Mushroom Harvesting Ants in the Tropical Rain Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

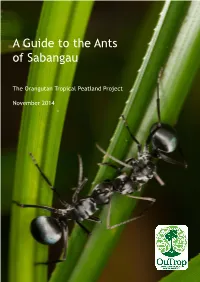

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project November 2014 A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau All original text, layout and illustrations are by Stijn Schreven (e-mail: [email protected]), supple- mented by quotations (with permission) from taxonomic revisions or monographs by Donat Agosti, Barry Bolton, Wolfgang Dorow, Katsuyuki Eguchi, Shingo Hosoishi, John LaPolla, Bernhard Seifert and Philip Ward. The guide was edited by Mark Harrison and Nicholas Marchant. All microscopic photography is from Antbase.net and AntWeb.org, with additional images from Andrew Walmsley Photography, Erik Frank, Stijn Schreven and Thea Powell. The project was devised by Mark Harrison and Eric Perlett, developed by Eric Perlett, and coordinated in the field by Nicholas Marchant. Sample identification, taxonomic research and fieldwork was by Stijn Schreven, Eric Perlett, Benjamin Jarrett, Fransiskus Agus Harsanto, Ari Purwanto and Abdul Azis. Front cover photo: Workers of Polyrhachis (Myrma) sp., photographer: Erik Frank/ OuTrop. Back cover photo: Sabangau forest, photographer: Stijn Schreven/ OuTrop. © 2014, The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project. All rights reserved. Email [email protected] Website www.outrop.com Citation: Schreven SJJ, Perlett E, Jarrett BJM, Harsanto FA, Purwanto A, Azis A, Marchant NC, Harrison ME (2014). A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project, Palangka Raya, Indonesia. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of OuTrop’s partners or sponsors. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project is registered in the UK as a non-profit organisation (Company No. 06761511) and is supported by the Orangutan Tropical Peatland Trust (UK Registered Charity No. -

Digging Deeper Into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning Across Two Continents

diversity Article Digging Deeper into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning across Two Continents Mickal Houadria * and Florian Menzel Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution, Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz, Hanns-Dieter-Hüsch-Weg 15, 55128 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Soil fauna is generally understudied compared to above-ground arthropods, and ants are no exception. Here, we compared a primary and a secondary forest each on two continents using four different sampling methods. Winkler sampling, pitfalls, and four types of above- and below-ground baits (dead, crushed insects; melezitose; living termites; living mealworms/grasshoppers) were applied on four plots (4 × 4 grid points) on each site. Although less diverse than Winkler samples and pitfalls, subterranean baits provided a remarkable ant community. Our baiting system provided a large dataset to systematically quantify strata and dietary specialisation in tropical rainforest ants. Compared to above-ground baits, 10–28% of the species at subterranean baits were overall more common (or unique to) below ground, indicating a fauna that was truly specialised to this stratum. Species turnover was particularly high in the primary forests, both concerning above-ground and subterranean baits and between grid points within a site. This suggests that secondary forests are more impoverished, especially concerning their subterranean fauna. Although subterranean ants rarely displayed specific preferences for a bait type, they were in general more specialised than above-ground ants; this was true for entire communities, but also for the same species if they foraged in both strata. Citation: Houadria, M.; Menzel, F. -

Turf Insects

Ants O & T Guide [T-#01] Carol A. Sutherland Extension and State Entomologist Cooperative Extension Service z College of Agriculture and Home Economics z October 2006 With over 100 ant species in New Mexico, nursery below ground in harvester and fire ants are probably the most familiar and ant colonies. These require 10-14 days to most numerous insects found in turf, complete development. Æ During the ornamental plantings and elsewhere. Only summer, most adult ants probably three species of this abundant group of complete development from egg to adult insects will be described here. Harvester in 6-8 weeks during the summer. and southern fire ants are common in our turf. Red imported fire ant (RIFA) is an invasive, exotic species and a threat to New Mexico agriculture, public health and safety. Metamorphosis: Complete Mouth Parts: Chewing (larvae, adults) Pest Stage: Adults Scientifically: Ants are members of the Red imported fire ant worker, Solenopsis insect order Hymenoptera, Family invicta. Photo: April Noble, www.antweb.org, Formicidae. www.forestryimages.org Typical Life Cycle: Eggs are incubated in Ants are social insects living in colonies of the nursery area of the mound, close to the several hundred to many thousands of surface where the soil is sun warmed. Æ individuals. In its simplest form, a single Larvae are kept in the nursery area where mated queen produces all of the eggs. growing conditions are maintained at Nearly all of these are devoted to optimal levels. All of these stages are production of workers, sterile females tended, fed and protected by worker ants. -

