The Wa.Ii Shorau-Sho of Keichu and Its Position in Historical Usance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Old Documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu

NINJAL International Symposium 2018 Approaches to Endangered Languages in Japan and Northeast Asia, August 6-8 The study of old documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu: Promise and Challenges Tomomi Sato (Hokkaido U) & Anna Bugaeva (TUS/NINJAL) [email protected] [email protected]) Introduction: Ainu • AINU (isolate, North Japan, moribund) • Is the only non-Japonic lang. of Japan. • Major dialect groups : Hokkaido (moribund), Sakhalin (extinct since 1993), Kuril (extinct since the end of XIX). • Was also spoken in Tōhoku till mid XVIII. • Hokkaido Ainu dialects: Southwestern (well documented) Northeastern (less documented) • Is not used in daily conversation since the 1950s. • Ethnical Ainu: 100,000. 2 Fig. 2 Major language families in Northeast Asia (excluding Sinitic) Amuric Mongolic Tungusic Ainuic Koreanic Japonic • Ainu shares only few features with Northeast Asian languages. • Ainu is typologically “more like a morphologically reduced version of a North American language.” (Johanna Nichols p.c.). • This is due to the strongly head-marking character of Ainu (Bugaeva, to appear). Why is it important to study Ainu? • Ainu culture is widely regarded as a direct descendant of the Jōmon culture which was spread in the Japanese archipelago in the Prehistoric time from about 14,000 BC. • Ainu is the only surviving Jōmon language; there had been other Jōmon lgs too: about 300 lgs (Janhunen 2002), cf. 10 lgs (Whitman, p.c.) . • Ainu is likely to be much more typical of what languages were like in Northeast Asia several millennia ago than the picture we would get from Chinese, Japanese or Korean. • Focusing on Ainu can help us understand a period of northeast Asian history when political, cultural and linguistic units were very different to what they have been since the rise of the great historically-attested states of East Asia. -

On Translation a Short Introduction to the Japanese Language Will

On Translation A short introduction to the Japanese language will illustrate the kind of difficulties one encounters in translating Japanese into the European languages, and vice versa. Linguistically, Japanese is an isolated language. It has no relation to Chinese. It must have had some relation to Korean, another isolated language, but the two went into different directions thousands of years ago. Some linguists claim that the Japanese language, along with the Korean, belongs to the Ural-Altaic family, yet the claim remains hypothetical. The Japanese language features some characteristics that would seem most strange to those who are only familiar with the European languages. For example, a grammatical subject is unnecessary in Japanese to construct a grammatically complete sentence. “淋しい” (Sabishii) means (someone is) lonely. It is a complete sentence, but there is no subject. The sentence may mean ‘I’m lonely,’ ‘you are lonely,’ ‘he/she is lonely,’ ‘the rock is lonely,’ ‘all human beings are lonely,’ etc, depending on the context. It may furthermore refer to a vague sense of loneliness which needn’t be specified. It is true that in some European languages, such as Italian, a grammatically complete sentence is possible without a named subject. But the subject can always be determined by the inflection of the verb (and often also by the changes in the articles, adjectives and nouns): “Sono sola,” “Sei solo.” A Japanese sentence may be very long and still be without a subject. Tale of Genji , for instance, might contain a sequence of three long sentences without subjects, yet in each a different subject would be implied. -

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

Title Classical Japanese in Linguistic and Cross-Cultural Perspective Sub

Title Classical Japanese in linguistic and cross-cultural perspective Sub Title Author De Wolf, Charles Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication 2020 year Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 英語英米文学 (The Keio University Hiyoshi review of English studies). Vol.73, No.2020 (9. ) ,p.69- 87 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?ko ara_id=AN10030060-20200930-0069 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または 出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守して ご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Classical Japanese in Linguistic and Cross-Cultural Perspective1) Charles De Wolf In the preface to his famous A Dictionary of the English Language (1755), Samuel Johnson notes: “When we see men grow old and die at a certain time one after another, from century to century, we laugh at the elixir that promises to prolong life to a thousand years; and with equal justice may the lexicographer be derided, who being able to produce no example of a nation that has preserved their words and phrases from mutability, shall imagine that his dictionary can embalm his language, and secure it from corruption and decay, that it is in his power to change sublunary nature, or clear the world at once from folly, vanity, and affectation.” I cite this not only to show that, though no modern linguist, Johnson was quite aware that “mutability” applies to human language as well as all else that is “sublunary,” but also to note that, as learned as he was, Johnson knew far less about the history of the English language than anyone with curiosity and access to Wikipedia can learn, in a matter of minutes or at most hours. -

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

Introduction to Kanbun: W4019x (Fall 2004) Mondays and Wednesdays 11-12:15, Kress Room, Starr Library (Entrance on 200 Level)

1 Introduction to Kanbun: W4019x (Fall 2004) Mondays and Wednesdays 11-12:15, Kress Room, Starr Library (entrance on 200 Level) David Lurie (212-854-5034, [email protected]) Office Hours: Tuesdays 2-4, 500A Kent Hall This class is intended to build proficiency in reading the variety of classical Japanese written styles subsumed under the broad term kanbun []. More specifically, it aims to foster familiarity with kundoku [], a collection of techniques for reading and writing classical Japanese in texts largely or entirely composed of Chinese characters. Because it is impossible to achieve fluent reading ability using these techniques in a mere semester, this class is intended as an introduction. Students will gain familiarity with a toolbox of reading strategies as they are exposed to a variety of premodern written styles and genres, laying groundwork for more thorough competency in specific areas relevant to their research. This is not a class in Classical Chinese: those who desire facility with Chinese classical texts are urged to study Classical Chinese itself. (On the other hand, some prior familiarity with Classical Chinese will make much of this class easier). The pre-requisite for this class is Introduction to Classical Japanese (W4007); because our focus is the use of Classical Japanese as a tool to understand character-based texts, it is assumed that students will already have control of basic Classical Japanese grammar. Students with concerns about their competence should discuss them with me immediately. Goals of the course: 1) Acquire basic familiarity with kundoku techniques of reading, with a focus on the classes of special characters (unread characters, twice-read characters, negations, etc.) that form the bulk of traditional Japanese kanbun pedagogy. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

Changes to the Basic Resident Registration Law ~Foreign

Update 258 Changes to the Basic Resident Registration Law ~Foreign residents will be subject to the Basic Resident Registration Law~ Quotation from Portal Site on Policies for Foreign Residents by Cabinet Office, Government of Japan http://www8.cao.go.jp/teiju-portal/eng/policy/index.html (English) http://www8.cao.go.jp/teiju-portal/port/index.html (Português) http://www8.cao.go.jp/teiju-portal/espa/index.html (Español) Foreign residents will be listed on the Basic Resident Registration With the soaring number of foreign nationals entering and residing in Japan each year, the establishment of a legal system by which munici- The Basic Resident Registration Law which currently does not apply to palities can provide basic public services to both foreign and Japanese foreign nationals will be revised, making it applicable to foreign nationals. residents has become an urgent concern. Consequently, foreign residents will be listed on the Basic Resident Registration along with Japanese residents. The Basic Resident Registration is the compiled residence records arranged by household. In order to address such concern, the law for partial amendments to the Basic Resident Registration Law was enacted at the 171st session of Diet and promulgated on July 15, 2009. This will make the Basic Resident Registration Law applicable to foreign residents and help improve their More convenient for foreign residents convenience and streamline municipalities’ operations. This amendment will come into effect within three years after the promulgation date (exact date is to be determined by the Cabinet). ◦This revision enables municipalities to have a better grasp of the members of multinational households (family composed of Japanese and non- In addition, the bill to abolish the Alien Registration Act and revise Japanese individuals), compared with the current two-tier system that list *concerned immigration laws was passed and enacted at the 171st Diet Japanese members and non-Japanese members of the same family in two session. -

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Timelines and Maps Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books English Version © Keio University Timelines and Maps East Asian History at a Glance Books are part of the flow of history. But it is not only about Japanese history. Many books travel over the sea time to time for several reasons and a lot of knowledge and information comes and go with books. In this course, you’ll see books published in Japan as well as ones come from China and Korea. Let’s take a look at the history in East Asia. You do not have to remember the names of the historical period but please refer to this page for reference. Japanese History Overview This is a list of the main periods in Japanese history. This may be a useful reference as we proceed in the course. Period Name of Era Name of Era - mid-3rd c. CE Yayoi 弥生 mid-3rd c. CE - 7th c. CE Kofun (Tomb period) 古墳 592 - 710 Asuka 飛鳥 710-794 Nara 奈良 794 - 1185 Heian 平安 1185 - 1333 Kamakura 鎌倉 Nanboku-chō 1333 - 1392 (Southern and Northern Courts period) 南北朝 1392 - 1573 Muromachi 室町 1573 - 1603 Azuchi-Momoyama 安土桃山 1603 - 1868 Edo 江戸 1868 - 1912 Meiji 明治 Era names (Nengō) in Edo Period There were several era names (nengo, or gengo) in Edo period (1603 ~ 1868) and they are sometimes used in the description of the old books and materials, especially Week 2 and Week 4. Here is the list of the era names in Edo period for your convenience; 1 SINO-JAPANESE INTERACTIONS THROUGH RARE BOOKS KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University Timelines and Maps Start Era name English Start Era name English 1596 慶長 Keichō 1744 延享 Enkyō -

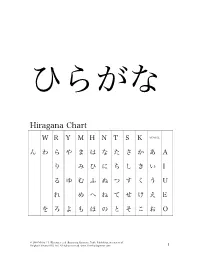

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb.