Lasalle Macpherson.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermitage Academy

Hermitage Academy Performance Report 2013-14 1. Curriculum 2. Attainment and Achievement 3. Learning and Teaching 4. Support 5. Ethos 6. Resources 7. Management and Leadership Curriculum Vision Statement Hermitage Academy aims to provide an education for all of our young people which will enable them to achieve their potential, experience success and be well prepared for life beyond school. G.T. Urie Headteacher Jan 2014 Curriculum Under a Curriculum for Excellence the school now offers a Broad General Education from S1 to S3. This allows pupils to be fully engaged in the curriculum and allows for breadth and depth of study. Pupils are not resentful of having to do certain subjects, which may have been the case under the old curriculum model. In Senior School the students have a broad range and level of subjects to choose from. Courses are available for all students and range from Access to Advanced Higher. The school has also introduced Enhancement Courses for students in Senior School. All these measures mean that students are far more engaged with the school and are aiming for positive destinations. Curriculum for Excellence Update We have a successful transition from primary to secondary – through the Hooked on Hermitage transition project - which leads into a broad general education through S1 to S3 with all subjects available to all pupils. In Junior School - S1 to S3 courses are constructed around the Curriculum for Excellence Experiences and Outcomes taking pupils through Level 3 and towards Level 4 in S3 with Inter- disciplinary Learning being delivered through a number of whole school initiatives – Hooked on Hermitage , Health Month , etc. -

Incident Statistics

APPENDIX 2 Strathclyde Fire Brigade Community Safety Section (North Command) IINNCCIIDDEENNTT SSTTAATTIISSTTIICCSS FIRES WITHIN SCHOOL/ EDUCATIONAL PREMISES ARGYLL AND BUTE The under noted figures represent the total number of reportable fire incidents within educational establishments attended by Strathclyde Fire Brigade in the Argyll and Bute area during the period January 2001 until present. YEAR DATE ADDRESS 2001 01/03/2001 11:29:14 Newton Primary School, Bowmore, Islay 12/09/2001 19:09:57 Dunoon Grammar School, Ardenslate Rd, Kirn, Dunoon 01/10/2001 12:14:17 Rothesay Academy, Westland Rd, Rothesay, Bute 3 Incidents 2002 30/09/2002 20:37:30 Hermitage Academy, Campbell Dr, Helensburgh 21/10/2002 14:44:37 Glencruitten Hostel, Dalintart Dr, Oban 2 Incidents 2003 21/02/2003 13:15:48 Tobermory High School, Albert St, Tobermory, Mull 08/12/2003 08:43:54 Career Scotland Centre, 4 Castlehill, Campbeltown 2 Incidents 2004 0 Incidents Total 7 Incidents F:\moderngov\data\published\Intranet\C00000190\M00001746\AI00017606\SprinklersSystemAppendix20.doc APPENDIX 2 In addition for the same period minor / secondary fires were attended by the Brigade as follows. YEAR DATE ADDRESS 2001 20/03/2001 13:50 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 19/05/2001 17:02 HERMITAGE PRIMARY SCHOOL 21/05/2001 13:07 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 24/05/2001 13:50 LOCHGILPHEAD HIGH SCHOOL 20/06/2001 20:24 DUNOON PRIMARY SCHOOL 09/10/2001 20:15 TARBERT ACADEMY 09/10/2001 20:15 TARBERT ACADEMY 7 Incidents 2002 27/01/2002 01:30 HERMITAGE ACADEMY 24/06/2002 22:50 DUNOON PRIMARY SCHOOL 25/06/2002 19:31 INNELLAN SCHOOL 3 Incidents 2003 13/05/2003 13:00 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 25/09/2003 10:48 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 08/11/2003 01:32 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 3 Incidents 2004 18/01/2004 02:54 HERMITAGE ACADEMY 26/02/2004 13:32 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 26/02/2004 15:49 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 29/02/2004 15:31 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 25/06/2004 22:20 KIRN PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 Incidents Total 18 Incidents The spread of times throughout the day reinforces the argument that security measures do not provide protection from incidents taking place during the day. -

