Access to Higher Education for Rural Communities an Exploratory Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermitage Academy

Hermitage Academy Performance Report 2013-14 1. Curriculum 2. Attainment and Achievement 3. Learning and Teaching 4. Support 5. Ethos 6. Resources 7. Management and Leadership Curriculum Vision Statement Hermitage Academy aims to provide an education for all of our young people which will enable them to achieve their potential, experience success and be well prepared for life beyond school. G.T. Urie Headteacher Jan 2014 Curriculum Under a Curriculum for Excellence the school now offers a Broad General Education from S1 to S3. This allows pupils to be fully engaged in the curriculum and allows for breadth and depth of study. Pupils are not resentful of having to do certain subjects, which may have been the case under the old curriculum model. In Senior School the students have a broad range and level of subjects to choose from. Courses are available for all students and range from Access to Advanced Higher. The school has also introduced Enhancement Courses for students in Senior School. All these measures mean that students are far more engaged with the school and are aiming for positive destinations. Curriculum for Excellence Update We have a successful transition from primary to secondary – through the Hooked on Hermitage transition project - which leads into a broad general education through S1 to S3 with all subjects available to all pupils. In Junior School - S1 to S3 courses are constructed around the Curriculum for Excellence Experiences and Outcomes taking pupils through Level 3 and towards Level 4 in S3 with Inter- disciplinary Learning being delivered through a number of whole school initiatives – Hooked on Hermitage , Health Month , etc. -

484 Carrick Castle

484 Carrick Castle - Dunoon Monday to Friday from 1st July 2021 Note: CM CNM NSch CTH NSch CHF CMTW Service: 484 484 484 484 484 484 484 Carrick Castle 0710 0710 0820 1224 1454 1615 1720 Lochgoilhead, Car Park 0727 0727 0837 1241 1511 1632 1737 St Catherines (Arr) 0747 0747 0857 1301 1531 1652 1757 St Catherines (Dep) 0747 0747 0857 1301 1531 1652 1757 Strachur, The Bay 0754 0754 0903 1307 1537 1658 1803 Strachur, The Clachan 0756 0756 0905 1309 1539 1700 1805 Whistlefield Inn 0804 0804 0913 1317 1547 1708 1813 Benmore Gdns 0812 0812 0921 1325 1555 1716 1821 Kilmun 0815 0815 0924 1328 1558 1719 1824 Sandhaven 0817 0817 0926 1330 1600 1721 1826 Sandbank, Holy Loch Inn 0821 0821 0930 1334 1604 1725 1830 Dunoon, Grammar School 0826 0826 - - - - - School Hostel 0830 - - - - - - Ardenslate Road 0831 - - - - - - Marine Parade - 0828 - - - - - Walkers Garage - - 0935 1339 1609 1730 1835 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0836 0833 0940 1344 1614 1735 1840 Codes: NSch School Holidays 484 Service 484 is operated on behalf of Argyll and Bute Council. School holiday dates are specified by Argyll and Bute Council. No service operates on 25, 26 December or 01, 02 January. CM Schoolday Mondays Only CNM Schooldays Only, Not Mondays CMTW Schoolday Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays Only CHF Schoolday Thursdays and Fridays Only 484 Dunoon - Carrick Castle Monday to Friday from 1st July 2021 Note: Sch NSch CTH NSch CH CF CMTW Service: 484 484 484 484 484 484 484 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0550 0655 1050 1320 1432 1432 1537 Dunoon Grammar School - - - - 1445 1445 1550 School -