The Coexistence

Myrmecological News 20 37-42 Vienna, September 2014 Discovery of a second mushroom harvesting ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Malayan tropical rainforests Christoph VON BEEREN, Magdalena M. MAIR & Volker WITTE Abstract Ants have evolved an amazing variety of feeding habits to utilize diverse food sources. However, only one ant species, Euprenolepis procera (EMERY, 1900) (Formicidae: Formicinae), has been described as a specialist harvester of wild- growing mushrooms. Mushrooms are a very abundant food source in certain habitats, but utilizing them is expected to require specific adaptations. Here, we report the discovery of another, sympatric, and widespread mushroom harvesting ant, Euprenolepis wittei LAPOLLA, 2009. The similarity in nutritional niches of both species was expected to be accom- panied by similarities in adaptive behavior and differences due to competitive avoidance. Similarities were found in mush- room acceptance and harvesting behavior: Both species harvested a variety of wild-growing mushrooms and formed characteristic mushroom piles inside the nest that were processed continuously by adult workers. Euprenolepis procera was apparently dominant at mushroom baits displacing the smaller, less numerous E. wittei foragers. However, inter- specific competition for mushrooms is likely relaxed by differences in other niche dimensions, particularly the temporal activity pattern. The discovery of a second, widespread mushroom harvesting ant suggests that this life style is more common than previously thought, at least in Southeast Asia, and has implications for the ecology of tropical rainforests. Exploitation of the reproductive organs of fungi likely impacts spore development and distribution and thus affects the fungal community. Key words: Social insects, ephemeral food, niche differentiation, sporocarp, fungivory, Malaysia, obligate mycophagist, fungal fruit body. -

Evolution of Colony Characteristics in the Harvester Ant Genus

Evolution of Colony Characteristics in The Harvester Ant Genus Pogonomyrmex Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Christoph Strehl Nürnberg Würzburg 2005 - 2 - - 3 - Eingereicht am: ......................................................................................................... Mitglieder der Prüfungskommission: Vorsitzender: ............................................................................................................. Gutachter : ................................................................................................................. Gutachter : ................................................................................................................. Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: .............................................................................. Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am: ............................................................................. - 4 - - 5 - 1. Index 1. Index................................................................................................................. 5 2. General Introduction and Thesis Outline....................................................... 7 1.1 The characteristics of an ant colony...................................................... 8 1.2 Relatedness as a major component driving the evolution of colony characteristics.................................................................................................10 1.3 The evolution -

Description of a New Genus of Primitive Ants from Canadian Amber

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 8-11-2017 Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Leonid H. Borysenko Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Borysenko, Leonid H., "Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (2017). Insecta Mundi. 1067. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/1067 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0570 Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Leonid H. Borysenko Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes AAFC, K.W. Neatby Building 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, K1A 0C6, Canada Date of Issue: August 11, 2017 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Leonid H. Borysenko Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Insecta Mundi 0570: 1–57 ZooBank Registered: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C6CCDDD5-9D09-4E8B-B056-A8095AA1367D Published in 2017 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. -

Seed Predation on Slickspot Peppergrass by The

SEED PREDATION ON SLICKSPOT PEPPERGRASS BY THE OWYHEE HARVESTER ANT By Joshua P. White A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology Boise State University May 2009 The thesis presented by Joshua P. White entitled “Seed Predation on Slickspot Peppergrass by the Owyhee Harvester Ant” is hereby approved: ________________________________________________ Ian C. Robertson Date Advisor _______________________________________________ Stephen J. Novak Date Committee Member _______________________________________________ Peter Koetsier Date Committee Member ________________________________________________ John R. Pelton Date Graduate Dean ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. Ian Robertson for all the advice and time he put in helping me to reach this point. Thank you also to my committee Dr. Steve Novak and Dr. Peter Koetsier for their comments and advisement during the degree process. Thanks you guys for all the help and understanding. A special thank you must go to my family for putting up with me over the last three years while I completed my degree. I would also like to thank Wyatt Williams and Quentin Tuckett who gave me excellent advice on not only the best way to complete my thesis but also prepared me for the process of graduate school. I would also like to thank Dana Quinney, Marjorie McHenry, Jay Weaver and Bill Clark for their ongoing assistance with this project, and Janet Nutting, Kyle Koffin and Justin Stark for their volunteer efforts in the field. The Idaho Army National Guard, Sigma Xi, and the Department of Biological Sciences at Boise State University provided funding for my thesis research. -