Schools Inspected up to Week Ending 1 June 2018

Schools inspected up to week ending 1 June 2018 This data relates to local authority and grant-maintained schools in Scotland. The data records the date of the last inspection visit for schools up to the week ending 1st June 2018. Where an inspection report has not yet been published this is indicated in the data. The data relates to general inspection activity only. This means the main inspection visit that a school receives. The list of schools is based on the Scottish Government's list of schools open as of September 2016: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/School-Education/Datasets/contactdetails For those schools listed which do not have an inspection date, this is due to a number of factors, including changes to the school estate, local circumstances, or the provision being reported in another inspection unit (GME units or support units). School details (as at September 2016, Scottish Government) Date of last inspection (as at week end 01/06/2018) SEED number Local authority Centre Type School Name Primary Secondary Special Inspection date mmm-yy 5136520 Highland Local Authority Canna Primary School Primary - - May-02 6103839 Shetland Islands Local Authority Sandwick Junior High School Primary Secondary - Sep-02 6232531 Eilean Siar Local Authority Back School Primary - - Nov-02 8440549 Glasgow City Local Authority Greenview Learning Centre - - Special Sep-03 5632536 Scottish Borders Local Authority Hawick High School - Secondary - Sep-03 8325324 East Dunbartonshire Local Authority St Joseph's Primary School Primary - - -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Education and Lifelong Learning 1. Our Learning Culture

Community Services Spokesperson’s Report - Education and Lifelong Learning 1. Our Learning Culture – The Role of Coaching and Mentoring Throughout this session the education service has been building a capacity to develop coaching skills within schools and across the service as a whole. This development has been funded by the Scottish Executive with a grant of £35,000 and is central to the Executive’s drive to further develop leadership capacity in Scottish education. This project was progressed on the basis of consultation and collaborative working between colleagues in Argyll and Bute and West Dumbarton education services. We have piloted the practice of coaching with school staff, directorate and quality improvement team members. Schools involved in Argyll and Bute were; Dunoon Grammar, Hermitage Academy, Islay High, Rothesay Academy, Rothesay Primary and Lochgilphead Primary. Six centrally based staff were identified from Argyll and Bute and 6 from West Dumbarton, who would act as a resource to support the training of school based cohorts. From the above schools, 33 staff were involved from each authority. Schools ‘self selected’ and centrally based staff volunteered their involvement. In addition to this, 12 staff from Argyll and Bute and 4 from West Dunbartonshire are currently undertaking a Diploma in Coaching and Mentoring through the Institute of Leadership and Management with Munro Training providing the taught component. The above staff will form the core capacity for sustainable development of the initiative across both authorities. The external critical friend to the project stipulated by the Scottish Executive noted in his evaluation that; “To date, based on the evidence to hand, this project has been a resounding success…the project management team has learned and developed though the process of delivering…the learning gained is being applied n practice ”. -

Kalh Supporter HI Caledonian Mac A' Bhriuthainn Bitaichean-Atseig Nan Ellean Is Chluaidh /Kajor Sponsors ^RBS Eventscotland'

/KaLh Supporter HI CaledonianBitaichean-atseig Mac nan Elleana' Bhriuthainn is Chluaidh /Kajor Sponsors ^RBS EventScotland’ Areyll ^Butei COUNCIL 9 ArgyllEnterprise & the Islands Alba ... a’ toirt thugaibh Mod na bliadhna-sa ... air an telebhisean ... air an reidio ... air an eadar-lion 103.5- 105 FM bbc.co.uk/alba Fon an asgaidh gu: 08000 967050 Gach soirbheachadh do na farpaisich agus don h-uile duine a tha an sas! MnE is one of Scotland's leading independent television production companies with an outstanding reputation for producing high quality broadcast programming. mne See MnE: www.mnetelevision.com telibhisean LevelGlasgow 3, Pentagon Business Centre. 2Skye Pairc nan Craobh Estate, 3BG3 WashingtonBAZ Street. Glasgow, IV4SBroadford, SAP Isle of Skye, t:e: [email protected] 240 0000 t:e: [email protected] S2Q ISO 2 A' cruthachadh chothroman dhan Ghaidhlig ■ othrothroman obrach sa Ghdidhlig a cOrsaichean fein leasachaidh 'brosnachadh Gdidhlig am A" measg an digridh didhlig sa Choimhearsnachd G “Failte chridheil oirbh gu Mod Dhiin Omhain 2006” Tuilleadh fiosrachaidh aig: www.cnag.org.uk 'ModNaiseanta (RiogfiaiC (Dim OmUain 2006 TdiCte 6ho (DickjWafsh Tear-gairm ComataicCh Mdcf (Dhiin Omhain 2006 OEVD MILK kAiLKE -a CHAltRDEAN As Cetf Coimfiearsnacfd(Dfiun Omhain is ChdmhaiCis Comhairie <Earra (jhdidheiC is (Bhdidagus mo cho-oihrichean air Comataidh ionadada’ Mhdidtha sinn a’ cur fdiCte hhldth oirhhgu ar hade agus gu MddNdiseanta (Rioghad2006. dha sinn air Ceth fortanach cothrom fhaighinn aoigheachd a thoirt dhan Mhod Ndiseanta agus tha sinn Can dhdchasach, Ce ar n-udachaidhean a-nis suidhichte, inhheachd ar n-diteachan farpais, agus ar moCdidhean a thaohh nafeise, a hhios a ’ gahhada-steach taghadhfarsaing de thachartasan cuCtarad, cdmhCa ri cdirdeas ar Coimhearsnachd, gun codean sinn ar n-amas am Mdda dheanamh eadhon nos fhedrr ann an 2006 agus seadtainn aon uair ede gur e sdr dite a th’ ann an (Dim Omhain airson Ceithidde dhfheis chuCtarad, chudromach ndiseanta. -

We Propose a Methodology Capturing the Perception of Geogra

Hard to reach communities and a hard to reach university Abstract: We propose a methodology capturing the perception of geographical, monetary and transportation distance between secondary state schools in some Scottish remote communities and a hard to reach university located in a small town on the north-east coast of rural Fife, i.e. the University of St Andrews. The location of St Andrews and the absence of a railway station mean that it is often interpreted as being geographically isolated. As a result, the University of St Andrews is frequently perceived as hard to reach. We show that by combining representations in terms of mileage, journey duration and fare we can create an index that reflects the difficulty of geographical access to the University of St Andrews from these Scottish communities. This index is not dependent on the local authority in which the institutions are located, nor on the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation associated with each institution datazone, nor on the percentage rate of progression to higher education from these secondary schools. It is dependent on how distance may be perceived in terms of geographical access, monetary costs and transportation. This index represents an alternative way of measuring remoteness. It could be easily (1) extended to many higher education institutions and (2) integrated into a contextualised admissions system in which applicants from Scottish remote communities would be signalled. 1 1. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to propose a methodology capturing the perception of distance between secondary state schools in some Scottish remote communities and a hard to reach university located in a small town on the north-east coast of rural Fife, i.e. -

WHAN Publication Final Printer

The Working in Health Access Network Interim Report and Discussion Paper January 2009 Foreword The Working in Health Access Network (WHAN) exists to increase interest in a career in health amongst school pupils. The focus of WHAN is to increase their aspirations and provide information concerning courses in healthcare in both universities and colleges - as well as introducing them to a wide range of exciting options for the future. The National Health Service (NHS) is the largest employer in the country and is central to the well being of the economy at large. At the heart of any strong and confident organisation is a knowledgeable, professional and motivated workforce. WHAN works directly with the next generation of health workers to ensure that the health sector is staffed by committed individuals with the skills required to help make Scotland a healthier, stronger, fairer, smarter and wealthier place in which to live, study and work. This report portrays the development of the WHAN network so far. It also raises questions and challenges for the future. As the current phase of WHAN continues until this July, the complete statistical analysis is not yet available. Nevertheless, there is considerable creativity, innovation and success in WHAN school and college activities. This report is an introduction to these activities; more detailed outcomes will be available from the middle of 2009. The project has forged a successful partnership. It grew out of the Working in Health Access Programme (WHAP) that was aimed particularly at medicine and veterinary medicine. The need to diversify to other health professions became apparent in order to fulfil the aspirations of young people, to provide realistic ambitions for them and, also, to be more cost effective. -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

