Analyzing the Roles of Country Image, Nation Branding, and Public Diplomacy Through the Evolution of the Modern Olympic Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passion and Glory! Spectacular $Nale to National Series

01 Cover_DC_SKC_V2_APP:Archery 2012 22/9/14 14:25 Page 1 AUTUMN 2014 £4.95 Passion and glory! Spectacular $nale to National Series Fields of victory At home and abroad Fun as future stars shine Medals galore! Longbow G Talent Festival G VI archery 03 Contents_KC_V2_APP:Archery 2012 24/9/14 11:44 Page 3 CONTENTS 3 Welcome to 0 PICTURE: COVER: AUTUMN 2014 £4.95 Larry Godfrey wins National Series gold Dean Alberga Passion and glory! Spectacular $nale to National Series Wow,what a summer! It’s been non-stop.And if the number of stories received over the past few Fields of victory weeks is anything to go by,it looks like it’s been the At home and abroad same for all of us! Because of that, some stories and regular features Fun as future have been held over until the next issue – but don’t stars shine Medals galore! worry,they will be back. Longbow G Talent Festival G VI archery So what do we have in this issue? There is full coverage of the Nottingham Building Society Cover Story National Series Grand Finals at Wollaton Hall, including exclusive interviews with Paralympians John 40 Nottingham Building Society National Series Finals Stubbs and Matt Stutzman.And, as many of our young archers head off to university,we take a look at their options. We have important – and possibly unexpected – news for tournament Features organisers, plus details about Archery GB’s new Nominations Committee. 34 Big Weekend There have been some fantastic results at every level, both at home and abroad.We have full coverage of domestic successes as well the hoard of 38 Field Archery international medals won by our 2eld, para and Performance archers. -

Paul Ziffren Sports Resource Center of the Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles

Journal of Sport History, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer, 1991) Paul Ziffren Sports Resource Center of the Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles. 2141 West Adams Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90118. Dr. Wayne Wilson, (213) 730-9696 Founded more than fifty years ago on October 15, 1936 under the name Helms Athletic Foundation, the Paul Ziffren Sports Resource Center is on the fast track to becoming one of the most important sports’ libraries in the world. Indeed, it is the only sports resource center of its kind in the United States which 306 Film, Media, and Museum Reviews has in addition to its sports’ focus, an ambitious yet well-organized acquisition philosophy. Housed in a visually pleasing edifice, its collections include, a variety of archival materials, scholarly journals, historically significant pho- tographs, annual sport guides, an increasing number of oral histories of southern Californian Olympians, an unparalleled collection of coaching vid- eos, the Avery Brundage Collection, and most importantly over 3,500 volumes of archival Olympic publications. In 1930, W. R. “Bill” Schroeder conceived the idea of providing a museum Interior of the Paul Ziffren Sports Resource Center. Courtesy Paul Ziffren Sports Resource Center of the Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles. 307 Journal of Sport History, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer, 1991) which would not only honor great athletes, but would also provide a gathering place for scholars and laypersons alike, to view, ponder and discuss, that subject which has fascinated the peoples of the world since the beginning of time, sport. The idea became a reality when Paul Helms, owner of Helms Bakery in Culver City, California agreed to acquire modest headquarters in the William May Garland Building in downtown Los Angeles. -

The Olympian Trail Around Much Wenlock in the Footsteps of William Penny Brookes the Olympian Trail Around Much Wenlock in the Footsteps of William Penny Brookes

The Olympian Trail Around Much Wenlock In the footsteps of William Penny Brookes The Olympian Trail Around Much Wenlock In the footsteps of William Penny Brookes Start Start at the Wenlock Museum near the town square in High Street. The Trail begins and ends at the Museum, where a fine collection of Olympian artefacts are on display, illustrating the significant role of Much Wenlock in the revival of the modern Olympic Games. N L O C E K Using this Trail Guide and map W follow the bronze markers set in O 100 L the ground. Discover the sites L I Y A and buildings associated with M R P T I A N William Penny Brookes, founder of the Wenlock Olympian Society, organisers of the annual Games since 1850. Learn of the benefits Dr Brookes brought to the town during the 19th century. Parts of the Trail have limited access - please see Guide and Map. Walkers are advised that they follow the Trail at their own risk. The 2km (1 1/4 mile) route crosses roads, footpaths, fields and steps. Depending on walking pace, the Trail takes around one hour. Wenlock Olympian Trail commissioned in 2000, completed 2001 In May 2012, the Olympic Torch was carried by WOS President, Jonathan Edwards, and through Much Wenlock by WOS Vice President, John Simpson (pictured), on its way to the 2012 London Olympic Games. The Olympian Trail Around Much Wenlock 1867 In the footsteps of William Penny Brookes The first Wenlock Olympian Games were held in 1850 for ‘every grade of man’. -

2014 Cal State L.A. Golden Eagles Baseball • Www .Csulaathletics.Com

2014 Cal State L.A. Golden Eagles Baseball • 1 www.CSULAathletics.com 2 CORPORATE PARTNERS THE GOLDEN EAGLES WISH TO THANK THE FOLLOWING: in-n-out.com sierraacura.com www.CSULAathletics.com mixedchicks.net sizzler.com doubletree.com pepsi.com 2014 Cal State L.A. Golden Eagles Baseball • FOR MORE INFORMATION ON BECOMING A GOLDEN EAGLE CORPORATE PARTNER, PLEASE CONTACT THE DIVISION OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS, AT (323) 343-3080 OR ONLINE AT CSULAATHLETICS.COM 2014 CSULA BASEBAll TEAM # Name Pos. B/T. Ht. Wt. Yr. Hometown/High School Last School 1 Matt Sanchez INF R/R 6-0 180 Sr. Granada Hills / Kennedy HS L.A. Pierce College 2 Andrew Montanari INF L/R 6-0 165 Jr. Santa Monica / Santa Monica HS Cuesta College 3 Niko Garcia INF L/R 5-9 160 Sr. Van Nuys / Cleveland HS L.A. Mission College 4 Casey Ryan IF/OF R/R 5-10 170 Sr. Burbank / Notre Dame HS L.A. Valley College 5 David Trejo INF R/R 5-10 190 Jr. Ventura / St. Bonaventura HS 7 Reed Reznicek RHP R/R 6-2 210 Jr. Vista / Rancho Buena Vista HS Indiana 8 Geoff Schuller OF R/R 6-2 170 Jr. Mission Viejo / Mission Viejo HS Santa Ana JC 9 Steven Luna 1B L/L 6-1 220 Sr. Long Beach / Lakewood HS West L.A. College 10 Manny Acosta INF R/R 6-3 210 Sr. South El Monte / South El Monte HS 13 Greg Humbert RHP/C L/R 5-10 180 Fr. Bellflower / Gahr HS 2014 Cal State L.A. -

A Context for the Early Wenlock Olympian Games Hugh Farey —

Football, Cricket and Quoits A context for the early Wenlock Olympian Games Hugh Farey — n Monday 25 February 1850, ten years after the England,2 and also by contemporary interest in the dis O founding of the Wenlock Agricultural Reading covery of the site of Olympia, but neither of these are Society, and nearly twenty since Dr William Penny reflected to any great extent in the games as they actually Brookes had set up his practice in the town, the Olympian began. Although all the events at Wenlock were indeed Class of the Society was established, for “the promotion of described in Strutts book, it was so comprehensive that the moral, physical and intellectual improvement of the it would be more remarkable if they were not. More sur inhabitants of the Town & Neighbourhood of Wenlock prisingly, Strutt only refers to the Olympic/Olympian and especially of the Working Classes, by the encour Games four times, twice in connection with wrestling, agement of out-door recreation, and by the award of once describing the management of a foot-race, and once, Prizes annually at public meetings for skill in Athletic in a poem, he assumes to allude to “tennice, or the balloon exercises and proficiency in intellectual and industrial ball”. Robert Dovers Games, at Chipping Camden in the attainments.”1 Whether this was solely Brookess idea, Cotswolds, are given fair mention in the introduction, why it was thought necessary, or advisable, and how the but they are not referred to as Olimpick (as they are Olympian name was chosen is not stated. -

