The Making of the Greatest Team in the World GRAHAM HUNTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Iv Individual Player Contributions in European Soccer

Guy Wilkinson PhD Thesis (2017) CHAPTER IV INDIVIDUAL PLAYER CONTRIBUTIONS IN EUROPEAN SOCCER ABSTRACT This paper looks at applying new techniques to predict match outcomes in professional soccer. To achieve this models are used which measure the individual contributions of soccer players within their team. Using data from the top 25 European soccer leagues, the individual contribution of players is measured using high dimensional fixed effects models. Nine years of results are used to produce player, team and manager estimates. A further year of results is used to check for predictive accuracy. Since this has useful applications in player scouting the paper will also look at how well the models rank players. The findings show an average prediction rate of 45% with all methods showing similar rankings for player productivity. While the model highlights the most productive players there is a bias towards players who produce and prevent goals directly. This results in more attackers and defenders ranking highly than midfield players. There is potential for these techniques to be used against the betting market as most models produce better performance than many betting firms. Guy Wilkinson PhD Thesis (2017) 1. INTRODUCTION This paper focuses on producing models with a high prediction rate in professional soccer. The main challenge is to produce accurate estimations of player ability, a problem analogous to research on worker productivity. The study of worker productivity is of great value to businesses in almost every industry. Hiring the best workers will improve the overall performance of business and increase profit. It is of great importance for firms to be able to screen potential employees efficiently to determine their value. -

Zaragoza: Light Rail Perfected?

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com JANUARY 2018 NO. 961 ZARAGOZA: LIGHT RAIL PERFECTED? Cambridge: Tramway plans for a historic UK city Thai cities to create four lines in 2018 VDV to lead new tram-train alliance Dublin opens Luas Cross City line F rench lessons Houston 01> £4.60 Successful urban US city debates the tram integration future role of transit 9 771460 832067 “I very much enjoyed “The presentations, increased informal Manchester networking, logistics networking opportunities and atmosphere were in such a superb venue. excellent. There was a The 12th Annual Light Rail common agreement Conference quite clearly 17-18 July 2018 among the participants marked a coming of age that the UK Light Rail as the leader on light rail Conference is one of worldwide, as evidenced the best in the industry.” by the depth of analysis The UK Light Rail Conference and exhibition is the simcha Ohrenstein – from quality speakers and ctO, Jerusalem Lrt the active participation of premier knowledge-exchange event in the industry. transit Masterplan key industry players and suppliers in the discussions.” With unrivalled networking opportunities, and a Ian Brown cBe – Director, UKtram 75% return rate for exhibitors, it is well-known as the place to do business and build valuable and “This event gets better every year; the 2018 long-lasting relationships. dates are in the diary.” Peter Daly – sales & There is no better place to gain true insight into services Manager, thermit Welding (GB) Voices the workings of the sector and help shape its future. V from the t o discuss how you can be part of it, industry… visit us online at www.mainspring.co.uk “An excellent conference as always. -

Real Madrid Gana Al Barza; 1-2 De Crear Huecos En La Defensa Andaluza

10238857 12/07/2003 05:11 p.m. Page 2 2D |EL SIGLO DE DURANGO | DOMINGO 7 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2003 | DEPORTES LOGRO | EL CUADRO DE “EL VASCO” SE IMPUSO 3-2 PARA ENCADENAR DOS TRIUNFOS CONTINUOS Triunfa el Osasuna El técnico del Celta, Mi- guel Ángel Lotina, que regresaba a El Sadar, sabía lo difícil del cotejo PAMPLONA, ESPAÑA (EFE).- Osasuna encadenó dos victorias por prime- ra vez en la temporada y de paso rompió el gafe que le perseguía an- te el Celta en El Sadar, donde los gallegos había ganado en sus tres últimas visitas sin encajar un solo gol, en un partido desequilibrado por el delantero australiano John Aloisi, autor de los dos primeros goles ‘rojillos’ y de la asistencia del tercero de Bakayoko (3-2). Semana redonda para el con- junto de Javier Aguirre, ya que Buenas jugadas en el Riazor. (Reuters) sumó siete puntos, con triunfos frente al Español y Celta y empa- te ante el Real Madrid. La de ayer La Coruña derrota fue una victoria trabajada ante un equipo en horas bajas, que aprove- chó dos errores del portero local al Málaga en Riazor Sanzol para meterse en el partido. El técnico del Celta, Miguel Ángel Lotina, que regresaba a El Sadar, lo había anunciado antes LA CORUÑA, ESPAÑA (EFE).- El Deportivo de La Co- del partido: “Osasuna es el equi- ruña venció por la mínima diferencia a un Málaga po que mejor juega en la actuali- que puso en muchos problemas a los locales, con dad de España”. El equipo nava- un tanto de Joan Capdevila, que acabó con la ma- rro no desplegó el futbol de otros ña racha que sufría su equipo, que llevaba seis jor- partidos, pero sacó los tres pun- nadas sin anotar en el arco rival (exceptuando los tos con oficio y con una actuación tres goles en contra con los que se vio beneficiado). -