Incident Statistics

APPENDIX 2 Strathclyde Fire Brigade Community Safety Section (North Command) IINNCCIIDDEENNTT SSTTAATTIISSTTIICCSS FIRES WITHIN SCHOOL/ EDUCATIONAL PREMISES ARGYLL AND BUTE The under noted figures represent the total number of reportable fire incidents within educational establishments attended by Strathclyde Fire Brigade in the Argyll and Bute area during the period January 2001 until present. YEAR DATE ADDRESS 2001 01/03/2001 11:29:14 Newton Primary School, Bowmore, Islay 12/09/2001 19:09:57 Dunoon Grammar School, Ardenslate Rd, Kirn, Dunoon 01/10/2001 12:14:17 Rothesay Academy, Westland Rd, Rothesay, Bute 3 Incidents 2002 30/09/2002 20:37:30 Hermitage Academy, Campbell Dr, Helensburgh 21/10/2002 14:44:37 Glencruitten Hostel, Dalintart Dr, Oban 2 Incidents 2003 21/02/2003 13:15:48 Tobermory High School, Albert St, Tobermory, Mull 08/12/2003 08:43:54 Career Scotland Centre, 4 Castlehill, Campbeltown 2 Incidents 2004 0 Incidents Total 7 Incidents F:\moderngov\data\published\Intranet\C00000190\M00001746\AI00017606\SprinklersSystemAppendix20.doc APPENDIX 2 In addition for the same period minor / secondary fires were attended by the Brigade as follows. YEAR DATE ADDRESS 2001 20/03/2001 13:50 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 19/05/2001 17:02 HERMITAGE PRIMARY SCHOOL 21/05/2001 13:07 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 24/05/2001 13:50 LOCHGILPHEAD HIGH SCHOOL 20/06/2001 20:24 DUNOON PRIMARY SCHOOL 09/10/2001 20:15 TARBERT ACADEMY 09/10/2001 20:15 TARBERT ACADEMY 7 Incidents 2002 27/01/2002 01:30 HERMITAGE ACADEMY 24/06/2002 22:50 DUNOON PRIMARY SCHOOL 25/06/2002 19:31 INNELLAN SCHOOL 3 Incidents 2003 13/05/2003 13:00 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 25/09/2003 10:48 ROTHESAY ACADEMY 08/11/2003 01:32 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 3 Incidents 2004 18/01/2004 02:54 HERMITAGE ACADEMY 26/02/2004 13:32 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 26/02/2004 15:49 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 29/02/2004 15:31 OBAN HIGH SCHOOL 25/06/2004 22:20 KIRN PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 Incidents Total 18 Incidents The spread of times throughout the day reinforces the argument that security measures do not provide protection from incidents taking place during the day. -

Schools Inspected up to Week Ending 1 June 2018

Schools inspected up to week ending 1 June 2018 This data relates to local authority and grant-maintained schools in Scotland. The data records the date of the last inspection visit for schools up to the week ending 1st June 2018. Where an inspection report has not yet been published this is indicated in the data. The data relates to general inspection activity only. This means the main inspection visit that a school receives. The list of schools is based on the Scottish Government's list of schools open as of September 2016: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/School-Education/Datasets/contactdetails For those schools listed which do not have an inspection date, this is due to a number of factors, including changes to the school estate, local circumstances, or the provision being reported in another inspection unit (GME units or support units). School details (as at September 2016, Scottish Government) Date of last inspection (as at week end 01/06/2018) SEED number Local authority Centre Type School Name Primary Secondary Special Inspection date mmm-yy 5136520 Highland Local Authority Canna Primary School Primary - - May-02 6103839 Shetland Islands Local Authority Sandwick Junior High School Primary Secondary - Sep-02 6232531 Eilean Siar Local Authority Back School Primary - - Nov-02 8440549 Glasgow City Local Authority Greenview Learning Centre - - Special Sep-03 5632536 Scottish Borders Local Authority Hawick High School - Secondary - Sep-03 8325324 East Dunbartonshire Local Authority St Joseph's Primary School Primary - - -