2012 Cal State L.A. Golden Eagles Men's Soccer

2012 Cal State L.A. Golden Eagles Men’s Soccer CORPORATE PARTNERS THE GOLDEN EAGLES WISH TO THANK THE F OLLOWING : sizzler.com chipotle.com in-n-out.com sierraacura.com mixedchicks.net doubletree.com pepsi.com FOR MORE IN F ORMATION ON BECOMING A GOLDEN EAGLE CORPORATE PARTNER , PLEASE CONTACT THE DIVISION O F INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS , AT (323) 343-3080 OR ONLINE AT CSULAATHLETICS .COM 1 www.csulaathletics.com 2012 CSULA ROSTER No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. Hometown High School Previous College 0 Steven Barrera GK 6-0 Fr. Bellflower Millikan HS 00 Tyler Hoffman GK 6-0 Fr. Tracy Tracy HS 1 Waleed Cassis GK 6-1 So. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada ESP Omers-Deslauries 3 Andy Lopez D 6-1 Sr. Sylma Sylmar HS L.A. Mission College 4 Samuel Olsson D 5-10 Fr. Falkenberg, Sweden Falkenbergs Gymnasieskola 5 Sergio Talome MF 5-8 Fr. Los Angeles Salesian HS 6 Oscar Carrillo MF 5-6 Jr. Bell Gardens Bell Gardens HS Mt. San Antonio College 7 Miguel Hernandez F 5-7 Jr. Long Beach Cabrillo HS Cerritos College 8 Jordan Payne F 5-10 So. Georgetown, Canada Christ the King HS Cal State Bakersfield 9 Rosario Bras F 5-10 Sr. Guadalupe Righetti HS Allan Hancock College 10 Erik Vargas MF 5-8 Sr. Chula Vista Hilltop HS 11 Antti Arvola F 5-9 Sr. Espoo, Finland University of New Hampshire 12 Daniel Rodriguez D 5-3 Jr. Oxnard Pacifica HS Santa Barbara CC 13 Isaac Briviesca D 5-10 Jr. Oceano Arroyo Grande HS Allan Hancock College 14 Luis Trujillo F 5-8 Fr. -

Sportler Des Jahres Seit 1947

in Baden-Baden Highlights 1 IMPRESSUM Herausgeber Internationale Sport-Korrespondenz (ISK) Objektleitung Beate Dobbratz, Thomas R. Wolf Redaktion Matthias Huthmacher, Sven Heuer Fotos augenklick bilddatenbank GmbH, Perenyi, dpa, Wenlock Olympian Society, Jürgen Burkhardt Konzeption, Herstellung PRC Werbe-GmbH, Filderstadt Sponsoring Lifestyle Sport Marketing GmbH, Filderstadt Anzeigen Stuttgart Friends Ein starker Ostwind . .46–47 INHALT Leichtathletik-EM als TV-Renner . .48–50 Grit Breuer geht durch dick und dünn . .52 Gehaltskürzungen, Prämienstreichungen . .54–55 3 . .Die Qual der Wahl Interview mit Dr. Steinbach . .56–58 4 . .Der VDS-Präsident „Illbruck Challenge“, Germany . .60 6–7 . .Bilder des Jahres Hockeyherren weltmeisterlich . .62 8–9 . .Zeitraffer 2002 Schnellboote auf dem Guadalquivir . .64 10–12 . .Stammgäste in Baden-Baden Mit Pferden spricht man deutsch . .66–67 14–15 . .Super Games in SLC Zuschauen wieder gefragt . .68–69 16–18 . .35 Medaillen made in Germany Vor 30 Jahren siegte Wolfermann . .70 20 . .Frau der Tat: Verena Bentele Gestatten, Heine, Sportlerin des Jahres 1962 . .72 22–24 . .Die schönsten Flüge Velobörse . .74 26–28 . .Tatemae in Fernost Juniorsportler als Überflieger . .76 30–31 . .Preis der Fitness Wenlock Olympian Games . .78 32 . .Vorbilder gesucht Sportler des Jahres seit 1947 . .80–84 34 . .Der Fußballer des Jahres Claudia und die Natur . .88 36–38 . .Goldwoge bei der Schwimm-EM Schumi und die Rekorde . .90 40 . .Als Franzi die Luft wegblieb Happy Birthday . .92 42 . .Basketball-Krimi Ausblick 2003 . .94 44 . .Handball wieder „in“ Ehrengäste . .96–100 3 DIE QUAL DER WAHL ENDET IN EINER PARTY MIT CHAMPIONS Wenn gewählt wird, bilden sich tiefe Gräben. Das war bei Sei’s drum. -

