Report on Best Practices for Successful Community-Based Investments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Tables 2019-20 Prt.Xlsx

English Premier League PosTeam PldWDL GF GA GD Pts Qualification or relegation [ 1 Liverpool (C) 38 32 3 3 85 33 52 99 2 Manchester City[a] 38 26 3 9 102 35 67 81 Qualification for the Champions 3 Manchester United 38 18 12 8 66 36 30 66 League group stage 4 Chelsea 38 20 6 12 69 54 15 66 Qualification for the Europa 5 Leicester City 38 18 8 12 67 41 26 62 League group stage Qualification for the Europa 6 Tottenham Hotspur 38 16 11 11 61 47 14 59 League second qualifying round[b] 7 Wolverhampton Wanderers 38 15 14 9 51 40 11 59 Qualification for the Europa 8 Arsenal 38 14 14 10 56 48 8 56 League group stage[c] 9 Sheffield United 38 14 12 12 39 39 0 54 10 Burnley 38 15 9 14 43 50 −7 54 11 Southampton 38 15 7 16 51 60 −9 52 12 Everton 38 13 10 15 44 56 −12 49 13 Newcastle United 38 11 11 16 38 58 −20 44 14 Crystal Palace 38 11 10 17 31 50 −19 43 15 Brighton & Hove Albion 38 9 14 15 39 54 −15 41 16 West Ham United 38 10 9 19 49 62 −13 39 17 Aston Villa 38 9 8 21 41 67 −26 35 18 Bournemouth (R) 38 9 7 22 40 65 −25 34 Relegation to the EFL 19 Watford (R) 38 8 10 20 36 64 −28 34 Championship 20 Norwich City (R) 38 5 6 27 26 75 −49 21 English Championship Promotion, qualification or PosTeam PldWDL GF GA GD Pts relegation 1 Leeds United (C, P) 46 28 9 9 77 35 42 93 Promotion to the Premier League 2 West Bromwich Albion (P) 46 22 17 7 77 45 32 83 3 Brentford 46 24 9 13 80 38 42 81 4 Fulham (O, P) 46 23 12 11 64 48 16 81 Qualification for Championship 5 Cardiff City 46 19 16 11 68 58 10 73 play-offs[a] 6 Swansea City 46 18 16 12 62 53 9 70 7 Nottingham -

Acquisition Opportunity: Profitable English Football League Two ("EFL Two") Club with Loyal Fan Base

Acquisition Opportunity: Profitable English Football League Two ("EFL Two") Club with Loyal Fan Base "The Company” is an English Football League Two club with loyal fan base near London in the United Kingdom. The EFL has a proud history and was formed over 115 years ago. The purchase includes all tangible and intangible assets associated with the club. The club currently leases its home stadium and operates several food services outlets including walk-up counters, bars and restaurants. The club’s home stadium boasts a seating capacity of over 6,000. Additionally, the purchase includes a variety maintenance equipment and all player contracts.. Key Acquisition Considerations Highlights Business Description $11.770M English Football League (EFL) was formed in 1888 by its twelve founder members and is the 2020 Revenue world's original league football competition. The EFL is the template used by leagues the world over. The EFL is the largest single body of professional Clubs in European football $.706M and is responsible for administering and regulating the EFL, the Carabao Cup and the Papa John’s Trophy, as well as reserve and youth football. The EFL's 72 member clubs are 2020 Cashflow grouped into three divisions: the EFL Championship, EFL League One, and EFL League Two 6.0% League Two Cashflow Margin There are 24 clubs in the EFL League Two. Each season, clubs play each of the other teams twice (once at home, once away). Clubs are awarded three points for a win, one for a draw 115yrs and no points for a loss. Over the season, these points are tallied, and a league table is Time since Inception constructed. -