Aragonés Qüiere Mostrar El Mejor Süker a Floro

pero no hay que verter más tinta sobre eso. Encontrará la for ma y todo cambiará cuando meta un gol. He hablado con él del asunto y ahora está anímicamente bien, después de su Aragonés qüiere mostrarperar algunos problemas por las convocatoriascon su selec - . ción, pero esta semana se ha entrenado con ganas”. El brasi leño Moacir debutará en Liga ante su público, pues en los • otros dos partidos que jugó el Sevilla en casa él estaba lesio - el mejor Süker a Floro nado y no pudo actuar. El técnico madrileño, sobre el Albacete, manifestó que el equipo de Benito Floro “será complicado, pues usa un siste El Albacete, a romper su historia de fracasos ante el Sevillama;1] táctico defensivo. El Albacete no comenzó bien la com petición, pero cada partido es distinto y ahora el equipo ha Sánchez Pizjuán h.17.00;0] JESÚS GÓMEZ/PEDRO LÍBERO . SEVILLA/ALBACETE cambiado de entrenador y de sistema. De todas maneras, mi 1 Sevilla recibe esta tarde al Albacete en un partido preocupación es el juego del Sevilla y no el del Albacete, aun SEVILLA FC ALBACETE que siempre hay que tenerle todo el respeto”. Unzué. Prieto, Diego, Martagón. Marcos. Coco, Santi, Fradera, que está marcado por la personalidad de los técni Rafa Paz. Marcos, Moacir, Moya. Oliete, Oscar, Zalazar, Sala, cos de ambos equipos. Luis Aragonés, en el de los Benito Floro, por su parte, recordó que “el Albacete Soler. Tevenet y Suker. Sotero. Dertycia y Andonov. nunca ha podido vencer al Sevilla, ni en Liga ni en amistosos. Suplentes: Balaguer (p.s.). -

Apba Pro Soccer Roster Sheet

APBA PRO SOCCER ROSTER SHEET - 2011-12 Spanish League Real Madrid Barcelona Valencia Malaga Champions 2nd Place 3rd Place 4th Place Wins 32 Wins 28 Wins 9 Wins 17 Draws 4 Draws 7 Draws 14 Draws 7 Losses 2 Losses 3 Losses 15 Losses 14 Home Away Home Away Home Away Home Away Team Rating 5 5 Team Rating 5 4 Team Rating 3 2 Team Rating 4 2 Team Defense 3 4 Team Defense 4 4 Team Defense 3 2 Team Defense 3 2 Clutch Points 10 10 Clutch Points 10 8 Clutch Points 6 3 Clutch Points 8 3 "JESE" 4 FONTÁS 8 IBAÑEZ 5 CAMACHO 7 CARVALHO 8 BARTRA 7 "BRUNO" 7 GÁMEZ 7 ARBELOA 7 MUNIESA 7 RUIZ 8 MATHIJSEN 8 ALBIOL 8 MASCHERANO 8 "MIGUEL" 6 SÁNCHEZ 7 ALTINTOP 5 BUSQUETS 8 ALBELDA 7 MONREAL 7 DIARRA 6 ABIDAL 7 ALCACER 3 TOULALAN 8 "PEPE" 8 AFELLAY 4 TOPAL 7 "RECIO" 7 COENTRAO 6 "MAXWELL" 6 BARRAGAN 6 PORTILLO 5 ALONSO 7 MONTOYA 6 MADURO 7 DEMICHELIS 8 RAMOS 8 dos SANTOS 6 BERNAT 6 "WELIGTON" 8 GRANERO 6 PUYOL 9 ALBA 6 "APOÑO" 6 SAHIN 7 KEITA 7 RAMI 8 MARESCA 6 ÖZIL 4 PIQUÉ 8 MATHIEU 7 "DUDA" 6 VARANE 8 "ADRIANO" 6 PAREJO 6 FERNÁNDEZ 4 "MARCELO" 6 CUENCA 3 PIATTI 4 "JUANMI" 3 KHEDIRA 6 "THIAGO" 5 COSTA, R. 7 BUONANOTTE 4 MORATA 3 ROBERTO 5 FEGHOULI 4 "JOAQUIN" 4 CALLEJÓN 5 ALVES 6 MADRAZO 4 "ELISEU" 5 "KAKA" 4 "XAVI" 6 "PABLO" 4 van NISTELROOY 3 HIGUAÍN 4 TELLO 4 COSTA, A. -

