Oral History Interview with Marilyn Minter, 2011 Nov 29-30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written and Illustrated by Melanie Wallace Dedicated to My Family: Dad, Mom, Chris, Cathy, Bill & Ben Love You Guys

written and illustrated by Melanie Wallace dedicated to my family: Dad, Mom, Chris, Cathy, Bill & Ben love you guys I am standing at the gate by the creek. The Today, I am going through creek runs under the road that is behind the gate. me, through a large metal culvert filled with spider webs and dumps into a large pool of water which I think is very deep. Before I get to the gate, I step off the road and down a steep ditch. I have to go slow, because there is barbed wire all over. There is a stone wall too. Some times I sit on the stone wall, throwing things in the creek and watching them float down stream. Sometimes I drop things on the other side of the road and run across, waiting for them to float through. The gate has metal bars in the shape of an X with the barbed wire woven through. We’ve stepped on the wire enough to make a small hole to crawl through. I am sitting in my Dad’s hospice room. In has a happy face. Ben is nine years younger. front of me, lies my father in a bed. His arms He looks and acts a lot like me with brown and legs are very thin and he sleeps most of hair, blue eyes and the same ambition to be the time. To the right is his bathroom with a productive everyday, like our Dad. large walk-in shower. To the left are beautiful views of the trees and snow through large It’s just coincidence that we are together patio doors. -

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

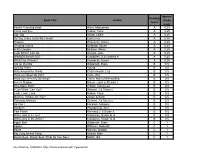

Vendors by Managing Organization

Look up by Vendor, then look at managing dispatch. This dispatch center holds the virtual ownership of that vendor. When the vendor obtains their NAP user account, the vendor would then call this dispatch center for Web statusing permissions. You can run this list in ROSS reports: use the search function, type "vendors" or "managing" then search. Should show up. You can filter and sort as necessary. Managing Org Name Org Name Northwest Coordination Center 1-A Construction & Fire LLP Sacramento Headquarters Command Center 10 Tanker Air Carrier LLC Northwest Coordination Center 1A H&K Inc. Oregon Dept. of Forestry Coordination Center 1st Choice Contracting, Inc Missoula Interagency Dispatch Center 3 - Mor Enterprises, Inc. Southwest Area Coordination Center 310 Dust Control, LLC Oregon Dept. of Forestry Coordination Center 3b's Forestry, Incorporated State of Alaska Logistics Center 40-Mile Air, LTD Northern California Coordination Center 49 Creek Ranch LLC Northern California Coordination Center 49er Pressure Wash & Water Service, Inc. Helena Interagency Dispatch Center 4x4 Logging Teton Interagency Dispatch Center 5-D Trucking, LLC Northern California Coordination Center 6 Rivers Construction Inc Southwest Area Coordination Center 7W Enterprises LLC Northern California Coordination Center A & A Portables, Inc Northern California Coordination Center A & B Saw & Lawnmowers Shop Northern Rockies Coordination Center A & C Construction Northern California Coordination Center A & F Enterprises Eastern Idaho Interagency Fire Center A & F Excavation Southwest Area Forestry Dispatch A & G Acres Plus Northern California Coordination Center A & G Pumping, Inc. Northern California Coordination Center A & H Rents Inc Central Nevada Interagency Dispatch Center A & N Enterprises Northern California Coordination Center A & P Helicopters, Inc. -

1961 Climbers Outing in the Icefield Range of the St

the Mountaineer 1962 Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office in Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and December by THE MOUNTAINEERS, P. 0. Box 122, Seattle 11, Wash. Clubroom is at 523 Pike Street in Seattle. Subscription price is $3.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of Northwest America; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfillment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor Zif e. EDITORIAL STAFF Nancy Miller, Editor, Marjorie Wilson, Betty Manning, Winifred Coleman The Mountaineers OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES Robert N. Latz, President Peggy Lawton, Secretary Arthur Bratsberg, Vice-President Edward H. Murray, Treasurer A. L. Crittenden Frank Fickeisen Peggy Lawton John Klos William Marzolf Nancy Miller Morris Moen Roy A. Snider Ira Spring Leon Uziel E. A. Robinson (Ex-Officio) James Geniesse (Everett) J. D. Cockrell (Tacoma) James Pennington (Jr. Representative) OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES : TACOMA BRANCH Nels Bjarke, Chairman Wilma Shannon, Treasurer Harry Connor, Vice Chairman Miles Johnson John Freeman (Ex-Officio) (Jr. Representative) Jack Gallagher James Henriot Edith Goodman George Munday Helen Sohlberg, Secretary OFFICERS: EVERETT BRANCH Jim Geniesse, Chairman Dorothy Philipp, Secretary Ralph Mackey, Treasurer COPYRIGHT 1962 BY THE MOUNTAINEERS The Mountaineer Climbing Code· A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. -

Stress Reduction Technique: Guided Imagery – Meadow and Stream

Leader Version The START Manual: STrAtegies for RelaTives Adapted from the original Coping with Caregiving with thanks to Dolores Gallagher-Thompson, Stanford University School of Medicine, for her kind permission. Produced by MHSU UCL Page 1 Contents Session 1: Stress and Well-Being 5 Session 2: Reasons for Behaviour 23 Session 3: Making a Behaviour Plan 45 Session 4: Behaviour Strategies and Unhelpful Thoughts 63 Session 5: Communication Styles 85 Session 6: Planning for the Future 105 Session 7: Introduction to Pleasant Events and your Mood 133 Session 8: Using your skills in the future 153 Page 2 Introduction These sessions are about you, and how to maintain or improve your well-being when caring is stressful. Some people find it helpful to think of themselves as a carer, others describe themselves as just acting the way a relative does. How would you describe yourself? Leader: Remember this and use their preferred description throughout if different to carer, the term used in this manual. Caring is challenging, and many skills are needed. The sessions will focus on your thoughts, feelings, and reactions to looking after someone with memory loss. We will look at: Strategies to manage the difficult behaviours which are often associated with memory problems, so they are less upsetting. Strategies focusing on your sense of well-being, including ways to relax. Although we can’t guarantee that all difficult behaviours will change, we hope to provide you with some tools to improve your situation. During my visits we will cover some strategies which help many people. You may be doing some already and not all will apply to you. -

Scénario Pédagogique

Isabelle_cahier_fr01.qxp:Layout 1 11/5/07 10:48 PM Page 1 SCÉNARIO PÉDAGOGIQUE UNE PRODUCTION DE L’OFFICE NATIONAL DU FILM DU CANADA Isabelle_cahier_fr01.qxp:Layout 1 11/5/07 10:48 PM Page 2 Scénario pédagogique préparé par Louise Sarrasin, enseignante Commission scolaire de Montréal (CSDM), Montréal, Québec Scénario, animation, réalisation : Claude Cloutier Production : Marcel Jean Une production et une distribution de l’Office national du film du Canada 2007 – 9 min 14 s Technique : dessin sur papier RENSEIGNEMENTS : 1-800-267-7710 Site Internet : <www.onf.ca> Isabelle_cahier_fr01.qxp:Layout 1 11/5/07 10:48 PM Page 3 SCÉNARIO PÉDAGOGIQUE OBJECTIF GÉNÉRAL Donner l’occasion à l’élève d’apprécier des œuvres littéraires à partir du film d’animation Isabelle au bois dormant. PUBLIC CIBLE Élèves de 10 à 14 ans DOMAINES D’APPRENTISSAGE Langues et littérature – Arts et culture – Sciences sociales SOMMAIRE Ce scénario pédagogique permettra aux élèves d’explorer l’univers des contes. Il leur fera réaliser que le film d’animation se prête bien à ce genre littéraire. AMORCE ET ACTIVITÉ PRÉPARATOIRE : Des contes pour tous les goûts! Durée approximative : 60 minutes Pour débuter, mettez à la disposition des élèves des contes de Perrault et des frères Grimm (dont La belle au bois dormant) . Laissez vos élèves découvrir ces œuvres avant d’entamer une discussion à l’aide de ces questions : •Quel conte vous plaît le plus? Quel est votre personnage préféré? Expliquez. •Que connaissez-vous du conte La Belle au bois dormant ? •Qu’êtes-vous en mesure de dire de l’époque des châteaux? Une fois la discussion terminée, demandez à vos élèves d’illustrer un aspect de leur œuvre préférée. -

DEGLI ANGELI, LA LAVERTY Paul 2012 UK/France/Belgium/Ital 2

N. Titolo Regia Anno Nazione 1 "PARTE" DEGLI ANGELI, LA LAVERTY Paul 2012 UK/France/Belgium/Ital "SE TORNO" - ERNEST PIGNON- 2 COLLETTIVO SIKOZEL 2016 Italy/France ERNEST E LA FIGURA DI PASOLINI 3 ... E FUORI NEVICA SALEMME Vincenzo 2014 Italy 4 ... E FUORI NEVICA SALEMME Vincenzo 2014 Italy 5 ...E L'UOMO CREO' SATANA KRAMER, Stanley 1960 USA 6 ...E ORA PARLIAMO DI KEVIN RAMSAY, Lynne 2011 GB ¡VIVAN LAS ANTIPODAS! - VIVE LES Germany/Argentina/Net 7 KOSSAKOVSKY Victor 2011 ANTIPODES! (VIVA GLI ANTIPODI!) herlands/Chile ¡VIVAN LAS ANTIPODAS! - VIVE LES Germany/Argentina/Net 8 KOSSAKOVSKY Victor 2011 ANTIPODES! (VIVA GLI ANTIPODI!) herlands/Chile 007 - CASINO ROYALE - QUANTUM CAMPBELL, Martin - FORSTER, Marc - 9 2006-2012 USA / GB / Italy OF SOLACE - SKYFALL MENDES, Sam 10 007 - DALLA RUSSIA CON AMORE YOUNG, Terence 1963 USA 11 007 - GOLDENEYE CAMPBELL Martin 1995 UK/USA 12 007 - IL DOMANI NON MUORE MAI SPOTTISWOODE Roger 1997 UK/USA 13 007 - IL MONDO NON BASTA APTED, Michael 1999 USA 14 007 - IL MONDO NON BASTA APTED Michael 1999 UK/USA 15 007 - LA MORTE PUO' ATTENDERE TAMAHORI, Lee 2002 USA 16 007 - LICENZA DI UCCIDERE YOUNG, Terence 1962 USA 17 007 - MAI DIRE MAI KERSHNER, Irvin 1983 GB / USA / Germany 18 007 - MAI DIRE MAI KERSHNER Irvin 1983 UK/USA/West Germany 19 007 - MISSIONE GOLDFINGER HAMILTON, Guy 1964 USA 007 - MOONRAKER - OPERAZIONE 20 GILBERT, Lewis 1979 USA SPAZIO 21 007 - QUANTUM OF SOLACE FORSTER, Marc 2008 USA 22 007 - SOLO PER I TUOI OCCHI GLEN, John 1981 USA 007 - THUNDERBALL - OPERAZIONE 23 YOUNG, Terence 1965 USA TUONO -

Marilyn Minter Biography

MARILYN MINTER BIOGRAPHY Born in Shreveport, Louisiana, 1948. Lives and works in New York, NY. Education: M.F.A., Syracuse University, 1972 B.F.A., University of Florida, 1970 Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2021 “Marilyn Minter: All Wet,” Montpellier Contemporain — Panacée, Montpellier, France, June 26 – September 5, 2021; catalogue “Marily Minter: Smash,” MoCA Westport, Westport, CT, April 2 – June 13, 2021 2020 “Marilyn Minter: Nasty Woman,” SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA, February 11 – August 2, 2020 “Marilyn Minter: Splash!,” School of Visual Arts Armory Gallery, Blacksburg, VA, January 29 – February 22, 2020 2019 “Marilyn Minter,” Simon Lee Gallery, London, UK, June 6 – July 13, 2019 2018 “Marilyn Minter,” Lehmann Maupin, Hong Kong, China, August 30 – October 27, 2018 “Marilyn Minter: Smash + New Photographs,” Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, July 27 – September 4, 2018 “Channel 3: Marilyn Minter,” Ratio 3, San Francisco, CA, June 2 – July 7, 2018 “Marilyn Minter,” Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA, May 19 – June 23, 2018 2016 “Marilyn Minter: Spray On,” Carolina Nitsch, New York, NY, November 18, 2016 – January 20, 2017 “Marilyn Minter,” Salon 94 Bowery, New York, NY, October 27 – December 22, 2016 2015 “Marilyn Minter: New Paintings and Photographs,” Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, November 27 – December 21, 2015 “Marilyn Minter,” Salon 94, New York, NY, October 27 – December 22, 2016 “Marilyn Minter: I'm Not Much But I'm All That I Think About,” Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, October 2, -

