The Second Shamnad Basheer Essay Competition on Intellectual Property Law (2021)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Pranab Mukherjee Praises Narendra Modi Govt for 1 July Rollout

7/5/2017 GST: President Pranab Mukherjee praises Narendra Modi govt for 1 July rollout Wednesday, July 05, 2017 Switch(/) to हद (http://hindi.firstpost.com/) GST: President Pranab Mukherjee praises Narendra Modi govt for 1 July rollout Kolkata: Praising the central government's move to roll out the Goods and Services Tax (GST) from 1 July, President Pranab Mukherjee on Thursday said it will put an end to the burden of multiplicity of taxes that the citizens had to pay so far. Thanking Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley for pushing through a single tax system for the country's 130 crore people, Mukherjee said so long consumers had to shell out 30 to 40 percent more on the cost of production of goods and services. File image of Pranab Mukhjerjee. PTI Mukherjee, who was addressing a Global Summit organised by The Institute of Cost Accountants of India here, recalled how he and other nance ministers in the past had made futile attempts to introduce the GST. "From the days of Yashwant Sinha, who was nance minister in Vajpayee government, to my days in nance ministry before I assumed the ofce of president, we tried to have the GST. I introduced in 2011 a Constitutional Amendment Bill to facilitate the GST. But it could not go through," he said. The president said he at times wondered why the process of change was slow, but then remembered that the ethos of India lay in its philosophy of unity in diversity. The country has wide-ranging diversity, with a population of 1.3 billion, and people speaking around 200 languages, 1,800 dialects, practising seven major religions and belonging to three major ethnic groups. -

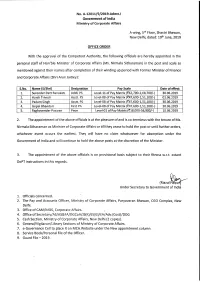

Office Order Dated 20 June 2019

--------~--.------ No. A-12011/9/2019-Admn.1 Governmentof India Ministry of Corporate Affairs A-wing, 5th Floor, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi, dated: 19th June, 2019 OFFICE ORDER With the approval of the Competent Authority, the following officials are hereby appointed in the personal staff of Hon'ble Minister of Corporate Affairs (Ms. Nirmala Sitharaman) in the post and scale as mentioned against their names after completion of their winding up period with Former Minister of Finance and Corporate Affairs (Shri Arun Jaitley): S.No. Name (S/Shri) Designation Pay Scale Date of effect 1. Surender Datt Ranakoti Add!. PS Level-ll of Pay Matrix (~67,700-2,08,700/-) 30.06.2019 2. Harsh Trivedi Asstt. PS Level-08 of Pay Matrix (~47,600-1,51,100/-) 01.06.2019 3. Padam Singh Asstt. PS Level-08 of Pay Matrix (~47,600-1,51,100/-) 30.06.2019 4. Gopal Bhandari First PA Level-08 of Pay Matrix (~47,600-1,51,100/-) 30.06.2019 I 5. Raghavender Paswan Peon Level-Olaf Pay Matrix (~18,000-56,900/-) 15.06.2019 2. The appointment of the above officials is at the pleasure of and is co-terminus with the tenure of Ms. Nirmala Sitharaman as Minister of Corporate Affairs or till they cease to hold the post or until further orders, whichever event occurs the earliest. They will have no claim whatsoever for absorption under the Government of India and will continue to hold the above posts at the discretion of the Minister. 3. The appointment of the above officials is on provisional basis subject to their fitness w.r.t. -

