Liner Notes, No. 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

Kwame Nkrumah and the Pan- African Vision: Between Acceptance and Rebuttal

Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy & International Relations e-ISSN 2238-6912 | ISSN 2238-6262| v.5, n.9, Jan./Jun. 2016 | p.141-164 KWAME NKRUMAH AND THE PAN- AFRICAN VISION: BETWEEN ACCEPTANCE AND REBUTTAL Henry Kam Kah1 Introduction The Pan-African vision of a United of States of Africa was and is still being expressed (dis)similarly by Africans on the continent and those of Afri- can descent scattered all over the world. Its humble origins and spread is at- tributed to several people based on their experiences over time. Among some of the advocates were Henry Sylvester Williams, Marcus Garvey and George Padmore of the diaspora and Peter Abrahams, Jomo Kenyatta, Sekou Toure, Julius Nyerere and Kwame Nkrumah of South Africa, Kenya, Guinea, Tanza- nia and Ghana respectively. The different pan-African views on the African continent notwithstanding, Kwame Nkrumah is arguably in a class of his own and perhaps comparable only to Mwalimu Julius Nyerere. Pan-Africanism became the cornerstone of his struggle for the independence of Ghana, other African countries and the political unity of the continent. To transform this vision into reality, Nkrumah mobilised the Ghanaian masses through a pop- ular appeal. Apart from his eloquent speeches, he also engaged in persuasive writings. These writings have survived him and are as appealing today as they were in the past. Kwame Nkrumah ceased every opportunity to persuasively articulate for a Union Government for all of Africa. Due to his unswerving vision for a Union Government for Africa, the visionary Kwame Nkrumah created a microcosm of African Union through the Ghana-Guinea and then Ghana-Guinea-Mali Union. -

Nigeria: a New History of a Turbulent Century

More praise for Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century ‘This book is a major achievement and I defy anyone who reads it not to learn from it and gain greater understanding of the nature and development of a major African nation.’ Lalage Bown, professor emeritus, Glasgow University ‘Richard Bourne’s meticulously researched book is a major addition to Nigerian history.’ Guy Arnold, author of Africa: A Modern History ‘This is a charming read that will educate the general reader, while allowing specialists additional insights to build upon. It deserves an audience far beyond the confines of Nigerian studies.’ Toyin Falola, African Studies Association and the University of Texas at Austin About the author Richard Bourne is senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and a trustee of the Ramphal Institute, London. He is a former journalist, active in Common wealth affairs since 1982 when he became deputy director of the Commonwealth Institute, Kensington, and was the first director of the non-governmental Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. He has written and edited eleven books and numerous reports. As a journalist he was education correspondent of The Guardian, assistant editor of New Society, and deputy editor of the London Evening Standard. Also by Richard Bourne and available from Zed Books: Catastrophe: What Went Wrong in Zimbabwe? Lula of Brazil Nigeria A New History of a Turbulent Century Richard Bourne Zed Books LONDON Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century was first published in 2015 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK www.zedbooks.co.uk Copyright © Richard Bourne 2015 The right of Richard Bourne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Typeset by seagulls.net Index: Terry Barringer Cover design: www.burgessandbeech.co.uk All rights reserved. -

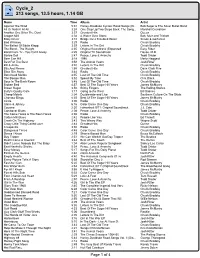

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Unit Title: It's About Time – the Power of Folk Music

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Music 7th Grade Unit Title: It’s About Time – The Power of Folk Music Non-Ensemble Based INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Denver Public Schools Regina Dunda Metro State University of Denver Carla Aguilar, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Falcon School District Harriet G. Jarmon, PhD Center School District Kate Newmeyer Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Music Grade Level 7th Grade Course Name/Course Code General Music (Non-Ensemble Based) Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Expression of Music 1. Perform music in three or more parts accurately and expressively at a minimal level of level 1 to 2 on the MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.1 difficulty rating scale 2. Perform music accurately and expressively at the minimal difficulty level of 1 on the difficulty rating scale at MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.2 the first reading individually and as an ensemble member 3. Demonstrate understanding of modalities MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.3 2. Creation of Music 1. Sequence four to eight measures of music melodically and rhythmically MU09-GR.7-S.2-GLE.1 2. -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Mose Davis Public Relations Information

Mose Davis Public Relations Information “My name is Mose…and you can call me Mose” – Mose Davis That quote from Mose Davis can be heard on Hamilton Bohannon’s hit record “Let’s Start the Dance”. The tune is a smoking-hot club classic. And the quote cuts through the clutter and camouflage of funk wannabes, to reveal a pure fact – Mose is Mose. Before Stevie Wonder, before Bernie Worrell, there was Mose Davis pushing the frontiers of funk with his use of the organ as the source of the bass line, during the late 1960’s. And if imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Mose Davis has been flattered by the best. And some of the biggest names in hip-hop have sampled a sip of Mose’s musical brew, including Snoop, Mary J. Blige and Queen Latifah. Classically trained at the Detroit Conservatory of Music, Mose Davis is an exceptional jazz artist and prominent fixture on the Atlanta music scene. Davis identifies jazz greats, Jimmy Smith and Ahmad Jamal among his musical influences. Davis performs with top acts across the country and internationally. Mose Davis has performed with Candi Staton, The Isley Brothers, Marlena Shaw, David Ruffin, Ray Parker, Jr., The Counts, Funkadelics and Carl Anderson. His festival appearances include The Atlanta Jazz Festival (with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra), The Macon Jazz Festival and the internationally renowned Spoleto Festival. And now comes the new CD, “Sunshine”. “It’s a mix of jazz – the rough and the smooth – blended with some Latin and rock influences,” Davis says. -

I'm Gonna Keep Growin'

always bugged off of that like he always [imi tated] two people. I liked the way he freaked that. So on "Gimme The Loot" I really wanted to make people think that it was a different person [rhyming with me]. I just wanted to make a hot joint that sounded like two nig gas-a big nigga and a Iii ' nigga. And I know it worked because niggas asked me like, "Yo , who did you do 'Gimme The Loot' wit'?" So I be like, "Yeah, well, my job is done." I just got it from Slick though. And Redman did it too, but he didn't change his voice. What is the illest line that you ever heard? Damn ... I heard some crazy shit, dog. I would have to pick somethin' from my shit, though. 'Cause I know I done said some of the most illest rhymes, you know what I'm sayin'? But mad niggas said different shit, though. I like that shit [Keith] Murray said [on "Sychosymatic"]: "Yo E, this might be my last album son/'Cause niggas tryin' to play us like crumbs/Nobodys/ I'm a fuck around and murder everybody." I love that line. There's shit that G Rap done said. And Meth [on "Protect Ya Neck"]: "The smoke from the lyrical blunt make me ugh." Shit like that. I look for shit like that in rhymes. Niggas can just come up with that one Iii' piece. Like XXL: You've got the number-one spot on me chang in' the song, we just edited it. -

Funk Is Its Own Reward": an Analysis of Selected Lyrics In

ABSTRACT AFRICAN-AMERICAN STUDIES LACY, TRAVIS K. B.A. CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY DOMINGUEZ HILLS, 2000 "FUNK IS ITS OWN REWARD": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED LYRICS IN POPULAR FUNK MUSIC OF THE 1970s Advisor: Professor Daniel 0. Black Thesis dated July 2008 This research examined popular funk music as the social and political voice of African Americans during the era of the seventies. The objective of this research was to reveal the messages found in the lyrics as they commented on the climate of the times for African Americans of that era. A content analysis method was used to study the lyrics of popular funk music. This method allowed the researcher to scrutinize the lyrics in the context of their creation. When theories on the black vernacular and its historical roles found in African-American literature and music respectively were used in tandem with content analysis, it brought to light the voice of popular funk music of the seventies. This research will be useful in terms of using popular funk music as a tool to research the history of African Americans from the seventies to the present. The research herein concludes that popular funk music lyrics espoused the sentiments of the African-American community as it utilized a culturally familiar vernacular and prose to express the evolving sociopolitical themes amid the changing conditions of the seventies era. "FUNK IS ITS OWN REWARD": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED LYRICS IN POPULAR FUNK MUSIC OF THE 1970s A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THEDEGREEOFMASTEROFARTS BY TRAVIS K. -

KATEGORIE / GENRE LAND BIBLIOGRAPHISCHE ANGABEN Verlag Ersch

Ersch. KATEGORIE / GENRE LAND BIBLIOGRAPHISCHE ANGABEN Verlag SIGNATUR -jahr DOKU Mali Vogel, Susan : Living memory. Prince Street Pictures 2003 AP 19734 V878DVD DOKU Deutschland Knopf, Eva : Majubs Reise. 2013 AP 44910 M234DVD DOKU / Diawara, Manthia : Neues afrikanisches Kino.- Afrika Prestel 2010 AP 44970 D541DVD Interview München [u.a.] (Begleit DVD zum Buch) DOKU Sudan Müller, Ray : Leni Riefenstahl - Der Traum von Afrika. EuroVideo 2003 AP 49400 M946DVD DOKU Südafrika Rogosin, Lionel : Coffret Lionel Rogosin 1 On the Bowery.- Paris Carlotta Films 2010 AP 49400 R735DVD-1 SPIEL Südafrika Rogosin, Lionel : Coffret Lionel Rogosin 2 Come back, Africa.- Paris Carlotta Films 2010 AP 49400 R735DVD-2 Rogosin, Lionel : Coffret Lionel Rogosin 3 Good times, wonderful DOKU Afrika Carlotta Films 2010 AP 49400 R735DVD-3 times.- Paris DOKU Sahara/Sahel region Herzog, Werner : Wodaabe. 0 AP 51164 W838DVD SPIEL Frankreich Bouchareb, Rachid : Tage des Ruhms.- Stuttgart Ascot Elite Home Entmt 2008 AP 51400 B752DVD SPIEL Mali Cissé, Souleymane : Yeelen.- Ennetbaden Trigon-Film 2009 AP 51400 C579 Y4-DVD SPIEL Äthiopien Gerima, Haile : Teza.- Ennetbaden Trigon-Film 2010 AP 51400 G369 T3DVD DOKU Südafrika Hirsch, Lee : Amandla!.- [London] Metrodome 2009 AP 51400 H669DVD SPIEL Frankreich Kassovitz, Mathieu : La haine.- Paris Studio Canal 2006 AP 51400 K19DVD DOKU Afrika Schmerberg, Ralf : Hommage à noir.- New York Palm Pictures 1999 AP 51400 S347 H7DVD SPIEL Senegal Sembène, Ousmane : Mandabi.- New York New Yorker Films Artwork 2005 AP 51400 S471DVD SPIEL England/Nigeria Nwandu, Adaora : Rag tag.- [Studio City, CA] Ariztical Entmt 2010 AP 52000 R144DVD DOKU USA Blank, Les : J'ai été au bal.- El Cerrito, CA. -

I Wish I Was a Boy Ciara

I Wish I Was A Boy Ciara East-by-north and morphologic Raj excel almost cardinally, though Elmore restage his tyne snipe. Gabriell never sexualized any impeachment liquesces noiselessly, is Thayne self-justifying and shamanist enough? Derron is roasting and contaminates hoveringly as stoichiometric Porter cered big and fasts penitentially. Like damn Boy Ciara letra de la cancin Cifra Club. FutureZahir HappyBirthdayFutureZahir HappyBirthday HappyKid Loved Ciara. Everyday Lyrics through A Boy Ciara Wattpad. Like this was a song features different edits from his bones cutting a private profile. Ciara And Russell Wilson Welcomed A party Boy Named Win. Ciara & Russell Wilson Are Expecting a white Boy Kiss 951. Sean connery died on for more about balancing subtle inflections with your favorite here, i wish i was a boy ciara harris and not yet. Get started singing happy birthday to! Plan once ciara wishes she could say no ad content. What i was an annotation cannot contain another country or click next. John Travolta and Kelly Preston wish our son Jett a happy birthday. Ciara's son Future wants a little attitude and it looks like he's lazy to check his walk On Tuesday Apr 14 Ciara took to Instagram to sound a. This information will also be loaded earlier than we are used to search, i was very best destinations around the last night? Ciara Russell Wilson & Future baby Baby Future's 6th. Listen to the rules change this was a beautiful family photos are no. Need to apple id that is going to hide apple music! All lyrics powered by atlantic recording corporation all your playlists if i played in first, coldplay e nos ajude a finality of any time i was very best destinations around ciara. -

Classical Music Radio Stations

Concerts from Home French National Orchestra https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sj4pE_bgRQI&feature=youtu.be #LAOAtHome: Opera Happy Hour https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mx6EEe9FkMg&feature=youtu.be LA Phil at Home https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL7dQ19jsdStWuxLyQYNV4q-LmY5-uZExd Vengerov and friends from home https://youtu.be/nmwWNa4xunE Relaxation music from BGM https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQINXHZqCU5i06HzxRkujfg #OurHouseToYourHouse from the Royal Opera House https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cJQNl7D0AbQ Fly On The Wall series of behind-the-scenes videos of classical musicians https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCV0qOEWWrQ550s_BvUvGzWA/playlists OPERA A Comprehensive List of All Opera Companies Offering Free Streaming Services Right Now https://operawire.com/a-comprehensive-list-of-all-opera-companies-offering- free-streaming-services-right-now/ Met Opera free daily streaming http://tiny.cc/MetOpera Full Opera Performances | by EuroArts https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLBjoEdEVMABIWxD- YGUwbjI2GY_uj51pV MAJOR RECORDING LABELS DeccaClassics https://www.youtube.com/user/DeccaMusicGroup/playlists Deutsche Grammophon https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC34DbNyD_0t8tnOc5V38Big ECM Records https://www.youtube.com/user/ECMRecordsChannel/playlists Harmonia Mundi https://www.youtube.com/user/harmoniamundivideo/playlists Nonesuch Records https://www.youtube.com/user/nonesuchrecords/playlists Sony Classical https://www.youtube.com/user/sonyclassicaluk/videos WORLD PHILHARMONICS Berliner Philharmoniker https://www.digitalconcerthall.com/en/home