Making a Public Difference in the Ministry of Word and Witness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism Heith

Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism Heith-Stade, David Published in: Theoforum 2010 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Heith-Stade, D. (2010). Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism. Theoforum, 41(3), 373- 385. https://www.academia.edu/1125117/Eastern_Orthodox_Ecclesiologies_in_the_Era_of_Confessionalism Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Theoþrum, 4l (2010), p. 37 3-385 Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism "[I believeJ in one, holy, catholic and apostolic church." Creed -Nicaeno-Constantinopolitan DAVID HEITH-STADE Lund University, Sweden The Eastern Orthodox Church was a self-evident phenomenon in Byzantine society. -

Catholicism Episode 6

OUTLINE: CATHOLICISM EPISODE 6 I. The Mystery of the Church A. Can you define “Church” in a single sentence? B. The Church is not a human invention; in Christ, “like a sacrament” C. The Church is a Body, a living organism 1. “I am the vine and you are the branches” (Jn. 15) 2. The Mystical Body of Christ (Mystici Corporis Christi, by Pius XII) 3. Jesus to Saul: “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:3-4) 4. Joan of Arc: The Church and Christ are “one thing” II. Ekklesia A. God created the world for communion with him (CCC, par. 760) B. Sin scatters; God gathers 1. God calls man into the unity of his family and household (CCC, par. 1) 2. God calls man out of the world C. The Church takes Christ’s life to the nations 1. Proclamation and evangelization (Lumen Gentium, 33) 2. Renewal of the temporal order (Apostolicam Actuositatem, 13) III. Four Marks of the Church A. One 1. The Church is one because God is One 2. The Church works to unite the world in God 3. The Church works to heal divisions (ecumenism) B. Holy 1. The Church is holy because her Head, Christ, is holy 2. The Church contains sinners, but is herself holy 3. The Church is made holy by God’s grace C. Catholic 1. Kata holos = “according to the whole” 2. The Church is the new Israel, universal 3. The Church transcends cultures, languages, nationalism Catholicism 1 D. Apostolic 1. From the lives, witness, and teachings of the apostles LESSON 6: THE MYSTICAL UNION OF CHRIST 2. -

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Grade 8 Focus: Church History

Religion Grade 8 Focus: Church History Topic: Prayer Grade 8 Learning Outcomes Teaching/Learning Strategies Prayer The students will be able to: • Recite by heart the prayers listed in the DFR Religion Curriculum Prayer List. • Explain how the Apostle’s Creed and Nicene Creed summarize our Catholic beliefs. (see Doctrine below.) • Recognize that different types of images can be aids for prayer. (i.e., icons, statues, stained glass, art & architecture) • Recognize the diversity of prayer forms within the Eastern and Western Rites of the Church. • Compose prayers of praise/adoration, thanksgiving, petition/supplication and contrition/sorrow. • Describe why prayer, the study of the Word of God and the Church’s teachings are essential in our faith lives and the life of our Church. • Recognize that liturgical prayer is the official prayer of the Church. • Explain that liturgical prayer is the Mass, as well as the celebration of the sacraments and the Liturgy of the Hours. Values/Attitudes Resources Assessment Religion Grade 8 Focus: Church History Prayer Grade 8 Learning Outcomes Teaching/Learning Strategies • Explain that the Liturgy of the Hours is prayed by all priests and many religious and laypersons throughout the world. • Explain the role and benefits of private devotion. • Discuss the history of the Rosary. • Explain how the Rosary helps the Church to “contemplate the face of Christ at the school of Mary” • Become familiar with a variety of devotional practices, especially as listed in the DFR Supplementary Prayer List • Personally engage themselves in prayer and devotions, chosen from the richness of our Catholic Tradition. Values/Attitudes Resources Assessment Religion Grade 8 Focus: Church History Topic: Sacraments Grade 8 Learning Outcomes Teaching/Learning Strategies Sacraments The students will be able to: • Describe how the sacraments of Service build the community of the Church. -

Week 1 Catholic Quiz

So – You Think You Know Your Catholic Faith? Catholic Quiz 1. The Catholic Church teaches that non-Catholics will not go to Heaven. a. True b. False 2. What is the term for the change of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ during the Mass? a. Sacramentalization b. Consubstantiation c. Transubstantiation d. Transformation 3. The feast of the Immaculate Conception refers to whose conception? a. The Angels b. Jesus c. The Virgin Mary d. Eve 4. Where do souls who are still in need of purification from minor sins go after death? a. Limbo b. Heaven c. Purgatory d. Hell 5. Which of these heresies maintained that Christ was not truly God? a. Sabellianism b. Arianism c. Gnosticism d. Protestantism 6. The Council of Ephesus (AD 431) gave Mary the title of Theotokos, which means: a. Immaculate Virgin b. Mother of the Church c. Queen of Heaven d. God-Bearer 7. What does “Catholic” mean? a. Revealed b. Universal c. Ancient d. Apostolic 8. According to the Church, contraception is allowed in a marriage but not for singles. a. True b. False 9. Married men are allowed to be ordained as priests in some Rites of the Catholic Church. a. True b. False 10. What is the term for the belief that God created the universe from nothing? a. Sola Scriptura b. Nihil Obstat c ) Sola Fide d. Ex Nihilo 11. Infallibility means that the Pope cannot make mistakes. a. True b. False 12. Purgatory is a second chance at salvation for those who did not die in a state of grace. -

POCKET CHURCH HISTORY for ORTHODOX CHRISTIANS

A POCKET CHURCH HISTORY for ORTHODOX CHRISTIANS Fr. Aidan Keller © 1994-2002 ST. HILARION PRESS ISBN 0-923864-08-3 Fourth Printing, Revised—2002 KABANTSCHUK PRINTING r r ^ ^ IC XC NI KA .. AD . AM rr In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, amen. GOD INCARNATES; THE CHURCH FOUNDED OME 2,000 years ago, our Lord Jesus Christ directly intervened in human history. Although He S is God (together with the Father and the Holy Spirit), He became a man—or, as we often put it, He became incarnate —enfleshed. Mankind, at its very beginning in Adam and Eve, had fallen away from Divine life by embracing sin, and had fallen under the power of death. But the Lord Jesus, by His incarnation, death upon the Cross, and subsequent resurrection from death on the third day, destroyed the power death had over men. By His teaching and His whole saving work, Christ reconciled to God a humanity that had grown distant from God1 and had become ensnared in sins.2 He abolished the authority the Devil had acquired over men3 and He renewed and re-created both mankind and His whole universe.4 Bridging the abyss separating man and God, by means of the union of man and God in His own Person, Christ our Saviour opened the way to eternal, joyful life after death for all who would accept it.5 Not all the people of Judea, the Hebrews, God’s chosen people (Deut 7:6; Is 44:1), were ready to hear this news, and so our Lord spoke to them mostly in parables and figures. -

Prek – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018

PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018 Page 1 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 Page 2 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 TABLEU OF CONTENTS PreKU – 8 Course of Study U Introduction .......................................................................................................................7 PreK – 8 Content Structure: Scripture and Pillars of Catechism ..............................9 PreK – 8 Subjects by Grade Chart ...............................................................................11 Grade Pre-K ....................................................................................................................13 Grade K ............................................................................................................................20 Grade 1 ............................................................................................................................29 Grade 2 ............................................................................................................................43 Grade 3 ............................................................................................................................58 Grade 4 ............................................................................................................................72 Grade 5 ............................................................................................................................85 -

Anglican Orthodox

The Dublin Agreed Statement 1984 Contents Abbreviations Preface by the Co-Chairmen Introduction: Anglican-Orthodox Dialogue 1976-1984 The Agreed Statement Method and Approach I The Mystery of the Church Approaches to the Mystery The Marks of the Church Communion and Intercommunion Wider Leadership within the Church Witness, Evangelism, and Service II Faith in the Trinity, Prayer and Holiness Participation in the Grace of the Holy Trinity Prayer Holiness The Filioque III Worship and Tradition Paradosis - Tradition Worship and the Maintenance of the Faith The Communion of Saints and the Departed Icons Epilogue Appendices 1 The Moscow Agreed Statement 1976 2 The Athens Report 1978 3 List of Participants 4 List of Papers by Members of the Commission Abbreviations ACC Anglican Consultative Council AOJDD Anglican-Orthodox Joint Doctrinal Discussions ARC1C Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission ECNL Eastern Churches Newsletter PC Migne, J.-P., Patrologia Graeca PL Migne, J.-P., Patrologia Latina Preface It was Archbishop Basil of Brussels, one of the most revered Orthodox members of the Anglican-Orthodox Joint Doctrinal Commission, who remarked that the aim of our Dialogue is that we may eventually be visibly united in one Church. We offer this Report in the conviction that although this goal may presently seem to be far from being achieved, it is nevertheless one towards which God the Holy Spirit is insistently beckoning us. Those who have served on the Commission at every stage since its inception in 1966, and since our own Co-Chairmanship began in 1980, have been aware that this is the case, although we may sometimes have been tempted to think otherwise. -

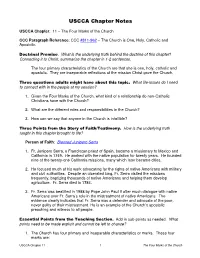

USCCA Chapter Notes

USCCA Chapter Notes USCCA Chapter : 11 – The Four Marks of the Church CCC Paragraph Reference : CCC #811-962 – The Church is One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic. Doctrinal Premise . What is the underlying truth behind the doctrine of this chapter ? Connecting it to Christ, summarize the chapter in 1-2 sentences. The four primary characteristics of the Church are that she is one, holy, catholic and apostolic. They are inseparable reflections of the mission Christ gave the Church. Three questions adults might have about this topic. What life-issues do I need to connect with in the people at my session? 1. Given the Four Marks of the Church, what kind of a relationship do non-Catholic Christians have with the Church? 2. What are the different roles and responsibilities in the Church? 3. How can we say that anyone in the Church is infallible? Three Points from the Story of Faith/Testimony. How is the underlying truth taught in this chapter brought to life? Person of Faith : Blessed Junipero Serra 1. Fr. Junipero Serra, a Franciscan priest of Spain, became a missionary to Mexico and California in 1749. He worked with the native population for twenty years. He founded nine of the twenty-one California missions, many which later became cities. 2. He focused much of his work advocating for the rights of native Americans with military and civil authorities. Despite an ulcerated lung, Fr. Serra visited the missions frequently, baptizing thousands of native Americans and helping them develop agriculture. Fr. Serra died in 1784. 3. Fr. Serra was beatified in 1988 by Pope John Paul II after much dialogue with native Americans over Fr. -

Assessing the Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa in the Light of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church

From Vision to Structure From vision to structure: Assessing the Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa in the light of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church. Daniël Nicolaas Andrew A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor theologia in the faculty of arts, University of the Western Cape. Supervisor: Professor D.J. Smit November 2005 i From Vision to Structure KEYWORDS 1. Vision 2. Structure 3. One 4. Holy 5. Catholic 6. Apostolic 7. Experience 8. Tradition 9. Models 10. Dialogical ii From Vision to Structure ABSTRACT The intention of the AFMSA to revision its policies, processes and structures is the motivation for this study. The relationship between the vision and essential nature of the church and the structure or form given to it is central to all the chapters. The first chapter gives an analysis of the origins of the Pentecostal Movement and the AFMSA in order to reveal their original vision of the church and the way in which this vision became structured in their history. After a section on the importance of a clear vision and strategic structures for organizations today, the biblical metaphors that served as a foundation for the early Christians’ vision of the church are discussed. Our Christian predecessors’ envisioning and structuring of the church in each period of history are analyzed. This gives an idea of the need for reform and the challenges involved in this process, which are still faced by later generations. The historical survey reveals the development of the marks and the vision of the early Christians to represent the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church. -

World Religions and the History of Christianity: Roman Catholicism

World Religions and the History of Christianity: Roman Catholicism 97 World Religions and the History of Christianity: Roman Catholicism QUESTION ANSWER •When did the ROMAN •The Church IN ROME did not Church [Geographically] become the Roman Catholic become the ROMAN Church until . CATHOLIC Church [politically]? ANSWER DARK AGES 1.The Fall of the Roman Empire 2.The circumstances of the DARK AGES. 3.The Splitting of the Church West/East. DARK AGES THE RISE… •In general, the Middle Ages are According to the ancient philosopher defined by . Aristotle, “ Nature abhors a vacuum .” 1. A lack of central government, Aristotle based his conclusion on the 2. Decline of trade, observation that nature requires 3. Population shift to rural areas, every space to be filled with 4. Decrease in learning, and something, even if that something is 5. A rise in the power of the Roman Catholic colorless, odorless air. church. http://odb.org/2011/01/21/nature-abhors-a-vacuum/ 98 World Religions and the History of Christianity: Roman Catholicism THE RISE CAUTION •The Church in Rome filled the •What ROMAN CATHOLICISM vacuum left by the fall of the is today is not what it was Roman Empire. during the Middle Ages or after the Reformation. 99 World Religions and the History of Christianity: Roman Catholicism •"Pentarchy " is a model •In the model, the Christian historically championed in church is governed by the Eastern Christianity as a heads (Patriarchs) of the five model of church relations major episcopal sees of the and administration. Roman Empire: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. -

Marks of the Church

Marks of the Church VIDEO LINK http://youtu.be/lhxxaAJ7_nY GOAL SUMMARY The goal of this session is for young people to come to a better understanding of what we mean when, on Sundays at Mass, when we profess to believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. VIDEO SUMMARY In this video, Bishop Don Hyling explains the four marks of the Church. The Church is one, united in faith and Baptism. The Church is holy, not because of us, but because God is holy and shares His life with us. The Church is catholic or universal because her embrace extend to the whole world. The Church is based on the witness of the Apostles and this calls us to mission. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Before seeing this video was there a mark of the Church that you did not understand? 2. The is made up of sinners and fallen human beings. How can we say she is “holy?” 3. Why are the four marks of the Church the “foundation” of the Catholic Church? 4. The same apostles who were friends with Jesus were the first leaders of the Catholic Church. Why is this significant? 5. Hundreds of martyrs have died for their belief in Jesus Christ and His Church. Often, when encouraged by their executioners to renounce their faith, they recited the words of the Creed. How does that impact your conviction in your own profession of faith? SEND Let’s close with everyone standing and together reciting the Nicene Creed: I believe in one God, the Father almighty, He ascended into heaven maker of heaven and earth, and is seated at the right hand of the Father.