California State University, Northridge Policy And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAME AFFILIATION MUSIC Arcos, Betto KPFK, Latin Music Expert

SANTA MONICA ARTS COMMISSION JURY POOL Updated 12/12/2014 NAME AFFILIATION MUSIC Arcos, Betto KPFK, latin music expert Barnes, Micah Bentley, Jason KCRW music program host; SM Downs, LeRoy KJAZ Eliel, Ruth Colburn Foundation Fernandez, Paul SM Music Center Fleischmann, Martin Music producer Franzen, Dale Performing arts producer Gallegos, Geoff "Double G" Jazz arranger/player/music director Gross, Allen Robert Artistic Director/Conductor, SM Symphony Guerrero, Tony Tony Guerrero Quartet Jain, Susan Pertel Producer, Chinese cultural expert Jones, O-Lan Composer, producer Karlin, Jan Levine, Iris Dr. Vox Femina Marshall, Anindo Director, Adaawe Maynard, Denise KJAZ Mosiman, Marnie singer Pourafar, Pirayeh Musician, teacher Pourmehdi, Houman Musician, teacher Cal Arts, Lian Ensemble Roden , Steve (also Visual Art) Visual artist/sound composer (Glow 2010) Scott, Patrick Artistic Director, Jacaranda music series, SM Smith, Dr. James SM College Sullivan, Cary Producer/Afro Funke Night Club PERFORMANCE ART Davidson, Lloyd Keegan & Lloyd Fabb, Rochelle Performance artist Fleck, John Performance Artist Froot, Dan Performance artist Gaitan, Maria Elena Performance Artist, Musician, Linguist, Educator Hartman, Lauren Crazy Space Kearns, Michael Writer/performer Keegan, Tom Keegan & Lloyd Kuida, Jennifer Great Leap Kuiland-Nazario, Marcus Curator, Performance artist Malpede, John LAPD Marcotte, Kendis Former Director, Virginia Avenue Project Miller, Tim Performance Artist/ Former Director Highways Palacios, Monica Performance artist Sakamoto, Michael Performance artist Werner, Nicole Dance, performance, theater Wong, Kristina SANTA MONICA ARTS COMMISSION JURY POOL Updated 12/12/2014 NAME AFFILIATION Woodbury, Heather Performance artist Zaloom, Paul Performance artist THEATER Abatemarco, Tony Skylight Theater Almos, Carolyn Loyola, Burglers of Hamm Almos, Matt Playwright, producer, Disney Corp. -

Media Contacts List

CONSOLIDATED MEDIA CONTACT LIST (updated 10/04/12) GENERAL AUDIENCE / SANTA MONICA MEDIA FOR SANTA MONICA EMPLOYEES Argonaut Big Blue Buzz Canyon News WaveLengths Daily Breeze e-Desk (employee intranet) KCRW-FM LAist COLLEGE & H.S. NEWSPAPERS LA Weekly Corsair Los Angeles Times CALIFORNIA SAMOHI The Malibu Times Malibu Surfside News L.A. AREA TV STATIONS The Observer Newspaper KABC KCAL Santa Monica Blue Pacific (formerly Santa KCBS KCOP Monica Bay Week) KMEX KNBC Santa Monica Daily Press KTLA KTTV Santa Monica Mirror KVEA KWHY Santa Monica Patch CNN KOCE Santa Monica Star KRCA KDOC Santa Monica Sun KSCI Surfsantamonica.com L.A. AREA RADIO STATIONS TARGETED AUDIENCE AP Broadcast CNN Radio Business Santa Monica KABC-AM KCRW La Opinion KFI KFWB L.A. Weekly KNX KPCC SOCAL.COM KPFK KRLA METRO NETWORK NEWS CITY OF SANTA MONICA OUTLETS Administration & Planning Services, CCS WIRE SERVICES Downtown Santa Monica, Inc. Associated Press Big Blue Bus News City News Service City Council Office Reuters America City Website Community Events Calendar UPI CityTV/Santa Monica Update Cultural Affairs OTHER / MEDIA Department Civil Engineering, Public Works American City and County Magazine Farmers Markets Governing Magazine Fire Department Los Angeles Business Journal Homeless Services, CCS Human Services Nation’s Cities Weekly Housing & Economic Development PM (Public Management Magazine) Office of Emergency Management Senders Communication Group Office of Pier Management Western City Magazine Office of Sustainability Rent Control News Resource Recovery & Recycling, Public Works SeaScape Street Department Maintenance, Public Works Sustainable Works 1 GENERAL AUDIENCE / SANTA MONICA MEDIA Argonaut Weekly--Thursday 5355 McConnell Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90066-7025 310/822-1629, FAX 310/823-0616 (news room/press releases) General FAX 310/822-2089 David Comden, Publisher, [email protected] Vince Echavaria, Editor, [email protected] Canyon News 9437 Santa Monica Blvd. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Laura Dickinson

