Aalborg Universitet Science and Technology Policy Jamison, Andrew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Til Hassan Nur Wardere, MB E-Mail

KØBENHAVNS KOMMUNE Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningen Direktion Til 10. maj 2019 Hassan Nur Wardere, MB Sagsnr. E-mail: [email protected] 2019-0121739 Dokumentnr. 2019-0121739-1 Kære Hassan Nur Wardere Tak for din henvendelse af d. 2. maj 2019, hvor du har stillet spørgs- mål til Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningen vedr. gentagede virksomhedspraktikker. Spørgsmål Hvilke virksomheder i Københavns Kommune har haft samme ar- bejdsløse borgere i virksomhedspraktik ad flere omgange? Hvilket ud- fald har dette haft, er borgerne eksempelvis kommet i job? Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningens svar I perioden fra 4. kvartal 2015 til 3. kvartal 2018 var der 5.996 borgere, som har været i virksomhedspraktik to gange i samme virksomhed 1. Nogle af dem har været i sådan et gentaget forløb mere end én gang. I alt har der i perioden været 6.328 tilfælde af gentagen virksomheds- praktik, hvilket sammensætter sig af 13.784 forløb. Samlet set var der i perioden 58.123 virksomhedspraktikforløb. Det vil sige, at de genta- gede virksomhedspraktikforløb udgør 24 pct. af det samlede antal for- løb i perioden. 13,4 pct. af forløbene er endt med, at borgeren er i job eller uddan- nelse i 2. måned efter forløbet2. For at vise spredningen i, hvor mange gange samme virksomhed har haft gentagede virksomhedspraktikforløb, har forvaltningen inddelt dem i intervaller (set på, hvor mange gange virksomheden har haft en borger i gentagede virksomhedspraktikker): 1 Gentaget virksomhedspraktik er defineret som to virksomhedspraktikker, hvor der er mindre end et år mellem afslutningen på det første forløb og opstart på det andet Direktion forløb i samme virksomhed (afgrænset på p-nummer). -

Vanløse, Ålekistevej - Kastrup St

31 Vanløse, Ålekistevej - Kastrup St. Gyldig fra 13.12.2020 s s u u h . h . d n n å e St åd e St R d n R d . n . r . g t. år t rg t å t ke S g S rke e S g r . j . er t e n . ) t e o S a n t t ) b r o t n r n r p e ve S n s n r S e sb o a b s k S e e e k o a rb spa rke evej m k p r r p t ) lm i p p l i r b e v a n s o r e av a u o r d ) a u s ø h e er ) g r p en) h e e e li g r r jfe l edbli e d o a g t ki n de st v o a g st str øjf d st v v r stp e lø y ed iv y re e o i m e o as l S a J r e o m er o a Ålekist(Sl Vanløse(J St.F V H (T A L P K Å ( V ( F V H (T A L P K — — — — 5.06 5.16 5.20 5.25 5.30 20.06 20.09 20.19 20.26 20.29 20.40 20.44 20.49 20.54 5.03 5.06 5.16 5.23 5.26 5.36 5.40 5.45 5.50 06 09 19 26 29 40 44 49 54 5.23 5.26 5.36 5.43 5.46 5.56 6.00 6.05 6.10 26 29 39 46 49 00 04 09 14 5.43 5.46 5.56 6.03 6.06 6.16 6.20 6.25 6.30 46 49 59 06 09 20 24 29 34 5.57 6.00 6.11 6.18 6.21 6.31 6.35 6.40 6.45 0.06 0.09 0.19 0.26 0.29 0.40 0.44 0.49 0.54 6.11 6.15 6.26 6.33 6.36 6.46 6.50 6.55 7.00 6.18 6.22 6.33 6.40 6.43 6.53 6.57 — — 6.25 6.29 6.40 6.47 6.50 7.00 7.04 7.10 7.15 mandag- fredag mandag - fredag 6.32 6.36 6.47 6.54 6.57 7.07 7.11 — — 6.39 6.43 6.54 7.01 7.04 7.15 7.19 7.25 7.30 6.46 6.50 7.01 7.08 7.11 7.22 7.26 — — 6.53 6.57 7.09 7.16 7.19 7.30 7.34 7.40 7.45 7.00 7.04 7.16 7.23 7.26 7.37 7.41 — — 7.06 7.10 7.22 7.29 7.33 7.45 7.49 7.55 8.00 7.13 7.17 7.29 7.36 7.40 7.52 7.56 — — 7.19 7.23 7.35 7.43 7.47 8.00 8.04 8.10 8.15 7.25 7.29 7.41 7.50 7.54 8.07 8.11 — — 7.32 7.36 7.49 7.58 8.02 8.15 8.19 8.25 8.30 7.40 7.44 7.57 -

Glenten Bygningernes Forskudte Indhold Højder Giver Lejlighederne Et Smukt Lysindfald Og Mange Udsigtspunkter

Glenten Bygningernes forskudte Indhold højder giver lejlighederne et smukt lysindfald og mange udsigtspunkter. 04 "Sweet spot" 06 Drømmen har vinger … 08 Oversigtskort 12 Unik arkitektur 14 Variation og sammenhæng 16 Detaljer fra bygningen 20 Området 30 Plantegningerne 72 Materialeliste 3 JEG ELSKER LIVET I INDRE BY. PÅ STRANDLODSVEJ FÅR JEG Et "sweet spot" LYSET, DE GRØNNE AREALER OG STRANDEN – KUN 10 MIN PÅ CYKEL FRA NYHAVN. DET GIVER i Københavns FØLELSEN AF AT BO I EN SAND LILLE KØBENHAVNSK OASE. Kamila Ewelina Osinka Ny-tilflyttet beboer på Amager hyggelige forhave Hvis Amager er hele Københavns forhave, så er Strandholmen det hyggelige "sweet spot", hvor vi alle elsker at opholde os, fordi der både er læ, hygge, privatliv, sol og en perfekt udsigt. På Strandholmen køber du ikke bare en bolig på X antal m2 med altan. Du køber også billet til et unikt fællesskab af kræsne og kvalitets- bevidste boligkøbere, som på den ene side vil bo mindre end 4 km fra Rådhuspladsen, og som på den anden side ønsker at leve midt i naturen og tæt på rekreative områder som Kløvermarken og Amager Strandpark. Med en bolig i Strandholmen bliver du en del af det karakteristiske aktive lokalmiljø med butikker, foreninger og skoler, som Amager er kendt og elsket for. Med grøn cykelsti ind til city, gode Metro- og busforbindelser samt underjordisk parkering har Strandholmen alt, hvad der skal til for at sikre en gnidningsfri hverdag for moderne urbane individer og aktive familier. 4 Drømmen har vinger … Amager er ikke bare stedet, hvor dine boligdrømme kan få luft under vingerne. -

Endelig Har Nanna Sit Eget Værelse

TÅRNBYTÅRNBY BLADETBLADET NOVEMBER • 2018 NR. 11. NOVEMBER 2018 • 26. ÅRGANG • WWW.TAARNBYBLADET.DK Mange brikker at flytte rundt med 150 elever fra Korsvejens Skole har haft kunstner- besøg Af Terkel Spangsbo På Korsvejens Skole har de i høj grad taget skakken til sig. De fleste elever fra 1. til 9. klasse kender spillet, reglerne og det store antal varianter, som man- ge slet ikke kender til. Hvem kender eksempelvis bondeskak? Det gør eleverne på Korsvejen! Nu er det også synligt for forbipasserende på Tårnbyvej, at her er der en skole med en særlig interesse. Sammen med LÆREREN og KUNSTNEREN har tre årgange skabt 150 skakbrikker, men ikke blot som kopier, men hver brik med sit udtryk. Der er en gravsten, med en spinkel dron- ningekrone - motivet kunne hedde skakmat og sådan er der flere lag i opfattelsen af de en- kelte brikker. Se hele kunstværket på side 14 fungerede upåklageligt, men Endelig har Nanna sit eget værelse så begyndte de hjemlige pro- Tårnby Bladet skriver lige kontakt mellem Tårnby ger ude i det ganske land, der noreret familien Puggaards blemer med at skabe det liv, normalt ikke ledere og vi Kommune og familien Pug- bare tilnærmelsesvis minder ønsker omkring deres hoved- som systemet havde reddet bestræber os på at være gaard på Jacob Appels allé, om forløbet efter familiens kulds ændrede situation. Og Nanna tilbage til. objektive, men i spørgsmå- som har ført til at mindst 94 dengang 13-årige Nanna samtidig har kommunen også Her savnede Morten og let om en del af den kom- af Danmarks 98 kommuner pludseligt og helt -

Byg Mellem Husene

ESTATE ESTATE ESTATE MAGASIN Professionel MAGASIN MAGASIN OM BYGGERI, EJENDOM OG INVESTERING – udgives i samarbejde med erhvervsudlejning | 06 2013 | 6. årgang Nr. CASE: Byggesocietetet 100 procents Nr. 06 | 2013 | 6. årgang finansiering på Søger din virksomhed nye lokaler? - Find dem på www.dal.dk plads med ejendoms- obligationer NYBYGGEDE Se side 42 KONTORER ER BILLIGST – eller er de? Læs artiklen side 54 Opfordring til investorer og udviklere: KONTOR/SHOWROOM KONTOR & LAGER KONTOR KONTOR/UNDERVISNING Store Kongensgade, KBH. K Marielundvej/Hørkær, Herlev Amager Strandpark, KBH. S Vesterbrogade, KBH. V Byg Sag nr. 21024218 Sag nr. 21024003 Sag nr. 21024186 Sag nr. 21024211 Areal fra 151 til 676 m2 Areal fra 146 til 900 m2 Areal fra 50 til 700 m2 / Leje DKK 1.175,-/m2 Areal fra 130 til 504 m2 inkl. P-pladser Stop gratis Leje DKK 950,- pr. m2 Leje fra DKK 300,- til 750,- pr. m2 Perfekte nye lejemål til kontor, café og Momsfri leje DKK 1.050,- pr. m2 2 2 arbejdet i Drift & skatter inkl. i lejen Drift & skatter DKK 34,- pr. m publikumsorienteret serviceerhverv. Drift & skatter DKK 42,- pr. m mellem arkitektbranchen Læs side 30 Skal vi udleje eller sælge din ejendom? husene DAL Erhvervsmægler er specialiseret i salg, udlejning og vurdering af erhvervs- Læs hvordan lejemål og erhvervsejendomme i København og hovedstadsområdet. Vores på side 14 markedsvurdering giver dig overblik, og du får en professionel og dedikeret erhvervsmægler, når du vælger os til opgaven ... Fra Tyskland til renovering DAL Erhvervsmægler Kontakt os på 70 300 555 for en gratis Forbindelsesvej 12 & uforpligtende markedsvurdering af din Læs side 36 2100 København Ø erhvervsejendom. -

Nyt Bynet På Amager Øst Og Amager Vest

Nyt Bynet på Amager - Fra Cityringens åbning i 2019 Movia, Nyt Bynet på Amager Indhold Forslag til den lokale busbetjening 2 Nyt Bynet på Amager Øst og Amager Vest 3 Strategisk busnet fra Cityringens åbning 5 Forslag til lokalt busnet fra Cityringens åbning 9 Adgang til stoppesteder og stationer 19 Movia, Nyt Bynet på Amager Forslag til den lokale busbetjening Om halvandet år åbner den nye Cityring, som løfter hele den kollektive transport i hovedstadsområdet op i international topklasse. I 10 år har anlægsarbejdet stået på, og mange har dagligt mærket, hvor- dan trafikafviklingen har måttet tilpasse sig. Men om under to år tages Cityringen i brug, og borgerne i hovedstadsområdet får en forbedring af den kollektive transport, som der er hårdt brug for. Når Cityringen åbner, bindes den tæt sammen med bus, tog og eksisterende metrolinjer i én sammen- hængende transportorganisme. Byen rykker tættere på omegnen, og omegnen rykker tættere på byen, når mange af de mest benyttede rejseveje får kortere rejsetid og den samlede kapacitet i trans- portsystemet stiger. Tog og metro er hovedpulsårerne, mens busserne er de livsnødvendige forbindelser, som sørger for at passagererne kan komme hurtigt og direkte til og fra metro og tog og ud i alle forgreninger. Så når Cityringen åbner i 2019, skal bussernes funktion også passes til, så der sikres størst muligt samspil og dermed bedst muligt grundlag for udvikling, vækst og beskæftigelse i hele hovedstadsområdet. Bussernes nye funktion i hovedstadsområdet er samlet i: Nyt Bynet. Nyt Bynet omfatter det strategiske net bestående af A-, C- og S-busser såvel som de lokale buslinjer. -