The Ecology of Nest Movement in Social Insects

EN57CH15-McGlynn ARI 31 October 2011 8:2 The Ecology of Nest Movement in Social Insects Terrence P. McGlynn Department of Biology, California State University Dominguez Hills, Carson, California 90747; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012. 57:291–308 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on absconding, ant, emigration, migration, nomadism, relocation September 9, 2011 The Annual Review of Entomology is online at Abstract ento.annualreviews.org Social insect colonies are typically mobile entities, moving nests from one This article’s doi: Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012.57:291-308. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org location to another throughout the life of a colony. The majority of social in- by California State University - Dominguez Hills on 12/13/11. For personal use only. 10.1146/annurev-ento-120710-100708 sect species—ants, bees, wasps, and termites—have likely adopted the habit Copyright c 2012 by Annual Reviews. ! of relocating nests periodically. The syndromes of nest relocation include All rights reserved legionary nomadism, unstable nesting, intrinsic nest relocation, and adven- 0066-4170/12/0107-0291$20.00 titious nest relocation. The emergence of nest movement is a functional response to a broad range of potential selective forces, including colony growth, competition, foraging efficiency, microclimate, nest deterioration, nest quality, parasitism, predation, and seasonality. Considering the great taxonomic and geographic distribution of nest movements, assumptions re- garding the nesting biology of social insects should be reevaluated, including our understanding of population genetics, life-history evolution, and the role of competition in structuring communities. 291 EN57CH15-McGlynn ARI 31 October 2011 8:2 INTRODUCTION It is a popular misconception that social insect colonies are sessile entities. -

Seed Preference in a Desert Harvester Ant, Messor Pergandei

Seed preference in a desert harvester ant, Messor pergandei Tonia Brito-Bersi1, Emily Dawes1, Richard Martinez2, Alexander McDonald1 University of California, Santa Cruz1, University of California, Riverside2 ABSTRACT Optimal foraging theory states that foragers maximize their energy intake by minimizing the energy expended to collect their food. The harvester ant, Messor pergandei, provides a model system to study foraging energy expenditure due to their dependable group foraging behavior. Exploring seed preference could give us further insight into how their harvesting affects the surrounding vegetation and ecosystem as a whole. Choice trials were conducted on M. pergandei using three native seeds and one non- native food source to determine ant foraging activity for each food type. Additionally, a choice trial involving Encelia seeds and bract were conducted to determine the preference for seed predation versus organic matter collection. Our results showed that Encelia and wheat had the most ant activity. For our second trial, we found that M.pergandei visited Encelia bract more than Encelia seed. Our findings suggest that M. pregandei display a previously undocumented preference for bract and they are willing to forgo other food options that have higher lipid and nutrient content to collect it. This could provide further insight into their overall role in the desert ecosystem as they may be assisting Encelia in seed dispersal. Keywords: Messor pergandei, Encelia, Colorado Desert, optimal foraging theory INTRODUCTION harsh abiotic factors such as low food resources. Individuals that optimize According to optimal foraging theory, foraging efficiency by selecting food types species are expected to maximize energy that are highly nutritious and readily gain while minimizing costs of foraging available will have greater chance of survival. -