Bol Pre Mňa Vyslobodením,“

NAJLEPŠIE KURZY – SUPERŠANCA 1 X 2 12763 JIHLAVA – KADAŇ 1,60 4,70 5,20 17:30 12805 VITEBSK – NOVOPOLOCK 4,95 4,90 1,60 17:30 13032 PETROHRAD – MONACO 1,77 3,70 6,00 18:00 12803 LINKÖPING – LEKSAND 1,60 4,70 5,20 19:00 12792 MEDVEŠČAK ZÁHREB – PETROHRAD 6,20 5,30 1,47 20:00 12811 LUDOGOREC – REAL MADRID 18,7 7,50 1,20 20:45 13033 LEVERKUSEN – BENFICA 1,95 3,60 4,60 20:45 13034 ARSENAL – GALATASARAY 1,62 4,10 7,20 20:45 Streda • 1. 10. 2014 • 68. ročník • číslo 225 • cena 0,55 13035 ANDERLECHT – DORTMUND 5,90 4,10 1,70 20:45 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android Kompletnú ponuku nájdete v pobočkách a na www.nike.sk Znovuzrodený! Strana 5 „Odchod z Norimbergu bol pre mòa vyslobodením,“ vraví RÓBERT MAK ešte Kvalifikácia 8dní ME 2016 WWW.SPORT.SK Slovenský futbalový reprezentant Róbert Mak je po letnom prestupe z 1. FC Norimberg do PAOK Solún ako znovuzrodený, v piatich ligo- vých zápasoch strelil štyri góly a momentálne je najlepším kanonierom gréckej ligy. Za jeho ve¾kou pohodou je najmä mladá rodinka, manželka Zuzka, ich syn Robin i štvornohý miláèik... FOTO WWW.PAOKFC.GR To tu ešte nebolo: Helene Vondráčkovej Basketbalisti pozor: Dvanásť kôl bez sa páčil brankár oddnes máte trénerského vyhadzova! Slovana Janus nové pravidlá Strana 4 Strany 14 a 15 Strana 29 2 FUTBAL streda ❘ 1. 10. 2014 8 DNÍ DO ZÁPASU ROKA SLOVENSKO – ŠPANIELSKO Barcelonské maximum prekonal až Guardiola ešte Rodák zo Šiah FERDINAND DAUČÍK sa na trénerskej dráhe zapísal Kvalifikácia do histórie španielskeho klubového futbalu veľkými písmenami 8dní ME 2016 Na jar 1950 zavítalo na Chamartin, domovský štadión Real Madrid, mužstvo s názvom FC Hungaria. -

L'ingratitude Des Dirigeants Du FC Valence

Sport / Actualité foot Feghouli n’a même pas eu droit à un adieu à Mestalla L’ingratitude des dirigeants du FC Valence Pourtant, il était une des coqueluches du Mestalla malgré la présence de joueurs de haut niveau à l’image du légendaire Albelda, Evan Banega, Negredo, Parejo et autre Soldado. Mais ce statut n’a pas plaidé en faveur de l’international algérien, Sofiane Feghouli, poussé vers la sortie comme un malpropre. Les dirigeants du FC Valence ont tout simplement été ingrats envers un joueur qui a été très correct durant les six années passées avec Los Ches. En effet, l’Algérien était arrivé à Valence en 2010 en provenance de Grenoble, et petit à petit, il s’est fait une place dans l’effectif valencien, surtout après son retour de prêt à Almeria en 2011. Feghouli a porté le maillot de Valence à 244 reprises, il y a inscrit pas moins de 42 buts et a délivré 38 passes décisives. Des chiffres et une présence qui méritent une meilleure fin. “J'aime beaucoup Feghouli. C’est un joueur de qualité. Il n'y a pas beaucoup de joueurs comme lui”, avait déclaré, récemment, Roberto Ayala, l’un des joueurs emblématiques du CF Valencia au sujet du joueur algérien dans une interview accordée à un journal espagnol. Outre les Espagnols Fernando Gómez (553), Ricardo Arias (501), David Albelda (410), Santiago Cañizares (397), Pep Claramunt (381), Ruben Baraja (361), Carlos Marchena (317), Gaizka Mendieta (305), Manuel Mestre (323), Antonio Puchades (290), l'Espagnol David Villa (273), le Brésilien Waldo (296), l'Argentin Roberto Ayala (251) et l'Italien Amedeo Carboni (245), Feghouli fait partie des joueurs étrangers ayant joué plus de matches sous les couleurs de Valence. -

Who Can Replace Xavi? a Passing Motif Analysis of Football Players

Who can replace Xavi? A passing motif analysis of football players. Javier Lopez´ Pena˜ ∗ Raul´ Sanchez´ Navarro y Abstract level of passing sequences distributions (cf [6,9,13]), by studying passing networks [3, 4, 8], or from a dy- Traditionally, most of football statistical and media namic perspective studying game flow [2], or pass- coverage has been focused almost exclusively on goals ing flow motifs at the team level [5], where passing and (ocassionally) shots. However, most of the dura- flow motifs (developed following [10]) were satis- tion of a football game is spent away from the boxes, factorily proven by Gyarmati, Kwak and Rodr´ıguez passing the ball around. The way teams pass the to set appart passing style from football teams from ball around is the most characteristic measurement of randomized networks. what a team’s “unique style” is. In the present work In the present work we ellaborate on [5] by ex- we analyse passing sequences at the player level, us- tending the flow motif analysis to a player level. We ing the different passing frequencies as a “digital fin- start by breaking down all possible 3-passes motifs gerprint” of a player’s style. The resulting numbers into all the different variations resulting from labelling provide an adequate feature set which can be used a distinguished node in the motif, resulting on a to- in order to construct a measure of similarity between tal of 15 different 3-passes motifs at the player level players. Armed with such a similarity tool, one can (stemming from the 5 motifs for teams). -

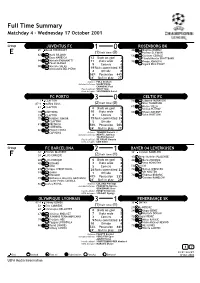

E 1 0 3 0 F 2 1

Full Time Summary Matchday 4 - Wednesday 17 October 2001 Group JUVENTUS FC ROSENBORG BK 25' David TREZEGUET 1046' in Dagfinn ENERLY (1)half time (0) out Hassan EL FAKIRI E in 62' Mark IULIANO in out 59' Christer GEORGE Enzo MARESCA 12 Shots on goal 2 out Harald Martin BRATTBAKK in 84' Michele PARAMATTI 11 Shots wide 4 in out 75' Frode JOHNSEN Pavel NEDVED 9 Corners 6 out Sigurd RUSHFELDT 90' in Marcelo SALAS out Alessandro DEL PIERO 19 Fouls committed 15 4 Offside 0 56% Possession 44% 34' Ball in play 27' Referee: POLL Graham Assistant referees: SHARP Philip CANADINE Paul Fourth official: WILEY Alan UEFA delegate: VERTONGEN Karel FC PORTO30 CELTIC FC 1' CLAYTON 56' in Lubomir MORAVCIK 45'+1 MÁRIO SILVA (2)half time (0) out Alan THOMPSON 61' CLAYTON 67' in Momo SYLLA 8 Shots on goal 0 out Stilian PETROV 10' CÔSTINHA 10 Shots wide 5 88' in Shaun MALONEY 19' CLAYTON 4 Corners 5 out John HARTSON 75' in RUBENS JUNIOR 15 Fouls committed 24 out CLAYTON 5 Offside 3 81' in FREDRICK 50% Possession 50% out CÔSTINHA 24' Ball in play 23' 86' in PAULO COSTA out CAPUCHO Referee: TEMMINK René H.J. Assistant referees: MEINTS Jantinus TALENS Berend Fourth official: DE GRAAF Hennie UEFA delegate: COX Eddie Group FC BARCELONA BAYER 04 LEVERKUSEN 12' Patrick KLUIVERT 2132' Carsten RAMELOW 38' LUIS ENRIQUE (2)half time (1) F 45' Diego Rodolfo PLACENTE 20' LUIS ENRIQUE 6 Shots on goal 5 46' in Boris ZIVKOVIC out 48' in GERARD 3 Shots wide 6 Jens NOWOTNY out XAVI 5 Corners 4 53' LUCIO 69' Philippe CHRISTANVAL 28 Fouls committed 22 76' in Zoltan SEBESCEN out -

