Sir James Dewar, 1842-1923

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science. -

December 4, 1954 NATURE 1037

No. 4440 December 4, 1954 NATURE 1037 COPLEY MEDALLISTS, 1915-54 is that he never ventured far into interpretation or 1915 I. P. Pavlov 1934 Prof. J. S. Haldane prediction after his early studies in fungi. Here his 1916 Sir James Dewar 1935 Prof. C. T. R. Wilson interpretation was unfortunate in that he tied' the 1917 Emile Roux 1936 Sir Arthur Evans word sex to the property of incompatibility and 1918 H. A. Lorentz 1937 Sir Henry Dale thereby led his successors astray right down to the 1919 M. Bayliss W. 1938 Prof. Niels Bohr present day. In a sense the style of his work is best 1920 H. T. Brown 1939 Prof. T. H. Morgan 1921 Sir Joseph Larmor 1940 Prof. P. Langevin represented by his diagrams of Datura chromosomes 1922 Lord Rutherford 1941 Sir Thomas Lewis as packets. These diagrams were useful in a popular 1923 Sir Horace Lamb 1942 Sir Robert Robinson sense so long as one did not take them too seriously. 1924 Sir Edward Sharpey- 1943 Sir Joseph Bancroft Unfortunately, it seems that Blakeslee did take them Schafer 1944 Sir Geoffrey Taylor seriously. To him they were the real and final thing. 1925 A. Einstein 1945 Dr. 0. T. Avery By his alertness and ingenuity and his practical 1926 Sir Frederick Gow 1946 Dr. E. D. Adrian sense in organizing the Station for Experimental land Hopkins 1947 Prof. G. H. Hardy Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor (where he worked 1927 Sir Charles Sherring- 1948 . A. V. Hill Prof in 1942), ton 1949 Prof. G. -

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA of SCIENCE and OTHER WRITINGS the Rockefeller Institute Press

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA OF SCIENCE AND OTHER WRITINGS The Rockefeller Institute Press IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK 1960 @ 1960 BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 60-13207 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE The Ethical Dilemma of Science Living mechanism 5 The present tendencies and the future compass of physiological science 7 Experiments on frogs and men 24 Scepticism and faith 39 Science, national and international, and the basis of co-operation 45 The use and misuse of science in government 57 Science in Parliament 67 The ethical dilemma of science 72 Science and witchcraft, or, the nature of a university 90 CHAPTER TWO Trailing One's Coat Enemies of knowledge 105 The University of London Council for Psychical Investigation 118 "Hypothecate" versus "Assume" 120 Pharmacy and Medicines Bill (House of Commons) 121 The social sciences 12 5 The useful guinea-pig 127 The Pure Politician 129 Mugwumps 131 The Communists' new weapon- germ warfare 132 Independence in publication 135 ~ CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE About People Bertram Hopkinson 1 39 Hartley Lupton 142 Willem Einthoven 144 The Donnan-Hill Effect (The Mystery of Life) 148 F. W. Lamb 156 Another Englishman's "Thank you" 159 Ivan P. Pavlov 160 E. D. Adrian in the Chair of Physiology at Cambridge 165 Louis Lapicque 168 E. J. Allen 171 William Hartree 173 R. H. Fowler 179 Joseph Barcroft 180 Sir Henry Dale, the Chairman of the Science Committee of the British Council 184 August Krogh 187 Otto Meyerhof 192 Hans Sloane 195 On A. -

How Liquid Helium and Superconductivity Came to Us

IEEE/CSC & ESAS EUROPEAN SUPERCONDUCTIVITY NEWS FORUM (ESNF), No. 16, April 2011 Heike Kamerlingh Onnes and the Road to Liquid Helium Dirk van Delft, Museum Boerhaave – Leiden University e-mail: [email protected] Abstract – I sketch here the scientific biography of Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who in 1908 was the first to liquefy helium and in 1911 discovered superconductivity. A son of a factory owner, he grew familiar with industrial approaches, which he adopted and implemented in his scientific career. This, together with a great talent for physics, solid education in the modern sense (unifying experiment and theory) proved indispensable for his ultimate successes. Received April 11, 2011; accepted in final form April 19, 2011. Reference No. RN19, Category 11. Keywords – Heike Kamerligh Onnes, helium, liquefaction, scientific biography I. INTRODUCTION This paper is based on my talk about Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (HKO) and his cryogenic laboratory, which I gave in Leiden at the Symposium “Hundred Years of Superconductivity”, held on April 8th, 2011, the centennial anniversary of the discovery. Figure 1 is a painting of HKO from 1905, by his brother Menso, while Figure 2 shows his historically first helium liquefier, now on display in Museum Boerhaave of Leiden University. Fig. 1. Heike Kamerling Onnes (HKO), 1905 painting by his brother Menso. 1 IEEE/CSC & ESAS EUROPEAN SUPERCONDUCTIVITY NEWS FORUM (ESNF), No. 16, April 2011 Fig. 2. HKO’s historical helium liquefier (last stage), now in Museum Boerhaave, Leiden. I will address HKO’s formative years, his scientific mission, the buiding up of a cryogenic laboratory as a direct consequence of this mission, add some words about the famous Leiden school of instrument makers, the role of the Leiden physics laboratory as an international centre of low temperature research, to end with a conclusion. -

