Grazing Potential and Management: Knapweeds Are Generally Unpalatable to Livestock, Especially When Mature. Nutritive Value of R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petroleum Coke and Plants: Impact on Growth and Physiology

Petroleum coke and plants: Impact on growth and physiology By: Colin Keiji Nakata A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of; MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Botany University of Manitoba Winnipeg, MB., Canada March 14th,2007 Copyright A 2007 by Colin Keiji Nakata THE TJNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STT]DIES ****:* COPYRIGHT PERMISSION Petroleum coke and Plants: Impact on growth and PhYsiolog¡r BY Colin Keiji Nakata A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Colin Keiji Nakata @2007 permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesigpracticum,io the National Library of Canada to microfîlm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of túe film, aná to University Microfilms rnc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solóty for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied owner. as permitied by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright l1 Ansrnacr: Greenhouse studies were conducted to determine the effects of coke, a by-product of the oil sand industry, on the emergence, growth and physiology of Triticum aestivum, Deschampsia caespitosa, Calamagr-ostis canadensis, Agropyron trachycaulum, Oryzopsis hymenoides, Fragaria virginiana and Cornus set"icea. Accumulation of potentially toxic elements in plant tissues was also determined. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 CREATING A WILDLIFE FRIENDLY YARD ......................................................................2 With Plant Variety Comes Wildlife Diversity...............................................................2 Existing Yards....................................................................................................2 Native Plants ......................................................................................................3 Why Choose Organic Fertilizers?......................................................................3 Butterfly Gardens...............................................................................................3 Fall Flower Garden Maintenance.......................................................................3 Water Availability..............................................................................................4 Bird Feeders...................................................................................................................4 Provide Grit to Assist with Digestion ................................................................5 Unwelcome Visitors at Your Feeders? ..............................................................5 Attracting Hummingbirds ..................................................................................5 Cleaning Bird Feeders........................................................................................6 -

INDIAN RICEGRASS Erosion Control/Reclamation: One of Indian Ricegrass' Greatest Values Is for Stabilizing Sites Susceptible to Achnatherum Hymenoides Wind Erosion

Plant Guide INDIAN RICEGRASS Erosion control/reclamation: One of Indian ricegrass' greatest values is for stabilizing sites susceptible to Achnatherum hymenoides wind erosion. It is well adapted to stabilization of (Roemer & J.A. Schultes) disturbed sandy soils in mixes with other species. It is naturally an early invader onto disturbed sandy Barkworth sites (after and in concert with needle and thread Plant Symbol = ACHY grass). It is also one of the first to establish on cut and fill slopes. It does not compete well with Contributed By: USDA NRCS Idaho State Office aggressive introduced grasses during the establishment period, but is very compatible with slower developing natives, such as Snake River wheatgrass (Elymus wawawaiensis), bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolata ssp. lanceolata), streambank wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolata ssp. psammophila), western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), and needlegrass species (Stipa spp. and Ptilagrostis spp.). Drought tolerance combined with fibrous root system and fair to good seedling vigor, make Indian ricegrass desirable for reclamation in areas receiving 8 to 14 inches annual precipitation. Wildlife: Forage value is mentioned in the grazing/rangeland/hayland section above. Due to the abundance of plump, nutritious seed produced by Indian ricegrass, it is considered an excellent food source for birds, such as morning doves, pheasants, and songbirds. Rodents collect the seed for winter food supplies. It is considered good cover habitat for small -

An Agricultural Law Research Article the Federal Seed Act: Regulation

University of Arkansas School of Law [email protected] $ (479) 575-7646 An Agricultural Law Research Article The Federal Seed Act: Regulation of Feed Sales and Remedies Available to the See Purchaser by James B. Wadley Originally published in SOUTH DAKOTA LAW REVIEW 27 S. D. L. REV. 453 (1982) www.NationalAgLawCenter.org THE FEDERAL SEED ACT: REGULATION OF SEED SALES AND REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO THE SEED PURCHASER* JAMES B. WADLEY·· INTRODUCTION. 453 NATURE AND SCOPE OF THE FEDERAL SEED ACT................... 454 RESTRICTIONS ON SEED PRODUCERS AND DISTRIBUTORS. 457 Laheling Requirements.......................................... 457 Advertising. .. .. 460 RESTRICTIONS ON IMPORTATION AND STAINING OF SEEDS........... 461 Importation and Staining 0/Seeds. 461 Cert!fied Seed . .. 462 Treated Seed. 463 Record Keeping . 464 REGULATION OF WEED SEEDS....................................... 465 DISCLAIMERS AND WARRANTIES. 467 ENFORCEMENT OF THE FEDERAL SEED ACT. • . • . 472 REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO THE SEED PURCHASER.................... 474 CONCLUSION 475 INTRODUCTION The sale of seed is of particular interest to the farmer. If the farmer receives the wrong seed, or defective seed, the farmer may not discover the error until it is too late to replant. If this occurs, the loss to the farmer in cludes, in addition to the cost of the seed, the value of the lost crop. Simi larly, if the farmer plants seed that is contaminated with undesirable weed seeds, it may take years and countless dollars to eventually rid the farm of the infestation. To protect the farmer, the federal government and state legislatures have adopted statutes regulating the sale and shipment of seeds. I This arti • This article is based in part on a chapter from "Agricultural Law" published by Little, Brown and Company. -

Alternate Crops for Eastern Oregon: Research

ALTERNATE CROPS FOR EASTERN OREGON: RESEARCH 1Stephen Machado, 2Brian Tuck, and 1Christopher Humphreys 1Oregon State University, Columbia Basin Agricultural Research Center, P.O. Box 370, Pendleton, OR 97801. Tel: (541) 278 4416 Email: [email protected] 2Oregon State University, Extension Service, Wasco County, 400 E. Scenic Drive, Suite 2.278, The Dalles, OR 97058. Tel: (541) 296 5494 Email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Crop Page Chickpeas (Cicer arietinum) 4 Lentils (Lens culinaris) 10 Peas (Pisum sativum) 17 Faba beans. (Vicia faba) 24 Linola/Flax. (Linum usitatissimum) 27 Safflower (Carthamus tinctorious) 30 Sunflower (Helianthus annus) 33 Mustard. (Brassica spp.) 36 Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum/sagittatum Moench) 39 Millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) 42 Corn (Zea mays L.) 47 Lupin (L. albus L., L. augustifolius L., L. luteus L., L. 50 mutabalis L., and L. cosentenii L.) Indian Ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides, Oryzopsis 58 hymenoides) Green Needlegrass (Stipa viridula) 64 2 Introduction The Pacific Northwest (PNW) Columbia Plateau is semi-arid with rainfall ranging from 12 to 18 inches. About 70 percent of annual precipitation occurs from November to April during winter and water available to plants during spring and summer depends on how much water is stored in the soil. Because of steep slopes prevalent in the PNW, soil erosion is a major problem in fields that do not have sufficient residue cover. Cropping systems that improve water infiltration and storage, reduce evaporation, and increase water use efficiency of crops on a sustainable basis should be developed. Wheat/fallow rotation is the traditional crop production system in the PNW Columbia Plateau. -

Known High Quality Or Rare Plant Communities and Wetland Ecosystems

Appendix A Upper Middle Mainstem Columbia River Subbasin Plan Known High Quality or Rare Plant Communities and Wetland Ecosystems Table 1 Known high quality or rare plant communitites and wetland ecosystems of the UMM Subbasin, WA. SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Abies amabilis - Tsuga mertensiana cover Pacific silver fir - mountain hemlock type forest Abies amabilis / Achlys triphylla forest Pacific silver fir / vanillaleaf Abies amabilis cover type Pacific silver fir forest Abies grandis / Acer circinatum forest Grand fir / vine maple Abies lasiocarpa / Calamagrostis rubescens Subalpine fir / pinegrass forest Abies lasiocarpa / Ledum glandulosum forest Subalpine fir / glandular labrador-tea Abies lasiocarpa / Rhododendron albiflorum Subalpine fir / cascade azalea woodland Abies lasiocarpa /Vaccinium scoparium Subalpine fir / grouseberry forest Abies lasiocarpa cover type Subalpine fir forest Abies procera cover type Noble fir forest Acer circinatum cover type Vine maple shrubland Alnus viridis ssp. Sinuata shrubland Sitka alder (provisional) SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Artemisia arbuscula / Festuca idahoensis Low sagebrush /Idaho fescue dwarf-shrub herbaceous vegetation Artemisia rigida / Poa secunda dwarf-shrub Stiff sagebrush / Sandberg's bluegrass herbaceous vegetation Artemisia rigida cover type Stiff sagebrush shrubland Artemisia tridentata / Festuca idahoensis Big sagebrush / Idaho fescue shrub herbaceous vegetation Artemisia tridentata cover type Big sagebrush shrubland Artemisia tridentata ssp. Wyomingensis / Wyoming big sagebrush -

Plant Materials Technical Note No

United States Department of Agriculture NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Plant Materials Technical Note No. MT-55 February 2006 PLANT MATERIALS TECHNICAL NOTE WAYNE BERRY COMPARATIVE EVALUATION PLANTING PERFORMANCE SUMMARY 1994-2002 Larry Holzworth, Plant Materials Specialist Joe Fidel, Resource Conservationist Susan Winslow, Agronomist Mark Majerus, Bridger Plant Materials Manager Abstract There is interest in the Northern Great Plains to use warm-season grasses for extending the “green period” for mid- and late-summer grazing and to increase species diversity in the re- vegetation of deteriorated rangelands, mine reclamation, and conservation practices applied through farm bill programs. The Bridger Plant Materials Center (PMC), in cooperation with the Bismarck PMC, the Sidney, Montana Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) field and area office, and Mr. Wayne Berry established a study to evaluate warm-season and cool-season forages in east-central Montana. The Wayne Berry field evaluation planting was established on a dryland site in east-central Montana, to study the adaptation, performance, and use of new native and introduced pasture plants in comparison to commonly used species/cultivars. A replicated warm- and cool-season grass, forb, and shrub study featuring 56 accession/cultivars was planted in May 1994. The plots are four-rows, six meters (19.68 ft) long, and replicated four times in randomized complete blocks. The plots were evaluated for field emergence, plant vigor, basal cover and biomass production over nine years. The best performing cool-season species were Elytrigia intermedia, Elytrigia repens x pseudoroegneria, Agropyron cristatum x desertorum, Pascopyron smithii, and Psathyrostachys juncea. Warm-season grasses and forbs from southern latitudes, i.e., South Dakota, performed better than North Dakota eco-types, supporting the theory that southern eco-types perform better than northern eco-types in northern latitudes. -

Common Names

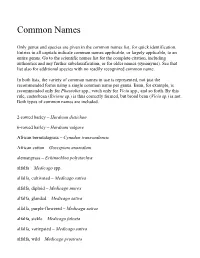

Common Names Only genus and species are given in the common names list, for quick identification. Entries in all capitals indicate common names applicable, or largely applicable, to an entire genus. Go to the scientific names list for the complete citation, including authorities and any further subclassification, or for older names (synonyms). See that list also for additional species with no readily recognized common name. In both lists, the variety of common names in use is represented, not just the recommended forms using a single common name per genus. Bean, for example, is recommended only for Phaseolus spp., vetch only for Vicia spp., and so forth. By this rule, castorbean (Ricinus sp.) is thus correctly formed, but broad bean (Vicia sp.) is not. Both types of common names are included. 2-rowed barley – Hordeum distichon 6-rowed barley – Hordeum vulgare African bermudagrass – Cynodon transvaalensis African cotton – Gossypium anomalum alemangrass – Echinochloa polystachya alfalfa – Medicago spp. alfalfa, cultivated – Medicago sativa alfalfa, diploid – Medicago murex alfalfa, glanded – Medicago sativa alfalfa, purple-flowered – Medicago sativa alfalfa, sickle – Medicago falcata alfalfa, variegated – Medicago sativa alfalfa, wild – Medicago prostrata alfalfa, yellow-flowered – Medicago falcata alkali sacaton – Sporobolus airoides alkaligrass – Puccinellia spp. alkaligrass, lemmon – Puccinellia lemmonii alkaligrass, nuttall – Puccinellia airoides alkaligrass, weeping – Puccinellia distans alsike clover – Trifolium hybridum Altai wildrye -

Seed Selection by Desert Rodents: Implications for Enhancing Seedling Establishment of Indian Ricegrass (Achnatherum Hymenoides)

Western North American Naturalist Volume 76 Number 2 Article 6 7-19-2016 Seed selection by desert rodents: implications for enhancing seedling establishment of Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides) William S. Longland USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Great Basin Rangelands Research Unit, Reno, NV, [email protected] Lindsay A. Dimitri Department of Biology, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Longland, William S. and Dimitri, Lindsay A. (2016) "Seed selection by desert rodents: implications for enhancing seedling establishment of Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides)," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 76 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol76/iss2/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. WesterN North AMericaN Naturalist 76(2), © 2016, pp. 253–258 SEED SELECTION BY DESERT RODENTS: IMPLICATIONS FOR ENHANCING SEEDLING ESTABLISHMENT OF INDIAN RICEGRASS ( ACHNATHERUM HYMENOIDES ) WilliaM S. LoNglaNd 1 aNd LiNdsay A. DiMitri 2 ABSTRACT .— Seeds of MaNy plaNt species are dispersed by seed-cachiNg rodeNts that place groups of seeds iN super - ficially buried scatterhoard caches. A case iN poiNt is INdiaN ricegrass ( Achnatherum hymenoides ), aN iMportaNt forage plaNt oN arid westerN raNgelaNds for which seedliNg recruitMeNt coMes largely froM scatterhoards Made by desert heteroMyid rodeNts. -

Cheatgrass (Bromus Tectorum L) Dominance in the Great Basin Desert: History, Persistence, and Influences to Human Activities

Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L) dominance in the Great Basin Desert: History, persistence, and influences to human activities By: Paul A Knapp Knapp, P.A. (1996) Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L.) dominance in the Great Basin Desert: History, persistence, and influences to human activities. Global Environmental Change 6:37-52. Made available courtesy of Elsevier: http://www.elsevier.com ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Elsevier. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document.*** Abstract: Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L), an exotic annual, is a common, and often dominant, species in both the shadscale and sagebrush-steppe communities of the Great Basin Desert. Approximately 20% of the sagebrush- steppe vegetation zone is dominated by cheatgrass to the point where the establishment of native perennial species is nearly impossible. This paper discusses the historical factors that led to the establishment and dissemination of cheatgrass in the Great Basin, examines the processes that further cheatgrass dominance, provides examples of subsequent Influences of the grass to human activities, and links the ecological history with range condition models. Evidence suggests that cheatgrass was introduced accidentally to the Great Basin as a grain contaminant at the end of the 19th century at the same time that large-scale domestic grazing was occurring. Imported from Mediterranean Europe and central and south-western Asia, seeds of cheatgrass exploited an ecological niche, as no native annual was dominant In the Great Basin. Cattle, sheep, and feral horses facilitated establishment, for they spread the seeds in the same areas that they disturbed. -

Indian Ricegrass Seed Damage and Germination Responses to Mechanical Treatments

Indian ricegrass seed damage and germination responses to mechanical treatments Item Type text; Article Authors Griffith, L. W.; Booth, D. T. Citation Griffith, L. W., & Booth, D. T. (1988). Indian ricegrass seed damage and germination responses to mechanical treatments. Journal of Range Management, 41(4), 335-337. DOI 10.2307/3899391 Publisher Society for Range Management Journal Journal of Range Management Rights Copyright © Society for Range Management. Download date 23/09/2021 16:15:17 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645194 Indian ricegrass seed damage and germination responses to mechanical treatments LARRY W. GRIFFITH AND D. TERRANCE BOOTH AbSttWt Indian ricegrass [Oryzopsis hymenoitb (Ram. and Sctudt.) rubber-lined steel outer-wall by an inside cylinder. This rubbing Ricker] is IIvaluable forage specien in tbe western United States; action dehulls and scarifies the seed. The For&erg Model 2 differs however, low fresh-seed germin8tion bee limited its use in renge- from the For&erg scarifier [used by Zemetra et al. (1983)] which land rcvegetation. Seed damage and germination effects were eval- employs rotating batts to propel the seed against sandpaper. uated on 2 seedlots of ‘Nezpar’ Indlan ricegrass exposed to 3 The Quaker Oats dehuller uses a rapidly rotating impeller to mechanical treatments. The air-gun scarifier and the Quaker Oats throw the seed against the side of a rubber-lined metal cylinder; the dehuller improved germination wherea the For&erg dehuller impact breaks the hull from the seed. decreased germination. Disruption of the seed coat before storage The air-gun scarifier, described by Booth and Griffith (1984), appears to be a practical method of reducing storage time required uses compressed air to shoot individual seeds into an abrasive lined for improved germination of freshly harvested sad. -

48456 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 179 / Tuesday, September 16, 1997 / Rules and Regulations

48456 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 179 / Tuesday, September 16, 1997 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE provisions of the FSA are found in include plant health activities §§ 201.101 through 201.230 (referred to conducted at the Federal level, Animal and Plant Health Inspection below as the regulations). including the seed analysis and Service The responsibility for inspection of laboratory accreditation activities we imported seeds under Title III of the had attributed to Agriculture and Agri- 7 CFR Parts 201 and 361 FSA was transferred from the Food Canada in the proposed rule. [Docket No. 93±126±5] Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) to Therefore, for accuracy, we will refer to the Animal and Plant Health Inspection the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, RIN 0579±AA64 Service (APHIS) by a final rule rather than to Agriculture and Agri- amending the delegations of authority Imported Seed and Screenings Food Canada, throughout this from the Secretary of Agriculture that document. We have also updated the AGENCY: Animal and Plant Health was published in the Federal Register regulations in § 371.7(a) to reflect that Inspection Service, USDA. on September 22, 1982 (47 FR 41725), change. ACTION: Final rule. and effective October 1, 1982. In a proposed rule published in the Discussion of Comments SUMMARY: We are amending the Federal Register on October 4, 1996 (61 Comment: The proposed regulations ``Imported Seed'' regulations by moving FR 51791±51810, Docket No. 93±126±4), refer to an ``official seed analyst,'' which the regulations to a different chapter in we proposed to revise the regulations to is defined as a ``registered member of the Code of Federal Regulations; reflect amendments to the FSA and the the Association of Official Seed establishing a seed analysis program transfer of regulatory authority for Title Analysts'' (AOSA).