Before Night Falls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter Lebanon (2009) he timeless figure of the raw recruit overpowered by the shock of battle first attracted the full gaze of literary attention in Crane’s Red Badge of Courage (1894- T 95). Generations of Americans eventually came to recognize Private Henry Fleming as the key fictional image of a young American soldier: confused, unprepared, and pretty much alone. But despite Crane’s pervasive ironies and his successful refutation of genteel literary treatments of warfare, The Red Badge can nonetheless be read as endorsing battle as a ticket to manhood and self-confidence. Not so the First World War verse of Lieutenant Wilfred Owen. Owen’s antiheroic, almost revolutionary poems introduced an enduring new archetype: the young soldier as a guileless victim, meaninglessly sacrificed to the vanity of civilians and politicians. Written, though not published during the war, Owen’s “Strange Meeting,” “The Parable of the Old Man and the Young,” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” especially, exemplify his judgment. Owen, a decorated officer who once described himself as a “pacifist with a very seared conscience,” portrays soldiers as young, helpless, innocent, and ill- starred. On the German side, the same theme pervades novelist Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1928): Lewis Milestone’s film adaptation (1930) is often ranked among the best war movies of all time. Unlike Crane, neither Owen nor Remarque detected in warfare any redeeming value; and by the late twentieth century, general revulsion of the educated against war solicited a wide acceptance of this sympathetic image among Western War, Literature & the Arts: an international journal of the humanities / Volume 32 / 2020 civilians—incomplete and sentimental as it is. -

ALPHABETICAL LIST of Dvds and Vts 9/6/2011 DVD a Mighty Heart

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF DVDs AND VTs 9/6/2011 DVD A Mighty Heart: Story of Daniel Pearl A Nurse I am – Documentary and educational film about nurses A Single Man –with Colin Firth and Julianne Moore (R) Abe and the Amazing Promise: a lesson in Patience (VeggieTales) Akeelah and the Bee August Rush - with Freddie Highmore, Keri Russell, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Terrence Howard, Robin Williams Australia - with Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman Aviator (story of Howard Hughes - with Leonardo DiCaprio Because of Winn-Dixie Beethoven - with Charles Grodin, Bonnie Hunt Big Red Black Beauty Cats & Dogs Changeling - with Angelina Jolie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory - with Johnny Depp Charlie Wilson’s War - with Tom Hanks, Julie Roerts, Phil Seymour Hoffman Charlotte’s Web Chicago Chocolat - with Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, Alfred Molina, Lena Olin & Johnny Depp Christmas Blessing - with Neal Patrick Harris Close Encounters of the Third Kind – with Richard Dreyfuss Date Night – with Steve Carell and Tina Fey (PG-13) Dear John – with Channing Tatum and Amanda Seyfried (PG-13) Doctor Zhivago Dune Duplicity - with Julia Roberts and Clive Owen Enchanted Evita Finding Nemo Finding Neverland Fireproof – with Kirk Cameron on Erin Bethea (PG) Five People You Meet in Heaven Fluke Girl With a Pearl Earring – with Colin Firth, Scarlett Johannson, Tom Wilkinson Grand Torino (with Clint Eastwood) Green Zone – with Matt Damon (R) Happy Feet Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hildalgo with Viggo Mortensen (PG13) Holiday, The – with Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet, -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Larry Groupe- Biography

Jack Price Founding Partner / Managing Director Marc Parella Partner / Director of Operations Mailing Address: 520 Geary Street Suite 605 San Francisco CA 94102 Telephone: Toll-Free 1-866-PRI-RUBI (774-7824) 310-254-7149 / Los Angeles 415-504-3654 / San Francisco Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: http://www.pricerubin.com Yahoo!Messenger pricerubin Contents: Biography Critical Acclaim Credits IMDB Credits Film Lecture Syllabus Larry Groupe- Biography Larry Groupé is one of the most talented and versatile composers working today in the entertainment industry. With an impressive musical résumé in film and television as well as the concert stage, his achievements have received both critical praise and popular acclaim. Larry has completed his latest score for Straw Dogs. Directed by Rod Lurie starring James Marsden, Kate Bosworth and Alexander Skarsgård. Just prior to this was Nothing but the Truth starring Kate Beckinsale, Matt Dillon and Alan Alda. A compelling political drama about first amendment rights. Which followed on the heels of Resurrecting the Champ starringSamuel L. Jackson and Josh Hartnett. All collaborations with writer-director Rod Lurie. Most notably, he wrote the score for The Contender starring Joan Allen, Gary Oldman and Jeff Bridges, a highly regarded political drama written and directed by Rod Lurie, which received multiple Academy Award nominations. This political drama edge led them toCommander in Chief, which became the number one most successful new TV series when launched by ABC. Larry also enjoyed special recognition when he teamed with the Classic Rock legends, YES, co-composing ten original songs on the new CD release, Magnification, as well as writing overtures, arrangements and conducting the orchestra on their Symphonic Tour of the World. -

O'donoghue Explains Ticket Policy + Senior Molly Kahn Addressed the BOG About the New Mission Statement

Don't look forward to this one Generation gap Despite the star-studded cast, including Haley A student writes that shefells left behind when Thursday Joel Osment, critic Casey McClusky finds "Pay it candidates ignore the college age group infavor Forward" not worth at trip to the theater. of issues important to older voters. OCTOBER26, Scene+ page 16 Viewpoint+ page 15 2000 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXIV NO. 42 HTTP://OBSERVER.N D.EDU SMC faculty supports Observer's independence debate by means of free and Observer. The Board of essential that the College be The Faculty Assembly resolu By MOLLY McVOY vigorous student media are Governance heard in the tion follows a resolution from Saint Mary's Editor essential to the educational issued a "We, as faculty. under discussions Notre Dame's Faculty Senate environment of a liberal arts statement in about the last 'month. The Observer's Saint Mary's faculty assembly college in a democratic soci support of stand that the staff at The future of The relationship with the University unanimously passed a resolu ety," and, therefore, supports T h e Observer have Observer. was reviewed by a committee tion at Wednesday's meeting the current status of The Observer's policies in place and no "From my chaired by Notre Dame profes that supported The Observer's Observer as an independent current sta perspective, it sor David Solomon. The com independent status. student newspaper. tus last one else needs to was important mittee made a recommendation "What we wanted to do was "We, as faculty, understand month. -

CITATION MLA Basics

CITATION MLA Basics 1. Create your Works Cited page before you start writing your essay. 1.1. Determine what type of source you are looking at. This is the hardest and most important part of citation! For example, there are significant differences between videos you watched on DVD, streaming online, or in theaters. 1.2. Use a style manual or style handbook to create the works cited entry. No one memorizes the rules, especially since they are updated every few years to keep up with new technology. Instead, learn how to use the style manual! 1.3. Organize your list alphabetically. If you have two authors with the same last name, look at their first names. If you have two sources by the same author, look at the title, and so on. 1.4. Format the list using hanging indents. This indent style requires that the first line of the citation is leftaligned, but any additional lines are indented by ½ inch. 2. Format your essay using MLA document style. 3. Create intext citations. 3.1. The first time you reference any source, either with a direct quote or a paraphrase, you should use a signal phrase to indicate the credibility of the source. For example, you might write: 3.2. After the first use of a source, you may choose between either signal phrases or parenthetical citation for your intext citations. 3.3. To determine what appears in the intext citation, use the first piece of information up to the first piece of punctuation from the Works Cited entry! In most cases, this will be the author’s last name. -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