The Royal Society of Chemistry Presidents 1841 T0 2021

The Presidents of the Chemical Society & Royal Society of Chemistry (1841–2024) Contents Introduction 04 Chemical Society Presidents (1841–1980) 07 Royal Society of Chemistry Presidents (1980–2024) 34 Researching Past Presidents 45 Presidents by Date 47 Cover images (left to right): Professor Thomas Graham; Sir Ewart Ray Herbert Jones; Professor Lesley Yellowlees; The President’s Badge of Office Introduction On Tuesday 23 February 1841, a meeting was convened by Robert Warington that resolved to form a society of members interested in the advancement of chemistry. On 30 March, the 77 men who’d already leant their support met at what would be the Chemical Society’s first official meeting; at that meeting, Thomas Graham was unanimously elected to be the Society’s first president. The other main decision made at the 30 March meeting was on the system by which the Chemical Society would be organised: “That the ordinary members shall elect out of their own body, by ballot, a President, four Vice-Presidents, a Treasurer, two Secretaries, and a Council of twelve, four of Introduction whom may be non-resident, by whom the business of the Society shall be conducted.” At the first Annual General Meeting the following year, in March 1842, the Bye Laws were formally enshrined, and the ‘Duty of the President’ was stated: “To preside at all Meetings of the Society and Council. To take the Chair at all ordinary Meetings of the Society, at eight o’clock precisely, and to regulate the order of the proceedings. A Member shall not be eligible as President of the Society for more than two years in succession, but shall be re-eligible after the lapse of one year.” Little has changed in the way presidents are elected; they still have to be a member of the Society and are elected by other members. -

Sir William Crookes (1832-1919) Published on Behalf of the New Zealand Institute of Chemistry in January, April, July and October

ISSN 0110-5566 Volume 82, No.2, April 2018 Realising the hydrogen economy: economically viable catalysts for hydrogen production From South America to Willy Wonka – a brief outline of the production and composition of chocolate A day in the life of an outreach student Ngaio Marsh’s murderous chemistry Some unremembered chemists: Sir William Crookes (1832-1919) Published on behalf of the New Zealand Institute of Chemistry in January, April, July and October. The New Zealand Institute of Chemistry Publisher Incorporated Rebecca Hurrell PO Box 13798 Email: [email protected] Johnsonville Wellington 6440 Advertising Sales Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Printed by Graphic Press Editor Dr Catherine Nicholson Disclaimer C/- BRANZ, Private Bag 50 908 The views and opinions expressed in Chemistry in New Zealand are those of the individual authors and are Porirua 5240 not necessarily those of the publisher, the Editorial Phone: 04 238 1329 Board or the New Zealand Institute of Chemistry. Mobile: 027 348 7528 Whilst the publisher has taken every precaution to ensure the total accuracy of material contained in Email: [email protected] Chemistry in New Zealand, no responsibility for errors or omissions will be accepted. Consulting Editor Copyright Emeritus Professor Brian Halton The contents of Chemistry in New Zealand are subject School of Chemical and Physical Sciences to copyright and must not be reproduced in any Victoria University of Wellington form, wholly or in part, without the permission -

James Dewar-More Than a Flask

Educator Indian Journal of Chemical Technology Vo l. I 0. July 2003, pp. 424-434 James Dewar-More than a flask Jaime Wi sniak Department of Chemical Engineering, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel 841 05 James Dewar (1842-1923) is widely known for his pioneering work i.n cryogenics, of being the first to achieve the liquefaction of hydrogen, by the flask that carries his name, and by his studies about the behaviour of living organisms and materials under conditions of extreme cold. Although he was an excellent experimentalist, he did not leave many significant theoretical contributions. 12 Life and career ' James Dewar (Fig. I) was born on September 20, 1842, in Kinkardine-on-Forth, Scotland, the youngest of seven sons of Thomas Dewar and Ann Eadie Dewar. When he was ten years old he went skating and fell through ice in a frozen lake and when rescued walked about in hi s wet clothes until they were dry so that his family would not know about his accident. As a result he contracted rheumatic fever, which crippled him; he had to go on crutches for a couple of years and was left with a damaged heart. During this period he was in much contact with the village carpenter and practiced his hands in making violins. He always regarded th e training he thus received as the most important part of hi s education and the foundation of the great manual dexterity, which he displayed in hi s 1 work and hi s lectures • By the time he was fifteen he had lost both parents and went to li ve with one of hi s brothers who owned a drapery shop in Kincardaine. -

Sir James Dewar, 1842-1923: a Ruthless Chemist, J

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 38, Number 1 (2013) 79 copy of his sumptuous, illustrated first Leiden edition remember that it was only near the end of the eighteenth of 1732. In this chapter, Powers does briefly discuss the century that Lavoisier provided a useful definition of the fact that Boerhaave does not mention Stahl’s phlogiston term “chemical element.” theory anywhere in his Elementa Chemiae. He notes that Professor Powers’ book is a concise work, dense Boerhaave’s pabulum ignis, compared by some modern with information, yet highly accessible for historians day scholars to phlogiston, was presented as “the mate- and non-historians alike. In each of seven chapters, fol- rial cause of inflammability… needed to interact with lowed by a section titled CONCLUSION (“Boerhaave’s instrumental fire… for combustion to occur.” Stahl’s Legacy”), the author provides an outline at the start and phlogiston, by contrast, was considered to be the very a brief, helpful wrap up at the conclusion. There are 30 substance of fire “fixed” in an inflammable body. The pages of Notes, nicely indexed both to chapter and also final chapter (“From Alchemy to Chemistry”) describes in the running header to pages. This is followed by a Boerhaave’s investigations and teachings over three 21-page bibliography and an adequate index that oc- decades of the mercurialist theory of chemistry. Essen- casionally misses important specifics- for example, le tially the concept that all metals shared a rarified form of Fèvre and Glaser are important chemists, discussed in mercury gave some theoretical support to the possibility the body of the book, but missing in the index. -

A History of the National Bureau of Standards

FOUNDING THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS (1901-10) CHAPTER II SAMUEL WESLEY STRATTON For much of its first decade and a half, until shortly before America's entry into World War I, the Bureau's energies were almost wholly engaged in developing its staff and organization, establishing new and much needed standards for science and industry, and proving itself as a valuable adjunct of Government and industry. It assumed responsibilities as readily as it accepted those thrust upon it, and found them proliferating at a rate faster than the Bureau could grow. In 1914, making its first pause to take stock, the Bureau discovered that it had virtually to rewrite the functions of the organic act that had created it. This is the story told in the next two chapters. From the day he arrived in Washington, Samuel Wesley Stratton (1861—1931) was the driving force behind the shaping of the National Bureau of Standards. Louis A. Fischer and Dr. Frank A. Wolff, Jr., who had been with the Office of Weights and Measures since 1880 and 1897, respectively, and had friends and acquaintances who knew many members of Congress, did much of the work of bringing the proposed bill to the favorable attention of members in both Houses. But it was Stratton, enlisting the aid of other scientists and officials in the Government, who drafted the text of Sec. retary Gage's letter, prepared the arguments that were to persuade Congress, and secured the imposing and unprecedented array of endorsements for the proposed laboratory.' At his very first meeting on Capitol Hill, Stratton "mesmerized the House Committee," Wolff recalled, "and splendid hearings were held which were printed for distribution without stint." 2 He was to be the director of the Bureau for the next 21 years. -

Superconductivity APS Lecture

Superconductivity: Anatomy of a Discovery Peter Pesic St. John’s College, Santa Fe, NM with thanks to the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Cryogenics timeline 1832 Michael Faraday liquefies chlorine 1869 Thomas Andrews measures isotherms of CO2 (critical point) 1873 J. D. Van der Waals: (p + a/v2)(v - b) = RT 1877 Louis Cailletet and Raoul Pictet obtain very small droplets of liquid oxygen 1880 Van der Waals: principle of equivalent states 1883 Szygmunt Wroblewsky and Karol Olszewski liquefy oxygen 1895 William Ramsey discovers terrestrial helium 1896 Hampson and Linde obtain patents for liquid air cycle 1898 James Dewar liquefies hydrogen 1908 Heike Kamerlingh Onnes liquefies helium 1911 Onnes and associates discover superconductivity Michael Faraday’s apparatus for the liquefaction of chlorine (1832) Louis Cailletet’s apparatus for the liquefaction of gases Raoul Pictet’s method for the liquefaction of oxygen (1877) The liquefaction of oxygen by Raoul Pictet (1877) Cryogenics timeline 1832 Michael Faraday liquefies chlorine 1869 Thomas Andrews measures isotherms of CO2 (critical point) 1873 J. D. Van der Waals: (p + a/v2)(v - b) = RT 1877 Louis Cailletet and Raoul Pictet obtain very small droplets of liquid oxygen 1880 Van der Waals: principle of equivalent states 1883 Szygmunt Wroblewsky and Karol Olszewski liquefy oxygen 1895 William Ramsey discovers terrestrial helium 1896 Hampson and Linde obtain patents for liquid air cycle 1898 James Dewar liquefies hydrogen 1908 Heike Kamerlingh Onnes liquefies helium 1911 Onnes and associates discover superconductivity “A Friday Evening Discourse at the Royal Institution: Sir James Dewar on Liquid Hydrogen, 1904,” by Henry Jamyn Brooks (Royal Institution) Sir James Dewar and his famous flask Don’t be irascible. -

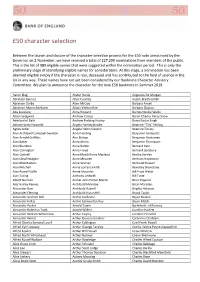

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner