video uniques for magazine brands. But in July of this year, it's 43.6%. In terms of raw audience tonnage at least, if not monetization, this suggests that investments in streaming media and intelligent distribution are paying off. Continued on page 4 A Homecoming of Sorts for Michele Promaulayko The former Cosmo editor returns as EIC (and editorial director of Seventeen) As anyone who doesn't live under a rock knows, Hearst announced this week that Michele Promaulayko would return to the company where she previously worked for nine years as Cosmo's executive editor. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

Table of Contents

August-September 2015 Edition 4 _____________________________________________________________________________________ We’re excited to share the positive work of tribal nations and communities, Native families and organizations, and the Administration that empowers our youth to thrive. In partnership with the My Brother’s Keeper, Generation Indigenous (“Gen-I”), and First Kids 1st Initiatives, please join our First Kids 1st community and share your stories and best practices that are creating a positive impact for Native youth. To highlight your stories in future newsletters, send your information to [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Youth Highlights II. Upcoming Opportunities & Announcements III. Call for Future Content *************************************************************************************************** 1 th Sault Ste. Marie Celebrates Youth Council’s 20 Anniversary On September 18 and 19, the Sault Ste. Marie Tribal Youth Council (TYC) 20-Year Anniversary Mini Conference & Celebration was held at the Kewadin Casino & Convention Center. It was a huge success with approximately 40 youth attending from across the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians service area. For the past 20 years, tribal youth grades 8-12 have taken on Childhood Obesity, Suicide and Bullying Prevention, Drug Abuse, and Domestic Violence in their communities. The Youth Council has produced PSAs, workshops, and presentations that have been done on local, tribal, state, and national levels and also hold the annual Bike the Sites event, a 47-mile bicycle ride to raise awareness on Childhood Obesity and its effects. TYC alumni provided testimony on their experiences with the youth council and how TYC has helped them in their walk in life. The celebration continued during the evening with approximately 100 community members expressing their support during the potluck feast and drum social held at the Sault Tribe’s Culture Building.