FEDERALISM : a CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS Author(S): S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T'the Phoenix Has Now Risen from Its Ashes

THE ACADEMY & THE HUMANITIES IN 19691 » Graeme DAVison ‘The Phoenix has now risen from its ashes, Seventy-one year old Hancock and a lovelier bird and — what matters more — a seventy-five year old Menzies were near- Tlivelier one’, the inaugural president of the contemporaries, having both arrived at the Australian Academy of the Humanities, Sir University of Melbourne as scholarship boys Keith Hancock, wrote exultantly to its political in the years around World War One. Each patron, Sir Robert Menzies, at the end of man, in his way, had been imbued with ideals September 1969. ‘We have not only a new name of academic and public service through their but a new infusion of creative vigour’.2 Since studies under the university’s influential the foundation of the Australian Humanities Professor of Law, Harrison Moore.3 Both were Research Council (AHRC) in 1955, its founders products of the liberal imperialism of their era, had anticipated its transformation, in due Hancock becoming the pre-eminent historian course, into an Academy of Letters or, as it of the British Empire, and Menzies one of 'THE PHOENIX HAS NOW RISEN FROM ITS ASHES, A LOVELIER BIRD AND — WHat MattERS MORe — A LIVELIER ONE' — sIR KEITH HANCOCK IN A LEttER TO SIR ROBERT MENZIES, 1969. turned out, an Academy of the Humanities. its most devoted political servants. While The plumage of the new bird, with its royal Hancock had won academic laurels in Oxford charter and crest, was certainly more glorious and London, returning to his homeland only than that of the old AHRC, but the bird itself towards the end of his career, Menzies had was remarkably like the old one. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

Professor Carolyn Evans, Vice Chancellor and President, Griffith

Professor Carolyn Evans, Vice Chancellor and President, Griffith University Professor Carolyn Evans commenced her appointment as Vice Chancellor and President of Griffith University in February 2019, leading one of Australia’s fastest-growing and most progressive tertiary institutions, ranked in the top 2% of universities worldwide. Prior to joining Griffith, Professor Evans was Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Graduate and International) and Deputy Provost (2017-2018) at the University of Melbourne, and Dean and Harrison Moore Professor of Law, University of Melbourne Law School (2011-2017). Professor Evans has degrees in Arts and Law from the University of Melbourne and a doctorate from Oxford University, where she studied as a Rhodes Scholar and held a stipendiary lectureship for two years. In 2010, Carolyn was awarded a Fulbright Senior Scholarship to allow her to travel as a Visiting Fellow to American and Emory Universities to examine questions of comparative religious freedom. She has also taught in the human rights summer school at European University Institute. Throughout her career, Carolyn has promoted the importance of universities combining excellence in teaching and research with a commitment to social justice and inclusion. Carolyn is the author of Legal Protection of Religious Freedom in Australia (Federation Press 2012), Religious Freedom under the European Court of Human Rights (OUP 2001) and co-author of Australian Bills of Rights: The Law of the Victorian Charter and the ACT Human Rights Act (LexisNexis 2008). She is co-editor of Religion and International Law (1999, Kluwer); Mixed Blessings: Laws, Religions and Women's Rights in the Asia-Pacific Region (2006 Martinus Nijhoff) and Law and Religion in Historical and Theoretical Perspective (CUP 2008). -

The Constitutional Conventions and Constitutional Change: Making Sense of Multiple Intentions

Harry Hobbs and Andrew Trotter* THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE: MAKING SENSE OF MULTIPLE INTENTIONS ABSTRACT The delegates to the 1890s Constitutional Conventions were well aware that the amendment mechanism is the ‘most important part of a Cons titution’, for on it ‘depends the question as to whether the state shall develop with peaceful continuity or shall suffer alternations of stagnation, retrogression, and revolution’.1 However, with only 8 of 44 proposed amendments passed in the 116 years since Federation, many commen tators have questioned whether the compromises struck by the delegates are working as intended, and others have offered proposals to amend the amending provision. This paper adds to this literature by examining in detail the evolution of s 128 of the Constitution — both during the drafting and beyond. This analysis illustrates that s 128 is caught between three competing ideologies: representative and respons ible government, popular democracy, and federalism. Understanding these multiple intentions and the delicate compromises struck by the delegates reveals the origins of s 128, facilitates a broader understanding of colonial politics and federation history, and is relevant to understanding the history of referenda as well as considerations for the section’s reform. I INTRODUCTION ver the last several years, three major issues confronting Australia’s public law framework and a fourth significant issue concerning Australia’s commitment Oto liberalism and equality have been debated, but at an institutional level progress in all four has been blocked. The constitutionality of federal grants to local government remains unresolved, momentum for Indigenous recognition in the Constitution ebbs and flows, and the prospects for marriage equality and an * Harry Hobbs is a PhD candidate at the University of New South Wales Faculty of Law, Lionel Murphy postgraduate scholar, and recipient of the Sir Anthony Mason PhD Award in Public Law. -