The Big Mind Footy Quiz Questions

The Big Mind Footy Quiz As part of Mind’s partnership with The English Football League Questions 1 How many clubs make up the three EFL Divisions (The EFL Championship; EFL League One and EFL League Two)? 2 Can you name the two EFL knockout cup competitions? 3 What season was the EFL Cup (The Football League Cup as it was previously known) introduced? 4 And which club won the first EFL Cup? 5 There are five EFL clubs with ‘Rovers’ in their name, can you name them? (A point for each correct Team) 6 Can you name the team who finished the 2005-06 season as The EFL Championship winners with a record points total? (Bonus point for the points total) 7 Who were the first team to win the Football League Title (1888/89 Season) 8 Can you name the three Welsh clubs who play in the EFL? 9 Can you name the two EFL clubs who are based in Cumbria? 10 Who used to play their home games at Highfield Road? 11 Which EFL club are known as The Tractor Boys? The Big Mind Footy Quiz As part of Mind’s partnership with The English Football League Answers 1 72 2 The EFL Cup (currently known as The Carabao Cup) and The EFL Trophy (currently known as The Papa Johns Trophy) 3 1960/61 4 Aston Villa 5 Blackburn Rovers; Bristol Rovers; Doncaster Rovers; Forest Green Rovers; Tranmere Rovers 6 Reading. (Bonus point: 106 points) 7 Preston North End 8 Cardiff, Swansea and Newport County 9 Barrow AFC and Carlisle United 10 Coventry City 11 Ipswich Town . -

The Emirates Fa Cup Season 2021-22 List of Exemptions

THE EMIRATES FA CUP SEASON 2021-22 LIST OF EXEMPTIONS 44 CLUBS EXEMPT TO THIRD ROUND PROPER (PL & EFL Championship) AFC Bournemouth Derby County FC Nottingham Forest FC Arsenal FC Everton FC Peterborough United FC Aston Villa FC Fulham FC Preston North End FC Barnsley FC Huddersfield Town FC Queens Park Rangers FC Birmingham City FC Hull City Reading FC Blackburn Rovers FC Leeds United AFC Sheffield United FC Blackpool FC Leicester City FC Southampton FC Brentford FC Liverpool FC Stoke City FC Brighton & Hove Albion FC Luton Town FC Swansea City FC Bristol City FC Manchester City FC Tottenham Hotspur FC Burnley FC Manchester United FC Watford FC Cardiff City FC Middlesbrough FC West Bromwich Albion FC Chelsea FC Millwall FC West Ham United FC Coventry City FC Newcastle United FC Wolverhampton Wanderers FC Crystal Palace FC Norwich City FC 48 CLUBS EXEMPT TO FIRST ROUND PROPER (EFL League One & League Two) Accrington Stanley FC Fleetwood Town FC Port Vale FC AFC Wimbledon Forest Green Rovers FC Portsmouth FC Barrow AFC Gillingham FC Rochdale AFC Bolton Wanderers FC Harrogate Town FC Rotherham United FC Bradford City FC Hartlepool United FC Salford City FC Bristol Rovers FC Ipswich Town FC Scunthorpe United FC Burton Albion FC Leyton Orient FC Sheffield Wednesday FC Cambridge United FC Lincoln City FC Shrewsbury Town FC Carlisle United AFC Mansfield Town FC Stevenage FC Charlton Athletic FC Milton Keynes Dons FC Sunderland AFC Cheltenham Town FC Morecambe FC Sutton United FC Colchester United FC Newport County AFC Swindon Town FC Crawley -