CURRICULUM VITAE Laura Dickinson (202) 994-0376 (T) [email protected] EDUCATION Yale Law School, J.D., 1996 Journals: Co-Editor-in-Chief, Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities; Editor, Yale Law Journal Award: Khosla Memorial Fund for Human Dignity Prize for active engagement in advancing the values of human dignity in the international arena Activities: Teaching Assistant to Professor Harold Hongju Koh, Civil Procedure; Student Director, Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic Harvard College, A.B., Social Studies, 1992 Honors: Magna Cum Laude; Phi Beta Kappa Awards: Hoopes Prize for senior honors thesis; Harvard College Scholarship for academic achievement; Harvard National Scholar. Activities: Editorials Editor, Harvard Crimson; Chair, Phillips Brooks House Committee for Economic Change; Editor, Harvard Political Review ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2011 – present The George Washington University Law School Oswald Symister Colclough Research Professor of Law; Co‐Director, National Security Law Program 2008 – 2011 Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, Arizona State University Foundation Professor of Law; Director of the University’s Center for Law and Global Affairs 2001 – 2008 University of Connecticut School of Law Professor (2006-2008); Associate Professor (2001-2006) 2006 – 2007 Princeton University, Program in Law & Public Affairs Visiting Professor and Visiting Research Scholar JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS 1997 – 1998 United States Supreme Court, Washington, DC Law Clerk to Justice Harry A. Blackmun. Also performed full law clerk duties for Justice Stephen G. Breyer. 1996 – 1997 U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Pasadena, CA Law Clerk to Judge Dorothy W. Nelson OTHER WORK EXPERIENCE 2014 – present New America Foundation, Washington, DC Future of War Fellow Prepare reports, papers and presentations on legal issues arising from new techniques and methods of warfare. -

DA-05-2541A2.Pdf

LICENSEE ID # CALL SIGN LICENSEE NAME LICENSEE CITY STATE 5282 KIYU-AM Big River Broadcasting Corp Galena AK 43937 KKGO-AM Mt. Wilson FM Broadcasters Inc. Beverly Hills CA 35047 KLBM-AM Pacific Empire Radio Group La Grande OR 71211 KLIC-AM Media Ministries, Inc. Monroe LA 35107 KMA-AM KMA Broadcasting, LP Shenandoah IA 2910 KMYT-FM Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. Temecula CA 35289 KNBA-FM Koahnic Broadcast Corp. Anchorage AK 48974 KNIM-FM Nodaway Broadcasting Corp. Maryville MO 26892 KNTB-AM FTP Corporation Lakewood WA 37454 KNWI-FM Northwestern College Osceola IA 27077 KOHU-AM West-End Radio, LLC Hermiston OR 51128 KOLW-FM Capstar TX Limited Partnership Basin City WA 48674 KOPN-FM New Wave Corp. Columbia MO 34424 KOST-FM AM/FM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC Los Angeles CA 866 KOXR-AM Lazer Broadcasting Corporation Oxnard CA 22975 KPAY-AM Deer Creek Broadcasting, LLC Chico CA 51252 KPFK-FM Pacifica Foundation, Inc. Los Angeles CA 37153 KPOD-FM KPOD, LLC Crescent City CA 25515 KPRG-FM Guam Educational Radio Foundation Agana GU 60854 KPXP-FM Sorensen Pacific Broadcasting, Inc. Garapan/Saipan MP 19791 KQCS-FM Cumulus Licensing, LLC Bettendorf IA 90769 KQHR-FM KBPS Public Radio Foundation Hood River OR 5268 KQYX-AM Petracom of Joplin, LLC Joplin MO 29196 KRBT-AM Iron Range Broadcasting, Inc. Eveleth MN 30121 KRFO-AM Cumulus Licensing LLC Owatonna MN 72475 KSLM-AM Entercom Portland License, LLC Salem OR 5989 KSPT-AM Blue Sky Broadcasting Sandpoint ID 49016 KSYB-AM Amistad Communications, Inc. Shreveprot LA 73627 KTRF-AM Iowa City Broadcasting Co., Inc. -

