Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color | National Gallery of Canada 2017-10-18, 7�42 AM

Donʼt Take My Kodachrome Away — A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color | National Gallery of Canada 2017-10-18, 742 AM Don’t Take My Kodachrome Away — A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color Sheila Singhal October 17, 2017 One of the things that strikes a viewer almost immediately when presented with an array of Fred Herzog’s photographs is the pop of “Kodachrome red” that appears in almost every image. Whether in the tights of a young girl and the nearby skirt of an older woman in Red Stockings (1961), or in the signage of Empty Barber Shop (1966), or in a painted billboard for Buckingham cigarettes in Elysium Cleaners (1958), Herzog includes the hue in the large majority of his photographs. “Kodachrome red, available only in slides, was his muse,” writer and critic Sarah Milroy has said, “and many of his best works are anchored in this primary hue.” Fred Herzog, Red Stockings, 1961. © Fred Herzog, Courtesy Equinox Gallery https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/books/dont-take-my-kodachrome-away-a-review-of-fred-herzog-modern-color Page 1 of 9 Donʼt Take My Kodachrome Away — A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color | National Gallery of Canada 2017-10-18, 742 AM In the new book, Fred Herzog: Modern Color, the photographer’s masterful use of colour is on full display. A quintessential mid-20th-century street photographer, Herzog captures daylit streets crammed with shop signs and people. At night, the neon lights of a gloriously gaudy Vancouver float in the darkness like fireflies in pitch. Open lots with wrecked and decaying automobiles sit cheek by jowl with down-at-heel businesses on forgotten street corners. -

Ingram 2010 Squatting in 'Vancouverism'

designs for The Terminal City www.gordonbrentingram.ca/theterminalcity 21 March, 2010 Gordon Brent Ingram Re-casting The Terminal City [part 3] Squatting in 'Vancouverism': Public art & architecture after the Winter Olympics Public art was part of the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver; there was some funding, some media coverage, and a few sites were transformed. What were the new spaces created and modes of cultural production, in deed the use of 21 March, 2010 | Gordon Brent Ingram Squatting in 'Vancouverism': Public art & architecture after the Winter Olympics designs for The Terminal City www.gordonbrentingram.ca/theterminalcity page 2 culture in Vancouver, that have emerged in this winter of the Olympics? What lessons can be offered, if any, to other contemporary arts and design communities in Canada and elsewhere? And there was such celebration of Vancouver, that a fuzzy construct was articulated for 'Vancouverism' that today has an unresolved and sometimes pernicious relationship between cultural production and the dynamics between public and privatizing art. In this essay, I explore when, so far, 'Vancouverism'1 has become a cultural, design, 'planning', or ideological movement and when the term has been more of a foil for marketing over‐priced real estate.2 In particular, I am wondering what, in these supposedly new kinds of Vancouveristic urban designs, are the roles, 'the place' of public and other kinds of site‐based art. The new Woodward's towers and the restored Woodward's W sign from the historic centre of 19th Century Vancouver at Carrall and Water Street, January 2010, photograph by Gordon Brent Ingram 21 March, 2010 | Gordon Brent Ingram Squatting in 'Vancouverism': Public art & architecture after the Winter Olympics designs for The Terminal City www.gordonbrentingram.ca/theterminalcity page 3 January and February 2010 were the months to separate fact from fiction and ideas from hyperbole. -

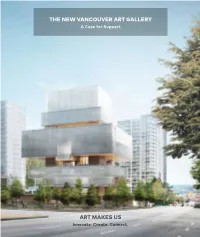

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY a Case for Support

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY A Case for Support A GATHERING PLACE for Transformative Experiences with Art Art is one of the most meaningful ways in which a community expresses itself to the world. Now in its ninth decade as a significant contributor The Gallery’s art presentations, multifaceted public to the vibrant creative life of British Columbia and programs and publication projects will reflect the Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has embarked on diversity and vitality of our community, connecting local a transformative campaign to build an innovative and ideas and stories within the global realm and fostering inspiring new art museum that will greatly enhance the exchanges between cultures. many ways in which citizens and visitors to the city can experience the amazing power of art. Its programs will touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, through remarkable, The new building will be a creative and cultural mind-opening experiences with art, and play a gathering place in the heart of Vancouver, unifying substantial role in heightening Vancouver’s reputation the crossroads of many different neighbourhoods— as a vibrant place in which to live, work and visit. Downtown, Yaletown, Gastown, Chinatown, East Vancouver—and fuelling a lively hub of activity. For many British Columbians, this will be the most important project of their Open to everyone, this will be an urban space where museum-goers and others will crisscross and encounter generation—a model of civic leadership each other daily, and stop to take pleasure in its many when individuals come together to build offerings, including exhibitions celebrating compelling a major new cultural facility for its people art from the past through to artists working today— and for generations of children to come. -

Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’S 2016 Media Kit

Assignment: Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’s 2016 Media Kit TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 4 WHERE IN THE WORLD IS VANCOUVER? ........................................................ 4 VANCOUVER’S TIMELINE.................................................................................... 4 POLITICALLY SPEAKING .................................................................................... 8 GREEN VANCOUVER ........................................................................................... 9 HONOURING VANCOUVER ............................................................................... 11 VANCOUVER: WHO’S COMING? ...................................................................... 12 GETTING HERE ................................................................................................... 13 GETTING AROUND ............................................................................................. 16 STAY VANCOUVER ............................................................................................ 21 ACCESSIBLE VANCOUVER .............................................................................. 21 DIVERSE VANCOUVER ...................................................................................... 22 WHERE TO GO ............................................................................................................... 28 VANCOUVER NEIGHBOURHOOD STORIES ................................................... -

Reimagining Vancouver's Skid Road Through the Photography Of

“Addicts, Crooks, and Drunks”: Reimagining Vancouver’s Skid Road through the Photography of Fred Herzog, 1957–70 Tara Ng A Thesis in The Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Art History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2016 © Tara Ng, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Tara Ng Entitled: “Addicts, Crooks, and Drunks”: Reimagining Vancouver’s Skid Road through the Photography of Fred Herzog, 1957–70 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Art History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _____________________________________ Chair _____________________________________Examiner Dr. Catherine MacKenzie _____________________________________Examiner Dr. Cynthia Hammond _____________________________________Supervisor Dr. Martha Langford Approved By ______________________________ Dr. Alice Ming Wai Jim Graduate Program Director ________________2016 ______________________________ Rebecca Taylor Duclos Dean of Faculty of Fine Arts iii Abstract “Addicts, Crooks, and Drunks”: Reimagining Vancouver’s Skid Road through the Photography of Fred Herzog, 1957–70 Tara Ng This thesis explores how Canadian artist Fred Herzog’s (b. 1930) empathetic photographs of unattached, white, working-class men living on Vancouver’s Skid Road in the 1950s and 1960s contest dominant newspaper representations. Herzog’s art practice is framed as a sociologically- oriented form of flânerie yielding original, nuanced, and critical images that transcend the stereotypes of the drunk, the criminal, the old-age pensioner, and the sexual deviant on Skid Road. -

Toronto's Vancouverism: Developer Adaptation, Planning Responses, and the Challenge of Design Quality

White, J. T., and Punter, J. (2017) Toronto's Vancouverism: developer adaptation, planning responses, and the challenge of design quality. Town Planning Review, 88(2), pp. 173-200. (doi:10.3828/tpr.2016.45) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/114514/ Deposited on: 20 January 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk33640 Toronto’s ‘Vancouverism’: Developer adaptation, planning responses, and the challenge of design quality JAMES T. WHITE AND JOHN PUNTER Abstract This paper examines ‘Vancouverism’ and its recent reproduction at CityPlace on Toronto’s Railway Lands. The developers, Concord Pacific, were centrally involved in producing ‘Vancouverism’ in the 1990s and 2000s. This study examines the design quality of CityPlace and explores the differences between the planning cultures in Vancouver and Toronto. In evaluating the design outcomes it highlights a mismatch between the public sector’s expectations, the developer’s ambitions and the initial design quality. The paper demonstrates that, despite an increasingly sophisticated system of control, the City of Toronto’s ability to shape outcomes remains limited and, overall, the quality of development falls short of that achieved in Vancouver. Key Words Urban Design; Design control; Toronto; Vancouver Words: 8,797 (excl. abstract and key words) 1 Introduction Vancouver, on Canada’s West Coast, is widely recognised for its design-sensitive approach to city planning and development management (Punter, 2003). -

Fred Herzog: Vancouver

Fred Herzog: Vancouver June 26th to September 12th, 2008 at the Canadian Cultural Centre th Opening: June 25 at 6PM with Fred Herzog Media Contact: The Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris, in collaboration T. (+33) 1 44 43 21 49 / (+33) 1 44 43 21 55 with Equinox Gallery (Vancouver, Canada), presents the [email protected] first solo exhibition in Europe by German-born photog- rapher Fred Herzog who immigrated to Canada in 1953. This European premiere follows the showing of Van- couver Photographs, the successful retrospective exhib- ition of the artist’s work presented at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2007. The photographs of Fred Herzog were shown at ARCO this year by Trepanier Baer Gallery (Cal- gary) and were presented at two major exhibitions this past spring, at the Equinox Gallery and at the Laurence Miller Gallery in New York. Vancouver brings together a selection of prints from the large photographic body of work that Herzog dedicated to Canada’s West Coast capital, his adoptive city. In them, we see develop- ment, expansion, projects, people, extraordinary lights but also the darker side of a city that saw an uncommonly rapid expansion in the span of only a few decades, mainly due to immigration, most notably that of Asian newcomers. Herzog spent more than half a century wandering through the streets of Vancouver with his camera. His lens focussed particularly on marginal areas, peripheral to the splendours of the bud- ding city: second-hand shops, abandoned lots, barber shops, greasy spoon diners, crowded areas full of dreams, but also of disillusion. -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Vancouver Art Gallery Presents BC's Premier Visual Arts Prizes on April 15: Audain Prize, VIVA Awards April 11, 2014, Vancouver, B.C. – The visual arts in British Columbia will be celebrated as three distinguished artists receive the most prestigious awards in this province: the Audain Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts and the VIVA Awards. This year, Fred Herzog is awarded the 12th Audain Prize, funded by the Audain Foundation for the Visual Arts, and Skeena Reece and Mina Totino are each the recipient of the VIVA Award granted annually by the Jack and Doris Shadbolt Foundation. To mark this annual celebration with the visual arts community, a ceremony honouring the artists will be held at 7:00 pm on Tuesday, April 15 in The Great Hall of the BC Law Courts building in downtown Vancouver. “We are extremely honoured to present this year’s Audain Prize and VIVA Awards. These awards exemplify the high standards set by artists of our region,” said the Vancouver Art Gallery’s Director Kathleen S. Bartels. “All three artists have shown at the Vancouver Art Gallery – Fred Herzog’s first major exhibition was organized by the Gallery in 2007, Skeena Reece was an integral part of the Beat Nation exhibition in 2012, and Mina Totino has been included in many exhibitions at the Gallery since 1985. We congratulate all of them and celebrate the career achievements of these outstanding British Columbia artists.” Established in 2004, the Audain Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts has become one of Canada’s most esteemed honours. -

At the Gallery Save the Date

Chris Millar, Gutterballs - Back Cover, 2011, Acrylic on wood panel, 8.5” x 8.5” at the gallery save the date Chris Millar – september 8th through to October 8th, 2011 TrépanierBaer is pleased to present an exhibition of new works by Chris Millar, opening on Thursday, September 8th. Millar has been labouring fastidiously in his studio while attending various musical venues throughout the city of Calgary (he was seen at many Sled Island events). This exhibition will comprise of a major new sculpture, several new paintings and a new audio piece multiple titled Gutterballs with music by Millar and vocals by the amazing Samantha Savage Smith. You won’t want to miss this exhibition. Mark your calendars! Oh Canada - Mass MoCA (Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art) May 27th, 2012 through to april 1st, 2013 Congratulations are in order to Eric Cameron, David Hoffos, Micah Lexier, Luanne Martineau, Chris Millar, Kent Monkman and Graeme Patterson on their inclusion in an upcoming exhibition at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. Curated by Denise Markonish, Oh, Canada presents work by over 60 Canadian contemporary artists. The scope of the exhibition exceeds a nationalistic tone by “… encouraging a dialogue about contemporary art made in Canada, touching on issues of craft/making, conceptualism, humour and identity…” The show will be complimented by a detailed catalogue with contributions by Douglas Coupland, Candice Hopkins, Lesley Johnstone, Wayne Baerwarldt and Louise Déry to name a few. This exhibition is definitely worth a visit should you happen to be in the area. Currently on View travel advisOry Harold Klunder – Graphic Works: The Montréal Years Eric Cameron: Exhibition extended Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada 1965-1980, group exhibition at the Art Gallery of Alberta, to August 13th, 2011 Edmonton, Alberta; on view from June 25th through to September 25th. -

Housing and Location of Young Adults, Then and Now: Consequences of Urban Restructuring in Montreal and Vancouver

HOUSING AND LOCATION OF YOUNG ADULTS, THEN AND NOW: CONSEQUENCES OF URBAN RESTRUCTURING IN MONTREAL AND VANCOUVER by MARKUS MOOS BES, The University of Waterloo, 2004 MPL, Queen’s University, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2012 © Markus Moos, 2012 Abstract Young adults, 25 to 34 years of age, decide on housing, residential location and commuting patterns in an altered context from when the same age cohort entered housing markets in the early 1980s. Neo-liberalization reduced the availability of low- cost, rental housing, and post-Fordist restructuring increased labour market inequality. Societal changes contributed to decreases in household size and delay in child bearing. This thesis asks how the contextual changes factor into young adults’ housing decisions in the Montreal and Vancouver metropolitan areas where restructuring occurred differently, and discusses implications for equity and sustainability. The young adult residential ecology is increasingly concentrated into higher density and amenity-rich neighbourhoods, particularly near transit in Vancouver. The trends are explained by shifts toward the service sector, declining real incomes and growing inter-generational wage inequalities that reduce young adults’ spending power in housing markets, especially in Vancouver with its speculative land market and wealthy immigrants. Holding other characteristics constant, young adults in Vancouver are less likely to reside in single-family dwellings than detached, row or apartment units. In Montreal the trend is toward single-family living. Commuting distances and modes are similar between Vancouver and Montreal but multiple-person households and those with children have longer and more automobile-oriented commutes in Vancouver. -

Vancouverism and Its Cultural Amenities: the View from Here Peter Dickinson

Vancouverism and Its Cultural Amenities: The View from Here Peter Dickinson Canadian Theatre Review, Volume 167, Summer 2016, pp. 40-47 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/629849 Access provided at 17 Aug 2019 01:00 GMT from Simon Fraser University FEATURES | Vancouverism and Its Cultural Amenities Vancouverism and Its Cultural Amenities: The View from Here by Peter Dickinson In this essay, I want to begin thinking through some of the very basic material (as in, bricks and mortar) links between real estate What is the relationship between the and the performing arts. What, I am asking, is the relationship between the lifestyle and design amenities we seek out as desirable lifestyle and design amenities we seek out selling features in high-priced urban condominium towers and the as desirable selling features in high-priced cultural amenities we all too easily overlook or take for granted in urban condominium towers and the cultural our cities? Let’s start by talking about chandeliers. And not just any chandeliers. Th e one I have in mind is a amenities we all too easily overlook or take giant 4 metre by 6 metre faux-crystal candelabra designed by cel- for granted in our cities? ebrated Vancouver artist Rodney Graham, which is to be installed as a public work of art underneath the Granville Street Bridge, just over Beach Avenue. Th e chandelier is meant to dangle halfway between the underside of the bridge’s northern viaduct and the street, gently rotating as it slowly ascends over the course of the day; then, at an appointed hour each day, the chandelier will sud- Howe Street, and marketed by the company as a “living sculpture” denly release, spinning rapidly as it descends to its starting point. -

The D.A.P. Catalog Fall 2020

THE D.A.P. CATALOG FALL 2020 Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 78 Journals 79 CATALOG EDITOR Previously Announced Exhibition Catalogs 80 Thomas Evans DESIGNER Martha Ormiston Fall Highlights 82 COPY WRITING Arthur Cañedo, Megan Ashley DiNoia, Thomas Evans, Emilia Copeland Titus Photography 84 Art 108 ABOVE: Architecture & Design 144 B. Wurtz, various pan paintings. From B. Wurtz: Pan Paintings, published by Hunters Point Press. See page 127. Specialty Books 162 FRONT COVER: John Baldessari, Palm Tree/Seascape, 2010. From John Baldessari, published by Walther König, Art 164 Köln. See page 61. Photography 190 BACK COVER: Feliciano Centurión, Estoy vivo, 1994. From Feliciano Centurión, published by Americas Society. Backlist Highlights 197 See page 127. Index 205 Plus sign indicates that a title is listed on Edelweiss NEED HIGHER RES Gerhard Richter: Landscape The world’s most famous painter focuses on the depiction of natural environments, from sunsets to seascapes to suburban streets Gerhard Richter’s paintings combine photorealism and abstraction in a manner that is completely unique to the German artist. A master of texture, Richter has experimented with different techniques of paint application throughout his career. His hallmark is the illusion of motion blur in his paintings, which are referenced from photographs he himself has taken, obscuring his subjects with gentle brushstrokes or the scrape of a squeegee, softening the edges of his figures to appear as though they had been captured by an unfocused lens. This publication concentrates on the theme of landscape in Richter’s work, a genre to which he has remained faithful for over 60 years, capturing environments from seascapes to countryside.