List of Schools in Scotland

List of Schools in Scotland This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 A-C at National 5 and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 or 0141 280 2240 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Aberdeen College Aberdeen City Please check your secondary school Please check your secondary school Aberdeen Grammar School Aberdeen City 5 A/Bs at National 5 FSM Aboyne Academy Aberdeenshire 4 A/Bs at National 5 FSM Airdrie Academy -

Community Services Newsletter

ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL JUNE 2012 COMMUNITY SERVICES NEWSLETTER EDUCATION Getting Hooked on Hermitage’ Activity Day On Friday 18th May around 260 enthusiastic primary 7 pupils from local primary schools across Helensburgh and Lomond came together for a day of team building and sports. The event was organised by Active Schools Coordinators Martin Caldwell and Sean McNee and was hosted at Hermitage Academy. The Active Schools physical activity day is included as part of the wider ‘Hooked on Hermitage’ transitional programme and was opened with a presentation from Mr Morgan, Depute Head at Hermitage Academy. Pupils were divided into groups prior to arriving at the event, allowing the children to mix with other primary 7 pupils they didn’t know and make new contacts prior to their transition to Hermitage Academy after the Summer Holidays. Half the day was spent taking part in a range of fun team building sessions, with the rest of the day dedicated to more strenuous physical activity and sports. This year the sports sessions included Tag Rugby, Shinty, Fun Football, Dodge Ball, Basket ball and Paralympic sport Boccia. The weather managed to stay dry allowing the Shinty and Rugby to take place outdoors and meant the successful event was enjoyed by all. General feedback from the pupils highlighted that many new friendships had been made on a day filled with fun physical activity and team building. Active Schools would like to thank Helensburgh and Lomond Rugby coach Kane Greggain, Stewart Maule, staff from Hermitage Academy PE department and all the teachers/ volunteers who helped with activities on the day. -

Addition Added by Simon Cochrane-Mills to Work Out

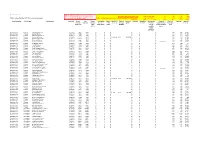

Return to Contents 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Bob said capacity 140 pupils only 1550 Increase pop. 45 90 135 180 Table 9. School Estates 2011 - full school level dataset School budget to be reduced by 30million per year from fife council re 140 Total Pupil 1410 1455 1500 1545 2012 Total 1410 91% 91% 94% 97% 100% Local Authority School type School name Seedcode Gross Site Shared Community Rebuilt New build Funded Value of Condition Suitability Investment Planned Pupil roll Capacity Capacity Internal Curtilage Campus Services 0=No or refurb through Works of estate Plans to completion date September Percent Floor area 0=No 0=No 1=Yes 1=Yes PPINPD change of improvement 2010 1=Yes condition works and/or suitability 0=No 1=Yes Aberdeen City Primary Abbotswell School 5237521 3052 28207 0 0 0 . B C 0 . 203 300 67.667 Aberdeen City Primary Airyhall School 5237629 4102 17571 0 0 0 . A A 0 . 311 360 86.389 Aberdeen City Primary Ashley Road School 5237823 3155 7203 0 0 0 . B C 0 . 386 415 93.012 Aberdeen City Primary Braehead School 5234026 3477 10738 0 0 1 New Build NPD 6059000 A A 0 . 161 279 57.706 Aberdeen City Primary Bramble Brae School 5238129 1528.7 13718 0 0 0 . B B 0 . 165 198 83.333 Aberdeen City Primary Broomhill School 5238226 2996 5787 0 0 0 . B B 0 . 331 450 73.556 Aberdeen City Primary Bucksburn School 5234220 1446 9389 0 0 0 . C B 1 30/09/2012 121 180 67.222 Aberdeen City Primary Charleston School 5246423 1904 13755 0 0 0 .