2021 Season Game Notes

2021 SEASON GAME NOTES HOME PLAYER2021 SCHEDULE INFO DATE OPPONENT TIME RESULT 05/01 vs. New Mexico United 7:30PM CST W, 1-0 05/06 vs. San Diego Loyal 7:00PM CST W, 1-0 05/16 vs. San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST W, 2-1 05/22 @ El Paso Locomotive FC 8:30PM CST L, 1-0 05/29 @ San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST D, 1-1 06/06 @ Miami FC 5:30PM CST W, 4-2 06/12 vs. Real Monarchs SLC 7:00PM CST - 06/16 vs. Austin Bold FC 7:00PM CST - 4-1-1 06/19 @ San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST - 06/25 vs. Tulsa FC 7:30PM CST - AWAY 06/30 vs. El Paso Locomotive FC 7:00PM CST - 07/10 @ Austin Bold FC 8:00PM CST - 07/17 @ Orange County SC 7:00PM CST - 07/24 vs. Austin Bold FC 8:00PM CST - 07/31 @ Phoenix Rising FC 9:30PM CST - 08/04 @ Real Monarchs SLC 9:00PM CST - 08/08 vs. San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST - 08/14 vs. Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC 7:00PM CST - 08/17 @ Austin Bold FC 8:00PM CST - 08/21 @ El Paso Locomotive FC 8:30PM CST - 08/29 @ OKC Energy FC 5:00PM CST - 1-3-2 09/04 vs. Loudoun United 7:00PM CST - 09/11 @ Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC 8:00PM CST - MATCH INFO 09/18 vs. Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC 7:00PM CST - Saturday, June 12 09/22 @ New Mexico United 8:00PM CST - H-E-B Park 09/25 vs. -

The FA Disciplinary Regulations 2019/2020

TTHHEE FFAA DDIISSCCIIPPLLIINNAARRYY RREEGGUULLAATTIIOONNSS 2019/2020 Version: 1.0 CONTENTS PREFACE REGULATION CHANGES – NOTE TO PARTICIPANTS PARTS GENERAL PROVISIONS NON-FAST TRACK REGULATIONS APPEALS - NON-FAST TRACK ON-FIELD REGULATIONS FAST TRACK REGULATIONS INTERIM SUSPENSION ORDER REGULATIONS APPENDICES REGULATION CHANGES – NOTE TO PARTICIPANTS Participants should be aware that any of The Association’s Regulations may be amended during the season following publication of The FA Handbook. Reference should be made to The FA’s website, located at www.TheFA.com, for updated versions of the Regulations. GENERAL PROVISIONS SECTION ONE: ALL PANELS SECTION TWO: REGULATORY COMMISSIONS GENERAL PROVISIONS 1 These General Provisions are split into two parts: 1.1 The provisions in Section One shall apply to Inquiries, Commissions of Inquiry, Regulatory Commissions, Disciplinary Commissions, Appeal Boards and Safeguarding Review Panels. 1.2 The provisions in Section Two shall apply to Regulatory Commissions and, where stated in paragraph 27, Disciplinary Commissions. SECTION ONE: ALL PANELS SCOPE 2 This Section One shall apply to Inquiries, Commissions of Inquiry, Regulatory Commissions, Disciplinary Commissions, Appeal Boards and Safeguarding Review Panels. 3 In relation to proceedings before a Disciplinary Commission, references in this Section One to The Association shall be taken to mean the relevant Affiliated Association. GENERAL 4 The bodies subject to these General Provisions are not courts of law and are disciplinary, rather than arbitral, bodies. In the interests of achieving a just and fair result, procedural and technical considerations must take second place to the paramount object of being just and fair to all parties. 5 All parties involved in proceedings subject to these General Provisions shall act in a spirit of co-operation to ensure such proceedings are conducted expeditiously, fairly and appropriately, having regard to their sporting context. -

EFL League One and League Two Draft Salary Cap Rules Points for Consideration Introduction

EFL League One and League Two draft Salary Cap rules Points for consideration Introduction The PFA has long supported the principles of cost control measures in their objective of ensuring the financial sustainability of EFL clubs. We recognise the need for a well defined and implemented set of regulations and we believe further consideration is required to meet the objectives of all stakeholders before proceeding with the implementation of the EFL’s draft Salary Cap rules for Leagues One and Two Following receipt by the PFA of the the years, the PFA has also contributed in assisting We have asked the independent Sports Business EFL’s draft Salary Cap rules (the the financial position of many EFL clubs through Group at Deloitte (who most recently assisted ‘draft rules’) dated 29th July 2020 for the provision of financial support. We want to see us with the financial review exercise as part of League One and League Two clubs, English football operate in a sustainable manner the response to Covid-19) to provide us with the the PFA have reviewed the draft – this is to the benefit of our Members, but also to principles of cost control measures to inform the rules and present this document for consideration that of all stakeholders across the game. content of this document, based on their experience and discussion. We understand that a vote is to of assisting multiple stakeholders in the development take place on Friday 7th August, where the draft We are not opposed to the principles of cost of cost control regulations across the sports industry. -

