Droughts, Distress and a Conditional Cash Transfer Program to Mitigate the Impact of Drought in Bihar, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ground Water Year Book, Bihar (2015 - 2016)

का셍ााल셍 उप셍ोग हेतू For Official Use GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD जल ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पूर्वी क्षेत्र, पटना सितंबर 2016 MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA September 2016 ` GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES जल CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पर्वू ी क्षेत्र, पटना MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA सितंबर 2016 September 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Annexures ii List of Contributors iii Abstract iv 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 2. HYDROGEOLOGY..........................................................................................................1 3. GROUND WATER SCENARIO......................................................................................4 3.1 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL........................................................................................8 3.1.1 MAY 2015.....................................................................................................................8 3.1.2 AUGUST 2015..............................................................................................................10 3.1.3 NOVEMBER 2015........................................................................................................12 3.1.4 JANUARY 2016...........................................................................................................14 -

41629-013: Bihar State Highways II Project

Social Monitoring Report Project Number: 41629-013 / 44425-013 September 2019 Period: January 2018 – June 2018 IND: Bihar State Highway II Project SH – 78 Submitted by Bihar State Road Development Corporation Limited, Patna This social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Bihar State Highway Project Phase – II CONTRACT PACKAGE NO.1& 2 (SH-78) (Bihta – Sarmera) Monitoring and Implementation of Resettlement Plan (RP) Semi Annual Report January 2018 - June 2018 Submitted By Egis International S.A in JV with Egis India Consulting Engineers Pvt. Ltd. Plot No.66, Sec.32 Gurgaon-122001 CONTENTS Abbreviation ................................................................................................................................................... 2 GLOSSARY ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 4 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .......................................................................................................................... -

Womens' Empowerment

Directory of Voluntary Organisations Women’s Empowerment 2010 Documentation Centre for Women and Children (DCWC) National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 5, Siri Institutional Area, Hauz Khas, New Delhi – 110016 Number of Copies: 100 Copyright: National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development, 2010 Project Team Project In-charge : Mrs. Meenakshi Sood Project Team : Ms. Renu Banker Ms. Alpana Kumari Computer Assistance : Mrs. Sandeepa Jain Mr. Abhishek Tiwari Acknowledgements : Ministry of Women and Child Development Planning Commission Voluntary Organisations Ministry of Rural Development Ministry of Panchayati Raj Ministry of Tribal Affairs Ministry of Urban Development DISCLAIMER All efforts have been made to verify and collate information about organisations included in the Directory. Information has been collected from various sources, namely directories, newsletters, Internet, proforma filled in by organisations, telephonic verification, letter heads, etc. However, NIPCCD does not take any responsibility for any error that may inadvertently have crept in. The address of offices of organisations, telephone numbers, e-mail IDs, activities, etc. change from time to time, hence NIPCCD may not be held liable for any incorrect information included in the Directory. Foreword Voluntary organisations play a very important role in society. They take up activities in the area of their expertise and provide support to the community in whose welfare they have interest. Social development has been ranked high on the priority list of Government programmes since Independence, and voluntary organisations have been equal partners in accelerating the pace of development. Being in close proximity to the community, voluntary organisations have done pioneering work in many areas, rendered productive services, highlighted several social problems, undertaken advocacy, and lobbied for the rights of the underprivileged. -

Provisional Population Totals, Series-11, Bihar

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES- 11 BIHAR PAPER 1 OF 2001 PROVISIONAL POPULATION TOTALS SUDHIR KUMAR RAKESH Director of Census Operations, Bihar Lord Buddha Dedicated to the people of Bihar and enumerators - the data producers. For the benefit of policy makers and research workers - the data consumers. CONTENTS SL. NO. PARTICULARS PAGE NO. 1. Foreword v 2 List of Officers! Officials involved in preparation of Provisional Population Totals vii 3 Figures at a Glance ix 4 State Highlights x 5 Map showing Administrative Division of India Highlighting State xi 6 Map showing Administrative Division of State, 2001 Census xiii 7 Introduction 1 8 Analysis of Results 7· 9 Provisional Population Tables 25 10 Maps 31 11 Diagrams and Charts 39 12 Organisational Chart of Census Hierarchy 49 13 Specimen Copy of Houselist Schedule 51 - 14 Specimen Copy of Household Schedule 53 15 Pictorial 55 FOREWORD After the successful completion of Census of India 2001, it gives me great pleasure to present these provisional population totals for the state of Bihar. This paper gives some basic characteristics of the population of Bihar as on 1st March, 2001 (00.00 hrs.) as recorded during the population enumeration related with the Census of India 2001. These figures are only provisional ones, compiled on the basis of the abstracts of population data prepared by the enumerators. These provisional population figures are being published with the intention of meeting the immediate need of the Government, various organisations, researchers and the general public. It would help provide them the basic population figures as quickly as possible after the population enumeration work has been completed. -

Initial Environmental Examination: India, Bihar Power System

Environmental Assessment Report Final Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 41626 August 2010 IND: Bihar Power System Improvement Project The Final environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Government of Bihar Bihar State Electricity Board BIHAR POWER SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FINAL REPORT INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION DISTRIBUTION COMPONENT AUGUST 2010 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GOVERNMENT OF BIHAR COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of government of Bihar & Asian Development Bank. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of either Government of Bihar or Asian Development Bank constitutes an infringement of copyright. Bihar Power System Improvement Project FINAL REPORT INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION BIHAR POWER SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT PROJECT DISTRIBUTION COMPONENT Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vi A. Assessment of Legal Framework and Policy vi B. Anticipated Environmental Impacts vii C. Environmental Assessment for the Project x D. Environment Management Plan xi E. Institutional Arrangements and Responsibilities xiv F. Monitoring and Reporting xiv G. Public Consultation and Information Disclosure xv H. Grievance Redress Mechanism xv 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Overview 1 1.2 Project Goal and Objective 2 1.3 Purpose of IEE Study 2 1.4 Scope of the IEE 2 1.5 Report Structure 2 2 POLICY -

Agricultural Development in Bihar

t: PAL AGRICUL TURAL DEVELOPMENT IN BIHAR ,... I I ,I ,'V'-I Challenges Fig. 2.1: Trends in Productivity of Foodgrains in Bihar and India & 2~.-~------------------~------- Opportunities 000 - .t:. ~~----~~------------~~ x -:2 >- 000r----------------------------- By 500 T. Haque :I Q Council for Social Development New Delhi • • • [~ ..- ~ AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT IN BIHAR CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES By T. HAQUE About the author Dr. T. Haque is a well known Agricultural Economist. He is currently Director, Council for Social Development, New Delhi, Senior Adviser, LANDESA (Rural Development Institute), New Delhi, and Vice-Chairman, Council for Development of Bihar and Jharkhand, New Delhi. Earlier he served as Chairman, Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, Govt. of India, ICAR National Fellow at the National Centre for Agricultural Economics and Policy Research, New Delhi and Director, Centre for Agrarian Studies, NIRD, Hyderabad and Senior Scientist at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi. His email [email protected] Acknowledgements The author is grateful to Dr. P.K. Joshi, Director, IFPRI in South Asia, New Delhi for his help and support in preparing an earlier research report, based on which this Policy paper has been produced. The help received from Gaurav Tripathi of IFPRI in South Asia and Gitesh Sinha of CSD, New Delhi in compilation of data is also thankfully acknowledged. T. Haque CONTENT Page No. 1.0 Overview 1 2.0 Agricultural Growth and Variability 6 2.1 Crop Production 6 2.2 Horticulture 12 -

Annual Report Nalanda University

Annual Report Nalanda University 2010-2011 & 2011-2012 NEW DELHI OFFICE 2st Floor, Council for Social Development Sangha Rachna, 53, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi – 110 003 Tel. +91-11 24618352, +91-11 26172328 Fax: +91-11 24618351 RAJGIR OFFICE Rajgir, District Nalanda, Pin: 803 115 Bihar, India www.nalandauniv.edu.in Annual Report 2010-2011 & 2011-2012 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Nalanda University: Past & Present 2 Governing Board 10 Vision Statement 13 Our Logo and Identity 15 Chairperson’s Message 17 Vice Chancellor’s Report 22 Academic Planning 39 Financial Management 45 Campus 47 Officers and Employees 50 NEW DELHI OFFICE 2st Floor, Council for Social Development Sangha Rachna, 53, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi – 110 003 Tel. +91-11 24618352, +91-11 26172328 Fax: +91-11 24618351 RAJGIR OFFICE Rajgir, District Nalanda, Pin: 803 115 Bihar, India www.nalandauniv.edu.in Foreword We are pleased to present the first Annual Report of Nalanda University. The report covers the period November 2010 to March 2012, i.e. part of the financial year 2010-2011 and the full financial year 2011-2012. The report outlines in detail the developments at Nalanda University in addition to providing a vision statement. Further, it also provides a brief historical background of ancient Nalanda University and its revival as a modern University in November 2010. The Annual Report comprises a message from the Chairperson and reports from the Vice Chancellor, the Officer on Special Duty (OSD) University Development and Academic Affairs and Officer on Special Duty (OSD) Finance on various aspects of the development of the University. -

NALANDA Preface

DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN 2010-11 NRHM N A L A N D A DISTRICT HEALTH SOCIETY, NALANDA Preface National Rural Health Mission offers unprecedented opportunity to improve the health of the people of Nalanda District. The Public Health System of Nalanda District, through its more than 650ANMs, 2000 of ASHAs, 2000 of Aaganwadi Workers and hundred of doctors reaches out to the people living in more than 1500 villages. The Public Health infrastructure, particularly PHCs/CHCs and other Government hospitals ought to be the institutions where people can put their trust for good and affordable quality health services as per needs. Though the role of Public Health system is primarily important, NRHM heralds a new beginning where the health of the people will be placed in their own hands and government will play a role of facilitator providing all round support and ensuring access to health services. The PIP has been prepared through consultation with block and village level functionaries. The plans have been prepared on the needs identified and has addressed lots of critical issues to implement the programme. The plan is aimed at improving the access to comprehensive quality health care by improving the public health infrastructure to desired standards and placing the health of the people in their hands. Government will play the role of a facilitator and undertake new initiatives. As planned here the capacity to manage the programme in the district is going to be significantly strengthened. The Programme Management Support Units at the block level, HMIS and the support systems shall also be strengthened. -

Technical Assistance Consultant's Report

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 43166-062 May 2013 India: Advanced Project Preparedness for Poverty Reduction - Institutional Development for a Value Chain Approach to Agribusiness in Bihar (Financed by the Government of the United Kingdom) Prepared by IL&FS Cluster Development Initiative Ltd. In collaboration with Agrifood Consulting International For Bihar Department of Agriculture This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. Advanced Project Preparedness for Poverty Reduction - Institutional Development for a Value Chain Approach to Agribusiness in Bihar (Contract No. : 100146-S41802) Final Report Submitted to: Asian Development Bank Prepared by: In collaboration with: Agrifood Consulting International 1 Knowledge Summary ....................................................................................... 10 1. Introduction .................................................................................................. 13 1.1 Background - Technical Assistance Programme ................................. 13 1.2 Approach of TA Programme ................................................................. 14 1.2.1 Field Survey .................................................................................... 14 1.2.2 Stakeholders’ Consultations ......................................................... 15 1.2.3 Capacity Building Initiatives ....................................................... -

Fact Sheets Fact Sheets

DistrictDistrict HIV/AIDSHIV/AIDS EpidemiologicalEpidemiological PrProfilesofiles developeddeveloped thrthroughough DataData TTriangulationriangulation FFACTACT SHEETSSHEETS BiharBihar National AIDS Control Organisation India’s voice against AIDS Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India 6th & 9th Floors, Chandralok Building, 36, Janpath, New Delhi - 110001 www.naco.gov.in VERSION 1.0 GOI/NACO/SIM/DEP/011214 Published with support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Cooperative Agreement No. 3U2GPS001955 implemented by FHI 360 District HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Profiles developed through Data Triangulation FACT SHEETS Bihar National AIDS Control Organisation India’s voice against AIDS Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India 6th & 9th Floors, Chandralok Building, 36, Janpath, New Delhi - 110001 www.naco.gov.in December 2014 Dr. Ashok Kumar, M.D. F.I.S.C.D & F.I.P.H.A Dy. Director General Tele : 91-11-23731956 Fax : 91-11-23731746 E-mail : [email protected] FOREWORD The national response to HIV/AIDS in India over the last decade has yielded encouraging outcomes in terms of prevention and control of HIV. However, in recent years, while declining HIV trends are evident at the national level as well as in most of the States, some low prevalence and vulnerable States have shown rising trends, warranting focused prevention efforts in specific areas. The National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) is strongly evidence-based and evidence-driven. Based on evidence from ‘Triangulation of Data’ from multiple sources and giving due weightage to vulnerability, the organizational structure of NACP has been decentralized to identified districts for priority attention. The programme has been successful in creating a robust database on HIV/AIDS through the HIV Sentinel Surveillance system, monthly programme reporting data and various research studies. -

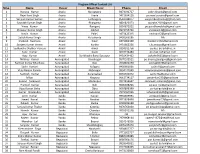

Mobile No. and E-Mail Address of Programme

Program Officer Contact List Slno. Name Descr Block Descr Phone Email 1 Hansraj Kumar Araria Narpatganj 9473191727 [email protected] 2 Rajni Kant Singh Araria Araria 9471634128 [email protected] 3 Sanjeev Kumar Suman Araria Forbesganj 8544188977 [email protected] 4 Saurabh Kumar Singh Araria Bhargama 9801823973 [email protected] 5 Vinay Kumar Araria Raniganj 9304872022 [email protected] 6 Shrawan Kumar Singh Araria Jokihat 9973755740 [email protected] 7 Navin Kumar Araria Palasi 9473423315 [email protected] 8 Satish Kumar Singh Araria Kursakanta 9430566186 NA 9 Shailesh Swaroop Arwal Kaler 9471002340 [email protected] 10 Sanjeev Kumar Verma Arwal Kurtha 9431863336 [email protected] 11 Sudhanshu Shekhar Pandey Arwal Arwal 9334912758 [email protected] 12 Sunil Kumar Arwal Karpi 9097774484 [email protected] 13 Ajay Kumar Arwal Sonbhadra Bansi Suryapur 9431434402 [email protected] 14 Nirbhay Kumar Aurangabad Daudnagar 9570103521 [email protected] 15 Santosh Kumar Bhardwaj Aurangabad Deo 7004802150 [email protected] 16 Sashi Kumari Aurangabad Rafiganj 9430905936 [email protected] 17 Vijay Ranjan Parmar Aurangabad Nabinagar 9934121049 [email protected] 18 Santosh Kumar Aurangabad Aurangabad 8092481072 [email protected] 19 Milan Aurangabad Haspura 9661734117 [email protected] 20 Kumari Saraswati Aurangabad Madanpur 9973454647 [email protected] 21 Pramod Kumar Aurangabad Goh 9006638226 [email protected] 22 Vijay Kumar Sinha Aurangabad Obra 9097893399 [email protected] -

District Profile Nalanda Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE NALANDA INTRODUCTION Nalanda district is a part of the Patna division Nalanda is famous all over the world for the ancient International Monastic University established in 5th century BC, which taught Vedas, Logic, Grammar, Medicine, Meta-Physics, Prose Composition and Rhetoric Nalanda district is popularly known as Biharsharif. The rivers Phalgu, and Mohane flows through the district of Nalanda. Agriculture is the main source of occupation Tourism plays an important role in the economy of Nalanda. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The ancient university town of Bihar, goes back to the days of Buddha and Mahavira in the Sixth Century B.C. The town was home to Nalanda Mahavihara, a monastic university of international repute Both Buddha and Mahavira often stayed at Nalanda during the rainy season. Buddhist scriptures reveal that they once stayed at Nalanda at the same time, but there is no record of them meeting one another. It was a flourishing hub where the philosopher and alchemist, Nagarjuna, studied and taught in the Second Century A.D. However, excavations have not revealed anything to suggest that the site was occupied before the Gupta period (Fifth Century A.D.), the earliest finds being a copper plate of Samudragupta and a coin of Kumaragupta (414-455 A.D.). Fa-Hien who visited in the Fifth Century A.D. makes no mention of the massive monastic establishments at Nalanda. But Hiuen Tsang who came in A.D 637 during Harsha's reign (606-647 A.D.) refers to the great monastery that Harsha endowed with liberal grants. ADMINISTRATIVE Biharsharif town is the district headquarters.