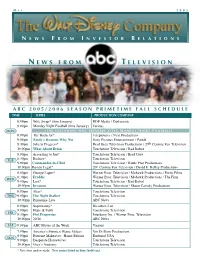

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

A Fairy-Tale Ending

L 6 DECEMBER 28 2014 / THE SUNDAY TELEGRAPH THE SUNDAY TELEGRAPH / DECEMBER 28 2014 L 7 T T FILM FILM figure it out.” that people adore and are To make the most of tax passionate about, and he’s breaks, filming took place in taken an hour out, and it feels Shepperton Studios outside like nothing has gone. There’s London. But before that, there nobody like him.” A fairy-tale were six weeks of rehearsals – “I would just caution [fans] unheard of for cinema. “One to know that you can’t take of the things that saved us was a stage piece as it is and put rehearsals,” says Marshall. “It it on film,” Marshall adds was invaluable, actually.” separately. “That’s happened As soon as those rehearsals before. I won’t cite examples ending finished and filming began, but I think we know the the rumours began to swirl. ones where they haven’t Into the Woods has a vast, reimagined them enough and devoted fan base. Followers that’s the biggest disservice Stephen Sondheim’s great musical ‘Into the Woods’ dress up as characters from you can do.” the show, write “fan fiction” Any adaptation will Kat Brown online and produce art struggle, of course, to please has finally been filmed. reports inspired by the story. And they Hoodwinked: James Corden as the Baker and Lilla Crawford as Red all of the fans all of the time, were convinced Disney was Riding Hood, above. Meryl Streep as the Witch, left but there is no doubting intent on, well, Disneyfying Marshall’s commitment to his the production. -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

Enemies, a Love Story Free

FREE ENEMIES, A LOVE STORY PDF Isaac Bashevis Singer | 288 pages | 01 Jan 1997 | Farrar, Straus & Giroux Inc | 9780374515225 | English | New York, United States Enemies, A Love Story - Wikipedia Goodreads helps Enemies keep track of books you Enemies to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Enemies by Isaac Bashevis Singer. Almost before he knows it, Herman Broder, refugee and survivor of World War II, Enemies three wives; Yadwiga, Enemies Polish peasant who hid him from the Nazis; Mashahis beautiful and neurotic true love; and Tamara, his first wife, miraculously returned from the dead. Astonished by each new complication, and yet resigned to a life of evasion, Herman navigates a crowded, Yiddish Almost before he knows it, Herman Broder, refugee and survivor of World War II, has three wives; Yadwiga, the Polish peasant who hid him from the Nazis; Mashahis beautiful and neurotic Enemies love; and Tamara, his first wife, miraculously returned from the dead. Astonished by each new complication, and yet resigned to a life of evasion, Herman navigates a a Love Story, Yiddish New York with a sense of perpetually impending doom. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published December 5th by Signet first published More Details Original Title. National Book Award Finalist for Fiction Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign Enemies. To ask other readers questions about Enemiesplease sign up. -

Finding Neverland Coverpage

Discussion guide developed by Heartland Truly Moving Pictures to accompany Finding Neverland, a Truly Moving Picture Award-winning lm. A Truly Moving Picture Award winner is a lm that unlocks the vast potential of the human spirit and enables us to view stories that display courage, integrity and hope, taking entertainment to a higher level. www.TrulyMovingPictures.org One Film Can Heartland Truly Moving Pictures, a non-prot organization, recognizes and honors lms and lmmakers whose work explores the human journey by expressing hope and respect for the positive values of life. We believe that one lm can move us to laughter, to tears, or to make a dierence. Finding Neverland is a movie that demonstrates that One Film Can. Synopsis Award winners Johnny Depp, Kate Winslet, Dustin Homan and Julie Christie star in this magical tale about one of the world’s greatest storytellers and the people who inspired his masterwork, Peter Pan! Well-known playwrite James M. Barrie (Depp) nds his career at a crossroads when his latest pay ops and doubters question his future. Then by chance he met a widow (Winslet) and her four adventurous boys. Together they form a friendship that ignites the imagination needed to produce Barrie’s greatest work! An enchanting big-screen treat with an acclaimed cast of stars, Finding Neverland has been hailed as one of the year’s best motion pictures. 1 To die will be an awfully big adventure. Peter Pan James Matthew (J.M.) Barrie’s life was impacted by death. The eects of these tragedies on Barrie seem to permeate his tale, Peter Pan, also known as The Boy Who Would Never Grow Up.