National~ Pastime

'II Welcome to baseball's past, as vigor TNP, ous, discordant, and fascinating as that ======.==1 of the nation whose pastime is cele brated in these pages. And to those who were with us for TNP's debut last fall, welcome back. A good many ofyou, we suspect, were introduced to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) with that issue, inasmuchas the membership of the organization leapt from 1600 when this column was penned last year to 4400 today. Ifyou are not already one of our merry band ofbaseball buffs, we ==========~THE-::::::::::::================== hope you will considerjoining. Details about SABR mem bership and other Society publications are on the inside National ~ Pastime back cover. A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY What's new this time around? New writers, for one (excepting John Holway and Don Nelson, who make triumphant return appearances). Among this year's crop is that most prolific ofauthors, Anon., who hereby goes The Best Fielders of the Century, Bill Deane 2 under the nom de plume of "Dr. Starkey"; his "Ballad of The Day the Reds Lost, George Bulkley 5 Old Bill Williams" is a narrative folk epic meriting com The Hapless Braves of 1935, Don Nelson 10 parison to "Casey at the Bat." No less worthy ofattention Out at Home,jerry Malloy 14 is this year's major article, "Out at Home," an exam Louis Van Zelst in the Age of Magic, ination of how the color line was drawn in baseball in john B. Holway 30 1887, and its painful consequences for the black players Sal Maglie: A Study in Frustration, then active in Organized Baseball. -

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 8Th INTERNATIONAL SESSION for EDUCATORS and OFFICIALS of HIGHER INSTITUTES of PHYSICAL EDUCATION 1

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 8th INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR EDUCATORS AND OFFICIALS OF HIGHER INSTITUTES OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION 10-17 JULY 2008 PROCEEDINGS ANCIENT OLYMPIA 8H DOE003s018.indd 3 12/17/09 12:06:10 PM Commemorative seal of the Session Published by the International Olympic Academy and the International Olympic Committee 2009 International Olympic Academy 52, Dimitrios Vikelas Avenue 152 33 Halandri, Athens GREECE Tel.: +30 210 6878809-13, +30 210 6878888 Fax: +30 210 6878840 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ioa.org.gr Editor: Assoc. Prof. Konstantinos Georgiadis, IOA Honorary Dean Production: Livani Publishing Organization ISBN: 978-960-14-2120-9 8H DOE003s018.indd 4 12/17/09 12:06:11 PM INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 8th INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR EDUCATORS AND OFFICIALS OF HIGHER INSTITUTES OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION SPECIAL SUBJECT: YOUTH OLYMPIC GAMES: CHILDREN AND SPORT ANCIENT OLYMPIA 8H DOE003s018.indd 5 12/17/09 12:06:11 PM 8H DOE003s018.indd 6 12/17/09 12:06:11 PM EPHORIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY (2008) President Minos X. KYRIAKOU Vice-President Isidoros KOUVELOS Members Lambis V. NIKOLAOU (IOC Vice-President) Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS Antonios NIKOLOPOULOS Evangelos SOUFLERIS Panagiotis KONDOS Leonidas VAROUXIS Georgios FOTINOPOULOS Honorary President Juan Antonio SAMARANCH Honorary Vice-President Nikolaos YALOURIS Honorary Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS 7 8H DOE003s018.indd 7 12/17/09 12:06:11 PM HELLENIC OLYMPIC COMMITTEE (2008) President Minos X. KYRIAKOU 1st Vice-President Isidoros KOUVELOS 2nd Vice-President Spyros ZANNIAS Secretary General Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS Treasurer Pavlos KANELLAKIS Deputy Secretary General Antonios NIKOLOPOULOS Deputy Treasurer Ioannis KARRAS IOC Member ex-officio Lambis V. -

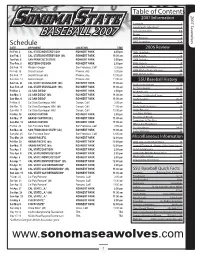

BASEBALL 2007 Roster 5 2007 Preview 6 Schedule 2007 Seawolves 7-14 DATE OPPONENT LOCATION TIME 2006 Review Fri-Feb