Marilyn Minter's Politically Incorrect Pleasures

MARILYN MINTER’S POLITICALLY INCORRECT PLEASURES ELISSA AUTHER of Lena Dunham and Beyoncé, gaze as much as they invite it. Furthermore, her interest in IN THE AGE it is hard to imagine that only two physical flaws and soiled elegance undermines the illusions of or three decades ago, progressive- minded people derided the perfection normally promoted by the glossy commercial image. free display of female sexuality.1 But that is exactly the unfriendly Minter often reveals much more than we want to see. It is in the context in which Marilyn Minter first offered up her body of collision of these two powerful aesthetic forces, the beautiful technically virtuosic and openly erotic paintings. Minter’s and the grotesque—what Minter has described as the “path- career- long exploration of beauty, desire, and pleasure- in- ology of glamour”5—that the artist presents her compelling looking has occupied, at best, an uneasy place within feminist visual investigation into the nature of our passions and fantasies, art history and criticism. Her painted and photographic appro- finding them unruly and highly resistant to ideological correction. priations of pornographic imagery, physical flaws, and high From Minter’s earliest forays as an artist, the female body fashion never function as easy, straightforward critiques of has been the primary vehicle through which she has addressed patriarchal culture. As one critic has remarked, “It is difficult to issues of beauty and desire. Her series of black- and- white tell if Marilyn Minter’s subjects are meant to make viewers photographs of her mother (cats. 1–5), shot in 1969, when uncomfortable—or turn them on.”2 That Minter’s work insists she was still an undergraduate at the University of Florida, on both has always been a challenge for viewers who require Gainesville, went straight to the heart of the conventions and confirmation that she is on the correct side of the political artifice of feminine beauty. -

Samplembe Reprint2010.Qxp 1/29/2010 10:00 AM Page 1

SampleMBE_reprint2010.qxp 1/29/2010 10:00 AM Page 1 Sample MBE February 1991 ® PREFACE The Multistate Bar Examination (MBE) is an objective six-hour examination developed by the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) that contains 200 questions. It was first administered in February 1972, and is currently a component of the bar examination in most U.S. jurisdictions. From time to time NCBE releases test questions to acquaint test- takers with authentic test materials. This publication consists of the actual 200-item, multiple-choice test that was administered nationally in February 1991. Fifty of these items were initially published in the 1992 MBE Information Booklet and were included in MBE Questions 1992. The February 1991 MBE consisted of questions in the following areas: Constitutional Law, Contracts, Criminal Law and Procedure, Evidence, Real Property, and Torts. Applicants were directed to choose the best answer from four stated alternatives. The purpose of this publication is to familiarize you with the format and nature of MBE questions. The questions in this publication should not be used for substantive preparation for the MBE. Because of changes in the law since the time the examination was administered, the questions and their keys may no longer be current. The editorial style of questions may have changed over time as well. Applicants are encouraged to use as additional study aids the MBE Online Practice Exams 1 and 2 (MBE OPE 1 and OPE 2), both available for purchase online at www.ncbex2.org/catalog. These study aids, which include explanations for each option selected, contain questions from more recently administered MBEs that more accurately represent the current content and format of the MBE. -

MARILYN MINTER 1948 Born: in Shreveport, LA 1970 B.F.A

MARILYN MINTER 1948 Born: in Shreveport, LA 1970 B.F.A., University of Florida, Gainesvile, FL 1972 M.F.A. Painting, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 2007 Used Pamela Anderson as a muse for the Parkett centerfold Lives and works in New York, NY Selected Exhibitions 2009 - 2010 Chewing Color, Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH (solo) 2009 200 Artworks – 25 Years” Artists’ Editions for Parkett, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan 2009 Objects of Value, Miami Art Museum, Miami, FL 2009 The Glamour Project, Lehmann Maupin gallery, New York, NY 2009 The Palace at 4 a.m., Gana Art Gallery, New York, NY 2009 For Your Eyes Only, De Markten, Brussels, Belgium 2009 We’re all gonna die., Sue Scott Gallery, New York, NY, June 25 – July 31 2009 Pretty Is And Pretty Does, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, NM (Feb – May) 2009 Regen Projects II, Los Angeles (solo) S A R A H B E L D E N F I N E A R T SAN JUAN DE LA CUESTA 1 4A 28017 MADRID, SPAIN TEL +34 633 170 463 / [email protected] 2009 Salon 94 Freemans, New York (solo) 2008 Andrehn-Schiptjenko Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden (solo) 2008 Darkside, Fotomuseum, Winterthur, Switzerland 2008 Agency: Art and Advertising, McDonough Museum of Art, Youngstown State University, Youngstown, OH 2008 Expenditure, Busan Biennale, Busan, Korea 2008 Whatever’s Whatever Hydra School Projects, Hydra, Greece 2008 Sweat, Marilyn Minter + Mika Rottenberg, Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris, France 2007 Rock’n’ Roll Vol. I, Norrköpings Konstmuseum, Norrköping, Sweden, Sørlandets Konstmuseum, Kristiansand, -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx.