Biograph Theater 2433-43 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

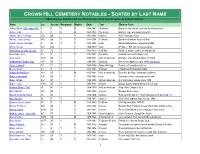

Crown Hill Cemetery Notables - Sorted by Last Name

CROWN HILL CEMETERY NOTABLES - SORTED BY LAST NAME Most of these notables are included on one of our historic tours, as indicated below. Name Lot Section Monument Marker Dates Tour Claim to Fame Achey, David (Dad, see p 440) 7 5 N N 1838-1861 Skeletons Gambler who met his “just end” when murdered Achey, John 7 5 N N 1840-1879 Skeletons Gambler who was hung for murder Adams, Alice Vonnegut 453 66 Y 1917-1958 Authors Kurt Vonnegut’s sister Adams, Justus (more) 115 36 Y Y 1841-1904 Politician Speaker of Indiana House of Rep. Allison, James (mansion) 2 23 Y Y 1872-1928 Auto Allison Engineering, co-founder of IMS Amick, George 723 235 Y 1924-1959 Auto 2nd place 1958 500, died at Daytona Armentrout, Lt. Com. George 12 12 Y 1822-1875 Civil War Naval Lt., marble anchor on monument Armstrong, John 10 5 Y Y 1811-1902 Founders Had farm across Michigan road Artis, Lionel 1525 98 Y 1895-1971 African American Manager of Lockfield Gardens 1937-69 Aufderheide’s Family, May 107 42 Y Y 1888-1972 Musician She wrote ragtime in early 1900s (her music) Ayres, Lyman S 19 11 Y Y 1824-1896 Names/Heritage Founder of department stores Bacon, Hiram 43 3 Y 1801-1881 Heritage Underground RR stop in Indpls Bagby, Robert Bruce 143 27 N 1847-1903 African American Ex-slave, principal, newspaper publisher Baker, Cannonball 150 60 Y Y 1882-1960 Auto Set many cross-country speed records Baker, Emma 822 37 Y 1885-1934 African American City’s first black female police 1918 Baker, Jason 1708 97 Y 1976-2001 Heroes Marion County Deputy killed in line of duty Baldwin, Robert “Tiny” 11 41 Y 1904-1959 African American Negro Nat’l League 1920s Ball, Randall 745 96 Y 1891-1945 Heroes Fireman died on duty Ballard, Granville Mellen 30 42 Y 1833-1926 Authors Poet, at CHC ded. -

Advancing Corrections

| 1 technology re-entry leadership Advancing Corrections 2011 Annual Report INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION Leadership from the top 2 | Governor Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr. “For the Indiana Department of Correction, public safety is always the highest priority and the continual trend of lowering recidivism rates and assuring successful re-entry is critical to that mission. In 2011, the leadership and staff throughout the state have reason to be proud after receiving the coveted ACA’s Golden Eagle Award for the accreditation of all our correctional facilities. I want to commend IDOC for its continued excellence in its service to our state, while finding ways to spend tax dollars more efficiently and effectively.” Table of Contents • Letter from the Commissioner 5 • Executive Staff 6 • Timeline of Progress 18 • Adult Programs & Facilities 30 • Division of Youth Services (DYS) 48 Juvenile Programs & Facilities • Parole Services 58 • Correctional Training Institute (CTI) 66 • PEN Products 70 • Financials & Statistics 76 | 3 Vision As the model of public safety, the Indiana Department of Correction returns productive citizens to our communities and supports a culture of inspiration, collaboration, and achievement. Mission The Indiana Department of Correction advances public safety and successful re-entry through dynamic supervision, programming, and partnerships. Advancing Letter from the Commissioner through Leadership... Bruce Lemmon Commissioner Amanda Copeland Chief of Staff Penny Adams Executive Assistant Aaron Garner Executive Director -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection MS.404

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8w66sh5 No online items Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection MS.404 Debra Roussopoulos University of California, Santa Cruz 2019 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Preston Sawyer Film and Theater MS.404 1 Collection MS.404 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection creator: Sawyer, Preston, 1899-1968 Identifier/Call Number: MS.404 Physical Description: 8 Linear Feet27 boxes Date (inclusive): 1907-1959 Abstract: This collection contains photographs, lobby cards, correspondence, ephemera, and realia. Storage Unit: 1-27 Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. For more information on copyright or to order a reproduction, please visit guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/reproduction-publication. Preferred Citation Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection. MS 404. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Biographical / Historical The Sawyer family of Santa Cruz, California, were avid movie and theater aficionados. The materials in this collection were gathered mainly by Preston Sawyer, and contributed to by Ariel and Gertrude Sawyer. Ariel Sawyer spent time working in Hollywood from 1922-1925. -

Aug. 22-28, 2019

THIS WEEK on the WEB Roncalli football field renamed in honor of longtime high school educator Page 2 BEECH GROVE • CENTER GROVE • GARFIELD PARK & FOUNTAIN SQUARE • GREENWOOD • SOUTHPORT • FRANKLIN & PERRY TOWNSHIPS FREE • Week of August 22-28, 2019 Serving the Southside Since 1928 ss-times.com PAGES 6-7 TIMESOGRAPHY Greenwood’s WAMMfest raises $10,000 for local organizations PAGE 4 A safe place to learn Perry Meridian senior creates one-of-a-kind sensory room for students with special needs HAUNTS & JAUNTS FEATURE FEATURE FEATURE Is there a different body Greenwood solider Greenwood band hosts concert Free family entertainment in John Dillinger’s grave? killed in Ft. Hood, TX of 100s of statewide musicians at BG’s Music on Main Page 5 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 SEE OUR AD ON PAGE 5 Altenheim (Indianapolis/Beech Grove) I am so happy with dad’s care Aspen Trace (Greenwood/Bargersville/Center Grove) and how content he seems. Greenwood Health & Living University Heights Health & Living (Indianapolis/Greenwood) I agree I’m so grateful for CarDon! www.CarDon.us CARDON - EXPERT SENIOR LIVING SOLUTIONS. 2 Week of August 22-28, 2019 • ss-times.com COMMUNITY The Southside Times Contact the Southside THIS Managing Editor on the Have any news tips? Want News Quiz WEEK to submit a calendar event? WEB Have a photograph to share? Call Nancy Price at How well do you know your 698-1661 or email her at Southside community? Roncalli to dedicate Kranowitz named [email protected]. And remember, our news Test your current event football field to Bob Tully president and CEO of Keep deadlines are several days prior to print. -

Legislature a Shallow Talent Pool Former Gov

V14 N43 Thursday, July 9, 2009 Legislature a shallow talent pool Former Gov. Oxley’s painful fall Edgar Whit- underscores shift away comb (left) and U.S. Sen. Evan from Statehouse for Bayh at the Statehouse dur- gubernatorial timber ing Gov. Frank O’Bannon’s By BRIAN A. HOWEY funeral in 2003. INDIANAPOLIS - The sad The two repre- story about the fall of 2008 Demo- sent contrasting cratic lieutenant governor nominee eras when the Dennie Oxley II since February un- Indiana General derscores an emerging Assembly was trend when it comes a gubernato- to power politics: rial breeding The Indiana General ground. (HPI Assembly is losing its Photo by Brian station as a breeding A. Howey) ground for guberna- torial tickets. When Democratic gubernato- 1996 won the rial nominee Jill Long Thompson won the primary in May nominations, with roots going back to the Indiana Senate. 2008, it was the eighth time out of the last 10 nomination In that time frame, the two major parties have slots that went to an individual who didn’t have roots in the relied on two mayors, a congressman, a former congress- Indiana General Assembly. The two exceptions occurred when Lt. Gov. John Mutz in 1988 and Frank O’Bannon in Continued on Page 3 Kenny Rogers session By DAVE KITCHELL LOGANSPORT - Collectively, 151 people played out their hands last Tuesday in the Indiana Statehouse. In the end, they all left with something, which after all is the goal of any card player when they leave the table. “I’m looking forward to maybe Gov. -

2016 IGNITION Festival Release 2016

Press contact: Cathy Taylor/Kelsey Moorhouse Cathy Taylor Public Relations [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 773-564-9564 Victory Gardens Theater Announces Lineup for 2016 IGNITION Festival of New Plays 2016 Festival runs August 5–7, 2016 CHICAGO, IL – Victory Gardens Theater announces the lineup for the 2016 IGNITION Festival of New Plays, including The Wayward Bunny by Greg Kotis; BREACH: a manifesto on race in America through the eyes of a black girl recovering from self-hate by Antoinette Nwandu; EOM (end of message) by Laura Jacqmin; Kill Move Paradise by James Ijames; Gaza Rehearsal by Karen Hartman; and Girls In Cars Underwater by Tegan McLeod. The 2016 Festival runs August 5-7, 2016 at Victory Gardens Theater, located at 2433 N Lincoln Avenue. INGITION’s six selected plays will be presented in a festival of readings and will be directed by leading artists from Chicago. Following the readings, two of the plays may be selected for intensive workshops during Victory Gardens’ 2016-17 season, and Victory Gardens may produce one of these final scripts in an upcoming season. "At Victory Gardens Theater, we bridge Chicago communities through innovative and challenging new plays by giving established and emerging playwrights the time and space to develop their work. This year, we have invited some of the most thrilling playwrights to join our IGNITION Festival,” said Isaac Gomez, Victory Gardens Theater Literary Manager. “Their plays exemplify the current political and cultural zeitgeist of our city and country: the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, race and gender, the modern struggles of fatherhood, the insular world and morality of video gaming, and a woman’s journey to self-love. -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, a Case Study

Katie Walsh Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, A Case Study Abstract William Powell became a star in the 1930s due to his unique brand of suave charm and witty humor—a quality that could only be expressed with the advent of sound film, and one that took him from mid-level player typecast as a villain, to one of the most popular romantic comedy leads of the era. His charm lay in the nonchalant sophistication that came naturally to Powell and that he displayed with ease both on screen and off. He was exemplary of the success of the new kind of star that came into their own during the transition to sound: sharp- or silver-tongued actors who were charming because of their way with words and not because of their silver screen faces. Powell also exercised a great deal of control over his publicity and star image, which is best examined during his short and failed tenure as a Warner Bros. during the advent of his rise to stardom. Despite holding a great amount of power in his billing and creative control, Powell was given a parade of cookie-cutter dangerous playboy roles, and the terms of his contract and salary were constantly in flux over the three years he spent there. With the help of his agent Myron Selznick, Powell was able to navigate between three studios in only a matter of a few years, in search of the perfect fit for his natural abilities as an actor. This experimentation with star image and publicity marked the period of the early 1930s in Hollywood, as studios dealt with the quickly evolving art and technological form, industrial and business practices, and a shifting cultural and moral landscape. -

Chicago Tragedy

LH&RB Newsletter of the Legal History & Rare Books SIS of the American Association of Law Libraries Volume 22 Number 2 Summer 2016 Hog Butcher for the World, Chicago Tragedy: A Guide Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, to Some of the Famous Player with Railroads and the Nation's Freight Handler; and Infamous Law-Related Stormy, husky, brawling, Sites of Chicago City of the Big Shoulders… Mark W. Podvia —Carl Sandburg, Chicago The City of Chicago has had its more than its share of murder, mayhem and disaster. All of these happenings attracted national attention; a few resulted in regulations that have improved health and safety. This is a listing of some of the most well-known Chicago tragedies. You might want to visit some or all of these places during your time in Chicago. Several of these are located within walking distance of the AALL Annual Meeting. Some others can be reached via public transportation. Be aware that not all of these locations are open to the public. Federal Regulations Gone Awry: The Sinking of the SS Eastland Chicago Riverwalk between LaSalle and Clark Streets The SS Eastland, a popular Chicago-based excursion boat, was launched in 1902. Known for its speed, the vessel had a design flaw that made it top-heavy. The problem was worsened following the passage of the Federal Seamen's Act in 1915. The act, adopted is response to the RMS Titanic disaster, required the retrofitting of a complete set of lifeboats on the Eastland. The additional weight made the unstable ship even more dangerous. -

Fimp P *2.22 *244

PAGE 6 THE INDIANAPOLIS TIMES JAN. 5, It* STORY OF JOHN DILLINGER'S BOYHOOD IS TOLD BY THESE PHOTOS CITIZEN-OWNED' UTILITY PLANTS £ I SHOW PROFIT Municipal Light and Power . Plants in ’32 Made ' $212,542.10, Municipally owned utilities re- turned a net profit of $212,542.10 to Indiana towns where they operate and thus aided in keeping them I JEFTr JmmF^aaSg from borrowing from working bal- ances in 1932. This fact is set out in a report on town finances for that year made public today by William P. Cos- grove. ...... state examiner. It was pre- ' ' pared in his office by Albert E. Dickens, statistician. One hundred and forty-two civil towns operate ,waterworks, fifty- three electric plants and thirty both water and electric utilities, the re- port shows. In 1932. these utilities received 51.023.6C7.50 in operating revenues and disbursed 5811.065.40 for oper- ating and maintenance. Expenses Decrease In the total of 423 Indiana towns, the governmental cost for 1932 was $3,461,003.47, the reiiort shows. This was $593,623.52 or 14.6 per cent less than was expended in 1931. Tax re- ceipts were 26.4 per cent less, how- ever, being the lowest since 1922. CAPITOL They decreased 21.4 per cent from Suits, Topcoats, Overcoats 1 the previous year and were $253.- 1 006.39 less than disbursements, ne- cessitating inroads on working bal- ances to make up the deficiency in revenue. School functions were maintained in but eighty of the incorporated towns at a cost of $2,101,915.