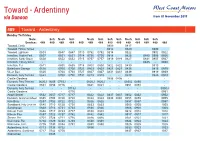

Ardentinny Via Dunoon from 01 November 2019

Toward - Ardentinny via Dunoon from 01 November 2019 489 Toward - Ardentinny Monday To Friday Note: Sch Nsch Sch Nsch Sch Sch Sch Nsch Sch Sch Sch Service: 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 Toward, Castle 0809 0817 Toward, Primary School 0812 0820 0900 Toward, Lightouse 0603 0647 0647 0710 0752 0752 0814 0822 0902 0922 Innellan, Newton Park 0607 0651 0651 0714 0756 0756 0818 0826 0840 0906 0926 Innellan, Sandy Beach 0608 0652 0652 0715 0757 0757 0819 0819 0827 0841 0907 0927 Innellan, Primary School - - - - - - - - - 0845 - 0930 Innellan, Pier 0611 0655 0655 0718 0800 0800 0822 0822 0830 0910 - Balaclava Garage 0616 0700 0700 0723 0803 0803 0827 0827 0835 0915 0935 West Bay 0620 0704 0704 0727 0807 0807 0831 0831 0839 0919 0939 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0624 0708 0708 0731 0813 0813 - - 0843 0923 0943 Castle Gardens - - - - - 0836 0836 - - Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0630J 0655 0715J - 0820J 0820J - - 0850J 0850 - Castle Gardens 0631 0656 0716 - 0821 0821 - - 0851 0851 - Dunoon, Ferry Terminal - - - 0715J - - - - - - 0950J Castle Gardens - - - 0716 - - - - - - 0951 Argyll Street 0632 0657 0717 0717 0822 0822 0837 0837 0852 0852 0952 Dunoon, Grammar School 0635 0700 0720 0720 0824 0824 0840 0840 0855 0855 0955 Kirn Brae 0637 0702 0722 0722 0826 0826 0857 0857 0957 Sandbank, Holy Loch Inn 0645 0710 0728 0730 0833 0833 0905 0905 1005 Sandhaven 0648 0713 0731 0733 0836 0836 0908 0908 1008 Kilmun Turn 0652 0717 0733 0737 0838 0838 0912 0912 1012 Kilmun Pier 0657 0722 0737 0742 0842 0842 0917 0917 1017 Strone, Pier 0701 0726 0741 -

Argyll and Bute Council Community Services Committee

ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL COMMUNITY SERVICES COMMITTEE EDUCATION 27 AUGUST 2020 SQA SCHOOL EXAMINATION MODERATED AWARDS 2020 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 The purpose of this report is to provide an update to Elected Members on the initial outcome of the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) 2020 awards. 1.2 The initial SQA awards outcomes for pupils in academic year 2019/20 are subject to a refined appeals process rather than the traditional clerical check and marking reviews process due to the cancellation of formal SQA examinations as a consequence of COVID-19. Schools will make submissions on behalf of individual pupils to the SQA for consideration within expected timescales. As a consequence small changes to the statistical data contained within this report may occur. Further details of the appeals process are included in Appendix 1. 1.3 It is recommended that the Community Services Committee: a. Considers and notes the outcome of the initial SQA awards for pupils in academic year 2019/20 ie I. National 4 results are above the national outcome by 9.1%. II. National 5 results are above the national outcome by 2.5%. III. Higher results are below the national outcome by 1.3%. IV. Advanced Higher results are above the national outcome by 2.6%. b. Requests that the Executive Director with responsibility for Education provides a further report to the Community Services Committee in December 2020, to allow the consideration of further statistical school and national information, released by Insight (school data analysis tool) in September 2020; and c. Agree that in session 2020/21 attainment and achievement outcomes will be presented to the Community Services Committee, only following release of Insight data which affords full access to statistical school and national information in relation to attainment and achievement outcomes of the young people of Argyll and Bute. -

Argyll & Bute Local Authority 2015/16

CashBack for Communities Argyll & Bute Local Authority 2015/16 About CashBack for Communities CashBack for Communities is a Scottish Government programme which takes funds recovered from the proceeds of crime and invests them into free activities and programmes for young people across Scotland. Inspiring Scotland is the delivery partner for the CashBack for Communities programme, appointed in July 2012. CashBack invests monies seized from criminals under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 back into our communities. Since 2008 the Scottish Government has committed £92 million to CashBack / community initiatives, funding community activities and facilities largely, but not exclusively, for young people. CashBack supports all 32 Local Authorities across Scotland. Sporting and recreational activities / culture / mentoring and employability / community projects. CashBack has delivered nearly 2 million activities and opportunities for young people. Phase 3 of CashBack runs to end March 2017 and is focused on positive outcomes for young people. CashBack for Communities: Aims CashBack activities: . Use the proceeds of crime in a positive way to expand young people’s horizons and increase their opportunities to develop their interests and skills in an enjoyable, fulfilling and supportive way. Are open, where possible, to all children and young people, while focusing resources in those communities suffering most from antisocial behaviour and crime. Seek to increase levels of participation to help divert young people away from ‘at risk’ behaviour, and will aim to increase the positive long-term outcomes for those who take part. Current CashBack Investment . Creative Scotland . YouthLink Scotland . Basketball Scotland . Celtic FC Foundation . Scottish Football Association . Youth Scotland . Scottish Rugby Union . -

489 Toward - Ardentinny

489 Toward - Ardentinny Monday to Saturday from 29th June 2020 Service: 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 Toward, Lighthouse 0752 0822 1022 1222 1422 1622 Innellan, Newton Park 0756 0826 1026 1226 1426 1626 Innellan, Sandy 0757 0827 1027 1227 1427 1627 Beach Innellan, Pier 0800 0830 1030 1230 1430 1630 Balaclava Garage 0805 0835 1035 1235 1435 1635 Dunoon, Ferry 0813 0843 0943 1043 1143 1243 1343 1443 1543 1643 1743 Terminal, Stop 2 Dunoon Ferry 0713J 0820J 0850J 0950J 1050J 1150J 1250J 1350J 1450J 1550J 1650J 1750J Terminal, Stop 2 Grammar School 0718 0825 0855 0955 1055 1155 1255 1355 1455 1555 1655 1755 Kirn Brae 0720 0827 0857 0957 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1557 1657 1757 Sandbank, Holy Loch 0726 0833 0905 1005 1105 1205 1305 1405 1505 1605 1705 1805 Inn Sandhaven 0729 0836 0908 1008 1108 1208 1308 1408 1508 1608 1708 1808 Kilkmun Turn 0731 0838 0912 1012 1112 1212 1312 1412 1512 1612 1712 1812 Kilkmun, Pier 0735 0842 0917 1017 1117 1217 1317 1417 1517 1617 1717 1817 Dunslema Court - - - - 1121 - 1321 - 1521 - 1721 1821 Strone, Pier 0739 0846 0921 1021 1123 1221 1323 1421 1523 1621 1723 Blairmore, Pier 0741 0848 0924 1024 1126 1224 1326 1424 1526 1624 1726 Ardentinny, Hotel 0750 0856 0933 1033 1135 1233 1335 1433 1535 1633 1735 Ardentinny, 0937 1037 1237 1437 1637 Glenfinnart Service: 489 Toward, Lighthouse 1822 Innellan, Newton Park 1826 Innellan, Sandy Beach 1827 Innellan, Pier 1830 Balaclava Garage 1835 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal, Stop 2 1843G Please maintain physical distancing with our drivers and fellow customers. -

AN ATTRACTIVE Waterside PLOT with DETAILED PLANNING

AN ATTRACTIVE WATERSIDE PLOT WITH DETAILED PLANNING CONSENT FOR THE ERECTION OF UNIQUE DETACHED HOME waterside plot shore road, innellan, dunoon, argyll, pa23 7tp The views down the Firth of Clyde are unparalleled and take in the AN ATTRACTIVE WATERSIDE Ayrshire coast. Spectacular sunrises, sunsets and occasional storms provide natural variety. Seals and, very occasionally, porpoises can be PLOT WITH DETAILED seen throughout the year. PLANNING CONSENT FOR Sporting activities abound in the area including excellent walking, sailing, golfing and both freshwater and sea fishing. There is an active THE ERECTION OF UNIQUE sailing club at Toward, which offers both tuition and racing and two further sailing clubs based at Dunoon; the Inverkip Marina, on the DETACHED HOME opposite shore of the Clyde, is within easy reach for repairs, winter storage and yachting supplies. There is a nine hole golf course at Innellan (established in 1891), as well as an 18 hole golf course (Cowal waterside plot GC) at Dunoon. shore road, innellan, dunoon, argyll, Innellan has a highly regarded primary school, a hotel, a pub and a pa23 7tp village store and post office. Dunoon is a busy town, ferry port and Distances seaside resort, offering good local amenities including a hospital, library, leisure centre and a supermarket. Secondary schooling for the area is at Dunoon 4 miles Dunoon Grammar School. Dunoon Ferry Terminal 6 miles Glasgow Airport 30 miles via ferry Description Glasgow 38 miles via ferry The plot occupies a prime gap site in the small village of Innellan. Situated on waters edge, the proposed property has been designed to Viewing maximise the uninterrupted views over the Firth of Clyde. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Education and Lifelong Learning 1. Our Learning Culture