Table of Contents 2007 Information 2007 Seawolves Schedule 1 Head Coach John Goelz 2 Assistant Coaches 3-4 BASEBALL 2007 Roster 5 2007 Preview 6 Schedule 2007 Seawolves 7-14 DATE OPPONENT LOCATION TIME 2006 Review Fri-Feb. 2 CAL STATE MONTEREY BAY ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm 2006 Highlights 16 Sat-Feb. 3 CAL STATE MONTEREY BAY (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am 2006 Results 16 Tue-Feb. 6 SAN FRANCISCO STATE ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm 2006 Statistics 17-19 Thu-Feb. 8 WESTERN OREGON ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm 2006 Honors 19 Sat-Feb. 10 Western Oregon San Francisco, Calif 2:00 pm 2006 CCAA Standings 20 Fri-Feb. 16 Grand Canyon Phoenix, Ariz 5:00 pm 2006 All-Conference Honors 20 2006 CCAA Leaders 21 Sat-Feb. 17 Grand Canyon (dh) Phoenix, Ariz 12:00 pm Sun-Feb. 18 Grand Canyon Phoenix, Ariz 11:00 am SSU Baseball History Sat-Feb. 24 CAL STATE STANISLAUS* (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am Yearly Team Honors 22 Sun-Feb. 25 CAL STATE STANISLAUS* (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am All-Time Awards 22-23 Fri-Mar. 2 UC SAN DIEGO* ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm All-Americans 24 Sat-Mar. 3 UC SAN DIEGO* (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am All-Time SSU Baseball Team 25 Sun-Mar. 4 UC SAN DIEGO* ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am Yearly Leaders 26-27 Fri-Mar. 9 Cal State Dominguez Hills* Carson, Calif 2:00 pm Records 28-30 Sat-Mar. 10 Cal State Dominguez Hills* (dh) Carson, Calif 11:00 am Yearly Team Statistics 30 Sun-Mar. -

Tutkielma Olli Rastas Marraskuu 2016

CITIUS, ALTIUS, FORTIUS - OLYMPIALIIKE JA KANSAINVÄLINEN POLITIIKKA KESÄOLYMPIAKISOJEN 1948-1988 VALOSSA TARKASTELTUNA Turun Yliopisto Yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunta Politiikan tutkimuksen laitos Pro Gradu -tutkielma Olli Rastas Marraskuu 2016 Turun yliopiston laatujärjestelmän mukaisesti tämän julkaisun alkuperäisyys on tarkastettu Turnitin OriginalityCheck -järjestelmällä. TURUN YLIOPISTO Politiikan tutkimuksen laitos / Yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunta OLLI RASTAS: Citius, altius, fortius – olympialiike ja kansainvälinen politiikka kesäolympiakisojen 1948 – 1988 valossa tarkasteltuna Pro Gradu -tutkielma, 107 s., 7 liites. Poliittinen historia Marraskuu 2016 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Tämän tutkimuksen tavoitteena on selvittää, miten nykyaikainen olympialiike syntyi ja miten se on kasvanut nykyiseen laajuuteensa sekä miten kansainvälinen politiikka on olympiakisoihin vaikuttanut. Tutkimuksessa pyritään selvittämään, mitkä ovat olleet olympialiikkeen kannalta merkittävimmät boikotit kesäolympialaisissa, mitkä maat ovat kisoja boikotoineet ja mikä on ollut boikottien syynä. Kansainväliseen olympialiikkeeseen vaikuttaneiden poliittisten tekijöiden ohella tarkastellaan kesäolympiakisojen isäntäkaupungin valintaa ja suurvaltojen menestystä toisen maailmansodan jälkeisissä kisoissa vuosina 1948 - 1988. Tutkimuksen primäärilähteenä ovat KOK:n suomalaisjäsenten J.W. Rangellin, Paavo Honkajuuren, Peter Tallbergin ja Pirjo Häggmanin arkistot sekä aiheesta kirjoitettu -

British Olympism in Retrospect

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF OLYMPIC HISTORIANS Bsmmhi O m m m ËMmMMKmr Is the future more of the same? Don Anthony 009 is the 200th anniversary of the birth of Wenlock’s paper this year to honour Gutsmuths. On the same plat 2Dr. William Penny Brookes and Shrewsbury’s Charles form receiving the same degree was UK Prime Minister Darwin. A feature on “The origin of the Olympian William Ewart Gladstone (W.E.G.) Gladstone was bom species” might thus be my most relevant title -..but this in Liverpool—the son of Scots Sir John Gladstone and can await its moment in time. For the moment I want his wife Anne Robertson. Gladstone, who had married merely to skate over the fascinating history of how the a Welsh lady and lived at her family’s ancestral home at parts of British Olympism have created to the whole Hawarden, North Wales, was also a noted Hellenist. At and to challenge the reader to consider our future direc his library, now gifted to the nation as Britain’s only resi tions. Here follows a somewhat playful and irreverent dential -library, he had a table for relaxation named “The analysis. Homer Table”. In his valedictory speech at St. Andrews,a paper fifty printed pages long, there are nine pages men Scottish Olympians tioning Olympic matters. It was thus not surprising that It is also 250 years since the birth of Robbie Bums! both Dr. Brookes and the young Pierre de Coubertin What has the Scottish national poet. Robbie Bums, to both sought the views of this unique political Olympian do with the Olympic family you might ask? A tangen thinker! tial relationship I agree but it is quite significant.