Red Harvester Ants Bastiaan M

E-402 4-06 Red Harvester Ants Bastiaan M. Drees* ed harvester ants are one of the more Life cycle noticeable and larger ants in open areas in Texas. Eleven species in this group of ants Winged males and females swarm, couple and R mate, especially following rains. Winged forms (genus Pogonomyrmex) are known from the state. are larger than worker ants. Males soon die and However, harvester ants are not nearly as com- females seek a suitable nesting site. After drop- mon today as they were during the earlier 1900s. ping her wings, the queen ant digs a burrow and The decline, particularly in the eastern part of produces a few eggs. Larvae hatch from eggs and the state, has caused some alarm because these develop through several stages (instars). Larvae ants serve as a major source of food for the are white and legless, shaped like a crookneck rapidly disappearing and threatened Texas squash with a small distinct head. Pupation horned lizard. occurs within a cocoon. Worker ants produced by the queen ant begin caring for other develop- Description ing ants, enlarge the nest and forage for food. 1 1 Worker ants are ⁄4 to ⁄2 inch long and red to Pest status dark brown. They have squarish heads and no spines on the body. There are 22 species of har- Worker ants can give a painful, stinging bite, vester ants in the United States, 10 of which are but are generally reluctant to attack. Effects of found in Texas. Seven of these species are found the bite can spread along lymph channels and only in far west Texas. -

A S H I F T in Seed Harvesting by Ants Following Argentine a N T I N Va S I O N

VIE ET MILIEU - LIFE AND ENVIRONMENT, 2007, 57 (1/2) : 75-81 A S H I F T IN SEED HARVESTING BY ANTS FOLLOWING ARGENTINE A N T I N VA S I O N J. OLIVERAS*, J. M. BAS, C. GÓMEZ Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Girona, Campus de Montilivi s/n, 17071 Girona, Spain *corresponding author: [email protected] HARVESTER ANTS A B S T R A C T. – The effect of A rgentine ant (Linepithema humile) invasion on the dispersal - INVASION predation balance of non-myrmecochorous seeds by ants and vertebrates is analyzed. T h r e e LINEPITHEMA HUMILE NON-MYRECOCHOROUS SEEDS Papilionaceae, Calicotome spinosa, Psoralea bituminosa, and S p a rtium junceum, were studied. SEED DISPERSAL The seeds were made available in field trials during 48 hour periods using ant and vertebrate SEED PREDATION exclusions in zones invaded by L. humile and non-invaded zones. The A rgentine ant invasion resulted in the displacement of most of the native ant species, including the single seed predator ant in the non-invaded zone, Messor bouvieri. C o n s e q u e n t l y, the level of seed removal by ants was lower in the invaded zone for the three seed species. This could produce two opposite e ffects for the plant: a positive reduction of seed predation and a negative loss of seed dispersal due to diszoochory (the seed dispersal performed by seed eating ants). The three studied species s u ffered different intensities of seed removal by ants in the non-invaded zone, so they would be a ffected to varying degrees after the invasion. -

Zootaxa, Taxonomic Revision of the Southeast Asian Ant Genus

Zootaxa 2046: 1–25 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Taxonomic Revision of the Southeast Asian Ant Genus Euprenolepis JOHN S. LAPOLLA Department of Biological Sciences, Towson University. 8000 York Road, Towson, Maryland 21252 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The taxonomy of Euprenolepis has been in a muddled state since it was recognized as a separate formicine ant genus. This study represents the first species-level taxonomic revision of the genus. Eight species are recognized of which six are described as new. The new species are E. echinata, E. maschwitzi, E. thrix, E. variegata, E. wittei, and E. zeta. Euprenolepis antespectans is synonymized with E. procera. Three species are excluded from the genus and transferred to Paratrechina as new combinations: P. helleri, P. steeli, and P. stigmatica. A morphologically based definition and diagnosis for the genus and an identification key to the worker caste are provided. Key words: fungivory, Lasiini, Paratrechina, Prenolepis, Pseudolasius Introduction Until recently, virtually nothing was known about the biology of Euprenolepis ants. Then, in a groundbreaking study by Witte and Maschwitz (2008), it was shown that E. procera are nomadic mushroom- harvesters, a previously unknown lifestyle among ants. In fact, fungivory is rare among animals in general (Witte and Maschwitz, 2008), making its discovery in Euprenolepis all the more spectacular. Whether or not this lifestyle is common to all Euprenolepis is unknown at this time (it is known from at least one other species [V. Witte, pers. comm.]), but a major impediment to the study of this fascinating behavior has been the inaccessibility of Euprenolepis taxonomy.