Community Services Spokesperson’s Report - Education and Lifelong Learning 1. Our Learning Culture – The Role of Coaching and Mentoring Throughout this session the education service has been building a capacity to develop coaching skills within schools and across the service as a whole. This development has been funded by the Scottish Executive with a grant of £35,000 and is central to the Executive’s drive to further develop leadership capacity in Scottish education. This project was progressed on the basis of consultation and collaborative working between colleagues in Argyll and Bute and West Dumbarton education services. We have piloted the practice of coaching with school staff, directorate and quality improvement team members. Schools involved in Argyll and Bute were; Dunoon Grammar, Hermitage Academy, Islay High, Rothesay Academy, Rothesay Primary and Lochgilphead Primary. Six centrally based staff were identified from Argyll and Bute and 6 from West Dumbarton, who would act as a resource to support the training of school based cohorts. From the above schools, 33 staff were involved from each authority. Schools ‘self selected’ and centrally based staff volunteered their involvement. In addition to this, 12 staff from Argyll and Bute and 4 from West Dunbartonshire are currently undertaking a Diploma in Coaching and Mentoring through the Institute of Leadership and Management with Munro Training providing the taught component. The above staff will form the core capacity for sustainable development of the initiative across both authorities. The external critical friend to the project stipulated by the Scottish Executive noted in his evaluation that; “To date, based on the evidence to hand, this project has been a resounding success…the project management team has learned and developed though the process of delivering…the learning gained is being applied n practice ”. -

Kalh Supporter HI Caledonian Mac A' Bhriuthainn Bitaichean-Atseig Nan Ellean Is Chluaidh /Kajor Sponsors ^RBS Eventscotland'

/KaLh Supporter HI CaledonianBitaichean-atseig Mac nan Elleana' Bhriuthainn is Chluaidh /Kajor Sponsors ^RBS EventScotland’ Areyll ^Butei COUNCIL 9 ArgyllEnterprise & the Islands Alba ... a’ toirt thugaibh Mod na bliadhna-sa ... air an telebhisean ... air an reidio ... air an eadar-lion 103.5- 105 FM bbc.co.uk/alba Fon an asgaidh gu: 08000 967050 Gach soirbheachadh do na farpaisich agus don h-uile duine a tha an sas! MnE is one of Scotland's leading independent television production companies with an outstanding reputation for producing high quality broadcast programming. mne See MnE: www.mnetelevision.com telibhisean LevelGlasgow 3, Pentagon Business Centre. 2Skye Pairc nan Craobh Estate, 3BG3 WashingtonBAZ Street. Glasgow, IV4SBroadford, SAP Isle of Skye, t:e: [email protected] 240 0000 t:e: [email protected] S2Q ISO 2 A' cruthachadh chothroman dhan Ghaidhlig ■ othrothroman obrach sa Ghdidhlig a cOrsaichean fein leasachaidh 'brosnachadh Gdidhlig am A" measg an digridh didhlig sa Choimhearsnachd G “Failte chridheil oirbh gu Mod Dhiin Omhain 2006” Tuilleadh fiosrachaidh aig: www.cnag.org.uk 'ModNaiseanta (RiogfiaiC (Dim OmUain 2006 TdiCte 6ho (DickjWafsh Tear-gairm ComataicCh Mdcf (Dhiin Omhain 2006 OEVD MILK kAiLKE -a CHAltRDEAN As Cetf Coimfiearsnacfd(Dfiun Omhain is ChdmhaiCis Comhairie <Earra (jhdidheiC is (Bhdidagus mo cho-oihrichean air Comataidh ionadada’ Mhdidtha sinn a’ cur fdiCte hhldth oirhhgu ar hade agus gu MddNdiseanta (Rioghad2006. dha sinn air Ceth fortanach cothrom fhaighinn aoigheachd a thoirt dhan Mhod Ndiseanta agus tha sinn Can dhdchasach, Ce ar n-udachaidhean a-nis suidhichte, inhheachd ar n-diteachan farpais, agus ar moCdidhean a thaohh nafeise, a hhios a ’ gahhada-steach taghadhfarsaing de thachartasan cuCtarad, cdmhCa ri cdirdeas ar Coimhearsnachd, gun codean sinn ar n-amas am Mdda dheanamh eadhon nos fhedrr ann an 2006 agus seadtainn aon uair ede gur e sdr dite a th’ ann an (Dim Omhain airson Ceithidde dhfheis chuCtarad, chudromach ndiseanta.