Reflections on Korean History and Its Impacts on the US-North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CKS NEWSLETTER Fall 2008

CKS NEWSLETTER Fall 2008 Center for Korean Studies, University of California, Berkeley Message from the Chair Dear Friends of CKS, Colleagues and Students: As we look forward to the thirtieth anniversary of the Center for Korean Studies (CKS) in 2009, we welcome our friends, colleagues, visiting scholars, and students to a year of new programs that we have scheduled for 2008–2009. In addition to continuing with the regular programs of past years, we began this year with the conference “Places at the Table,” an in-depth exploration of Asian women artists with a strong focus on Korean art. We presented a conference on “Reunification: Building Permanent Peace in Korea” (October 10) and a screening of the documentary film “Koryo Saram” (October 24). “Strong Voices,” a forum on Korean and American women poets, is scheduled for April 1–5, 2009. We are in the early planning stages for a dialogue on Korean poetry between Professor Robert Hass of UC Berkeley and Professor David McCann of Harvard, in conjunction with performances of Korean pansori and gayageum (September 2009). Providing that funding is approved by the Korea Foundation, an international conference on Korean Peninsula security issues (organized by Professor Hong Yung Lee) is also planned for next year. The list of colloquium speakers, conferences, seminars, and special events is now available on the CKS website. (See page 2 for the fall and spring schedule.) We welcome novelist Kyung Ran Jo as our third Daesan Foundation Writer-in-Residence. Ms Jo, whose novels have won many awards, will give lectures and share her writing with the campus community through December of this year. -

Park, Albert-CV 2020.Pdf

Albert L. Park Department of History Claremont McKenna College 850 Columbia Avenue Claremont, CA 91711-6420 909-560-2676 [email protected] Academic Employment Bank of America Associate Professor of Pacific Basin Studies, May 2018 to Present Associate Professor, Department of History, Claremont McKenna College, May 2014 to May 2018 Co-Principal Investigator, EnviroLab Asia at the Claremont Colleges, March 2015 to Present Co-Founder and Co-Editor of Environments of East Asia—a multi-disciplinary book series on environmental issues in East Asia that is published by Cornell University Press, November 2019 to Present Extended Faculty, Department of History, Claremont Graduate University, 2010 to Present Assistant Professor, Department of History, Claremont McKenna College, July 2007 to April 2014 Luce Visiting Instructor, East Asian Studies Program, Oberlin College, July 2006-June 2007 Education University of Chicago, Department of History, Chicago, IL Ph.D. History, August 2007 Dissertation Title: “Visions of the Nation: Religion and Ideology in 1920s and 1930s Rural Korea” Dissertation Committee: Bruce Cumings (Chair), James Ketelaar, Tetsuo Najita, William Sewell Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea Korean Language Institute, June 1998-June 1999 Columbia University, Department of History, New York, NY M.A. History, October 1998 Park, 2 Keio University, Tokyo, Japan Japanese Language Program, September 1996-February 1997 Northwestern University, Evanston, IL B.A. History, May 1996, Departmental Honors Publications --Authored Books Building -

With the Inauguration of the Bush Administration in 2001, South Korea

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES LOOKING BACK AND LOOKING FORWARD: NORTH KOREA, NORTHEAST ASIA AND THE ROK-U.S. ALLIANCE Dr. Hyeong Jung Park CNAPS Korea Fellow, 2006-2007 Senior Research Fellow, Korea Institute for National Unification December 2007 The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Tel: 202-797-6000 Fax: 202-797-6004 www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. ROK-U.S. dissonances in 2001-2006 2.1. How to understand the surge of anti-American sentiment in 2002-2004 2.2. North Korea policy 2.3. Redefinition of the ROK-U.S. military alliance 2.4. South Korea’s relations with China and Japan 3. Exploration for a ROK-U.S. Joint Strategy 3.1. Signs of a new beginning 3.2. Challenges for the United States Three-track strategy The crisis of the San Francisco system and the crisis of ROK-U.S. relations in 2001-2006 Establishing a convergent security regime in Northeast Asia 3.3. Challenges for South Korea Starting points for South Korea’s North Korea policy after the presidential election in December 2007 Elements of South Korea’s strategic thinking in previous years Policy challenges for the new president of South Korea 4. Summary and policy recommendations 2 Hyeong Jung Park North Korea, Northeast Asia, and the ROK-U.S. Alliance CNAPS Visiting Fellow Working Paper 1. Introduction1 Following the inauguration of the Bush administration in 2001, South Korea and the United States entered into a period of dissonance and even mutual repugnance. -

From De Jure to De Facto: the Armistice Treaty and Redefining * the Role of the United Nations in the Korean Conflict

International Studies Review Vol. 2 No. 1. _(Jun.e 1998): I 13~{26 113 From De Jure to De Facto: The Armistice Treaty and Redefining * the Role of the United Nations in the Korean Conflict )UNG-HOON LEE G'radu11te School of1ntem11tional Studies, Yonsei University North Korea has kng tried to undennine the Armistice Treaty of1953 in order to replace it with a comprehensive peace treaty with the United States. With North Korea cksing its territory to members ofthe Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) in 1995, the debate over the practicability ofthe Military Armistice Treaty has been rekindkd in recent years. In a broader sense, at issue is the effectiveness of the United Nations Command in continuing to maintain peace on the Korean peninsuw. How functional has the armistice treaty been in enforcing its ruks? In what ways does the annistice treaty affect the inter-Korean relationship? To what extent would a U.S.-North Korea peace treaty compromise the positions of the United Nations Command and the U.S. armed forces in South Korea? Keeping in mind these and other questions, this article examines first, the chal lenges facing the UN-sponsored armistice apparatus, and second, how the involved parties -- South Korea in particular -- may cope with these challenges to ensure pennanent security in Korea. This artick sug gests that South Korea should propose to revive the principles raised in the Geneva Conference of 1954, especia/{y concerning the need for the recognition of the United Nations ' authority and competence to deal with the Komm affairs. With the Cold W{zr ended, the Conference stands a far better chance to survive and perhaps to resolve the Korean question once and for all. -

The Korean War and Asian/American Culture

AMST 238-01: Forgotten/Remembered: The Korean War and Asian/American Culture Professor Terry K. Park, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Class: Tuesday/Friday, 9:50am – 11am, Founders Hall 126 Office: Pendleton East 123A Office Hours: Tuesdays 12-1pm & Fridays 1-2pm, and by appointment Mailbox: American Studies Program Office, Founders Hall Course Description. The 1950-53 Korean War is often called the United States's "forgotten war." Despite this designation, the war's immense devastation, its transformation of the US's presence in the Asian-Pacific region, and its racialized and gendered effects have produced a number of texts that remember a war without end. This course offers a transnational cultural history of the Korean War, unspooling its multiple threads in order to come to terms with the way it shaped--and continues to shape--the US's sense of its self, its place in the world, and the heartland of Korean America. Thus, rather than reinforce official ideologies of the Korean War as a distant and discrete "police action," students will consider the war as a series of unwieldy discourses--including containment, de/militarization, desegregation, brainwashing, debt, impersonation, red-baiting, and "han"--whose ghostly legacies whisper inconvenient truths about the triangulated relations among, and complexities within, US empire, the US nation-state, and Korean America. Three sets of questions will guide the course: • How did the Korean War (re)shape US empire? How does it continue to shape the US presence in Korea and the broader Asian-Pacific region? • How did the Korean War shape US national culture, or meanings of “America”? In turn, how does the US “remember,” or “forget,” the Korean War? • How did the Korean War shape the Korean diaspora? In turn, how does the Korean diaspora “remember” the Korean War? How do these rememberings contest official narratives of the Korean War, Korean America, and US empire? How do they imagine otherwise new relations, practices, and modes of being? Required Texts. -

Humanity Interrogated: Empire, Nation, and the Political Subject in U.S. and UN-Controlled POW Camps of the Korean War, 1942-1960

Humanity Interrogated: Empire, Nation, and the Political Subject in U.S. and UN-controlled POW Camps of the Korean War, 1942-1960 by Monica Kim A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Penny M. Von Eschen, Chair Associate Professor Sarita See Associate Professor Scott Kurashige Associate Professor Henry Em, New York University Monica Kim 2011 For my parents Without whom, this never would have been written ii Acknowledgements It has been my incredible fortune that a vision shared also means a life shared. And much life has been shared in the fostering and development of this project, as it moved from idea to possibility to entirely unpredictable experiences in the field and in writing. My dissertation committee members have been involved with this project ever since the beginning. I am indebted not only to their commitment to and support of my ideas, but also to their own relationships with work, writing, and social justice. By their own examples, they have shown me how to ask the necessary, important questions to push my own scholarship constantly into a critical engagement with the world. Penny von Eschen has granted me perhaps one of the most important lessons in scholarship – to write history unflinchingly, with a clarity that comes from a deep commitment to articulating the everyday human struggles over power and history. A wise teacher and an invaluable friend, Penny has left an indelible imprint upon this work and my life, and I am excited about working together with her on projects beyond this dissertation. -

The Two Koreas

1 History 292/392 The Two Koreas Winter 2009 Mon 1:15–3:05pm Classroom 260–001 Professor: Yumi Moon Building 200 (Lane/History Corner), Office 228 Phone: (650) 723–2992 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Wed 1:00–3:00 pm., and by appointment Course Description The history of the two Koreas began in 1945, when the United States and Soviet Union agreed to divide the country along the 38th parallel and to occupy North and South separately. This division had a great impact on Korea’s decolonization process and resulted in the outbreak of the Korean War. The war quickly developed into the first international war after World War II and completed the regime of the Cold War in East Asia. After the war the two Koreas took dramatically different historical paths, and the nation’s division is now comprehensive and internalized among the residents of the two Koreas. This system of the two Koreas survived the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s but is now entering a crucial historical stage toward its fundamental transformation or even its dissolution. This course will examine major themes and scholarly works to understand the rise of the two Koreas and their subsequent historical developments. Themes will include the historical and ideological origins of the division, the impact of Japanese colonial rule, the Korean War, the ideas of key North and South Korean leaders, and the consolidation of the two different states into North and South after the Korean War. The structure of this colloquium will be divided into three chronological periods: the colonial origins of the nation’s division (1910–45), the Korean War and the involvements of international powers (1945–53), and the consolidation of the two different states in the aftermath of the war (1953–). -

Families of Eight Wrongfully Executed South Korean Political Prisoners Awarded Record Compensation

Volume 5 | Issue 10 | Article ID 2534 | Oct 01, 2007 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Families of Eight Wrongfully Executed South Korean Political Prisoners Awarded Record Compensation. The People's Revolutionary Party 8 Hankyoreh, Bruce Cumings Families of Eight Wrongfully Executed South Korean Political Prisoners Awarded Record Compensation. The People's Revolutionary Party 8 Bruce Cumings and Hankyoreh Introduction The large monetary awards to the family members of eight men executed in 1974 as Families of the so-called People’s members of the “People’s Revolutionary Party” Revolutionary Party weep upon hearing the have no precedent, and mark another milestone Supreme Court's ruling at Seoul Central in South Korea’s remarkable record of District Court on Aug. 20. Lee Jong-geun historical reckoning and reconciliation. The photo twin pillars of this are the reconciliation with Few foreigners recognize the degree to which, North Korea ongoing since Kim Dae Jung was not even a decade ago, South Korea needed not elected president, and the 1995 trials of former just to be reconciled to itself, but to be unified presidents Chun Doo Hwan and Roh Tae Woo as a country. In many ways the peninsula had for treason in carrying out their serial coup three different parts—the North, the South, and d’etat in 1979-80, which involved the bloody the remnants of a strong left wing in the suppression of the Kwangju Rebellion. (Chun southwest and southeast. Kwangju, a major city was sentenced to death and Roh to life in in the southwest, had been rebellious since the prison, but President Kim pardoned both of Tonghak peasant masses marched on Seoul in them so they could sit fidgeting on the podium 1894 and helped to touch off the Sino-Japanese while he was inaugurated in February 1998). -

Cumings, Bruce. Korea's Place in the Sun, a Modern History. New York: W.W

Document generated on 10/01/2021 4:20 a.m. Journal of Conflict Studies Cumings, Bruce. Korea's Place in the Sun, A Modern History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997. Michael Sheng Volume 20, Number 2, Fall 2000 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs20_2br09 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Sheng, M. (2000). Review of [Cumings, Bruce. Korea's Place in the Sun, A Modern History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997.] Journal of Conflict Studies, 20(2), 162–163. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 2000 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Cumings, Bruce. Korea's Place in the Sun, A Modern History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997. There are many East Asian programs on university campuses all over the United States, Canada and Western Europe; only a handful of them, however, include Korea studies. Korea is also conspicuously missing in many textbooks on East Asian history or civilizations, as if the region includes only China and Japan. In the vast corpus of literature on the Korean War, the emphases are likely on the geo-political games, the strategic interests and the military operations of the major powers, namely the United States, the Soviet Union and China; Korea hardly mattered. -

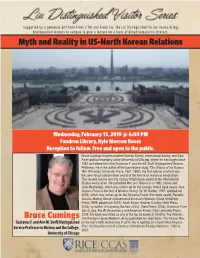

February 13, 2019 @ 4:00 PM Fondren Library, Kyle Morrow Room Reception to Follow

Supported by a generous gift from Frank (‘78) and Cindy Liu, the Liu Distinguished Visitor Series brings distinguished visitors to campus to give a lecture on a topic of broad humanistic interest. Myth and Reality in US-North Korean Relations Wednesday, February 13, 2019 @ 4:00 PM Fondren Library, Kyle Morrow Room Reception to follow. Free and open to the public. Bruce Cumings teaches modern Korean history, international history, and East Asian political economy at the University of Chicago, where he has taught since 1987 and where he is the Gustavus F. and Ann M. Swift Distinguished Service Professor. He is the author of the two-volume study, The Origins of the Korean War (Princeton University Press, 1981, 1990), the first volume of which won the John King Fairbank book award of the American Historical Association. The second volume won the Quincy Wright book award of the International Studies Association. He published War and Television in 1992 (Verso and Visal-Routledge), which was runner-up for the George Orwell book award. Also Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (W. W. Norton, 1997; updated ed. 2005), which was runner-up for the Kiriyama Pacific Rim book award; Parallax Visions: Making Sense of American-East Asian Relations (Duke University Press, 1999; paperback 2002); North Korea: Another Country (New Press, 2003); co-author of Inventing the Axis of Evil (New Press, 2004); Dominion From Sea to Sea: Pacific Ascendancy and American Power (Yale University Press, 2009; this book was listed as one of the top 25 books of 2009 by The Atlantic). -

The Korean War: the Origins, Outbreak, and Aftermath

1 History 292/392 The Korean War: the Origins, Outbreak, and Aftermath Winter 2009 Mon 1:15–3:05pm Classroom 260–002 Professor: Yumi Moon Building 200 (Lane/History Corner), Office 228 Phone: (650) 723–2992 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Thursday 1:00–3:00 pm., and by appointment Course Description The history of two Koreas began in 1945, when the United States and Soviet Union agreed to divide the country along the 38th parallel and to occupy North and South separately. This division had a great impact on Korea’s decolonization process and resulted in the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. The war quickly developed into the first international war after World War II and completed the regime of the Cold War in East Asia. This course will examine major themes and scholarly works to understand why Korea’s decolonization led to the Korean War (1950-1953) and the confrontation of the two Koreas. Themes will include the local origins of the Korean War, the legacy of Japanese colonial rule, the internationalization of the Korean War, the motives of the United States, the Soviet Union, and China in the intervention to the war, ideas of key North and South Korean leaders, the role of the United Nations, the Cold War in East Asia, the consolidation of the two different states into North and South after the Korean War. Requirements Grading: Class Participation 50%; Presentation 10%, Two Response Papers 10%, In- Class Discussion 30% Final Research Paper 50%; Research Prospectus 5%, Progress Report 15%, Final Paper 30% Class Participation: This is a weekly two-hour seminar centered on discussion and debate. -

History 6393, "Empire, War, & Revolution" Bob Buzzanco Wednesday, 5:30-8:30 This Is a Readings Course in U.S. Fore

History 6393, "Empire, War, & Revolution" Bob Buzzanco Wednesday, 5:30-8:30 This is a readings course in U.S. foreign policy and international history, with an integrated emphasis on foreign and domestic sources and consequences of global behaviour and conflict. We will principally cover the 20th Century, with some brief background. Structure of the course: Each week, there will be a common reading for which everyone will be responsible . In addition to that, each week a certain number of students will read and report individually on books that are relevant to that week's topic. Assignments and Grading: In consultation with the professor, you will devise a reading list of 8 books, and write an essay at the end of the semester of about 12 pages in length on the major issues they raise about the history of US foreign policy. Learning Outcomes Students will have extensive knowledge about the history and historiographical debates relating to at least two regions of the world. All students graduating with a Ph.D. in History should be able to identify and analyze sufficient field-appropriate primary and secondary sources to write an acceptable dissertation. The History Department will produce Ph.D.s who will be accomplished teachers, researchers, and publishers at junior and senior level colleges and universities. Week 1: Introduction Common: William Appleman Williams, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy ; William Appleman Williams, "Charles Austin Beard: The Intellectual as Tory- Radical," in Henry Berger, ed, A William Appleman Williams Reader ; Roundtable on William Appleman Williams, Diplomatic History , Spring 2001; Buzzanco, "What Happened to the New Left .