Menzies and Howard on Themselves: Liberal Memoir, Memory and Myth Making

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2018 Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making Zachary Gorman University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gregory C. Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gorman, Zachary and Melleuish, Gregory C., "Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making" (2018). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 3442. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/3442 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making Abstract This article compares the memoirs of Sir Robert Menzies and John Howard, as well as Howard's book on Menzies, examining what these works by the two most successful Liberal prime ministers indicate about the evolution of the Liberal Party's liberalism. Howard's memoirs are far more 'political', candid and ideologically engaged than those of Menzies. Howard acknowledges that politics is about political power and winning it, while Menzies was more concerned with the political leader as statesman. Howard's works can be viewed as a continuation of the 'history wars'. He wishes to create a Liberal tradition to match that of the Labor Party. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Gorman, Z. -

Working Beyond Government: Evaluation of Ausaid's

Working Beyond Government EVALUATION OF AUSAID’S ENGAGEMENT WITH CIVIL SOCIETY IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES ODE EVALUATIONS & REVIEWS MARCH 2012 Working Beyond Government EVALUATION OF AUSAID’S ENGAGEMENT WITH CIVIL SOCIETY IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Jude Howell I Jo Hall © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca ISBN: 978-0-9872584-1-0 Published by the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Canberra, March 2012. This document is online at www.ode.ausaid.gov.au/publications Disclaimer: The views in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Office of Development Effectiveness. For further information, contact: Office of Development Effectiveness AusAID GPO Box 887 Canberra ACT 2601 Phone (02) 6206 4000 Facsimile (02) 6206 4880 Internet www.ausaid.gov.au www.ode.ausaid.gov.au Cover image: Bike Club members about to leave Wan Smolbag’s Youth Centre on a field trip to Mele village in Vanuatu. The field trip included a tour of the village and ended in races at the local sports ground. Photo credit: Dianne Hambrook, 2010 Office of Development Effectiveness The Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) at AusAID builds stronger evidence for more effective aid. -

Potter V. Minahan: Chinese Australians, the Law and Belonging in White Australia

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2018 Potter v. Minahan: Chinese Australians, the law and belonging in White Australia Kate Bagnall University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bagnall, Kate, "Potter v. Minahan: Chinese Australians, the law and belonging in White Australia" (2018). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 3628. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/3628 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Potter v. Minahan: Chinese Australians, the law and belonging in White Australia Abstract This article tells the story of James Minahan, the Melbourne-born son of a Chinese father and a white Australian mother who was arrested as a prohibited immigrant under the Immigration Restriction Act in 1908. Minahan had been taken to China by his father as a five-year-old boy in 1882 and failed the Dictation Test on his return to Australia 26 years later. After Minahan defeated the charge in the lower courts, the Commonwealth appealed to the High Court - an appeal they lost on the grounds that, despite his years overseas, Minahan had remained a member of the Australian community. Although the case is well known in historical and legal scholarship on Australian immigration and citizenship, existing work has focused primarily on the High Court judgements. -

The Constitution Makers

Papers on Parliament No. 30 November 1997 The Constitution Makers _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1997 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Editors of this issue: Kathleen Dermody and Kay Walsh. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3078 ISSN 1031–976X Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Cover illustration: The federal badge, Town and Country Journal, 28 May 1898, p. 14. Contents 1. Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies 1 The Hon. John Bannon 2. A Federal Commonwealth, an Australian Citizenship 19 Professor Stuart Macintyre 3. The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention 33 Professor Geoffrey Bolton 4. Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—the Senate’s First Republican 49 Dr Mark McKenna 5. The High Court and the Founders: an Unfaithful Servant 63 Professor Greg Craven 6. The 1897 Federal Convention Election: a Success or Failure? 93 Dr Kathleen Dermody 7. Federation Through the Eyes of a South Australian Model Parliament 121 Derek Drinkwater iii Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies* John Bannon s we approach the centenary of the establishment of our nation a number of fundamental Aquestions, not the least of which is whether we should become a republic, are under active debate. But after nearly one hundred years of experience there are some who believe that the most important question is whether our federal system is working and what changes if any should be made to it. -

Download PDF Read More

ALRC 2009–10 R E P O R T 113 ANNUAL REPORT Requests and inquiries regarding this report should be addressed to: The Executive Director Australian Law Reform Commission GPO Box 3708 Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: (02) 8238 6333 Fax: (02) 8238 6363 Email: [email protected] This report is also accessible online at: www.alrc.gov.au ISBN 978-0-9807194-3-7 Print Post Approval Number: PP255003/02228 © Commonwealth of Australia 2010 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in whole or part, subject to acknowledgement of the source, for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all other rights are reserved. Requests for further authorisation should be directed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch, Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600. Alternatively, an online request form is available at <www. ag.gov.au/cca>. Printed by Union Offset Printers ii Professor David Weisbrot AM ProfessorProfessor Rosalind David WeisbrotF Croucher AM PresPresidentident President The Honourable Robert McClelland MP The Honourable Philip Ruddock MP TheAttorney-General Honourable Philip Ruddock MP Attorney-General Attorney-GeneralParliament House Parliament House Parliament House CanberraCanberra ACT ACT 2600 2600 Canberra ACT 2600 2219 OctoberSeptember 2007 2010 19 October 2007 Dear Attorney-General Dear Attorney-General Dear Attorney-General On behalf of the members of the Australian Law Reform Commission, I am pleased to present the On behalf of the members of the Australian Law Reform Commission, I am pleased to present the Annual Report of the Australian Law Reform Commission for the period 1 July 2006 to 30 June Annual Report of the Australian Law Reform Commission for the period 1 July 2006 to 30 June 2007. -

