VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, Fred Herzog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color | National Gallery of Canada 2017-10-18, 7�42 AM

Donʼt Take My Kodachrome Away — A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color | National Gallery of Canada 2017-10-18, 742 AM Don’t Take My Kodachrome Away — A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color Sheila Singhal October 17, 2017 One of the things that strikes a viewer almost immediately when presented with an array of Fred Herzog’s photographs is the pop of “Kodachrome red” that appears in almost every image. Whether in the tights of a young girl and the nearby skirt of an older woman in Red Stockings (1961), or in the signage of Empty Barber Shop (1966), or in a painted billboard for Buckingham cigarettes in Elysium Cleaners (1958), Herzog includes the hue in the large majority of his photographs. “Kodachrome red, available only in slides, was his muse,” writer and critic Sarah Milroy has said, “and many of his best works are anchored in this primary hue.” Fred Herzog, Red Stockings, 1961. © Fred Herzog, Courtesy Equinox Gallery https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/books/dont-take-my-kodachrome-away-a-review-of-fred-herzog-modern-color Page 1 of 9 Donʼt Take My Kodachrome Away — A Review of Fred Herzog: Modern Color | National Gallery of Canada 2017-10-18, 742 AM In the new book, Fred Herzog: Modern Color, the photographer’s masterful use of colour is on full display. A quintessential mid-20th-century street photographer, Herzog captures daylit streets crammed with shop signs and people. At night, the neon lights of a gloriously gaudy Vancouver float in the darkness like fireflies in pitch. Open lots with wrecked and decaying automobiles sit cheek by jowl with down-at-heel businesses on forgotten street corners. -

Marian Penner Bancroft Rca Studies 1965

MARIAN PENNER BANCROFT RCA STUDIES 1965-67 UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, Arts & Science 1967-69 THE VANCOUVER SCHOOL OF ART (Emily Carr University of Art + Design) 1970-71 RYERSON POLYTECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, Toronto, Advanced Graduate Diploma 1989 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, Visual Arts Summer Intensive with Mary Kelly 1990 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, short course with Griselda Pollock SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, upcoming in May 2019 WINDWEAVEWAVE, Burnaby, BC, video installation, upcoming in May 2018 HIGASHIKAWA INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL GALLERY, Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan, Overseas Photography Award exhibition, Aki Kusumoto, curator 2017 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, RADIAL SYSTEMS photos, text and video installation 2014 THE REACH GALLERY & MUSEUM, Abbotsford, BC, By Land & Sea (prospect & refuge) 2013 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HYDROLOGIC: drawing up the clouds, photos, video and soundtape installation 2012 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, SPIRITLANDS t/Here, Grant Arnold, curator 2009 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, CHORUS, photos, video, text, sound 2008 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HUMAN NATURE: Alberta, Friesland, Suffolk, photos, text installation 2001 CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver THE MENDEL GALLERY, Saskatoon SOUTHERN ALBERTA ART GALLERY, Lethbridge, Alberta, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) 2000 GALERIE DE L'UQAM, Montreal, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver, VISIT 1999 PRESENTATION HOUSE GALLERY, North Vancouver, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) UNIVERSITY -

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol. 44 Issue 97 While the Artery is providing this newsletter as a courtesy service, every effort is made to ensure that information listed below is timely and accurate. However we are unable to guarantee the accuracy of information and functioning of all links. INDEX # ON AT THE GALLERY: Exhibition My Vintage Rubble and Fish & Moose series 1 Mini-retrospective by Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wednesday, Feb 1, 6:30 pm EVENTS AROUND TOWN EVENTS 2-6 EXHIBITIONS 7-24 THEATRE 25/26 WORKSHOPS 27-30 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS LOCAL EXHIBITIONS 31 GRANTS 32 MISCELLANEOUS 33 PUBLIC ART 34 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS NATIONAL AWARDS 35 EXHIBITIONS 36-44 FAIR 45/46 FESTIVAL 47-49 JOB CALL 50-56 CALL FOR PARTICPATION 57 PERFORMANCE 58 CONFERENCE 59 PUBLIC ART 60-63 RESIDENCY 64-69 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS INTERNATIONAL WEBSITE 70 BY COUNTRY ARGENTINA RESIDENCY 71 AUSTRIA PRIZE 72 BRAZIL RESIDENCY 73/74 CANADA RESIDENCY 75-79 FRANCE RESIDENCY 80/81 GERMANY RESIDENCY 82 ICELAND PERFORMERS 83 INDIA RESIDENCY 84 IRELAND FESTIVAL 85 ITALY FAIR 86 RESIDENCY 87-89 MACEDONIA RESIDENCY 90 MEXICO RESIDENCY 91/92 MOROCCO RESIDENCY 93 NORWAY RESIDENCY 94 PANAMA RESIDENCY 95 SPAIN RESIDENCY 96 RETREAT 97 UK RESIDENCY 98/99 USA COMPETITION 100 EXHIBITION 101 FELLOWSHIP 102 RESIDENCY 103-07 BRITANNIA ART GALLERY: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: 108 SUBMISSIONS TO THE ARTERY E-NEWSLETTER 109 VOLUNTEER RECOGNITION 110 GALLERY CONTACT INFORMATION 111 ON AT BRITANNIA ART GALLERY 1 EXHIBITIONS: February 1 - 24 My Vintage Rubble, Fish and Moose series – Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wed. -

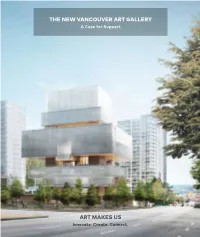

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY a Case for Support

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY A Case for Support A GATHERING PLACE for Transformative Experiences with Art Art is one of the most meaningful ways in which a community expresses itself to the world. Now in its ninth decade as a significant contributor The Gallery’s art presentations, multifaceted public to the vibrant creative life of British Columbia and programs and publication projects will reflect the Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has embarked on diversity and vitality of our community, connecting local a transformative campaign to build an innovative and ideas and stories within the global realm and fostering inspiring new art museum that will greatly enhance the exchanges between cultures. many ways in which citizens and visitors to the city can experience the amazing power of art. Its programs will touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, through remarkable, The new building will be a creative and cultural mind-opening experiences with art, and play a gathering place in the heart of Vancouver, unifying substantial role in heightening Vancouver’s reputation the crossroads of many different neighbourhoods— as a vibrant place in which to live, work and visit. Downtown, Yaletown, Gastown, Chinatown, East Vancouver—and fuelling a lively hub of activity. For many British Columbians, this will be the most important project of their Open to everyone, this will be an urban space where museum-goers and others will crisscross and encounter generation—a model of civic leadership each other daily, and stop to take pleasure in its many when individuals come together to build offerings, including exhibitions celebrating compelling a major new cultural facility for its people art from the past through to artists working today— and for generations of children to come. -

New Year's in Vancouver

NEW YEAR’S IN Activity Level: 1 VANCOUVER December 30, 2021 – 4 Days 1 Dinner Included With Salute to Vienna concert at Orpheum Fares per person: $1,470 double/twin; $1,825 single; $1,420 triple Please add 5% GST. Ring in 2022 in style and enjoy the annual performance of Salute to Vienna presented Early Bookers: $60 discount on first 15 seats; $30 on next 10 by the Vancouver Symphony. It has an Experience Points: outstanding cast of 75 musicians, singers, Earn 32 points on this tour. and dancers, and has been billed as the Redeem 32 points if you book by October 27, 2021. world’s greatest New Year’s concert. We Departure from: Victoria have reserved superb seats in the Centre Orchestra of the Orpheum Theatre. Two other shows are also included, but most theatre companies are still emerging from Covid shutdowns and planning their fall and winter schedules. A morning at the Vancouver Art Gallery is included. The tour stays 3 nights at the renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver. Salute to Vienna ITINERARY Day 1: Thursday, December 30 such as the Gateway or Granville Island Stage. Transportation is provided mid-day to the Again, if you are not interested in attending, you renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver and we stay can opt out and your fare will be reduced. We three nights. Opened in 1939 at a cost of $12 return to the hotel after the show, then at million, it was the third Hotel Vancouver and a midnight you may want to celebrate the arrival of downtown landmark with its copper green roof 2022 in the hotel lounge or nearby. -

Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’S 2016 Media Kit

Assignment: Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’s 2016 Media Kit TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 4 WHERE IN THE WORLD IS VANCOUVER? ........................................................ 4 VANCOUVER’S TIMELINE.................................................................................... 4 POLITICALLY SPEAKING .................................................................................... 8 GREEN VANCOUVER ........................................................................................... 9 HONOURING VANCOUVER ............................................................................... 11 VANCOUVER: WHO’S COMING? ...................................................................... 12 GETTING HERE ................................................................................................... 13 GETTING AROUND ............................................................................................. 16 STAY VANCOUVER ............................................................................................ 21 ACCESSIBLE VANCOUVER .............................................................................. 21 DIVERSE VANCOUVER ...................................................................................... 22 WHERE TO GO ............................................................................................................... 28 VANCOUVER NEIGHBOURHOOD STORIES ................................................... -

Reimagining Vancouver's Skid Road Through the Photography Of

“Addicts, Crooks, and Drunks”: Reimagining Vancouver’s Skid Road through the Photography of Fred Herzog, 1957–70 Tara Ng A Thesis in The Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Art History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2016 © Tara Ng, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Tara Ng Entitled: “Addicts, Crooks, and Drunks”: Reimagining Vancouver’s Skid Road through the Photography of Fred Herzog, 1957–70 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Art History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _____________________________________ Chair _____________________________________Examiner Dr. Catherine MacKenzie _____________________________________Examiner Dr. Cynthia Hammond _____________________________________Supervisor Dr. Martha Langford Approved By ______________________________ Dr. Alice Ming Wai Jim Graduate Program Director ________________2016 ______________________________ Rebecca Taylor Duclos Dean of Faculty of Fine Arts iii Abstract “Addicts, Crooks, and Drunks”: Reimagining Vancouver’s Skid Road through the Photography of Fred Herzog, 1957–70 Tara Ng This thesis explores how Canadian artist Fred Herzog’s (b. 1930) empathetic photographs of unattached, white, working-class men living on Vancouver’s Skid Road in the 1950s and 1960s contest dominant newspaper representations. Herzog’s art practice is framed as a sociologically- oriented form of flânerie yielding original, nuanced, and critical images that transcend the stereotypes of the drunk, the criminal, the old-age pensioner, and the sexual deviant on Skid Road. -

THE DIGITAL DOMAIN NO. 3: Selected Internet Visual Resources for the Study of British Columbia - Arty Photography, and Multimedia

THE DIGITAL DOMAIN NO. 3: Selected Internet Visual Resources for the Study of British Columbia - Arty Photography, and Multimedia COMPILED BY DAVID MATTISON Access Services Archivist, BC Archives, Victoria his compilation lists publicly accessible Internet image collections documenting BC's pictorial heritage in the form T of selected artwork, photographs, and multimedia (combi nations of text, still images, and audio-video) Web sites. Architecture and cartography resources will be described in a future Digital Domain. Non-image-based Internet sites such as the George Eastman House photography database are also included because they document the existence of images held by institutions. Organizations such as the Vancouver Cultural Alliance which promote access to arts resources, but do not necessarily feature reproductions from the visual arts arena, are also included. Due to space limitations and the vast amount of visual material on the Internet, this listing is not inclusive. The majority of references in this bibliography are to Web sites whose URL (Universal/Uniform Resource Locator) or Internet address always begins with http://. In order to prevent confusion and because the URL must include the service designator, the Web designator is shown. The two most popular graphical Web browsers, Microsoft Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator, both default to a Web URL when the service designator is not included. Those using the Internet through a proxy server or who have cookies disabled may encounter problems with some of these resources. You are encouraged to contact your Internet Service Provider (ISP) if you have problems connecting with a particular Web site or Internet computer system, or if you need general assistance in configuring your Web browser and any associated software required to access these resources. -

SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS of CIRCLES Through the Art of JOCK MACDONALD

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE FOR GRADES 8–11 LEARN ABOUT SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS OF CIRCLES through the art of JOCK MACDONALD Click the right corner to SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS OF CIRCLES JOCK MACDONALD through the art of return to table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 RESOURCE WHO WAS JOCK TIMELINE OF OVERVIEW MACDONALD? HISTORICAL EVENTS AND ARTIST’S LIFE PAGE 4 PAGE 8 PAGE 10 LEARNING CULMINATING HOW JOCK MACDONALD ACTIVITIES TASK MADE ART: STYLE & TECHNIQUE PAGE 11 READ ONLINE DOWNLOAD ADDITIONAL JOCK MACDONALD: JOCK MACDONALD RESOURCES LIFE & WORK IMAGE FILE BY JOYCE ZEMANS EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS OF CIRCLES through the art of JOCK MACDONALD RESOURCE OVERVIEW This teacher resource guide has been designed to complement the Art Canada Institute online art book Jock Macdonald: Life & Work by Joyce Zemans. The artworks within this guide and images required for the learning activities and culminating task can be found in the Jock Macdonald Image File provided. These activities were prepared with Laura Briscoe & Jeni Van Kesteren of Art of Math Education. Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) was one of the most radical artists in Canada in the mid-twentieth century. In the 1930s he began experimenting with abstraction, a quest that led him to many different disciplines. As author Joyce Zemans has noted, he was “guided by the most current discussions of art and aesthetics and of mathematical and scientific theories.” In the spirit of Macdonald’s works, the activities in this guide connect visual arts and mathematics. This connection will make Macdonald’s art more engaging for students and inspire a creative, personalized approach to understanding mathematical concepts of circles. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Alley Cat Rentals Artina’s (Victoria), 127 AAA Horse & Carriage Ltd. (Vancouver), 87 Artisans Courtyard (Vancouver), 82 Alliance for Arts and Culture (Courtenay), 198 Abandoned Rails Trail, 320 (Vancouver), 96 Artisan’s Studio (Nanaimo), Aberdeen Hills Golf Links Allura Direct (Whistler), 237 169 (Kamloops), 287 Alpha Dive Services (Powell Art of Man Gallery (Victoria), Abkhazi Garden (Victoria), River), 226 126 119 Alpine Rafting (Golden), 323 The Arts Club Backstage Access-Able Travel Source, 42 Alta Lake, 231 Lounge (Vancouver), 100 Accessible Journeys, 42 American Airlines, 36 Arts Club Theatre Company Active Pass (between Galiano American Automobile Asso- (Vancouver), 97 from Mayne islands), 145 ciation (AAA), 421 Asulkan Valley Trail, 320 Adam’s Fishing Charters American Express Athabasca, Mount, 399 (Victoria), 122 Calgary, 340 Athabasca Falls, 400 Adams River Salmon Run, Edmonton, 359 Athabasca Glacier, 400 286 American Foundation for the Atlantic Trap and Gill Adele Campbell Gallery Blind (AFB), 42 (Vancouver), 99 (Whistler), 236 Anahim Lake, 280 Au Bar (Vancouver), 101 Admiral House Boats Ancient Cedars area of Cougar Aurora (Banff), 396 (Sicamous), 288 Mountain, 235 Avello Spa (Whistler), 237 Adventure Zone (Blackcomb), Ancient Cedars Spa (Tofino), 236 189 Afterglow (Vancouver), 100 Anglican Church abine Mountains Recre- Agate Beach Campground, B Alert Bay, 218 ation Area, 265 258 Barkerville, 284 Backpacking, 376 Ah-Wa-Qwa-Dzas (Quadra A-1 Last Minute Golf Hot Line Backroom Vodka Bar Island), 210 (Vancouver), 88 (Edmonton), -

The Evolution of Municipal Government Arts Policy in Vancouver

kquisi'rlons 3rd Dmction des acqut:;r!ions et Bib5og;apiric Services Brm& rigs serwsces bibitwiaphrques 395 't,'ei,qI~slStas: .335. rue L%'elfrigtz>.? ~z,.*G, 0:4~.,.ln..a-.*.?. 1~rlns-t.J..&n:W: . K 1 A ~pg M 3. n ~% .cL%~15i.r * A ' ,.,,, , 2.. %.,,!:. .pa..\, .. *, i. quality of this microform is La qualitk de cette microforme heavily dependeni upon the depend grandernent de la qualite qwiity ~f the originat thesis de la th6se soilmise au submitfed for microfilming. microfiimage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualite ensure the highest quality of superieure de reproduction. reproduct ion possibk. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec I'universite degree. qui a confere le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualit4 d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser a pages were typed with a poor dbsirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont a6 university sent us an inferior dactylographiees a I'aide d'un photocopy. ruban use ou si I'universitb nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualite infkrieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, meme partielle, tk;e,, ,,, ,,,,,,m;nrninrm ,,,, ,,, is governed by de cette microforme esf soumlse the Canadian Copyright Act, a la Loi canadienne sur ie droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30,et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subsequents. THE POLITICS OF LOCAL CULTERE: THE EVOLUTION OF MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT ARTS POLICY fM VANCOUVER Susan Juliet Stevenson B.A., McGiil University 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFiLLMENT OF REQUIRmNTS FOR THE DEGREE OF OF ARTS in &he Department of Communication O Susan Stevenson SIMCIN FmSER UNIVERSITY September 1992 All rights reserved. -

Vancouver Art Gallery Announces New Members of Board of Trustees

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE VANCOUVER ART GALLERY ANNOUNCES NEW MEMBERS OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES VANCOUVER, BC (November 20, 2019) – The Vancouver Art Gallery announced at its Annual General Meeting on November 13, 2019, the appointment of three new Trustees to its Board, Leah George-Wilson, Salia Joseph and Jessica Yan-Macintosh. “Each of the new Trustees bring inspiration, experience and diversity of thought to the Vancouver Art Gallery,” said Vancouver Art Gallery Board Secretary and Chair, Governance/Nominations, Hank Bull. “These individuals are community leaders committed to the growth of the arts in Vancouver and will play a vital role in the continuing evolution of the Vancouver Art Gallery, helping lead the organization forward.” At the Annual General Meeting, Board of Trustees, Chair, David Calabrigo welcomed the new Trustees, bringing the count of voting members to 20. A complete list of the Board of Trustees can be found on the Vancouver Art Gallery website at www.vanartgallery.bc.ca/leadership. “We are truly fortunate to welcome these stellar individuals to the organization. They join a group of committed and passionate Trustees whose breadth of knowledge will help the Gallery strategically,” shared Interim Vancouver Art Gallery Director, Daina Augaitis. “Combined with their unflagging belief in the work that the Gallery does, I am confident that they will help us achieve our goals.” ABOUT THE NEW TRUSTEES Leah George-Wilson is a Chief at Tsleil Waututh Nation and was the first woman to serve this position. She is also a lawyer practicing in the area of Indigenous law at Miller Titerle + Co. George-Wilson is also the elected co-chair of the First Nations Summit, a director on the Land Advisory Board and an appointed board member of the First Nations Health Council.