Habitat Inmobiliaria Están Concebidas Para Disfrutar De Sus Espacios Habitat Domus, Tercera Promoción De Habitat Inmobiliaria En Entrenúcleos

EL NAZARENO 24 DE OCTUBRE DE 2019 • AÑO XXV • Nº 1.179 PERIODICO SEMANAL INDEPENDIENTE DECANO DE LA PRENSA GRATUITA DE ANDALUCÍA o o o o o o o o El Tiempo JUEVES M: 22 m: 9 VIERNES M: 27 m: 11 SÁBADO M: 27 m: 10 DOMINGO M: 29 m: 13 www.periodicoelnazareno.es El sol lucirá toda la jornada Máximas en aumento Cielos despejados Intervalos nubosos El periódico ‘El Nazareno’ Artículos de cumple 25 años Peluquería y Estética Visítanos Un cuarto de siglo siendo la publicación más leída de Dos Hermanas e Infórmate de l periódico ‘El Nazareno’, de- tado nunca a su cita semanal con todos con motivo de esta efeméride. En la nuestro programa cano de la prensa gratuita de los nazarenos, siendo la publicación primavera de 2020 se celebrará el acto de puntos EAndalucía, celebra su XXV ani- más leída en Dos Hermanas. Este año oficial de la conmemoración de sus Avda. Reyes Católicos, 80 versario. Durante este tiempo no ha fal- se realizarán diferentes actividades Bodas de Plata. t. 954 72 79 52 C/ Botica, 25 t. 954 72 74 63 ELECTRO 93 RUEDA TV Reparación de TV y Aparatos Electrónicos REBAJAS Montaje de Antenas todo el año Montaje y venta de en electrodomésticos Aires Acondicionados y productos de descanso www.electrodomesticoslowcost.com C/ Melliza, 3 Avda. Adolfo Suárez, 44 Tel.: 955 67 52 00 Tel. 955 98 55 34 Dos Hermanas vivió el domingo una nueva edición de su Romería de Valme. Tel. 685 80 53 02 Tel.: 659 94 65 40 NAZARENA DE SEGUROS TOLDOS CHAMORRO HOGAR • DECESOS • AUTOS TOLDOS LA BUENA SOMBRA PERSIANAS Le atendemos en: MOSQUITERAS C/ Nuestra Señora de Valme, 10 FABRICACIÓN, VENTA Y REPARACIÓN. -

P18 Layout 1

THURSDAY, APRIL 24, 2014 SPORTS United break with tradition in Moyes sacking LONDON: By sacking David Moyes as ever, the board decided that it could no in November 1986, Moyes’s job was to The emphasis now will be on finding “I think there is a way of decency manager after less than a season in longer stand by and watch Ferguson’s take command of the juggernaut that a manager with a proven track-record at with dealing with people,” he said. charge, Manchester United contravened empire crumble, regardless of the his predecessor had built. the highest level of the European game “Football managers now just get tossed the principles explicitly laid out by his instructions he had left behind. Ferguson hoped the structures he capable of undoing the damage that around, chucked about, disregarded, illustrious predecessor Alex Ferguson. Had Moyes seen out his six-year con- had put in place would allow Moyes- Moyes has inflicted. While Ryan Giggs rubbished. Decent men, good men, just Ferguson was granted a three-and-a- tract, he would have become United’s who failed to win a trophy in his 11 will take charge of the first team in the get thrown away. And that’s not just half-year grace period before winning third longest-serving post-war manager, years at Everton-to slot seamlessly into interim, the names being linked with David Moyes, that’s all the way through the first of his 38 trophies as United behind only Ferguson and United’s oth- place, thereby enabling United to main- the job on a permanent basis-Louis van football.” manager, in 1990, and he expected his er great Scottish figurehead, Matt tain a tradition of appointing promising, Gaal, Diego Simeone, Jurgen Klopp- The move also met with disapproval successor, who he hand-picked himself, Busby. -

Uefa Champions League 2011/12 Season Match Press Kit

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 2011/12 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT FC Barcelona FC BATE Borisov Group H - Matchday 6 Camp Nou, Barcelona Tuesday 6 December 2011 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................3 Match facts........................................................................................................................4 Squad list...........................................................................................................................6 Head coach.......................................................................................................................8 Match officials....................................................................................................................9 Fixtures and results.........................................................................................................10 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................14 Competition facts.............................................................................................................16 Team facts.......................................................................................................................17 Legend............................................................................................................................19