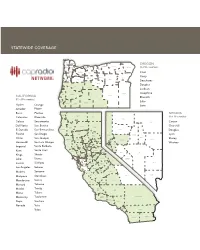

Statewide Coverage

STATEWIDE COVERAGE CLATSOP COLUMBIA OREGON MORROW UMATILLA TILLAMOOK HOOD WALLOWA WASHINGTON MULTNOMAH RIVER (9 of 36 counties) GILLIAM SHERMAN UNION YAMHILL CLACKAMAS WASCO Coos POLK MARION WHEELER Curry JEFFERSON BAKER LINCOLN LINN BENTON GRANT Deschutes CROOK Douglas LANE DESCHUTES Jackson MALHEUR Josephine COOS DOUGLAS HARNEY CALIFORNIA LAKE Klamath (51 of 58 counties) CURRY Lake KLAMATH JOSEPHINE JACKSON Alpine Orange Lane Amador Placer Butte Plumas NEVADA DEL NORTE SISKIYOU Calaveras Riverside MODOC (6 of 16 counties) HUMBOLDT Colusa Sacramento ELKO Carson Del Norte San Benito SHASTA LASSEN Churchill TRINITY El Dorado San Bernardino HUMBOLDT PERSHING Douglas TEHAMA Fresno San Diego WASHOE LANDER Lyon PLUMAS EUREKA Glenn San Joaquin MENDOCINO WHITE PINE Storey GLENN BUTTE SIERRA CHURCHILL STOREY Humboldt San Luis Obispo Washoe NEVADA ORMSBY LYON COLUSA SUTTER YUBA PLACER Imperial Santa Barbara LAKE DOUGLAS Santa Cruz YOLO EL DORADO Kern SONOMA NAPA ALPINE MINERAL NYE SACRAMENTO Kings Shasta AMADOR SOLANO CALAVERAS MARIN TUOLUMNE SAN ESMERALDA Lake Sierra CONTRA JOAQUIN COSTA MONO LINCOLN Lassen Siskiyou ALAMEDA STANISLAUS MARIPOSA SAN MATEO SANTA CLARA Los Angeles Solano MERCED SANTA CRUZ MADERA Madera Sonoma FRESNO SAN CLARK Mariposa Stanislaus BENITO INYO Mendocino Sutter TULARE MONTEREY KINGS Merced Tehama Trinity SAN Modoc LUIS KERN OBISPO Mono Tulare SANTA SAN BERNARDINO Monterey Tuolumne BARBARA VENTURA Napa Ventura LOS ANGELES Nevada Yolo ORANGE Yuba RIVERSIDE IMPERIAL SAN DIEGO CAPRADIO NETWORK: AFFILIATE STATIONS JEFFERSON PUBLIC STATION CITY FREQUENCY STATION CITY FREQUENCY FREQUENCY RADIO - TRANSLATORS KXJZ-FM Sacramento 90.9 KPBS-FM San Diego 89.5 Big Bend, CA 91.3 KXPR-FM Sacramento 88.9 KQVO Calexico 97.7 Brookings, OR 101.7 KXSR-FM Groveland 91.7 KPCC-FM Pasadena 89.3 Burney, CA 90.9 Stockton KUOP-FM 91.3 KUOR-FM Inland Empire 89.1 Callahan/Ft. -

