App for Serum Phosphate Control: a Randomized Controlled Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portrait of an Academic Hospital the French Version of the Community Report Is Available at Rapportannuel.Hopitalmontfort.Com

MONTFORT 101: Portrait of an Academic Hospital The french version of the community report is available at rapportannuel.hopitalmontfort.com Hôpital Montfort June 2016 Message from the leadership team The year 2015-2016 was a turning point in Montfort’s evolution as an academic hospital. Intense reflection, nourished by the experiences and accomplishments of our 2011-2015 strategic plan led to the development of a new strategy. Therefore, it is with great pleasure that we present you with the Hôpital Montfort 2016-2021 Strategy: Mission Hôpital Montfort is Ontario’s Francophone Academic Hospital, offering exemplary person-centred care. Vision Your hospital of reference for outstanding services, designed with and for you. Values Our daily actions are guided by compassion, excellence, respect, accountability and mutual support. Our 2016–2021 strategy is based on four major objectives. Over the next five years, through the work of the entire Montfort Team, these objectives will translate into results with a positive impact on our community. Our objectives are: • To enhance targeted clinical services • To become a clinical centre of excellence in multimorbidity • To achieve the attributes of an academic hospital • To fulfill our provincial mandate Our new mission and its accompanying strategy will expand Montfort’s role as an academic hospital. This designation was conferred in June 2013, and the impact of this new status is felt each day with growing intensity. We are often asked: What does it change for Montfort to be an academic hospital? The answer is simple: an academic hospital stands out for the exemplary care it offers its patients, thepractical teaching it provides for the next generation of healthcare professionals, and the research it conducts to advance knowledge in health and medicine. -

Ottawa Quality and Patient Safety Conference

2019 Ottawa Patient Safety Conference Hosted by The Ottawa Hospital IQ@TOH Overview The Ottawa Hospital and IQ@TOH are proud to present the 2019 Ottawa Patient Safety Conference on November 1. The conference is an opportunity to share and learn about relevant practices to improve the quality and safety of care. This year’s theme is: “How Education Can Drive Innovation to Enhance Patient Safety” Our speakers will include prominent leaders in the field of patient safety, technology, education and innovation. Audience members will hear from keynote speakers are Dr. Brian Hodges and Dr. Marcia Clark, as well as a panel of experts. The conference is open to health care professionals, managers, administrators and academics. This forum will provide both presenters and registrants with a valuable opportunity to share innovative practices from diverse perspectives to: • Identify barriers and facilitators in the current health care environment for promoting patient safety • Integrate different perspectives to co-create educational solutions for patient safety • Propose educational solutions for improving patient safety within your context Planning Committee Dr. Alan Forster (Chair), Dr. Jerry Maniate, Samantha Hamilton (Conference Director), Leanne Bulsink (Conference Coordinator), Dr. Glen Posner, Dr. Lynn Ashdown, Dr. Eric Wooltorton, Thomas Hayes, Tracy Wrong, Melissa Brett, Lisa Freeman, David Molson, Venessa Goulet, Brooke Peloquin Catherine Foglietta. 1 Ottawa Quality & Patient Safety Conference Facilitated Interactive Session New to the conference this year is an interactive session where expert facilitators will assist attendees in sharing ideas and creating recommendations on how education can be enhanced to improve patient safety in Canada. After the conference, a consolidated summary of the recommendations will be created and shared with attendees. -

Planning Your Scheduled Cesarean Birth

Planning Your Scheduled Cesarean Birth THE OTTAWA HOSPITAL CP18 D (12/2013) Disclaimer This is general information developed by The Ottawa Hospital. It is not intended to replace the advice of a qualified health-care provider. Please consult your health-care provider who will be able to determine the appropriateness of the information for your specific situation. All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be produced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the written permission of The Ottawa Hospital, Clinical Pathway Project Team. © The Ottawa Hospital, December, 2013. Table of Contents Checklist: Evening before surgeryy . 2 Eating and Drinking Instructions . 3 The Day of Surgery In the morning before coming to the hospital . 3 Coming to the hospital . 5 At the hospital . 5 In the Operating Room (OR). 6 Preparing you for the operation and your baby’s birth . 6 In the Recovery Room (PACU) Family Presence . 7 Your Nursing Care . 8 Exercises . 9 On the Mother Baby Unit . 9 Civic Campus Map – 4th Floorr . 10 General Campus Map – 8th Floorr. 11 Birthing Unit Cesarean Birth Patient Handout My surgery will be on __________________________ at ________________ hr at The Ottawa Hospital _______________________________________ Campus Time of arrival to hospital: ____________________________________________ D Civic Campus D General Campus Finding out the time of surgery: Finding out the time of surgery: We will call you the day/evening We will call you day/evening before before your surgery. your surgery. Coming for surgery: Coming for surgery: Come to the Birthing Unit, 4th fl oor Come to the Birthing Unit, 8th fl oor (See map on page 10) (See map on page 11). -

Ottawa Hospital Case Study

Nuance Healthcare Solutions Case Study Dragon® Medical Network Edition The Ottawa Hospital improves patient care and lowers transcription costs Challenge Solution Results – Improve continuity of care – Dragon Medical Network – Templates improve – Enhance patient safety and Edition complements the documentation accuracy, quality of care Oasis EHR thoroughness and consistency – Reduce transcription costs – Documentation is available two weeks faster – Documentation is accessible throughout the circle of care – Transcription savings of $7 million – $11 million projected savings over 5 years – 37,000 documents created per month vs 3,000 previously Summary The Ottawa Hospital is a 1,149-bed non-profit, academic health sciences center in Ottawa, Canada. It serves 1.3 million people across Eastern Ontario. The Ottawa Hospital was looking to improve patient safety and quality of care by giving all providers within the hospital and throughout the community immediate access to patient records. At the same time, it wanted to be a responsible steward of its financial resources. Nuance Healthcare Solutions Case Study Dragon® Medical Network Edition “ We expect to save $11 million over 5 years because of Dragon Medical. The accessibility of patient records—possible because our clinicians are documenting care electronically—is truly exciting.” Dr. Glen Geiger, CMIO The Ottawa Hospital Ottawa, Canada The first hospital in Canada to implement Dragon® Improved continuity of care Medical Network Edition alongside its Oasis EHR When physicians used phone dictation, the average solution, The Ottawa Hospital has succeeded in ensuring turnaround time for notes was 14 days. Now physicians timely access to accurate and comprehensive patient enter them immediately into the EHR. -

Referral Form to Colorectal Cancer Screening Program

Referral Form to Colorectal Cancer Screening Program FOR HIGH RISK PATIENTS ONLY A guide for referring physicians The Colorectal Cancer Screening Program (CCSP) aims to save lives by improving access to colorectal cancer screening exams for those at increased risk. As the referring physician, you may use the attached form to refer patients to the CCSP at The Ottawa Hospital, Queensway Carleton Hospital or the Montfort Hospital. Once the referral is received at the hospital, patients will be scheduled to have a colonoscopy performed by one of the program physicians. The hospital will communicate directly with the referred patients to educate them about the procedure and the scheduled procedure date. REFERRAL FORM INSTRUCTIONS: Indication for the referral The Colorectal Cancer Screening Program is only applicable to patients who require colonoscopy screening due to a positive Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT), or a colorectal cancer diagnosis in at least one first degree relative (parent, sibling, child). Those being referred to the program with a family history of colorectal cancer should be at least 50 years of age OR ten years younger than the age at which their first degree relative was diagnosed - whichever is younger. All other referrals for colonoscopy must be referred directly to the gastroenterologist or surgeon of your choosing. Note: NO direct referral to any one of the program gastroenterologists or surgeons will be permitted using this program referral form. Significant medical history It is important that all significant and relevant patient medical history be provided on the referral form. If the answer is “Yes” to any of the pre-existing conditions, the patient will be assessed for medical readiness by the physician performing the colonoscopy prior to their scheduled procedure date. -

Contact Information

CONTACT INFORMATION Director of Faculty Wellness University of Ottawa Dr. Caroline Gérin-Lajoie 613-562-5800 x8507 [email protected] Wellbeing Program for Physicians-in-Training TOH Monique Beaulne, Director 613-737-8473 [email protected] PARO Toll Free Help Line 1-866-435-7362 (1-866-HELP-DOC) OMA Physician Health Program 1-800-268-7215 x2972 https://www.oma.org/benefits/pages/PhysicianHealthProgram.aspx Hospital Medical Education Offices Ottawa Hospital: Monique Beaulne, Manager 613-737-8473 [email protected] Ottawa Hospital: Ginette Martell de Martineau, Adm Asst. 613-737-8455 [email protected] Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario: Dana Ducette 613-737-2285 [email protected] Royal Ottawa Hospital: Carmen Lefebvre 613-722-6521 x6811 [email protected] Hôpital Montfort: Louise Martin 613-746-4621 x6036 [email protected] Élisabeth-Bruyère Health Centre: Joanne Dusseault 613-562-6335 x1087 [email protected] How to find a Family Physician Monique Beaulne, Director, Hospital Wellness Office (TOH) 613-737-8473 [email protected] The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario 416-967-2603 http://www.cpso.on.ca/ Academy of Medicine Ottawa Code 99 OMA Regional Section 613-733-2604 http://academymedicineottawa.org/ uOttawa Student Health Services 613-564-3950 http://www.uottawa.ca/health/about/ University of Ottawa Services uOttawa Student Services website..................................................................................................................http://www.uottawa.ca/en/students# -

SENIOR LEADERSHIP TEAM Board of Governors

Katherine Cotton Chair, SENIOR LEADERSHIP TEAM Board of Governors Cameron Love Dr. Virginia Roth Department Heads (12) President and CEO Chief of Staff Dr. Kathleen Gartke Senior Medical Officer Dr. Duncan Stewart • Tracy Wrong President and CEO, Honorata Bittner Director, Medical Affairs Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Chief Strategy Officer and Patient Relations EVP, Research, The Ottawa Hospital Nyranne Martin Dr. Jerry Maniate VP, Education Timothy Kluke General Counsel Dianne Scharf President and CEO, Internal Auditor • Axelle Pellerin The Ottawa Hospital Foundation Melanie Gruer Kate Eggins Director, Education Chief Communications Officer Director, Communications • Dr. Vicki LeBlanc Director, uOSSC Michael Kekewich Director, Clinical and Organizational Ethics and MAiD Program Suzanne Madore Dr. Alan Forster Dr. Renée Légaré Shafique Shamji Joanne Read Nathalie Cadieux EVP, Chief Clinical Officer and EVP and Chief Innovation and EVP and Chief Human Resources EVP and Chief Information EVP and Chief Planning and EVP and Chief Financial Officer Chief Nursing Executive Quality Officer Officer Officer Development Officer Ann Mitchell Kevin Peters Samantha Hamilton Reece Bearnes Robert Burry Tracey Dennis Fred Beauchemin Dr. Glen Geiger Karen Stockton Director, Nursing Professional Executive Director, Clinical Director, Quality and Executive Director, Director, Workforce Executive Director, Executive Director, Business Chief Medical Information Executive Director, Planning and Practice Operations Infection Control Ambulatory and Virtual Optimization Supply Chain and Development and Officer Development • Janet Graham Care Chief Procurement OWN/WSIB Dennis Garvin Alexander Kuo Charlotte Castonguay Stephane Laliberté David Boughton Regional Director, Nephrology Officer Executive Director, Clinical Director, Pharmacy • Nathalie Cleroux Acting Director, Safety, • Paul Richards Director, Systems Integration and Director, Medicine Director, Capital Projects and Director, Julie Clairmont . -

Contents & Introduction

University of Ottawa Campus Master Plan November 2, 2015 University of Ottawa Campus Master Plan 1 Introduction Context Framework and 1 2 3 Big Moves 1.1. Purpose and Goals 2 2.1. Brief History of Campus 12 3.1. Campus Framework 40 Development 1.2. uOttawa’s Campus Locations 4 3.2. Big Moves 52 Campus Precincts 2.2. The Campus in the City 14 Renew the Core Surrounding Neighbourhoods Green the campus 1.3. Study Process 8 Market Overview Transform King Edward Regulatory Context Develop the River Precinct Heritage Start development around Lees Station 2.3. The Campus Today 24 Develop complete communities Facilities Assessment Foster new partnerships 2.4. Projections and Trends 28 Current Projects Accessibility at uOttawa Sustainability at uOttawa 2.5. Directions and Opportunities 36 4 The Plan 5 Precinct Strategies 6 Implementation 4.1. Sites for Renewal 70 5.1. Tabaret 136 6.1. University Projects 164 or Redevelopment 5.2. Core 140 6.2. Tools and Strategies 166 4.2. Land Use 72 5.3. King Edward 144 4.3. Community Hubs 76 5.4. Mann 148 4.4. Research Facilities Strategy 81 5.5. River, Robinson and Station 152 4.5. Housing Strategy 82 5.6. Peter Morand and 156 4.6. Open Space and Streetscapes 90 Roger Guindon 4.7. Campus Identity 102 4.8. Mobility 106 4.9. Alta Vista 119 4.10. Servicing and Utilities 124 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION vi UOTTAWA CAMPUS MASTER PLAN The University of Ottawa holds a prominent place nationally and internationally as one of Canada’s leading universities and the largest bilingual university in the world. -

Innovation and Excellence Never Ends!

HÔPITAL MONTFORT: WHERE THE SEARCH FOR INNOVATION AND EXCELLENCE NEVER ENDS! annualreport 2012|2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS P.4 Watch our videos! • Message from the Chair of the Board, the CEO and the Medical Chief of Staff of Hôpital Montfort • Testimonials and interviews P.6 Members of the Board of Trustees P.7 Chiefs — Medical Department P.7 Physician Executive Council P.8 Committees and Presidents P.26 Auxiliaries/Volunteers Association P.28 Montfort Hospital Foundation P.30 Financial statements P.10 | PROVIDING THE FIVE MAIN DIRECTIONS QUALITY CARE GUIDED WHAT’S NEW THIS YEAR? BY BEST PRACTICES1 P.17 | PROVIDING STAFF P.14 | NEW METHODS MEMBERS WITH A HEALTHY FOR IMPROVING THE WORK ENVIRONMENT WHERE HOSPITAL’S EFFECTIVENESS THEY CAN ACHIEVE THEIR 2 FULL POTENTIAL 3 P.19 | CLOSE COLLABORATION P.22 | EMPHASIS ON RESEARCH WITH PARTNERS AND THE AND ENSURING A SUCCESSION COMMUNITY FOR THE THAT CAN MEET THE NEEDS WELL-BEING OF PATIENTS OF TOMORROW’S COMMUNITY 4 5 ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2013 3 Life strength or « Force de vivre »: discover the story of WATCH the Smith-Johnston’s family. OUR VIDEOS! Learn how research conducted by researchers at the Institut de recherche de l’Hôpital Montfort Message from the Chair of the Board, the CEO and the Medical Chief of Staff (IRHM) improves healthcare for of Hôpital Montfort Francophones. An unforgettable encounter: the testimony of Councillor Stephen Blais. French training of future health professionals in Ontario: a priority for Hôpital Montfort. 4 HÔPITAL MONTFORT ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2013 5 MEMBERS OF THE CHIEFS — MEDICAL DEPARTMENT BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dr. -

Completing the New Outpatient MRI Referral Documentation

Tip Sheet: Completing the New Outpatient MRI Referral Documentation The MRI service providers in the Ottawa Valley and Eastern Ontario have centralized the intake for outpatient MRI scan requests. As of December 9, 2019, all outpatient MRI referrals must be submitted through the Central Intake Program using the new regional requisition form. The form is available in English and French from the Central Intake Program website: www.ottawahospital.on.ca/en/mricentralintake. This document includes important information regarding how to complete certain sections of the new requisition form including how to indicate certain information related to your patient’s unique needs and choices. Items with an asterisk (*) on the new form are mandatory fields. Completing the Patient Information Section: Please fill out the patient information completely. Preferred language: Indicating a preferred language in this section will allow the receiving site to arrange for resources to accommodate the patient in their preferred language. For patients who wish to receive services in French: Hôpital Montfort is Ontario’s Francophone academic hospital and the only hospital in the region guaranteeing services in French throughout the hospital. Cornwall Community Hospital and The Ottawa Hospital’s General Campus are also designated under the French Language Services Act for most services in diagnostic imaging. Please see instructions below regarding how to select a specific site. Patient e-mail: Some MRI sites use e-mail notifications to patients to notify them of appointment updates and reminders. If your patient consents to receive e-mail communication, please indicate that consent on the form. Consenting to e-mail communication does not guarantee communication by e- mail. -

Geriatric Day Hospital, the Ottawa Hospital, Civic Campus

Geriatric Day Hospital The First Visit Return visits The Ottawa Hospital Civic Campus The patient’s first visit is often 3-4 The patient can expect to have four hours in length as it includes a to five visits scheduled over several eriatric thorough medical and nursing weeks. These visits can last one to G Our Purpose assessment. The appointment three hours. begins at 9:00 am. Day Hospital To provide comprehensive Many visits are required as patients multidisciplinary assessment for The patient must bring all can fluctuate day to day. This also The Ottawa patients who are experiencing a medications to the first visit. helps to reduce fatigue in each change in function, memory, mood, session. Hospital, Civic or have complex medical issues. An involved family member, Short-term treatment, counseling, caregiver, or friend must Patients will not see the Geriatrician Campus and education are available to accompany the patient to the first on each visit. The Geriatrician will patients and their caregivers to visit. communicate with the referring facilitate community support and family physician as needed. long-term care planning. This is important to provide their perspective and to help establish If there are any medical Referral Process goals for the assessment. emergencies during the assessment period, please contact Patients are usually referred by Our Team your own family physician. their family or physicians. At times, patients will be referred through the The Ward Clerk will act as the Completion of Day Hospital Emergency Department (Geriatric initial contact. The Ward Clerk Assessment: Emergency Management Program). will provide the first appointment date. -

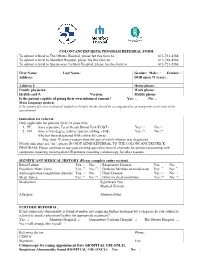

Coloncancercheck Program Referral Form

COLONCANCERCHECK PROGRAM REFERRAL FORM To submit referral to The Ottawa Hospital, please fax this form to: 613-761-4388 To submit referral to Montfort Hospital, please fax this form to: 613-748-4968 To submit referral to Queensway Carleton Hospital, please fax this form to: 613-721-5368 First Name: Last Name: Gender: Male: Female: Address: DOB (max 74 years): Address 2: Home phone: Family physician: Work phone: Health card #: Version: Mobile phone: Is the patient capable of giving their own informed consent? Yes: No: Main language spoken: If the patient does not read/speak English or French, he/she should be accompanied by an interpreter at the time of the appointment. Indication for referral: Only applicable for patients 50 to 74 years who 1. PF: have a positive Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) Yes: No: 2. FD: have a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, child) Yes: No: who has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer. May start 10 years younger than the age at which relative was diagnosed. If both indicators are “no”, please DO NOT SEND REFERRAL TO THE COLONCANCERCHECK PROGRAM. Please continue to use your existing specialist referral channels for patients presenting with symptoms requiring investigation OR patients requiring colonoscopy for other reasons. SIGNIFICANT MEDICAL HISTORY (Please complete entire section) Renal Failure Yes: No: Respiratory Disease Yes: No: Prosthetic Heart Valve Yes: No: Diabetes Mellitus on medication Yes: No: Anticoagulation/coagulation disorder Yes: No: Heart Disease Yes: