Public Libraries and New Media: a Review and References. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., Calif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First National Bank Whosoever Does Not Bear His Grees in 24 Hours, in One Hour It FOR

•0 _■,..■ traffic volume year in history and the highest op- SV Bnmmsuttle IfrralO erating efficiency and economy ever attained. THE FIRE WORSHIPER l A reminder that the bus companies operating In July 4, 1892 _Eatabliahed 48 states have not lessened the freight earnings of the Entered u second-class matter In the Postofflc® rail systems of the republic. Prophets of pessimism Brownsville, Texas. in the not remote past predicted that the railways would be out of business and • THE E^OWNSVILLE HERALD PUBLISHING put by freight passeng- er bus lines. Well, the offilcal figures demonstrate COMPANY that the prophets of pessimism are prophets of bunk Subscription Rates—Dally and Sunday (7 Issues) One Year . $9.00 Where Prohobition Prohibits Six Months .$4.50 Federal Judge Duval West of the United States dis- Three Months.$2.25 trict court gave Romero Domingues, who pleaded One Month... .75 guilty to charges of having violated the prohibition laws, a sentence of five years in the federal peni- MEMBER OF THE ASSOCIATED PRESS tentiary in Leavenworth and a fine of $500. This was The Associated Press is exclusively entitled to the use the heaviest penalty ever Inflicted in a liquor case In for publication of all news dispatches credited to It or the western district of Texas. Records show that not otherwise credited In this paper, and also the Romero had appeared before Judge West four times local news published herein. and that he had served a year and a day in Leaven- worth in 1927 on a narcotic charge conviction. This Harlingen Office. -

CHLA 2017 Annual Report

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Annual Report 2017 About Us The mission of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is to create hope and build healthier futures. Founded in 1901, CHLA is the top-ranked children’s hospital in California and among the top 10 in the nation, according to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll of children’s hospitals for 2017-18. The hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute and is one of the few freestanding pediatric hospitals where scientific inquiry is combined with clinical care devoted exclusively to children. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is a premier teaching hospital and has been affiliated with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California since 1932. Table of Contents 2 4 6 8 A Message From the Year in Review Patient Care: Education: President and CEO ‘Unprecedented’ The Next Generation 10 12 14 16 Research: Legislative Action: Innovation: The Jimmy Figures of Speech Protecting the The CHLA Kimmel Effect Vulnerable Health Network 18 20 21 81 Donors Transforming Children’s Miracle CHLA Honor Roll Financial Summary Care: The Steven & Network Hospitals of Donors Alexandra Cohen Honor Roll of Friends Foundation 82 83 84 85 Statistical Report Community Board of Trustees Hospital Leadership Benefit Impact Annual Report 2017 | 1 This year, we continued to shine. 2 | A Message From the President and CEO A Message From the President and CEO Every year at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is by turning attention to the hospital’s patients, and characterized by extraordinary enthusiasm directed leveraging our skills in the arena of national advocacy. -

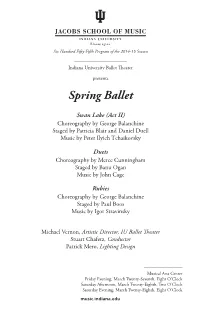

Spring Ballet

Six Hundred Fifty-Fifth Program of the 2014-15 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Duets Choreography by Merce Cunningham Staged by Banu Ogan Music by John Cage Rubies Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Paul Boos Music by Igor Stravinsky Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Seventh, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Eighth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine* ©The George Balanchine Trust Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Original Scenery and Costumes by Rouben Ter-Arutunian Premiere: November 20, 1951 | New York City Ballet City Center of Music and Drama Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Violette Verdy, Principal Coach Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Odette, Queen of the Swans Raffaella Stroik (3/27) Elizabeth Edwards (3/28 mat ) Natalie Nguyen (3/28 eve ) Prince Siegfried Matthew Rusk (3/27) Colin Ellis (3/28 mat ) Andrew Copeland (3/28 eve ) Swans Bianca Allanic, Mackenzie Allen, Margaret Andriani, Caroline Atwell, Morgan Buchart, Colleen Buckley, Danielle Cesanek, Leah Gaston (3/28), Bethany Green (3/28 eve ), Rebecca Green, Cara Hansvick -

TV Theme Songs

1 TV Themes Table of Contents Page 3 Cheers Lawman - 38 4 Bonanza Wyatt Earp - 39 5 Happy Days Bob Hope - 4 6 Hawaii 5-O Jack Benny - 43 6 Daniel Boone 77 Sunset Strip - 44 7 Addams Family Hitchcock - 46 8 “A” Team Kotter - 48 9 Popeye You Bet Your Life - 50 11 Dick Van Dyke Star Trek - 52 11 Mary Tyler Moore Godfrey - 54 13 Gomer Pyle Casper - 55 13 Andy Griffith Odd Couple - 56 14 Gilligan’s Island Green Acres - 57 15 Davey Crockett 16 Flipper Real McCoys - 59 16 Cheyenne Beverly Hill Billies - 60 17 The Rebel Hogan's Heroes - 61 17 Mash Love Boat - 62 19 All in the Family Mission Impossible - 63 20 Mike Hammer McDonalds - 65 21 Peter Gunn Oscar Myers - 65 22 Maverick Band Aids - 65 23 Lawman Budweiser - 66 24 Wyatt Earp 24 Bob Hope 26 Jack Benny 27 77 Sunset Strip 27 Alfred Hitchcock 28 Welcome Back Kotter 28 You Bet Your Life (Groucho Marx) 29 Star Trek 31 Arthur Godfrey 31 Casper the Friendly Ghost 32 Odd Couple 32 Green Acres 33 The Real McCoys 34 Beverly Hillbillies 35 Hogan’s Heroes 35 Love Boat 36 Mission Impossible 37 Mr. Ed 37 Dream Alone with Me (Perry Como) 2 2 Cheers - 1982-1993 – Music by Gary Portnoy & Judy Hart Angelo This popular theme song was written by Gary Portnoy and Judy Hart Angelo when both were at crossroads in their respective careers. Judy was having dinner and seated next to a Broadway producer who was looking for someone to compose the score for his new musical. -

Jails: Inadvertent Health Care Providers How County Correctional Facilities Are Playing a Role in the Safety Net Contents

A report from Jan 2018 Astrid Riecken/The Washington Post/Getty Images Jails: Inadvertent Health Care Providers How county correctional facilities are playing a role in the safety net Contents 1 Overview 3 How jails developed a role in the health care safety net 7 The challenges of providing jail health care 9 Designing jail health care delivery systems Organizational models 9 Staffing 16 Ensuring quality 19 21 Crafting RFPs to obtain high-value care 23 Planning for a healthy re-entry period Facilitating health coverage 23 Continuing care post-release 25 Sharing health information 26 Using jails to combat the opioid epidemic 26 28 An evolving landscape 28 Conclusion 29 Methodology RFP analysis 29 Case studies 31 32 Endnotes ii The Pew Charitable Trusts Susan K. Urahn, executive vice president and chief program officer Michael Thompson, vice president, state and local government performance Project Team Kil Huh, senior director Alexander Boucher Frances McGaffey Matt McKillop Maria Schiff External reviewers This report benefited from the insights and expertise of two external reviewers: Ronald Harling, jail superintendent, Monroe County, New York, and Natalie Ortiz, Ph.D., senior research analyst, National Association of Counties. Although these experts have found the report’s approach and methodology to be sound, neither they nor their organizations necessarily endorse the report’s findings or conclusions. Acknowledgments Tim Cordova and Sandra Nwogu provided invaluable assistance with collecting and verifying data. We would like to thank Marc Stern, M.D., and Angela Goehring for their insight and guidance. We also thank Bernard Ohanian, Jeremy Ratner, Kimberly Burge, Rachel Gilbert, Steve Howard, Carol Hutchinson, Liz Visser, and Gaye Williams for providing valuable feedback and production assistance on this report. -

Defusing a Dangerous Duo

Summer 2008 | Volume 22 | Issue 3 rrectCare™ C The magazine of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care Defusing a Dangerous Duo Nurse Consultants Help Integrate Care How Food Budget Cuts Can Improve Diets National Commission on Correctional Health Care 1145 W. Diversey Parkway, Chicago, IL 60614 Presented by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care and the Academy of Correctional Health Professionals National Conference on Correctional Health Care October 18–22, 2008 | Chicago, Illinois Full page Ad 8” x 10 1/2” Page 2 Set to take place in Chicago’s bustling and beautiful downtown, the 2008 National Conference will inspire attendees to ele- vate their standards of professionalism and health care delivery. Join 2,000 colleagues at this multifaceted forum that offers over 100 concurrent sessions plus many other opportunities to extend your knowledge and your professional network. For more information email [email protected], call 773-880-1460, or visit www.ncchc.org. Nat Conf CC FP Ad 08.indd 1 4/30/08 4:42:59 PM Summer 2008 | Volume 22 | Issue 3 CorrectCare™ is published quarterly by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, a not-for-profi t organization whose mission is to improve the quality of health care in our nation’s jails, prisons and juvenile confi nement facilities. ™ NCCHC is supported by 38 leading national organizations representing the fi elds of health, law and corrections. C rrectCare BOARDBOARD OF DIRECTORS RobertRobert E. Morris, MD ((Chair)Chai Society for Adolescent MedicineMedicin Joseph V. Penn, MD, CCHP (Chair-Elect)(Chai American Academy of Child & AdolescentAdolesce Adolescenn Psychiatry George J. -

Jonathan Emery

The SearcherA PUBLICATION OF THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 2015, VOLUME 52, NO. 3 Adventure Jonathan Emery Patrol Boats Stop on the Mekong River The Little Engine that Could Okazaki Family Graveyards and Gravestones A Proof of Ancestry Local History is Your History Spotlight on Volunteers The Southern California Genealogy Society has no paid About SCGS staff. Everything is done by volunteers. The Library hosts many genealogy interest groups and other events with groups and con- Southern California Genealogical Society tact information listed below. For specific dates and time each group meets, please refer to the three-monthcalendars published 417 Irving Drive, Burbank, California 91504-2408 in each issue of The Searcher or check the online calendar at the (818) 843-7247 or (818) THE SCGS SCGS website at www.scgsgenealogy.com. FAX: (818) 843-7262 E-mail: [email protected] Group Contact Info Website: www.scgsgenealogy.com Library Hours 1890 Project Louise Calaway Monday: Closed [email protected] Tuesday: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • 3rd Tuesday: 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. African American Interest Group Charlotte Bocage Wednesday-Thursday: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. [email protected] Friday: 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Chinese Family History Group Bo-gay Tong Salvadore First & Second Sundays of SoCal [email protected] Third & Fourth Saturdays Anna Gee [email protected] of Each Month: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. DNA Interest Group Bonny Cook, Alice Fairhurst Membership Dues DNA Administrator’s Roundtable Kathryn Johnston 1 Year Individual: $35 1 Year Joint*: $50 [email protected] 2 Years Individual: $65 2 Years Joint*: $90 Family Tree Maker Users Group Dick Humphrey 1 Year International Membership (w/mailing): $70 U.S. -

AIMING STRAIGHT Dear EDITOR

AIMING STRAIGHT dear EDITOR, EDITOR'S NOTE: This Is your page-made available to anyone In your " Arrow Hook" paragraph (Summer '86)on alumna/alumnus, wisblng to comment on articles, the magazine, or any topic of Interest you do not mention pronunciation, and so many college graduates still to our readers. Letters must be signed with full name, address, and fumble there. chapter. We reserve tbe right to edit as needed to space requirements Some years ago I wrote-for a Convention Dally as I recall-a brief and content. msf verse a la "Thirty Days Hath September" to clarify thiS , and it might be worth repeating: Hooray for C.O. When one speaks of you and me, After graduating from Virginia Tech in 1984, I have married and Sisters, we are alumnae (nee) moved three times in the course of one year. Despite my various But with our husbands, you and I addresses, Pi Beta Phi Central Office and The Arrow have diligently Together are called alumni (ni). kept up with me, and for that I am extremely grateful. .. Sic biscuitus distintegrat." ° When I was in Tulsa, OK, I notified Central Office of my new address Many thanks for your good work. Marion Wilder Read and asked who I could get in touch with to join the Tulsa Alumnae Pi Phis. The answer came back within a few days, and I enjoyed eight North Dakota Alpha months with the Tulsa Pi Phis! Morristown, NJ °That's the way the cookie crumbles! I recently moved back to Virginia and, in the process, didn't receive the summer edition of The Arrow. -

The Magazine of Doane Academy Fall 2019 George Mesthos

IV Y LEAVES The Magazine of Doane Academy Fall 2019 George Mesthos, ‘05 In the Nation’s Service Table of Contents Letter from the Headmaster 3 In the News 5 Read about the exciting events and programs we shared in the spring and summer of 2019. George Mesthos ‘05: from Doane to Dhaka and Beyond 14 Doane Academy Legacies 16 St Mary’s Hall: Brighton and Burlington From the Archives, Part III 18 Class Notes 20 Annual Report 32 IVY LEAVES COLLABORATORS WRITERS EDITORS George B. Sanderson Pam Heckert ‘67 Elizabeth Jankowski Bonnie Zaczek Kathleen L. Keays ‘88 top left: Upper school spring play, Firebirds Jack Newman top right: Middle school students compete in the annual PHOTOGRAPHERS DESIGNER cardboard boat race bottom left: Doane’s annual Taste of the Best event, David Baldwin Katie Holeman which this year raised a record amount Jack Newman Letter from the Headmaster One year ago, the Board of Trustees at Doane Academy approved Right Onward 2023, our school’s new Strategic Plan. As we work to implement the priorities included in the plan, this summer we surveyed our young alumni to get a sense of the impact Doane has had on their lives both in college and beyond. The response to our survey was excellent, and I’d like to thank all of our alumni who took the time to share with us their thoughts. The data we collected—the second survey we have administered over the past four years—are a valuable tool in our assessment of what we do especially well and areas where we can improve. -

A History Long Overdue: the Public Library and Motion Pictures

1 Chapter 5 A History Long Overdue: The Public Library and Motion Pictures Jennifer Horne In a report written in 1870 on the state of the Boston Public Library, the first municipally-funded library system in the United States, an examiner observed that "the assembled crowd is often motley. But, the more motley, the more various and dissimilar its ingredients, the better the proof of the widespread influence of the library. Rich and poor assemble together and alike in this narrow dispensary, and a great many of them too."1 Striking, at first, for how the picture of class and social mixing stands out against Americans' present experience of stratification in central and branch libraries, it also recalls characterizations of early moviegoing audiences issued by Progressive era reformers. To the author of the Boston report, whose job was to recommend building a new library, the public library's civic body was just a crowd. Largely unconcerned with books and reading, or the private and contemplative reader, the report's recommendations hinged on the social production of space. Championing the library's capacity for creating a heterogeneous public, the observer set the disorder of that utterly modern mass against the ordered shelves of new and old knowledge.2 This view of the library as a utopian social space was and is persistent. Hugo Münsterberg, professor of psychology at Harvard University (and later, of course, the author of one of the first psychological studies of film), turned a social-scientific eye to this cultural apparatus in his book The Americans (1904), celebrating the American 1 Fred Lerner, The Story of Libraries (New York: Continuum, 1995), 146, 247n6. -

View / Open UOCAT Jun 1967 Grad Conv.Pdf

OFFICIAL DEGREE LIST Approved by the University faculty and the State Board of Higher Education Commencement Program UNIVERSITY OF OREGON NINETIETH ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT HAYWARD fiELD SUNDAY, JUNE 11, 1967 Oregon Pledge Song Fait Oregon, we pledge to thee Our honor and fidelity. Both now and in the years to be, A never failing loyalty. Fair Oregon, thy name shall be Written high in liberty. Now, uncovered, swears thy every son Our pledge to Oregon. For not<!s "" a.udetnic cootumc, tum to [laid<! b&ck COTe<. ACADEMIC COSTUME The history of academic dress aoes back .event a:nturies, to the chill universities where cap and gowu and hood were needed for <:overing and warmth. Subse quently this has become a cu-emooial costume, with certain staodardiud features. For example, stte\"eS in the bachelor's gown aTe pointed. in the master's gown are oblong, in the doctor's gown are bell-shaped. Only the doctor'. gown hu velvet facing. The hood is lined with the official colors of the degree-«JDferring imtitution; for the University of Oregon these are lemon yellow and green. 'The ouuide trimming of the hood lignifies the subject in which the degree was con· ferred, as follows; Maize Agriculture White Arts, Letters, Hutnanities D<2b Commerce, Accountancy, Business Ulac Dentistry Cop"" Economics Light Blue Education 0=", Engineering Brown Fine Arts, including Architecture R~... Forestry Crimson Journalism Purple "'w Lonon Library Sciell~ G,~ Medicine Pink Music Apricot Nursing Silver Gr-ay Oratory, Speccli Olive Green Phann>ey Dark Blue Philosophy ~eGreen Physical Educ::ation Pc:acock Blue Public Administration, including Foreign Service Salmon Pink Public Health Golden YeUow Sci~ Citron Social Work 5=1" Theology Gcay Vmrinary Science At the University of Oregon it is CU5tomary to hood docton' candklates on the platform. -

Press Herald

NOVfMBEl 18, 1964 Hear Mrs. Hansrn. 1 was help settle a dollar hot bo-Ite charity. On second repeat the performance they .enjoys them C-4 WUSS-HBHAIO there too. When I talked to twern my cousin and me. I thought, send two hueks. did on "Shindig"? Darlene know of no ^J-Youth Groups • m Lucy, she was complaining lniaintj|jn <Tpss 1?nrker js t |u, Boyle, Austin, Texas. | from onc sinRPr for other T ». 1 . about a wicked headache. Does former husband of l«ina Tur- Hear Sir: My favorite singer. singers. Invited to that help? Hollywood . « ner and that it was his (laugh Anita Brvant, doesn't do Dear Darlene: Their con- ... tor who stabbed.lohnnv Stom- those soft-drink commercialS'tract with Jack (iood. pro- . Western Show Dear: Sir: Whv is Paula . ., ii, -.,< on TV anymore but whenever I Hucer of the show, prohibits Mr. < oulrt you tell me il il^ttalourinV.Hhlhel'^^"'^ Nr!so'n she Bursts on other shows, or anv repeat showings. But J«k -'«hn l-ennon wears a wig-?-; hevcral lorrance ynuth road company of "Barefoot in "'.rx kp' - J '"u sure Kathleen O'Brien, Rockland.jgroups will attend the Mth the Park" ..". but not appear- nko . -v *- 1 makes personal appearances, (P||s nu> jt |on|(,, ||kr « Reporter she never passes up an op- (hing for ABC-TV to beam'Mass [Annual Great Western Expo- ] ing in it? Allinson Lucas. portunity to plug that com- (nr half-hour special the sition A Livestock Show as NY. Baysid*. Dear Jane- You're both pan\'s t'r,odu^ Wnl sh* btl |Beatles pre-taped In Kngland guests of the hoard of direc- Dear Alllson: Her hushand.