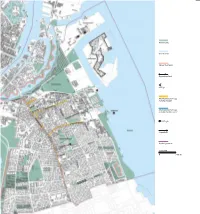

13. Sundbyøster Overordnede Rumlige Træk

Friområde Vandareal Visuel barriere Bygningsfront Udsigt Markant byrum og rumligt forløb Markant byrum og rumligt forløb vand Vartegn Sigtelinie Bydelsgrænse 1:20.000 0 500 m 13. Sundbyøster Overordnede rumlige træk. Amager har helt sin egen Strandparken er der vid udsigt over Øresund. Bydelens overordnede rumlige træk med bymassivet identitet som ø med kun få broforbindelser over havnelø- Øens hovednerve, Amagerbrogade, afgrænser bydelen mod nord opleves mest markant ved ankomsten til byde- bet til Københavns centrale dele, og øen udgør på tværs mod vest. len fra nord, hvor Christmas Møllers plads virker som en af administrative grænser en helhed. Det er også karakte- byport, understreget af at facadebygningerne mod plad- ristisk for hele øen, at den er ganske lav og flad med kun Tæt karrébebyggelse ligger i den centrale/nordlige del på sen danner en let tragtformet indgang til Amagerbrogade. svage terrænforskelle. Amagerbro som kontrast til de åbne områder i nordøst med bl.a. Kløvermarkens grønninger og Amagerværket, Ned gennem bydelen danner de fire veje Prags Boule- Bydelen Sundbyøster er den østligste af Københavns tre og til de udstrakte haveboligområder i den sydlige del af vard, Lergravsvej, Italiensvej og Greisvej karakteristiske bydele på Amager, og den er et varieret og sammensat bydelen. tværgående, grønne bånd, som leder ud til kysten. byområde med mange grønne områder. De overordnede elementer, som afgrænser bydelen Prøvestenen udgør et særligt område, og øens bebyggel- med markante landskabstræk er Christianshavns voldan- se med store benzin- og oliebeholdere opleves som en læg mod nord og Amager Strandpark mod Øresund. Fra sammenhængende front set fra Amager. Beliggenhed Bebyggelsesstruktur Vejstruktur 3. -

Metro Projects

CITYRINGEN FACT SHEET PROJECTPROJECT OVERVIEW OVERVIEW ONE OF EUROPE’S BIGGEST METRO PROJECTS Copenhagen Four hundred years after The line is to provide a Christian IV ordered the construction of Christianshavn round-the-clock service 4 inutes 72 illion to extend the fortifications ˜ to travel passengers for a potential of up to 72 entire line a year of the city, Copenhagen has overseen another mega million passengers a year. infrastructure project which Cityringen encircles the heart reshapes the urban space: of Copenhagen with two Cityringen, the new metro parallel 15.5-kilometre-long line that will help it in its tunnels. It passes under the bid to become the greenest historic centre, the so-called capital in the world. The “bridge quarters”, as well as project, commissioned by the independent municipality Metroselskabet, the public etres of Frederiksberg, which is 30 entity responsible for the located within Copenhagen’s 17 metro network, was designed below street level underground borders. The line has 17 stations and built by Salini Impregilo underground stations situated via a local entity called CMT. an average 30 metres below 8000 The project supports the street level. Driverless and seconds completely automatic trains trains’ frequency aim to achieve carbon pass every 100 seconds and as little as 80 seconds at rush neutrality by 2025 as part hour. of the CPH Climate Plan. Thanks to the new line and Driverless its connections to the existing fully automated network, residents will be able trains to move by foot, bike or public transport for 75 percent of their long trips. 40 m/h 155 average travelling The Cityringen metro speed encircles the very heart of Copenhagen with 2 parllel tunnels 3 INNOVATION AND TECHNICAL HIGHLIGHTS The underground race of the 4 TBM One of the greatest challenges of The TBMs – tunnel boring Works carried out building Cityringen was having machines - excavated 31 in ensel populate rea, to do it in kilometres under the streets near historicl buildings highly urbanised areas through different and, at times, difficult geology. -

Analysing Accessibility Effects in a Continuous Treatment Framework: the Case of Copenhagen Metro

View metadata,Downloaded citation and from similar orbit.dtu.dk papers on:at core.ac.uk Dec 20, 2017 brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research Database In Technology Analysing accessibility effects in a continuous treatment framework: the case of Copenhagen metro Pons Rotger, Gabriel Angel; Nielsen, Thomas Alexander Sick Publication date: 2013 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Pons Rotger, G. A., & Nielsen, T. A. S. (2013). Analysing accessibility effects in a continuous treatment framework: the case of Copenhagen metro. Abstract from Strategisk forskning i transport og infrastruktur, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Drivers- and Limits Analysing accessibility effects in a continuous treatment framework: the case of Copenhagen metro Gabriel P. Rotger, Thomas Sick Nielsen SFI, KORA DTU Transport This paper tests the the impact of a public transport infrastructure on commuting distances by analysing the behaviour of workers who were living in the neighbourhood of the new facility when the location of stations was decided. -

Islands Brygge Metrostations Plads 11

PLADS GUIDE AMAGER GENEREL INFORMATION Nedenfor finder du en oversigt over de fleste Alt strømforbruget vil blive opkrævet af Byliv. af pladserne/parkerne du kan låne til udendørs Skal du have adgang til vand eller tilsluttes kloak arrangementer i Københavns Kommune. på pladsen til et arrangement, så kontakt Hofor. Alle udgifter dertil afholdes af arrangøren selv. Under hver plads eller park i guiden finder du kort over pladsen, beskrivelse af pladsen, hvilke typiske KØRSEL OG PARKERING PÅ PLADSEN aktiviteter for netop den valgte plads, hvad der er Der må ikke køres eller parkeres på pladsen uden særlig af fast udstyr på pladsen og om der er specielle tilladelse fra kommunen. Der må ikke opstilles eller henstillinger. køres med tunge køretøjer (over 3500 kg.) uden der er søgt og givet dispensation. Er der andre krav vil fremgå Du kan finde kortene her: http://kbhkort.kk.dk under selve pladsen. (klik Erhverv, aktiviteter, arrangementer.) MUSIK OG OPTRÆDEN FÆLLES FOR BRUG AF ARRANGEMENTSPLADSER Det er tilladt enkeltpersoner og grupper på højst 3 OG PARKER: personer at optræde med levende musik (akustisk Har du planer om at ville afholde et arrangement på musik uden forstærkeranlæg) på pladsen én time pladsen, er det vigtigt at du søger om tilladelse i god om dagen i følgende tidsrum: tid. Behandlingstiden for ansøgninger er normalt 14 dage. Tilladelsen søger du gennem Byliv og du kan Mandag – søndag indtil kl. 22.00 gøre det via arrangementshjemmesiden: www.kk.dk/ arrange menter. Der skal søges om tilladelse til musik og optræden ud over dette omfang. Der vil under hver plads stå, hvis Som arrangør skal du være opmærksom på at dit der er særlige forhold. -

Til Andreas Keil, MB E-Mail

KØBENHAVNS KOMMUNE Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningen Direktionen Til 30. januar 2019 Andreas Keil, MB Sagsnr. E-mail: [email protected] 2019-0000199 Dokumentnr. 2019-0000199-14 Kære Andreas Keil Tak for din henvendelse af d. 16. januar 2019, hvor du har stillet spørgsmål til Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningen vedr. virk- somhedspraktikker. De spørgsmål, du har stillet, er oplistet nedenfor med forvaltningens svar angivet efter hvert spørgsmål. Vi har notatet igennem behandlet dine spørgsmål ud fra en forudsæt- ning om, at du spørger til alle virksomhedspraktikker. Vi har således ikke opdelt opgørelserne i målgrupper (jobparate borgere, aktivitetspa- rate borgere mv.), men i stedet udarbejdet opgørelser for alle borgere samlet set. Virksomhedspraktikker gives ofte med forskelligt formål, da borgerne i de forskellige målgrupper har forskellige behov. Spørgsmål 1 Hvilke virksomheder ansætter ledige i ordinære job efter virksomheds- praktik, og hvilke virksomheder ansætter ikke virksomhedspraktikan- ter efter endt praktik? Der ønskes en oversigt. Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningens svar Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningen kan ikke se, hvilke virk- somheder der ansætter ledige efter virksomhedspraktik. Det vil kræve et manuelt opslag i e-indkomst i hver enkelt borgersag. Forvaltningen har i stedet udarbejdet en oversigt, der viser de virk- somheder, der har haft borger(e) i virksomhedspraktik, som er blevet ordinært ansat i samme branche i 2. måned efter endt virksomheds- praktik. Oversigten er opgjort for alle borgere samlet og altså ikke op- delt på målgrupper. Oversigten er afgrænset til virksomhedspraktikker i perioden juli 2017-juni 2018. Oversigten siger således ikke noget om, hvorvidt borgeren er blevet ansat i et ordinært job i samme virk- somhed, som han/hun var i virksomhedspraktik i. -

Trains & Stations Ørestad South Cruise Ships North Zealand

Svejager- Henningsens Bjergtoften NielsAndersens Vej Højgårds Allé Helsebakken Gersonsvej vej Allé På Højden Eggersvej Hellerupvej Jomsborgvej Fruevej Rødstensvej Stenagervej So Sønderengen fievej Grøns Mausoleum Ellemosevej j Svejgårdsvej Aftenbakken entorpsve årdsvej Vandtårnsvej Vilh. Niels FinsensAllé Dalstrøget Dalsv Kirkehøj Amm Onsg Forsvarsvej Batterivej Bergsøe Onsgårds Ø Tværvej stmarken Allé inget Byværnsvej j Aakjærs Allé é Hjemmevej Rygårds- Nordahl Griegs Vej Ravnekærsvej Thulevej C. V. E. Knuths Vej vænget Sydfrontve Erik Bøghs Allé Hellerup sens Vej Hellerupvej Søborg Park Allé Lykkesborg Allé ans Jen Lystbådehavn Ved Kagså H Strandparksvej Røntoftevej Stor j Frödings All Rake dyssen rove tsvej teb Munkegårdsvej Lyngbyvej Præs Hf. Mosehøj Stendyssevej Sydmarken Hyrdevej Hellerup Heller Dysse- en Hulkærsv Dagvej upgårdsv rd Marienborg Allé ej Dyssegårdsvej Lyngbyvej RygårdsAllé station ej Fr Gladsaxe Ringvej Sydmarken Knud RasmussensVej Dæmringsvej ederikkev stien dgå Wergelands Allé ej Langdyssen Søborg Ho Kodans- Mørkhøj Bygade Gladsaxe Møllevej Run ers Vej Vangedevej Skt. Ped Hillerødmotorvejen vej Kagsåvej Dyssebakken Dyssegårdsve Ruthsvej vedg j Marievej Hellekisten emosevej Almindingen Vand Gyng Gustav Runebergs Allé ade revej Esthersvej Knud Højgaards Vej Wieds Vej Callisensvej Dynamovej Transformervej Munkely Ewaldsbakken Bernstorffsvej Isbanevej vej Runddyssen Mindevej Helsingørmotorvejen Barkæret Carolinevej Tellers- Plantevej Nordkro Selma Lagerløfs Allé Grants Allé Morgenvej Hvilevej Rebekkavej g Vespervej Ardfuren