The Relationship Between Team Ability and Home Advantage in the English Football League System

The relationship between team ability and home advantage in the English football league system RAMCHANDANI, Girish <http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8650-9382>, MILLAR, Robbie and WILSON, Darryl Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/28515/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RAMCHANDANI, Girish, MILLAR, Robbie and WILSON, Darryl (2021). The relationship between team ability and home advantage in the English football league system. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 51 (3), 354-361. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Main Article Ger J Exerc Sport Res Girish Ramchandani · Robbie Millar · Darryl Wilson https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-021-00721-x Academy of Sport and Physical Activity, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK Received: 9 July 2020 Accepted: 16 April 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 The relationship between team ability and home advantage in the English football league system Introduction for men’s and women’s competition. Te 1995). In other words, performance has HA found for football in the Pollard two components, namely: quality and Te phenomenon of home advantage et al. (2017a) study was somewhat below HA. If every team in a league enjoys the (HA), where home teams in sports com- its historical position relative to other same level of HA, then performance is petitions win over half of the games sports. Within football, the existence dependent on quality alone; however, played under a balanced home and away of HA across national domestic leagues if some teams have superior HA then schedule (Courneya & Carron, 1992), worldwide was illustrated by Pollard their performance will be naturally en- has received widespread attention from and Gomez (2014a). -

AFC Wimbledon Season Cards Terms & Conditions 2021/22 Season

AFC Wimbledon Season Cards Terms & Conditions 2021/22 Season These terms and conditions (“Conditions”) and any documents referred to in these Conditions apply to all purchases of Season Cards from AFC Wimbledon Limited (“AFCW”). By purchasing a Season Card from AFCW, you acknowledge and agree that you shall be bound by these Conditions. 1. Definitions and Interpretation 1.1 In these Conditions, the following terms shall have the following meanings: “Agreement” means these Conditions, the Confirmation, the Ticket Terms and Conditions, the Terms and conditions of entry and any other documents referred to herein; “Conditions” means these terms and conditions; “Credit Facility” means any credit facility provided to you by way of a regulated loan by AFCW, or any third partner selected by AFCW, that is used by you in order to fund the payment of the price of your Season Card. “EFL” means the Football League Limited; “Ground” means the stadium in which the first team play their competitive matches; “Ground Regulations” means AFCW’s ground regulations as issued by AFCW from time to time that set out the terms and conditions upon which spectators are granted entry to the Ground, a copy of which is available upon request; “Guest” means a person who has been granted use of your Season Card by you, in respect of one or more Matches, being someone who would be eligible to purchase that Season Card himself/herself under these Conditions; “League” means the league (currently operated by the EFL) that AFCWC competes in during the Season; “Match” means -