2019 Public Participation Plan

metro.net/publicparticipationplan Public Participation Plan October 2019 Executive Summary The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) considers all who reside, work and travel within LA County to be stakeholders of the agency Residents, institutions, locally situated businesses, community- based organizations, religious leaders and the elected offi c ials who represent them are particularly important in relation to public participation planning and outreach Communications with the public is a continuum of involvement concerning service, fare changes, studies and initiatives, short- and long- range planning documents, environmental studies, project planning and construction, and transit safety education This Public Participation Plan (Plan) has been assembled to capture the methods, innovations and measurements of the agency’s commitment to meet and exceed the prescribed requirements of the U S Department of Transportation (USDOT), including Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Circulars C 4702 1B citing recipients’ responsibilities to Limited English Profic ient persons, FTA Circular C 4703 1, guiding recipients on integrating principles of Environmental Justice into the transportation decision-making process, and Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Title VI program The Plan is also consistent with Title VI, (non-discrimination regulations) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 162(a) of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973 and The Age Discrimination Act of 1975 Every three years, Metro updates the Public -

MO JAY RADIO . and Orchestra; Chausson, Curtain: Gounod, "Romeo

Slog In HI Ft: Liszt, "Les1 rang Interlude: "Aloha" Preludes"; Haydn, Syna-, with-the King Sisters. phony No. 102; Rodrigo, Concerto d'Ete for Violin10:00 p.m. ICBM. (105.1). Gold MO JAY RADIO . and Orchestra; Chausson, Curtain: Gounod, "Romeo . and Juliette" excerpts. MONDAY.A111LY27. 1977 7:00 a.m. IgtHtf (94.7), Paul4:00 p.m...KHCA_(10541,_MusIo Poeme for Violiipcj Or. 1100 p.m. KNOB (97.0). Act Portraits: Berlioz, "Sum---c-strar;-11e-ellicift-n-TQUAtc10:30-p.m.-KBIQ (1043), Exotic Lebec: Vocals a Audrey RUC KFI KHJ 920 ICPOL - 1540 Rhone: Music of Paul let No. 12. Sounds: "Exotic Dreams," Morris. Weston. nier Nights";DeJibes, Azama.-- KALI - 1430 KFOX - 1280KIEV. 870 KPOP 1020 "Sylvia.", 8:00 p.m. KCBH (98.7), Con- 11:30 p.m. KPFK , (00.7), Mod. KBIG-740 11:00 p.m. KPFK (90.7). Mod. KFWB 980KLAC 570 ° 7:00 a.m. KNOB (97.9). Java5:90.p.m. ERH111 (94.7), Strict- certo: Handel, Organ Con. ern Jazz Scene: With Philp %MA 1490; Ktrizw.,.1130 With Jazz: "Swingin' Lov- em Jazz: Gerry Mulligan ip Elwood in weekly so gpAy .1580 . KGER, 1390KI6PC ly Dixie: Artistry of Bob certo No. 14;Paganini, 710 .KINIZ .1400 ers," Frank Sinatra. ViolinConcerto No.4: Quartette. ries. 1190KGFJ - 1230 KNX 1070 MOW - 1600 Scobey and the Dukes of Chausson, Symphony In KEZY'KFAC1/-'1330 KGIL 1260, MAC 1560 KXLA 1110 8:00 a.m. KCBH (98.7), Inter- lude: Offenbach, "Grand Dixieland. B Fla t:Rachmaninoff, 5:00 p.m. KPFK (90.7); Pro. -

Pedone, Ronald J. Status,Report on Public Broadcasting, 1973. Advanc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 365 95 /R 001 757 AUTHOR Lee, S. Young; Pedone, Ronald J. TITLE Status,Report on Public Broadcasting, 1973. Advance Edition. Educational Technology Series. INSTITUTION Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C.; Nationil Cener for Education Statistics (DREW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Dec 74 NOTE 128p. EDRS PRICE MF-S0.76HC-66.97 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Annual Reports; Audiences; *Broadcast Industry; *Educational Radio; Educational Television; Employment Statistics; Financial Support; Media Research; Minority Groups; Programing (Broadcast); *Public Television; Statistical Studies; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Corporation for Public Broadcasting; CPB; PBS; Public Broadcasting Service ABSTRACT I statistical report on public broadcasting describes the status of the industry for 1973. Six major subject areas are covered: development of public broadcasting, finance, employment, broadcast and production, national interconnection services, and audiences of public broadcasting. Appendixes include supplementary tables showing facilities, income by source and state, percent distribution of broadcait hours, in-school broadcast hodrs, and listings of public radio and public television stations on the air as of June 30, 1973. There are 14 figures and 25 summary tables. (SK) A EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY k STATUS REPORT ON I :I . PUBLIC BROADCASTING 1973 US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION &WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO OUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM 14E PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN -

Agenda Metro Sustainability Council

Friday, December 14, 2018 @ 9:00 –11:00 am Agenda Metro Sustainability Council LA Metro HQ William Mulholland 15th Floor One Gateway Plaza Los Angeles, CA Agenda a. Welcome/Introductions: Chair (5 min) Meetings ARC Update Vacant Seat Nominations Update b. Approval of Minutes: Chair (5 min) c. CAAP Workshop Introduction: Evan Rosenberg (10 min) d. CAAP Breakout Sessions (55 min) e. Breakout Sessions Recap (15 min) f. DRAFT EV Implementation Strategy: Andrew Quinn (10 min) g. Action Items Log: Aaron (2 min) Sustainab ilityCouncil FY19 DRAFTM e e tingsArc AsofDe ce m b e r5,2018 M e e ting Ag e nd a Topics Outcom e s Se ptem b e r21,2018 *Ne w M e troRole *Bylawsa m e nd e d toreflectnew M e trorole *M otion57Progress *Allparticipantslea ve m e e ting witha Upd a te b a sic und e rstand ing ofMe tro’s currentprogressrelated toM otion57 Octob e r12,2018 *Introd uce Clima te Action *Allparticipantslea ve m e e ting witha Plan(CAAP) Upd a te topic b a sic und e rstand ing ofMe tro’s currentpractice srelated toCAAP,as we lla sb e stpractice sinthisfield (related totransportationprojects), a nd cha llenge srelated tothistopic. *Directionprovide d from the Council toM e trostaffond e veloping initial recomm e nd a tionsonCAAP upd a te; a d d itionalinforma tionnee d s ide ntified *OralUpd a te onLRTP *Allparticipantslea ve m e e ting witha Outrea ch a nd Activities b a sic und e rstand ing ofthe LRTP d e velopm e ntprogressa nd provide fee d b a ck a spartofthe outrea ch e ffort. -

Festival Handbook

This booklet was inspired by and written for participants in the Festival Encouragement Project (FEP), a program co-created in 2003 by the Center for Cultural Innovation and supported by a grant from the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs (LADCA). The goal of 2 the FEP is to build the strength and capacity of selected outdoor cultural celebrations produced in L.A. that serve residents and tourists. Book Photography: Aaron Paley Book Design: Peter Walberg Published by the Center for Cultural Innovation TABLE OF CONTENTS Artists shown on the following pages: INTRODUCTION Judith Luther Wilder Cover Dragonfly by Lili Noden’s Dragon Knights ONE Festivals: Their Meaning and Impact in the City of Angels Page 2 Titus Levi, PhD. Jason Samuels Smith, Anybody Can Get It TWO Page 4 A Brief Historical Overview of Selected Festivals in Los Angeles- 1890-2005 Nathan Stein Aaron Paley Page 6 THREE Tracy Lee Stum Madonnara, Street painter Why? An Introduction to Producing a Festival Hope Tschopik Schneider Page 7 Saaris African Foods FOUR Santa Monica Festival 2002 Choosing Place: What Makes a Good Festival Site? Page 9 Maya Gingery Procession, streamers by Celebration Arts Holiday Stroll in Palisades Park, FIVE Santa Monica Timelines & Workplans Page 11 Aaron Paley Body Tjak, created by I Wayan Dibia and Keith Terry SIX Santa Monica Festival 2002 The Business Side of Festivals Sumi Sevilla Haru Page 12 Ricardo Lemvo and Makina Loca on stage at POW WOW SEVEN Grand Avenue Party 2004 Public Relations Advice for Festival Producers