Scangate Document

Vision for Commonwealth’s own police service belonged to Australia’s first publ ic servant Anthony Ralph is a former member of Historical writings show that the AFP and former senior lecturer in although the timing for the force’s establishment was incorrect and police studies at Deakin University. Hughes’ use of the force for political This edited article was extracted from purposes contemptible, the need for his doctoral research into the the Commonwealth’s own investigatory body was arguably legislative and legal influences on the sound. development of federal policing in As La Nauz reveals, responsibility Australia. for drafting legislation and providing the fledgling federal government with legal advice fell upon Australia’s first federal public servant, Sir Robert Garran.1 Anthony Ralph Sir John Latham, in writing an obituary for Garran detailing the work of this brilliant legal mind, stated that statutes “enacted at this time provided Despite the long held and the framework within which the popular belief that the first Commonwealth could come fully to federal policing organisation in life. Garran bore the burden of preparing this legislation”.2 In a tribute Australia was established from to Garran, Hughes was to state that a knee-jerk political reaction by “the best way to govern Australia was to have Sir Robert Garran at his elbow William Morris Hughes in with a fountain pen and a blank sheet 1917, the idea for its formation of paper”. 3 Garran was a man of actually belonged to another. vision utilising the law not only as a form of social control but also as a tool While history accurately records to establish and maintain the that Hughes established the first constitutional framework of an Commonwealth Police Force after an independent federated nation. -

The People and the Constitution

THE PEOPLE AND THE CONSTITUTION THE HON JUSTICE PATRICK KEANE AC* It is a great honour to have been asked to give this year’s Lucinda Lecture. It would be churlish of me, as a Queenslander, to observe that at the time that the great work was done on the ship after which this lecture is named, she was owned and crewed by Queenslanders. It would be churlish, but we Queenslanders acknowledge no equals when it comes to our capacity for churlishness. However, quite apart from being churlish, it would be wrong on this occasion to make special claims for the contributions of particular colonies because the work which was done on the Lucinda was done by individuals who made themselves the first Australians. By their efforts, they ensured that we, too, would have that privilege. Their work stands as an enduring reminder that, just as those individuals from their separate colonies combined their talents to forge a nation, so today’s Australians can work together to make a more just nation with confidence that their efforts will not be in vain. I THE PEOPLE IN POLITICS It was only in the latter half of the 18th century that the idea of the people as a source of sovereign authority emerged as a central element of political discourse in the west. And once it emerged it almost immediately became the focus of fierce polemic. Edmund Burke, in his reaction to the French Revolution, spoke of the aristocracy and higher clergy, and those who deferred to them, as the only true ‘people’ of France. -

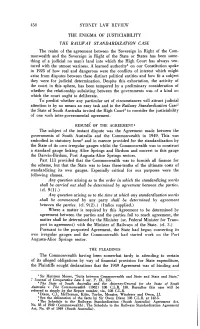

THE RAILWAY STANDARDIZATION CASE Any Question

SYDNEY LAW- REVIEW THE ENIGMA OF JUSTICIABILITY THE RAILWAY STANDARDIZATION CASE The realm of the agreement between the Sovereign in Right of the Com- monwealth and the Sovereign in Right of the State or States has been some- thing of a judicial no man's land into which the High Court has always ven- tured with the utmost wariness. A learned authority1 on our Constitution spoke in 1925 of how real and dangerous were the conflicts of interest which might arise from disputes between these distinct political entities and how fit a subject they were for judicial determination. Despite this exhortation, the activity of the court in this sphere, has been tempered by a preliminary consideration of whether the relationship subsisting between the governments was of a kind on which the court ought to deliberate. To predict whether any particular set of circumstances will attract judicial attention is by no means an easy task and in the Railway Standardization Case' the State of South Australia invited the High Court3 to consider the justiciability of one such inter-governmental agreement. RESUME/ OF THE AGREEMENT4 The subject of the instant dispute was the Agreement made between the governments of South Australia and the Commonwealth in 1949. Th'is was embodied in statutory form5 and in essence provided for the standardization by the State of its own irregular gauges whilst the Commonwealth was to construct a standard gauge linking Alice Springs and Birdum and convert to this gauge the Darwin-Birdum, Port Augusta-Alice Springs sectors. Part 111 provided that the Commonwealth was to furnish all finance for the scheme, but that the State was to bear three-tenths of the ultimate costs of standardizing its own gauges.