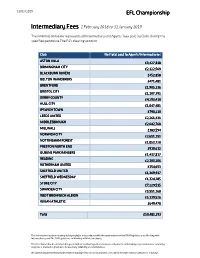

EFL Intermediaries Fees

31/03/2019 EFL Championship Intermediary Fees 1 February 2018 to 31 January 2019 The information below represents all Intermediary and Agents' fees paid by Clubs during the specified period via The FA's clearing account Club Net total paid to Agents/Intermediaries ASTON VILLA £££3,427,818£3,427,818 BIRMINGHAM CITY £2,122,569 BLACKBURN ROVERS £452,858 BOLTON WANDERERS £471,481 BRENTFORD £1,905,236 BRISTOL CITY £1,107,391 DERBY COUNTY £4,293,410 HULL CITY £1,047,481 IPSWICH TOWN £790,210 LEEDS UNITED £2,261,431 MIDDLESBROUGH £2,642,768 MILLWALL £383,594 NORWICH CITY £2,651,151 NOTTINGHAM FOREST £1,053,720 PRESTON NORTH END £910,612 QUEENS PARK RANGERS £1,437,817 READING £2,103,206 ROTHERHAM UNITED £154,653 SHEFFIELD UNITED £1,369,917 SHEFFIELD WEDNESDAY £1,324,285 STOKE CITY £7,229,515 SWANSEA CITY £5,551,168 WEST BROMWICH ALBION £5,139,526 WIGAN ATHLETIC £649,478 Total £££50,481,293 This information has been made publicly available in accordance with the requirements of the FIFA Regulations on Working with Intermediaries and The FA Regulations on Working with Intermediaries. The information has been included in good faith for football regulatory purposes only and no undertaking, representation or warranty (express or implied) is given as to its accuracy, reliability or completeness. We cannot guarantee that any information displayed has not been changed or modified through malicious attacks or “hacking”. 31/03/2019 EFL League One Intermediary Fees 1 February 2018 to 31 January 2019 The information below represents all Intermediary and Agents' -

Oliver Myles Events Calendar 2020

Oliver Myles Events Calendar 2020 www.olivermyles.co.uk January 2020 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 1 2 3 4 5 New Year Meeting Cheltenham Racecourse 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Cirque Du Soleil Royal Albert Hall 12 Jan - 16 Feb 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Legends of Rugby Dinner Grosvenor House Hotel, London 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Burns Night on the Royal "Happy New Year! We hope you have a fantastic Yacht Britannia 2020. We're here to help you with your bespoke An Oliver Myles Events Exclusive events, corporate hospitality and ticketing needs - 27 28 29 30 31 offering advice you can trust and enviable industry knowledge, experience and contacts." -The Oliver Myles Events team 01442 768110 www.olivermyles.co.uk [email protected] February 2020 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 1 2 Six Nations: Six Nations: Wales v Italy France v Ireland v England Scotland 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Six Nations: Six Nations: Ireland v Wales France v Italy Scotland v Eng S uper Saturday Newbury Races 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 A Viennese A Viennese A Viennese Ball Experience Ball Experience Ball Experience An Oliver Myles Events Exclusive Ascot Chase Experience Raceday Event of the Month: A Viennese Whirl 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Stay at the 5-Star Hotel Bristol in Vienna and experience Six Nations Six Nations Wales v France England v a traditional Viennese Ball at the Hofburg Palace. This Italy v Scotland Ireland K empton Park romantic three day experience, over Valentine's Day, also Chase includes a private waltzing lesson and a horse drawn 24 25 26 27 28 29 carriage ride. -

EFL League One 2021/22

EFL League One 2021/22 John Aitken & Alien Copeland EFL League One 2021/22 Contents Accrington Stanley ..................................................................................................... 4 AFC Wimbledon……………………………………………………………………………..7 Bolton Wanderers .................................................................................................... 10 Burton Albion……………………………………………………………………………….14 Cambridge United ……………………………………………………………………… 19 Charlton Athletic.…………………………………………………………………………. 23 Cheltenham Town ……………………………………………………………………… 29 Crewe Alexandria ………………………………………………………………………… 32 Doncaster Rovers………………………………………………………………………….37 Fleetwood Town…………………………………………………………………………....40 Gillingham…………………………………………………………………………………..45 Ipswich Town……………………………………………………………………………… 49 Lincoln City ……………………………………………………………………………….. 53 Milton Keynes Dons ……………………………………………………………………… 58 Morecambe ………..………………………………………………………………….…. 62 Oxford United………………………………………………………………………………66 Plymouth Argyle ………………………………………………………………………….. 71 Portsmouth………………………………………………………………………………….75 Rotherham United …………………………………………………………………………80 Sheffield Wednesday …………………………………………………………………… 83 Shrewsbury Town……………………………………………………………………….... 87 Sunderland………………………………………………………………………………… 94 Wigan Athletic …………………………………………………………………………… 96 Wycombe Wanderers ………………………………………………………………… 99 1 1. EFL Groundhopper book 2019/20 League One Page 2 EFL League One 2021/22 Guide to League One teams for 2019-20 season in this part of the book I have outlined their history old