1 Plaintiff, V. PURDUE PHARMA LP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bio/Pharmaceutical Outsourcing Report: November 2016

Volume 21, Number 11, November 2016 Bio/Pharmaceutical Outsourcing Report Part of PharmSource STRATEGIC ADVANTAGE Business Conditions 1 Business Conditions 1 PE-Owned Companies in Line to Change Hands PE-Owned Companies in Line to Change Hands 2 Commercial Dose Manufacturing and Mergers and acquisitions are a hot topic in the contract services industry these Packaging days, and there is a lot of curiosity about which companies are likely to change 2 New Manufacturing Deal, Temporary hands. Of course, any company is a target at any time, especially when the price is Closures and Recall for Patheon right, but insight to likely acquisition candidates can be gained by looking at the list 3 Commercial Dose Manufacturing and Packaging in Brief 3 Clinical Dose Manufacturing and leastof companies four years owned ago are by likelyprivate targets equity in (PE) the nextfirms. year On oraverage, two. PE firms tend to hold Packaging onto their investments for about five years, so companies that were acquired at 3 Marken to be Acquired by UPS The table on page 2 lists 23 CMC services companies that are PE-owned; the list 5 Clinical Dose Manufacturing and was derived from the PharmSource Strategic Advantage database “Search by Packaging in Brief Ownership” feature. It is sorted by the year each company was acquired, and 6 Side Effects: Impacts of Key Events on suggests that at least 13 CMOs and CDMOs are ripe for a transaction in the foresee- CMOs and CROs able future. 7 API — Large Molecule The sale of one company, Marken (Durham, N.C., USA), was announced just this 7 Samsung BioLogics Completes IPO month (see news item, Page 3); another, Capsugel (Morristown, N.J., USA), has been 8 API — Large Molecule in Brief mentioned in the business press as being prepared for an ownership change. -

Comparison of Oral Contraceptives and Non-Oral Alternatives

PL Detail-Document #290305 −This PL Detail-Document gives subscribers additional insight related to the Recommendations published in− PHARMACIST’S LETTER / PRESCRIBER’S LETTER March 2013 Comparison of Oral Contraceptives and Non-Oral Alternatives —More information about the use of contraceptives is available in our PL Detail-Document, Hormonal Contraception— Productsa Manufacturerb Estrogen Progestin LOW-DOSE MONOPHASIC PILLS Aviane-28 Teva EE 20 mcg Levonorgestrel 0.1 mg Falmina Novast Lessina Teva Lutera Actavis Orsythia Qualitest Sronyx Actavis Gildess Fe 1/20 Qualitest EE 20 mcg Norethindrone acetate Junel 1/20 Teva 1 mg Junel Fe 1/20 Teva Loestrin-21 1/20 Warner Chilcott/Teva Loestrin Fe 1/20 Warner Chilcott/Teva Microgestin 1/20 Actavis Microgestin Fe 1/20 Actavis Generess Fe chewable Actavis EE 25 mcg Norethindrone 0.8 mg Altavera Sandoz EE 30 mcg Levonorgestrel 0.15 mg Kurvelo Lupin Levora Actavis Marlissa Glenmark Nordette-28 Duramed/Teva Portia-28 Teva Cryselle-28 Teva EE 30 mcg Norgestrel 0.3 mg Elinest Novast Low-Ogestrel-21 Actavis Low-Ogestrel-28 Actavis Lo/Ovral-28 Wyeth Gildess Fe 1.5/30 Qualitest EE 30 mcg Norethindrone acetate Junel 1.5/30 Teva 1.5 mg Junel Fe 1.5/30 Teva Loestrin 1.5/30-21 Warner Chilcott/Teva Loestrin Fe 1.5/30 Warner Chilcott/Teva Microgestin 1.5/30 Actavis Microgestin Fe 1.5/30 Actavis More. Copyright © 2013 by Therapeutic Research Center 3120 W. March Lane, Stockton, CA 95219 ~ Phone: 209-472-2240 ~ Fax: 209-472-2249 www.PharmacistsLetter.com ~ www.PrescribersLetter.com ~ www.PharmacyTechniciansLetter.com -

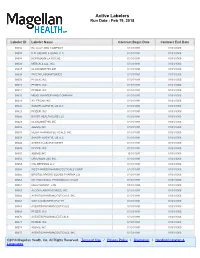

Active Labelers Run Date : Feb 19, 2018

Active Labelers Run Date : Feb 19, 2018 Labeler ID Labeler Name Contract Begin Date Contract End Date 00002 ELI LILLY AND COMPANY 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00003 E.R. SQUIBB & SONS, LLC. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00004 HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00006 MERCK & CO., INC. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00007 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00008 WYETH LABORATORIES 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00009 PFIZER, INC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00013 PFIZER, INC. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00014 PFIZER, INC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00015 MEAD JOHNSON AND COMPANY 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00023 ALLERGAN INC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00024 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00025 PFIZER, INC. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00026 BAYER HEALTHCARE LLC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00029 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00032 ABBVIE INC. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00037 MEDA PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00039 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00046 AYERST LABORATORIES 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00049 PFIZER, INC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00051 ABBVIE INC 10/01/1997 01/01/3000 00052 ORGANON USA INC. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00053 CSL BEHRING LLC 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00054 WEST-WARD PHARMACEUTICALS CORP. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00056 BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB PHARMA CO. 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00062 ORTHO MCNEIL PHARMACEUTICALS 01/01/1991 01/01/3000 00064 HEALTHPOINT, LTD. -

Pharmaceutical Company Contact Information (PDF)

Pharmaceutical Company Contact Information - Rebate Filing - as of June 2018 Labeler Name Invoice Contact Phone Extension 00002 LILLY USA, LLC LISA NORTON (317) 276-2000 00003 ER SQUIBB AND SONS INC. LYNN LEWIS (609) 897-4731 00004 GENENTECH CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION (650) 866-2666 00005 LEDERLE LABORATORIES DAN MAGUIRE (484) 563-5097 00006 MERCK & CO., INC. DOUG BICKFORD (215) 652-0671 00007 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM DAVID BUCKLEY (215) 751-5690 00008 WYETH LABORATORIES JENNIFER WOOTEN (901) 215-1883 00009 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN COMPANY/PFIZER JENNIFER WOOTEN (901) 215-1883 00013 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN COMPANY NICHOLAS CHRISTODOULOU (336) 291-1053 00014 G. D. SEARLE & CO. CINDY MCDONALD (847) 581-5726 00015 MEAD JOHNSON AND COMPANY LYNN LEWIS (609) 897-4731 00016 PHARMACIA INC. BARBARA WINGET (908) 901-7254 00023 ALLERGAN INC SHOBHANA MINAWALA (714) 246-6205 00024 SANOFI WINTHROP PHARMACEUTICALS LAURIE DUNLAP, ADMIN., GOVT. OPERATIONS (212) 551-4198 00025 PHARMACIA CORPORATION NICHOLAS CHRISTODOULOU (336) 291-1053 00026 BAYER CORPORATION PHARMACEUTICAL DIV. LINDA WOLCHESKI (203) 812-6372 00028 NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS (862) 778-8094 00029 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM DAVID BUCKLEY (215) 751-5690 00031 A. H. ROBINS COMPANY DAN MAGUIRE (610) 902-3222 00032 SOLVAY PHARMACEUTICALS STACEY LENOX (847) 937-3979 00033 SYNTEX LABORATORIES, INC. JANICE BRENNAN (973) 562-3494 00034 THE PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY JUNE STOWE (203) 899-8035 00037 CARTER-WALLACE, INC. JAY R BRENNAN (609) 655-6163 00038 ASTRAZENECA LP DAVID WRIGHT (302) 886-2268 7820 00039 AVENTIS PHARMACEUTICALS (908) 981-7461 00043 NOVARTIS CONSUMER HEALTH, INC. EDWARD D. COLLINS (973) 781-6191 00044 KNOLL LABORATORIES DEBRA DEYOUNG (847) 937-4372 00045 MCNEIL PHARMACEUTICAL (908) 218-6777 00046 AYERST LABORATORIES (901) 215-1473 00047 WARNER CHILCOTT LABORATORIES LISA KAROLCHYK (973) 442-3262 00048 KNOLL PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY DEBRA DEYOUNG (847) 937-4372 00049 ROERIG NICHOLAS CHRISTODOULOU (336) 291-1053 00051 UNIMED PHARMACEUTICALS, INC STACY LENOX (847) 937-3979 00052 ORGANON, USA, INC. -

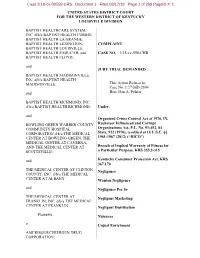

United States District Court for the Western District of Kentucky Louisville Division

Case 3:18-cv-00558-CRS Document 1 Filed 08/17/18 Page 1 of 299 PageID #: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY LOUISVILLE DIVISION BAPTIST HEALTHCARE SYSTEM, INC. d/b/a BAPTIST HEALTH CORBIN, BAPTIST HEALTH LA GRANGE, BAPTIST HEALTH LEXINGTON, COMPLAINT BAPTIST HEALTH LOUISVILLE, BAPTIST HEALTH PADUCAH, and CASE NO. _______________________3:18-cv-558-CHB BAPTIST HEALTH FLOYD; and JURY TRIAL DEMANDED BAPTIST HEALTH MADISONVILLE, INC. d/b/a BAPTIST HEALTH MADISONVILLE; This Action Relates to: Case No. 1:17-MD-2804 and Hon. Dan A. Polster BAPTIST HEALTH RICHMOND, INC. d/b/a BAPTIST HEALTH RICHMOND; Under: and Organized Crime Control Act of 1970, IX, BOWLING GREEN WARREN COUNTY Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt COMMUNITY HOSPITAL Organizations Act, P.L. No. 91-452, 84 CORPORATION d/b/a THE MEDICAL State. 922 (1970), (codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ CENTER AT BOWLING GREEN, THE 1961-1967 (2012) (“RICO”) MEDICAL CENTER AT CAVERNA, AND THE MEDICAL CENTER AT Breach of Implied Warranty of Fitness for SCOTTSVILLE; a Particular Purpose, KRS 355.2-315 and Kentucky Consumer Protection Act, KRS 367.170 THE MEDICAL CENTER AT CLINTON Negligence COUNTY, INC. d/b/a THE MEDICAL CENTER AT ALBANY Wanton Negligence and Negligence Per Se THE MEDICAL CENTER AT Negligent Marketing FRANKLIN, INC. d/b/a THE MEDICAL CENTER AT FRANKLIN Negligent Distribution Plaintiffs, Nuisance v. Unjust Enrichment AMERISOURCEBERGEN DRUG CORPORATION; Case 3:18-cv-00558-CRS Document 1 Filed 08/17/18 Page 2 of 299 PageID #: 2 CARDINAL HEALTH, INC.; MCKESSON CORPORATION; PURDUE PHARMA L.P.; PURDUE PHARMA, INC.; THE PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY, INC.; TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES, LTD.; TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC.; CEPHALON, INC.; JOHNSON & JOHNSON; JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; ORTHO-MCNEIL-JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

05/09/2016 Provider Subsystem Healthcare and Family Services Run Time: 04:25:50 Report Id 2794D052 Page: 01

MEDICAID SYSTEM (MMIS) ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF RUN DATE: 05/09/2016 PROVIDER SUBSYSTEM HEALTHCARE AND FAMILY SERVICES RUN TIME: 04:25:50 REPORT ID 2794D052 PAGE: 01 ALPHA COMPLETE LIST OF PHARMACEUTICAL LABELERS WITH SIGNED REBATE AGREEMENTS IN EFFECT AS OF 07/01/2016 NDC NDC PREFIX LABELER NAME PREFIX LABELER NAME 68782 (OSI) EYETECH 55513 AMGEN USA 00074 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 58406 AMGEN/IMMUNEX 68817 ABRAXIS BIOSCIENCE, LLC 53746 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS 16729 ACCORD HEALTHCARE INCORPORATED 65162 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS LLC 42192 ACELLA PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 69238 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 10144 ACORDA THERAPEUTICS, INC. 53150 AMNEAL-AGILA, LLC 00472 ACTAVIS 00548 AMPHASTAR PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 00228 ACTAVIS ELIZABETH LLC 69918 AMRING PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 45963 ACTAVIS INC. 66780 AMYLIN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 46987 ACTAVIS KADIAN LLC 55724 ANACOR PHARMACEUTICALS 49687 ACTAVIS KADIAN LLC 10370 ANCHEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 14550 ACTAVIS PHARMA MFGING PRIVATE LIMITED 43595 ANGELINI PHARMA, INC. 61874 ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC. 62559 ANIP ACQUISITION COMPANY 67767 ACTAVIS SOUTH ATLANTIC 54436 ANTARES PHARMA, INC. 66215 ACTELION PHARMACEUTICALS U.S., INC. 52609 APO-PHARMA USA, INC. 52244 ACTIENT PHARMACEUTICALS 60505 APOTEX CORP. 75989 ACTON PHARMACEUTICALS 63323 APP PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC. 69547 ADAPT PHARMA INC. 43485 APRECIA PHARMACEUTICALS COMPANY 76431 AEGERION PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 42865 APTALIS PHARMA US, INC 50102 AFAXYS, INC. 58914 APTALIS PHARMA US, INC. 10572 AFFORDABLE PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 13310 AR SCIENTIFIC, INC. 27241 AJANTA PHARMA LIMITED 08221 ARBOR PHARM IRELAND LIMITED 17478 AKORN INC 60631 ARBOR PHARMACEUTICALS IRELAND LIMITED 24090 AKRIMAX PHARMACEUTICALS LLC 24338 ARBOR PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 68220 ALAVEN PHARMACEUTICAL, LLC 59923 AREVA PHARMACEUTICALS 00065 ALCON LABORATORIES, INC. 76189 ARIAD PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 00998 ALCON LABORATORIES, INC. 24486 ARISTOS PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

Strayhorn V. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc

Case 2:11-cv-02058-STA-cgc Document 112 Filed 08/08/12 Page 1 of 22 PageID 2694 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE WESTERN DIVISION ______________________________________________________________________________ GLORIA STRAYHORN and JEREMY ) STRAYHORN, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) No. 11-2058-STA-cgc ) WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; ) WYETH LLC; WYETH, INC.; PFIZER, ) INC.; SCHWARZ PHARMA, INC.; ) SCHWARZ PHARMA AG; UCB GmbH; ) ALAVEN PHARMACEUTICALS LLC; ) and ACTAVIS ELIZABETH LLC, ) ) Defendants. ) ______________________________________________________________________________ SARAH SPEED, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 11-2095-STA-cgc ) WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; ) WYETH LLC; WYETH, INC.; PFIZER, ) INC.; SCHWARZ PHARMA, INC.; and ) WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ) ) Defendants. ) ______________________________________________________________________________ KATHLEEN SIMMONS, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 11-2083-STA-cgc ) WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; ) 1 Case 2:11-cv-02058-STA-cgc Document 112 Filed 08/08/12 Page 2 of 22 PageID 2695 WYETH LLC; WYETH, INC.; PFIZER, ) INC.; SCHWARZ PHARMA, INC.; ) ALAVEN PHARMACEUTICAL, LLC; ) and WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ) ) Defendants. ) ______________________________________________________________________________ GORDON and JUDITH WEAVER; ) SHENA JOHNSON; DEAN BROWN; ) GWENDOLYN RUFF; EMMA ) KETRON; LARRY HUDSON; ANNA ) ODOM; MARILYN MONCIER; ) THELMA DONALD; NETTER ) GRIGGS; ORVIELL RHODES; SELMA ) CARTER; and GERTIE KING, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) No. 11-2134-STA-cgc ) -

Lou Schmukler of BMS on Creating Supply Chain Excellence

The Official Magazine of ISPE September-October 2016 | Volume 36, Number 5 Lou Schmukler of BMS on Creating Supply Chain Excellence How to Fight a Bully: An Interview with Nicole Pierson Meet Your 2016-2017 Board of Directors Quarterly Report: BIOTECHNOLOGY www.PharmaceuticalEngineering.org Pharmaceutical Engineering | September-October 2016 | 1 WHY WE DO IT CLEAN AIR MATTERS camfilapc.com/cleanairmatters Farr Gold Series® Camtain Dust Collector Quad Pulse Package Dust Collector Dust, Mist and Fume Collectors AIR POLLUTION CONTROL www.camfilapc.com • e-mail: [email protected] • 855-405-2271 CHANGE IS OPPORTUNITY Some see change as a problem; we see change as an opportunity. Adapting to the evolving trends and ever- changing regulations in the life sciences industry is what we’re known for. We’re driven to find the right solution to the most technically challenging problems. And we’re satisfied only when we’ve produced results that make you successful. crbusa.com THE RELENTLESS PURSUIT OF SUCCESS. YOURS .™ Biological Animal Health OSD Blood Fractionation Fill/Finish Oligonucleo/Peptides Vaccines Medical Devices API’s Nutraceuticals Engineering | Architecture | Construction | Consulting Editor’s Voice A First Time for Everything My introduction to the world of biopharma occurred in June 2015 as I listened to Andy Skibo, then Chair of ISPE’s Board, deliver his “Biologics Supply Chain Risks” keynote address at the ISPE/FDA/PQRI Editorial Board Quality Manufacturing Conference in Washington, DC. He emphasized the potential effect of supply Editor in chief: Anna Maria di Giorgio chain risk on biologics, which are projected to account for 80% of the pipeline and 70% of sales revenue Managing editor: Amy Loerch by 2020—just three short years away. -

The State of Utah V. APOTEX CORPORATION

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Court of Appeals Briefs 2010 The tS ate of Utah v. APOTEX CORPORATION; BAXTER HEALTHCARE CORPORATION; BOEHRINGERINGELHEIM CORPORATION; MALLINCKRODT INC.; CSL BEHRING; FOREST ABORATORIES, INC.; MORTON GROVE PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; MUTUAL PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY, INC.; NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS CORPORATION; OTSUKA AMERICA, INC.; PFIZER, INC.; QUALITEST PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; SCHERING- PLOUGH CORPORATION; SCHWARZ Recommended Citation Reply Brief, Utah v. Apotex Corporation, No. 20100257 (Utah Court of Appeals, 2010). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca3/2258 This Reply Brief is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Court of Appeals Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. PHARMA USA HOLDINGS, INC; TARO PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC.; UPSHER- SMITH, INC.; and WYETH, INC. : Reply Brief Utah Court of Appeals Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca3 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief Submitted to the Utah Court of Appeals; digitized by the Howard W. Hunter Law Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OCR, may contain errors. R. James DeRose III; Locke, Lord, Bissell and Liddell; Counsel for Appellees. Joseph W. Steele; David C. Biggs; Steele and Biggs; Special Assistant Attorneys General; Counsel for Appellant. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF UTAH THE STATE OF UTAH, Plaintiff/Appellant, vs. -

Medical, Surgical & Pharmaceutical Purchasing Program

13MS6992 AAO Formulary FC_BC_Layout 1 5/14/13 12:04 PM Page 1 13MS6992 Medical, Surgical & Pharmaceutical Purchasing Program Over 90,000 items in stock No purchase commitments No enrollment fee Over 300 NEW PRODUCTS To Order: 1-800-P-SCHEIN (1-800-772-4346) 8am–9pm (et) To Fax: 1-800-329-9109 24 Hours JOIN OUR COMMUNITY www.henryschein.com/aao 13MS6992 AAO Formulary Ads_Formulary 5/15/13 2:54 PM Page 2 With , access a comprehensive portfolio of products and services to help your ophthalmology practice thrive. Purchasing Program Formulary Assembled precisely with your needs in mind, this Purchasing Program includes popular and essential products for a successful Eye MD practice. Leveraging the combined purchasing volume of Program members, the formulary delivers savings on a variety of products. If you are currently ordering online, you can receive additional benefits through our loyalty program exclusively for Academy members. www.henryschein.com/aao Ordering, Tracking, and Spend Management Tools Henry Schein’s Web site is tailored to the needs of your practice and the conditions you treat. The enhanced search capabilities and functionality make finding, ordering, and tracking products quick and efficient. Spend reporting tools allow you to analyze and optimize your budget. www.henryschein.com/medical Consultation Services Looking for solutions that improve patient safety and practice performance? Consider our OSHA compliance checklist. Are you looking to upgrade, move, or add services to your current practice? Henry Schein Sales Consultants can help you navigate complex challenges and select the solutions that are right for you at no additional charge. -

Cough and Cold Drugs

Page 1 of 3 Cough and Cold Drugs Per Section 1927(d) of the Social Security Act, agents used for the symptomatic relief of cough and colds are optional for coverage by Medicaid and are exempt from coverage under the Medicare Modernization Act. The following excluded drugs [per Section 1927(d)] are covered by Arkansas Medicaid. This reference list includes drugs covered for Arkansas Medicaid beneficiaries and dual eligible Medicare/Arkansas Medicaid beneficiaries. Cough and Cold products are restricted to beneficiaries under the age of 21 and to beneficiaries with Long Term Care Coverage. OTC Cough and Cold Medications in this list are only covered pursuant to a valid prescription but are not covered for Long Term Care beneficiaries. Inclusion on this list does not guarantee market availability and products must have a rebate agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to be covered by Arkansas Medicaid. Pharmacy Quantity of Claim Edits may apply. Arkansas Medicaid Pharmacy Claim Edits Pharmacy Prior Authorization or Clinical Criteria may apply. Arkansas Medicaid Pharmacy Prior Authorization Criteria The Labeler Code and Label Name are supplied for provider reference. For questions about a specific NDC or for further information, please call the AR Pharmacy Help Desk at TOLL FREE (800) 424-7895. Updated 06/21/2019 LABELER CODE DRUG STRENGTH DOSE FORM ROUTE LABEL NAME MANUFACTURER 67877 BENZONATATE 100 MG CAPSULE ORAL BENZONATATE 100 MG CAPSULE ASCEND LABS 68084 BENZONATATE 100 MG CAPSULE ORAL BENZONATATE 100 MG -

Medical, Surgical & Pharmaceutical Purchasing Program

10MS3123 Medical, Surgical & Pharmaceutical Purchasing Program • Over 90,000 items in stock • No purchase commitments • No enrollment fee • Over 150 price reductions • Contract pricing for over 140 items www.henryschein.com/AAO Privileges Rewards Buy what you need, get what you want Earn reward points with PRIVILEGES while saving money with Henry Schein Brand Products. With our PRIVILEGES PROGRAM, we believe in rewarding our loyal customers with products and services that will help their practices stay competitive and profitable, now more than ever. Henry Schein Brand Products provide brand quality and performance without brand cost. As a PRIVILEGES member, you’ll receive: Visit your account often to check your points, browse the gift • PRIVILEGES Rewards points for all electronic purchases catalog and redeem for thousands of brand-name gift items – including FREE travel and event tickets! You can reward an • Value Certificates to reduce your expenses and offer employee or redecorate your office with PRIVILEGES points! you the opportunity to earn Bonus Points Sign up now to start enjoying all the special attention and • PRIVILEGES Monthly E-Promotions exclusive benefits that you deserve. Membership is FREE! • Exclusive Quarterly E-Newsletters To enroll or learn more, speak with your Sales Consultant • Access to Practice Marketing Services or visit www.henryschein.com/privilegesmd • Double points program for Privileges I Allscripts I Henry Schein Brand I Rx Samples Service I Henry Schein Financial Services 1.866.MED.VIPS 1.800.PSCHEIN www.henryschein.com/privilegesmd www.henryschein.com/medical [email protected] ©2010 Henry Schein, Inc. No copying without permission. Not responsible for typographical errors.