Chapter 1-Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Rap and Feng Shui: on Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound

Chapter 25 Rap and Feng Shui: On Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound Jason King ? (body and soul ± a beginning . Buttocks date from remotest antiquity. They appeared when men conceived the idea of standing up on their hind legs and remaining there ± a crucial moment in our evolution since the buttock muscles then underwent considerable development . At the same time their hands were freed and the engagement of the skull on the spinal column was modified, which allowed the brain to develop. Let us remember this interesting idea: man's buttocks were possibly, in some way, responsible for the early emergence of his brain. Jean-Luc Hennig the starting point for this essayis the black ass. (buttocks, behind, rump, arse, derriere ± what you will) like mymother would tell me ± get your black ass in here! The vulgar ass, the sanctified ass. The black ass ± whipped, chained, beaten, punished, set free. territorialized, stolen, sexualized, exercised. the ass ± a marker of racial identity, a stereotype, property, possession. pleasure/terror. liberation/ entrapment.1 the ass ± entrance, exit. revolving door. hottentot venus. abner louima. jiggly, scrawny. protrusion/orifice.2 penetrable/impenetrable. masculine/feminine. waste, shit, excess. the sublime, beautiful. round, circular, (w)hole. The ass (w)hole) ± wholeness, hol(e)y-ness. the seat of the soul. the funky black ass.3 the black ass (is a) (as a) drum. The ass is a highlycontested and deeplyambivalent site/sight . It maybe a nexus, even, for the unfolding of contemporaryculture and politics. It becomes useful to think about the ass in terms of metaphor ± the ass, and the asshole, as the ``dirty'' (open) secret, the entrance and the exit, the back door of cultural and sexual politics. -

Just Dance 4 Xbox 360 Freeboot Скачать Торрент

just dance 4 xbox 360 freeboot скачать торрент just dance 4 xbox 360 freeboot скачать торрент just dance 4 xbox 360 freeboot скачать торрент - Все результаты Just Dance 4 (FREEBOOT) Xbox360 » скачать игры торрент gamesxboxorg/xbox- kinect/10046-just-dance-4-freeboot-xbox360html 11 сент 2015 г - Игра \ Just Dance 4 XBOX360 \ дает возможность каждому Скачать торрент Just Dance 4 ( FREEBOOT ) Xbox360 Just Dance 4 Just Dance 2018 [GOD/FREEBOOT/ENG] » Игры на xbox 360, xbox xboxthornet/xbox_360/xbox360/747-torrent_just-dance-2018-god-freeboot-enght Вместе с Just Dance 2018 на Xbox 360 каждый сможет почувствовать себя Скачать торрент Just Dance 2018 [GOD/ FREEBOOT /ENG] на xbox 360 без Скачать торрентом Just Dance 2018 (FreeBoot) (ENG) Xbox 360 x360-torrentnet/xbox360/197-just-dance-2018-freeboot-eng-xbox-360-kinecthtml В новой игре Just Dance 2018 на Xbox 360 игроков ждет продолжение сaмой мaсштaбной серии музыкaльных видео-игр всех времен! Новая игра Just Xbox 360 :: Just Dance 4 (FREEBOOT) Xbox360 / 609 GB / Xbox 360 games-xboxru/igraphp?id=10067 Похожие 12 окт 2015 г - Just Dance 4 ( FREEBOOT ) Xbox360 / 609 GB / Xbox 360 скачать торрент Новинки игр для Xbox 360 через torrent без регистрации Just Dance 2016 - Скачать игры на xbox 360 и xbox one с торрента xbox- torrentru/xbox_360/3d-xbox360/370-just-dance-2016-region-free-god-enghtml FREE/GOD/ENG] Скачать торрент Just Dance 2016 [REGION FREE/GOD/ ENG] на xbox 360 FreeBoot Язык интерфейса: Английский Тип перевода: Нет Платформа: Xbox 360 Кооперативное прохождение вне сети: 2 - 4 Just Dance -

Animal Crossing

Alice in Wonderland Harry Potter & the Deathly Hallows Adventures of Tintin Part 2 Destroy All Humans: Big Willy Alien Syndrome Harry Potter & the Order of the Unleashed Alvin & the Chipmunks Phoenix Dirt 2 Amazing Spider-Man Harvest Moon: Tree of Tranquility Disney Epic Mickey AMF Bowling Pinbusters Hasbro Family Game Night Disney’s Planes And Then There Were None Hasbro Family Game Night 2 Dodgeball: Pirates vs. Ninjas Angry Birds Star Wars Hasbro Family Game Night 3 Dog Island Animal Crossing: City Folk Heatseeker Donkey Kong Country Returns Ant Bully High School Musical Donkey Kong: Jungle beat Avatar :The Last Airbender Incredible Hulk Dragon Ball Z Budokai Tenkaichi 2 Avatar :The Last Airbender: The Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings Dragon Quest Swords burning earth Iron Man Dreamworks Super Star Kartz Backyard Baseball 2009 Jenga Driver : San Francisco Backyard Football Jeopardy Elebits Bakugan Battle Brawlers: Defenders of Just Dance Emergency Mayhem the Core Just Dance Summer Party Endless Ocean Barnyard Just Dance 2 Endless Ocean Blue World Battalion Wars 2 Just Dance 3 Epic Mickey 2:Power of Two Battleship Just Dance 4 Excitebots: Trick Racing Beatles Rockband Just Dance 2014 Family Feud 2010 Edition Ben 10 Omniverse Just Dance 2015 Family Game Night 4 Big Brain Academy Just Dance 2017 Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer Bigs King of Fighters collection: Orochi FIFA Soccer 09 All-Play Bionicle Heroes Saga FIFA Soccer 12 Black Eyed Peas Experience Kirby’s Epic Yarn FIFA Soccer 13 Blazing Angels Kirby’s Return to Dream -

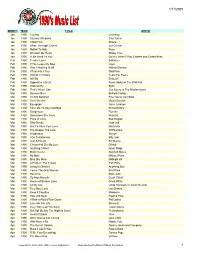

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Assessing Video Games to Improve Driving Skills: a Literature Review and Observational Study

JMIR SERIOUS GAMES Sue et al Review Assessing Video Games to Improve Driving Skills: A Literature Review and Observational Study Damian Sue1; Pradeep Ray1*, PhD; Amir Talaei-Khoei1,2,3*, PhD; Jitendra Jonnagaddala1*; Suchada Vichitvanichphong4 1Asia-Pacific Ubiquitous Healthcare Research Centre (APuHC), University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 2Lab for Agile Information Systems, School of Systems, Management, and Leadership, University of Technology, Sydney, Sydney, Australia 3Research Centre for Human Centered Technology Design (HCTD), University of Technology, Sydney, Sydney, Australia 4Faculty of Arts and Business, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, Australia *these authors contributed equally Corresponding Author: Amir Talaei-Khoei, PhD Lab for Agile Information Systems School of Systems, Management, and Leadership University of Technology, Sydney CB10.04.346, PO Box 123, Broadway, Ultimo NSW 2007 Sydney, Australia Phone: 61 (02) 9514 3 Fax: 61 (02) 9514 3 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: For individuals, especially older adults, playing video games is a promising tool for improving their driving skills. The ease of use, wide availability, and interactivity of gaming consoles make them an attractive simulation tool. Objective: The objective of this study was to look at the feasibility and effects of installing video game consoles in the homes of individuals looking to improve their driving skills. Methods: A systematic literature review was conducted to assess the effect of playing video games on improving driving skills. An observatory study was performed to evaluate the feasibility of using an Xbox 360 Kinect console for improving driving skills. Results: Twenty±nine articles, which discuss the implementation of video games in improving driving skills were found in literature. -

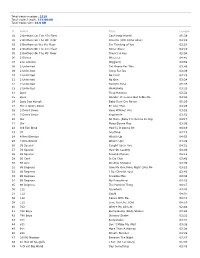

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44 -

2019 Song School Monday

The Song School August 11-15, 2019 • Lyons, CO Schedule and Course Descriptions Sunday, August 11th TO DO LIST: ● Sign up for open stage lottery. All schedules will be posted during lunchtime on Monday in the Blue Heron Tent. (Registration Tent) ● Check master roster information at registration desk for accuracy. 1:00 Campgrounds Opens 2:00 - 5:00 Student Registration Visit us at the Blue Heron Tent and pick up your Song School schedule, wristband, official Song School laminate, reusables, biobag for compostables and other goodies. 5:30 - 6:00 New Student Meet and Greet - Wildflower Pavilion First timer? Meet up with Song School veterans, an instructor or two, ask that burning question, and get some sage advice on how to make your week enjoyable. “Eighty percent of life is just showing up.” – Woody Allen Monday, August 12th TO DO LIST: ● Sign up by 9:15am for open stage lottery. All schedules will be posted during lunchtime in the Blue Heron Tent. ● Check master roster information at registration desk for accuracy. ● Mentoring sheets will go out at 9am each morning for that day’s mentoring sessions. 8:00 - 9:15 Student Registration Visit us at the Blue Heron Tent and pick up your Song School schedule, wristband, official Song School laminate, reusables, biobag for compostables and other goodies. Help yourself to tea or coffee and fruit and pastries next door at the beverage area. Burritos and snacks available at Bloomberries Booth next to bathhouse. Monday p. 2 8:00 - 9:00 Yoga Yogi Heather Hottovy will help celebrate the start of your day with a gentle yoga routine each morning. -

1 Marvin Gaye What's Going on 2 Otis Redding

1 Marvin Gaye What's going on 2 Otis Redding (Sittin' on) The dock of the bay 3 Amy Winehouse Back to black 4 Marvin Gaye Let's get it on 5 Kyteman Sorry 6 Bill Withers Ain't no sunshine 7 Stevie Wonder Superstition 8 John Legend All of me 9 Aretha Franklin Respect 10 Miles Davis So what 11 Sam Cooke A change is gonna come 12 Curtis Mayfield Move on up 13 Al Green Let's stay together 14 James Brown It's a man's man's man's world 15 Michael Jackson Billie Jean 16 Gregory Porter Be good (lion's song) 17 Temptations Papa was a rollin' stone 18 Beyonce ft. Jay-Z Crazy in love 19 Dave Brubeck Take five 20 Earth Wind & Fire September 21 Erykah Badu Tyrone (live) 22 Gregory Porter 1960 what 23 Stevie Wonder As 24 Daft Punk ft. Pharrell & Nile RodgersGet lucky 25 Gladys Knight & The Pips Midnight train to Georgia 26 James Brown Sex machine 27 Michael Kiwanuka Home again 28 Michael Jackson Don't stop 'till you get enough 29 B.B. King The thrill is gone 30 Luther Vandross Never too much 31 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 32 Michael Jackson Off the wall 33 Donny Hathaway A song for you 34 Bobby Womack Across 110th street 35 Earth Wind & Fire Fantasy 36 Bill Withers Grandma's hands 37 Roots ft. Cody Chesnutt The seed (2.0) 38 Billy Paul Me and mrs Jones 39 Marvin Gaye I heard it through the grapevine 40 Etta James At last 41 Chaka Khan I'm every woman 42 Bill Withers Lovely day 43 Giovanca How does it feel 44 Isaac Hayes Theme from Shaft 45 Alicia Keys Empire state of mind (part 2) 46 Chic Le freak 47 Dusty Springfield Son of a preacher man 48 Pharrell Happy -

Cloud Gaming

Cloud Gaming Cristobal Barreto[0000-0002-0005-4880] [email protected] Universidad Cat´olicaNuestra Se~norade la Asunci´on Facultad de Ciencias y Tecnolog´ıa Asunci´on,Paraguay Resumen La nube es un fen´omeno que permite cambiar el modelo de negocios para ofrecer software a los clientes, permitiendo pasar de un modelo en el que se utiliza una licencia para instalar una versi´on"standalone"de alg´un programa o sistema a un modelo que permite ofrecer los mismos como un servicio basado en suscripci´on,a trav´esde alg´uncliente o simplemente el navegador web. A este modelo se le conoce como SaaS (siglas en ingles de Sofware as a Service que significa Software como un Servicio), muchas empresas optan por esta forma de ofrecer software y el mundo del gaming no se queda atr´as.De esta manera surge el GaaS (Gaming as a Servi- ce o Games as a Service que significa Juegos como Servicio), t´erminoque engloba tanto suscripciones o pases para adquirir acceso a librer´ıasde jue- gos, micro-transacciones, juegos en la nube (Cloud Gaming). Este trabajo de investigaci´onse trata de un estado del arte de los juegos en la nube, pasando por los principales modelos que se utilizan para su implementa- ci´ona los problemas que normalmente se presentan al implementarlos y soluciones que se utilizan para estos problemas. Palabras Clave: Cloud Gaming. GaaS. SaaS. Juegos en la nube 1 ´Indice 1. Introducci´on 4 2. Arquitectura 4 2.1. Juegos online . 5 2.2. RR-GaaS . 6 2.2.1. -

Ubisoft® Unveils Just Dance® 3 at E3

UBISOFT® UNVEILS JUST DANCE® 3 AT E3 Best-selling Video Game Franchise Coming To Kinect and Move for First Time LOS ANGELES – June 6, 2011 – Today, during a press conference at the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), Ubisoft® announced the development of Just Dance 3, the third game in the multi-million selling Just Dance franchise. Just Dance 3 marks the debut of the Just Dance series on Kinect™ for Xbox 360® and the PlayStation® Move for PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and the latest installment of the series on the Wii™ system from Nintendo. Developed by Ubisoft Paris and Ubisoft Montreal, Just Dance 3 will be released worldwide on October 11. “The Just Dance brand has truly become a worldwide phenomenon with over 30 million people playing Just Dance,” said Tony Key, senior vice president of sales and marketing at Ubisoft, U.S. “Fans play Just Dance at parties with friends, at home with the family, and as part of an active lifestyle to stay fit or even lose weight. Ubisoft is excited to bring Just Dance 3 to all motion platforms and give even more people the opportunity to enjoy the fun.” Featuring more than 40 tracks across a wide range of musical genres, including pop, hip- hop, rock, R&B, country, disco, funk, and more, Just Dance 3 introduces a number of new game features that take advantage of the unique mechanics of each console. To get the party started, Just Dance 3 includes some of today’s hottest hits as well as classic dance tracks that everyone loves. -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People..