Banalities Turned Viral: Narendra Modi and the Political Tweet

TVNXXX10.1177/1527476415573956Television & New MediaPal 573956research-article2015 Article Television & New Media 1 –10 Banalities Turned Viral: © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Narendra Modi and the sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1527476415573956 Political Tweet tvn.sagepub.com Joyojeet Pal1 Abstract Narendra Modi’s social media presence is among the most extensive for any politician in the world, including on Twitter where he currently stands second in following only to Barack Obama. With a mix of “feel good” messages, shout-outs to other celebrities, and well-timed ritualized responses, as well as a careful strategy of “followbacks” for a small selection of his most active followers, Modi has been able to grow his following dramatically especially since 2013. Twitter helps Modi directly reach a significant constituency of listeners, and use it as a channel to talk to the main stream media. In addition, the very appearance of his using social media effectively is in itself valuable in reshaping his public image as a technology-savvy leader, aligned with the aspirations of a new Indian modernity. Keywords Narendra Modi, Twitter, social media, politics, India, BJP, campaign, followback, new media, Facebook, NaMo, RSS The most “retweeted” and “favorited” message in India’s social media history came on May 15, 2014, when the handle @narendramodi tweeted “India has Won.” The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had come to power in elections with the biggest mandate in three decades, and Narendra Modi would be the next prime minister. The carefully phrased victory tweet congratulated the social media supporters who had for months been his online foot soldiers. -

Notification

(TO BE PUBLISHED IN GAZETTE EXTRA ORDINARY, PART 1 – SEC.1) Government of India Ministry of Culture (Special Cell) Notification New Delhi, the 24th September, 2016 F.No. 19-1/2015- Special Cell – To commemorate the Birth Centenary of Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya in a befitting manner, the Competent Authority has approved the constitution of a National Committee. The composition of the National Committee is as under:- NATIONAL COMMITTEE Chairman 1. Shri Narendra Modi, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India Members 2. Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Fr PM, Bharat Ratna 3. Shri H D Deve Gowda, Fr PM of India 4. Smt. Sumitra Mahajan, Speaker of Lok Sabha 5. Shri Rajnath Singh, Home Minister 6. Smt. Sushma Swaraj, External Affairs Minister 7. Shri Arun Jaitley, Finance Minister 8. Shri Manohar Parikkar, Defence Minister 9. Shri Venkaiah Naidu, Urban Development Minister 10. Shri Nitin Gadkari, Minister of Road Transport & Highways & Shipping 11. Shri Suresh Prabhu, Minister of Railways 12. Shri Ram Vilas Paswan, Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution 13. Shri Kalraj Mishra, Minister of MSME 14. Shri Jual Oram, Minister of Tribal Affairs 15. Shri Thaawar Chand Gehlot, Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment 16. Shri Prakash Javadekar, Minister of Human Resource Development 17. Ms Lata Mangeshkar, Bharat Ratna 18. Shri Mahesh Sharma, MoS (IC), Culture 19. Shri Anil Madhav Dave, Environment Minister - MoS (IC) 20. Shri L K Advani, Fr Dy. PM 21. Smt. Mridula Sinha, Governor of Goa 22. Prof. O P Kohli, Governor of Gujarat 23. Prof. Kaptan Singh Solanki, Governor of Haryana 24. Shri Acharya Devvrat, Governor of Himachal Pradesh 25. -

Batch Wise List, Please See Below

DELHI & DISTRICT CRICKET ASSOCIATION (AFFILIATED TO THE BOARD OF CONTROL FOR CRICKET IN INDIA) ARUN JAITLEY STADIUM FEROZSHAH KOTLA GROUND, NEW DELHI-110002 Date: 25/08/2021 DDCA is conducting Men's Under-19 Preliminary Trials from 26-08-2021 at Palam Airforce Cricket Ground. The schedule of trials is as under:- S.No Date Batch Time Reporting Time 1. 26-08-2021 Batch-1 09:00 AM to 12:00 NOON 08:30 AM 2. 26-08-2021 Batch-2 01:00 PM to 04:00 PM 12:30 PM 3. 27-08-2021 Batch-3 09:00 AM to 12:00 NOON 08:30 AM 4. 27-08-2021 Batch-4 01:00 PM to 04:00 PM 12:30 PM 5. 28-08-2021 Batch-5 09:00 AM to 12:00 NOON 08:30 AM 6. 28-08-2021 Batch-6 01:00 PM to 04:00 PM 12:30 PM INSTRUCTIONS FOR PLAYERS 1. Parking is not allowed at the venue. 2. Parents are not allowed inside the ground premises. 3. All the players are advised to wear Proper White Sports Dress. 4. Venue : Palam Air force Ground , New Delhi 5. Enclosed: Batch wise list, Please See Below. “This is an electronically generated note, hence does not require a signature” FOR & on behalf of DELHI & DISTRICT CRICKET ASSOCIATION BATCH-1 S.no NAME OF THE PLAYER Proficiency Specialization Date of Birth Father Name / Mother Name 1 Nitesh kumar sharma All Rounder Opening Batsmen, Right Arm Fast Bowler 06-07-2005 Sh. Joginder kumar Sharma 2 Dev Lakra All Rounder Opening Batsmen, Middle Order Batsmen 27-01-2003 Dharmender 3 piyush mathur All Rounder Middle Order Batsmen 25-12-2003 Vijay Mathur 4 Piyush All Rounder Opening Batsmen, Off Spinner (RAOS) 03-07-2003 Sundar singh 5 AYUSH SAINI All Rounder Right -

Jaitley, Chidambaram Share Stage to Agree, Disagree

Jaitley, Chidambaram share stage to agree, disagree Both find common ground on insurance FDI; while Jaitley rapped UPA for derailing the economy, Chidambaram took on NDA govt for not repealing retro tax amendment It was a clash of ideas between Finance Minister Arun Jaitley and his predecessor P Chidambaram but a debate between the two also saw them agree broadly on raising the cap on foreign investment in insurance companies. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Jaitley had spoken about tough decisions but Chidambaram took on the National Democratic Alliance government for not taking these very measures, including repealing of the retrospective amendments to the Income Tax Act. Jaitley's predecessor conceded the mistakes made by the Manmohan Singh government, saying it should have cancelled 2G telecom licences when the scam surfaced, without waiting for court judgment. Jaitley accused the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government of continuing with the practice of discretionary allocation in coal, even after the report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG). He charged the UPA regime with derailing the economy that yielded under five per cent growth for consecutive years. "You have the biggest majority in 30 years. In my 12 years as finance minister, had I had that kind of majority, I would have taken tougher decisions. I would have repealed the retrospective tax laws, for instance. It just takes a few amendments in the Income Tax Act. I was hoping you would do that and I am still hoping that you do," said Chidambaram in the debate with Jaitley during the launch of television journalist Rajdeep Sardesai's book 2014: The Elections That Changed India. -

1. the Indian Railways Are Constructing the World's

DAILY CURRENT AFFAIR QUIZ DAILY CURRENT AFFAIR QUIZ : (17 AUG TO 19 AUG 2020) No. of Questions: 20 Correct: Full Mark: 20 Wrong: Time: 15 min Mark Secured: 1. The Indian Railways entity? are constructing the A) Rs 500 crore world’s tallest pier B) Rs 200 crore bridge in which state C) Rs 300 crore of India? D) Rs 400 crore A) Tripura 5. Satya Pal Malik has B) Jammu & Kashmir recently been C) Odisha appointed as the D) Manipur Governor of which 2. Which institute has state? topped the ‘Atal A) Nagaland Ranking of Institutions B) Madhya Pradesh on Innovation C) Goa Achievements,’ D) Meghalaya (ARIIA) 2020? 6. Who was the A) IIT Delhi representative from B) IIT Madras India side in the 13th C) IIT Bombay Session of the India- D) IISc Bengaluru UAE Joint Commission 3. Government has Meeting (JCM) on decided to name the Trade, Economic and Gwalior-Chambal Technical Expressway after Cooperation? which Indian political A) Piyush Goyal leader? B) Nirmala Sitharaman A) A. P. J. Abdul C) Subrahmanyam Kalam Jaishankar B) Arun Jaitley D) Rajnath Singh C) Atal Bihari 7. In the modified Partial Vajpayee Credit Guarantee D) Sushma Swaraj Scheme (PCGS) 2.0, 4. RBI has released the what is the limit set for ‘framework for the AA and AA- authorization of pan- investment sub- India Umbrella Entity portfolio at portfolio for Retail Payments’ in level, of the total India. What shall be portfolio of Bonds/ the minimum paid-up CPs? 1 capital of the umbrella A) 35% 1441, Opp. IOCL Petrol Pump, CRPF Square, Bhubaneswar-750015 Ph. -

70 POLICIES THAT SHAPED INDIA 1947 to 2017, Independence to $2.5 Trillion

Gautam Chikermane POLICIES THAT SHAPED INDIA 70 POLICIES THAT SHAPED INDIA 1947 to 2017, Independence to $2.5 Trillion Gautam Chikermane Foreword by Rakesh Mohan © 2018 by Observer Research Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from ORF. ISBN: 978-81-937564-8-5 Printed by: Mohit Enterprises CONTENTS Foreword by Rakesh Mohan vii Introduction x The First Decade Chapter 1: Controller of Capital Issues, 1947 1 Chapter 2: Minimum Wages Act, 1948 3 Chapter 3: Factories Act, 1948 5 Chapter 4: Development Finance Institutions, 1948 7 Chapter 5: Banking Regulation Act, 1949 9 Chapter 6: Planning Commission, 1950 11 Chapter 7: Finance Commissions, 1951 13 Chapter 8: Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951 15 Chapter 9: Indian Standards Institution (Certification Marks) Act, 1952 17 Chapter 10: Nationalisation of Air India, 1953 19 Chapter 11: State Bank of India Act, 1955 21 Chapter 12: Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, 1955 23 Chapter 13: Essential Commodities Act, 1955 25 Chapter 14: Industrial Policy Resolution, 1956 27 Chapter 15: Nationalisation of Life Insurance, 1956 29 The Second Decade Chapter 16: Institutes of Technology Act, 1961 33 Chapter 17: Food Corporation of India, 1965 35 Chapter 18: Agricultural Prices Commission, 1965 37 Chapter 19: Special Economic Zones, 1965 39 iv | 70 Policies that Shaped India The Third Decade Chapter 20: Public Provident Fund, 1968 43 Chapter 21: Nationalisation of Banks, 1969 45 Chapter -

India's Domestic Political Setting

July 9, 2014 India’s Domestic Political Setting Overview India, the world’s most populous democracy, is, according BJP’s outright majority victory—remains an important to its Constitution, a “sovereign, socialist, secular, variable in Indian politics. Such parties now hold more than democratic republic” where the bulk of executive power 200 seats in parliament. Some 464 parties participated in rests with the prime minister and his Council of Ministers the 2014 national election and 35 of those won (the Indian president is a ceremonial chief of state with representation. The 8 parties listed below account for 67% limited executive powers). Since its 1947 independence, of the total vote and 85% of Lok Sabha seats (see Figure 1). most of India’s 14 prime ministers have come from the country’s Hindi-speaking northern regions and all but three Figure 1. Major Party Representation in the Lok Sabha have been upper-caste Hindus. The 543-seat, Lok Sabha (543 Total Seats + 2 Appointed) (House of the People) is the locus of national power, with directly elected representatives from each of the country’s 29 states and 7 union territories. The president has the power to dissolve this body. A smaller upper house of a maximum 250 seats, the Rajya Sabha (Council of States), may review, but not veto, revenue legislation, and has no power over the prime minister or his/her cabinet. Lok Sabha and state legislators are elected to five-year terms. Rajya Sabha legislators are elected by state legislatures to six-year terms; 12 are appointed by the president. -

List of Finance Minister of India – PDF Download

List of Finance Minister of India – PDF Download Dear Friends, Hereby we have provided List of Finance Minister of India from 1947 to till date. The name of all previous Finance Ministers and their tenure has been provided in the PDF format. R.K. Shanmukham Chetty was the first Finance Minister of Independent India. Name Political Party & Alliance Tenure R. K. Shanmukham Indian National Congress 15th August 1947 – 1949 Chetty John Mathai Indian National Congress 1949 - 1950 C. D. Deshmukh Indian National Congress 29th May 1950 - 1957 T. T. Krishnamachari Indian National Congress 1957 – 13th February 1958 Jawaharlal Nehru Indian National Congress 13th February 1958 - 13th March 1958 Morarji Desai Indian National Congress 13th March 1958 - 29th August 1963 T. T. Krishnamachari Indian National Congress 29th August 1963 - 1965 Sachindra Chaudhuri Indian National Congress 1965 - 13th March 1967 Morarji Desai Indian National Congress 13th March 1967 - 16th July 1969 Indira Gandhi Indian National Congress 1970 -1971 Yashwantrao Chavan Indian National Congress 1971 – 1975 Chidambaram Indian National Congress Subramaniam 1975 – 1977 Janata Party 24th March 1977 - 24th January Hirubhai M. Patel 1979 Janata Party 24th January 1979 - 28th July Charan Singh 1979 Hemvati Nandan 28th July 1979 - 14th January Bahuguna Janata Party (Secular) 1980 14th January 1980 - 15th R. Venkataraman Indian National Congress January 1982 15th January 1982 - 31st Pranab Mukherjee Indian National Congress December 1984 31st December 1984 - 24th V. P. Singh Indian National -

Declaration of Assets and Liabilities by Shri Arun

DECLARATION OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES BY SHRI ARUN JAITLEY MEMBERS OF RAJYA SABHA [UNION MINISTER OF FINANCE AND CORPORATE AFFAIRS] FORM 1 (See Rule 3) A. Information Of Assets & Liabilities As On 31.03.2018 of SHRI ARUN JAITLEY 1. Name of the Member SH. ARUN JAITLEY 2. Father's Name LATE SHRI MAHARAJ KRISHAN 3. Permanent Address 6, Tapas Bunglows, Nr. Auda Garden Prahlad Nagar, Sector-2, Vejalpur, Ahmedabad — 380051 4. Delhi Address A-44, Kailash Colony, New Delhi — 110048 5. Party Affiliation Bharatiya Janata Party 6. Date of Election 23rd MARCH 2018 7. Date Of Taking Oath/ 15th APRIL 2018 Making Affirmation (I) Details of immovable property Annexure A Lands! Sites Annexure B Commercial Properties Annexure C Residential Properties (ii) Details of movable property Annexure D Details of Vehicles owned Annexure E Details of Gold, Silver and Diamonds Annexure F Bank Balance Annexure G Other Movable Assets (iii) Details of liabilities to public Financial institutions/Central Government/State Governments & others (a) Public Financial Institutions NIL (b) Central Government NIL (c) State Government NIL (d) Others NIL B. Information Of Assets & Liabilities As On 31.03.2018 of Smt. SANGEETA JAITLEY w/o SHRI ARUN JAITLEY 1. Name SMT. SANGEETA JAITLEY 2. Father's Name LATE SH. GIRDHARI LAL DOGRA 3. Permanent Address 6, Tapas Bunglows, Nr. Auda Garden Prahlad Nagar, Sector-2, Vejalpur, Ahmedabad — 380051 4. Delhi Address A-44, Kailash Colony, New Delhi — 110048 (I) Details of immovable property Annexure H Commercial Properties Annexure I Residential Properties (ii) Details of movable property Annexure J Details of Gold, Silver nd Diamonds Annexure K Bank Balance Annexure L Other Movable Assets (iii) Details of liabilities topublic Financial institutions/Central Government/State Governments & others : (a) Public Financial Institutions NIL (b) Central Government NIL (c) State Government NIL (d) Others Annexure M C. -

PUBLIC AI Index: ASA 20/35/00 25 July 2000

PUBLIC AI Index: ASA 20/35/00 25 July 2000 Further information on EXTRA 154/99 (ASA 20/38/99, 4 November 1999) and follow-ups (ASA 20/39/99, 5 November 1999, ASA 20/06/00, 15 March 2000, ASA 20/29/00, 10 July 2000 and ASA 20/30/00, 13 July 2000) - Death Penalty / Fear of Imminent Execution INDIAGovindaswamy Govindaswamy’s execution has been stayed until 7 August. The Ministry of Home Affairs in New Delhi ordered the 14-day stay on 21 July, two days before he was scheduled to be hanged. No reason has been given for the stay of execution. FURTHER RECOMMENDED ACTION: Please send telegrams/faxes/express/airmail letters in English or your own language: - welcoming the temporary stay of execution but expressing concern that a further date has been set; - expressing grave concern that the President of India has rejected Govindaswamy’s clemency petition; - urging the authorities to use the 14-day stay to carefully consider the setback to human rights in India that this execution would signal; - calling for Govindaswamy’s death sentence to be commuted to a term of imprisonment; - expressing unconditional opposition to the death penalty as a violation of the right to life and the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and emphasising that the death penalty has never been shown to have a special deterrent effect. APPEALS TO: Mr K.R. Narayanan President of India Office of the President Rashtrapati Bhavan New Delhi 110 004, India Telegrams: President, New Delhi, India Faxes: + 91 11 301 7290 / 7824 / 7077 Salutation: Dear President Narayanan Mr L.K.