Economic and Social Structures That May Explain the Recent Conflicts In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal

FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL NEPAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH COUNCIL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT NEPAL AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY RESEARCH SURVEY COUNCIL ON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM FOR AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY AND RURAL SURVEY DEVELOPMENT IN NEPALON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM - FOODFOR AGRICULTURE PRODUCTION ANDAND AGRICULTURERURAL DEVELOPMENT IN TERAI - IN NEPAL - FOOD PRODUCTION AND AGRICULTURE IN TERAI - FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT OCTOBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY OCTOBER(JICA) 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONALNIPPON KOEI COOPERATION CO., LTD. AGENCY VISION AND SPIRIT(JICA) FOR OVERSEAS COOPERATION (VSOC) CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. C.D.C. INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION VISION AND SPIRIT FOR OVERSEAS COOPERATION (VSOC) CO., LTD. 4R C.D.C. INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION JR 13 - 031 FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL NEPAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH COUNCIL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT NEPAL AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY RESEARCH SURVEY COUNCIL ON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM FOR AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY AND RURAL SURVEY DEVELOPMENT IN NEPALON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM - FOODFOR AGRICULTURE PRODUCTION ANDAND AGRICULTURERURAL DEVELOPMENT IN TERAI - IN NEPAL - FOOD PRODUCTION AND AGRICULTURE IN TERAI - FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT OCTOBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL -

S3 Moon Article

Nepalese Journal of Biosciences 2: 154-155 (2012) Brief Communication Comparison of populations of Melanagromyza sojae and Liriomyza sativae associated with Mung bean Vigna radiata (Linn.) Wilczek grown in Biratnagar, eastern Nepal Moon Thapa Department of Biology, Birat Campus, Biratnagar, Nepal E-mail: [email protected] Key words : Leaf miners, Diptera, Agromyzidae, legume host, Nepal Agromyzidae are popularly known as leaf miners. The larvae of these flies may form external stem mines, bore internally in stem of herbaceous plants or in the cambium of trees or feed on roots or flower heads. Approximately, there are 2750 described species with many species awaiting formal description. Research was carried out at various times to rear these flies at various places of Eastern Nepal. Those studies showed that major or key pest which causes damage in the absence of effective control measure is stem fly Melanagromyza sojae (Zehntner). Thapa (1997, 2000) has reported 5 species from this host plant. These species were Chromatomyia horticola (Goureau), Liriomyza sativa Blanchard, Ophiomya centrosematis (de Meijere), Melanagromyza sojae (Zehntner), Melanagromyza hibisci Spencer from Biratnagar, eastern Nepal. Thapa (1997) again reported 8 species of economically important agromyzid flies from Eastern terai region, Biratnagar Nepal and discussed their range of host plants. Further, Thapa (2000) reared and described 13 species of agromyzid flies belonging to 5 genera by male genitalia preparation and surveyed and determined 100 species of host plants belonging to 81 genera and 23 families from Eastern Nepal. Poudyal (2003) has reported 4 species of agromyzid flies. Mung bean Vingna radiate (L.) Wilczek var. K851 was at three locations A, B, C of Biratnagar (Lat. -

Biratnagar Airport

BIRATNAGAR AIRPORT Brief Description Biratnagar Airport is located at north of Biratnagar Bazaar, Morang District of Province No. 1. and serves as a hub airport. This airport is the first certified aerodrome among domestic / Hub airports of Nepal and second after Tribhuvan International Airport. This airport is considered as the second busiest domestic airport in terms of passengers' movement after Pokhara airport. General Information Name BIRATNAGAR Location Indicator VNVT IATA Code BIR Aerodrome Reference Code 3C Aerodrome Reference Point 262903 N/0871552 E Province/District 1(One)/Morang Distance and Direction from City 5 Km North West Elevation 74.972 m. /245.94 ft. Off: 977-21461424 Tower: 977-21461641 Contact Fax: 977-21460155 AFS: VNVTYDYX E-mail: [email protected] Night Operation Facilities Available 16th Feb to 15th Nov 0600LT-1845LT Operation Hours 16th Nov to 15th Feb 0630LT-1800LT Status In Operation Year of Start of Operation 6 July, 1958 Serviceability All Weather Land Approx. 773698.99 m2 Re-fueling Facility Yes, by Nepal Oil Corporation Service Control Service Instrumental Flight Rule(IFR) Type of Traffic Permitted Visual Flight Rule (VFR) ATR72, CRJ200/700, DHC8, MA60, ATR42, JS-41, B190, Type of Aircraft D228, DHC6, L410, Y12 Buddha Air, Yeti Airlines, Shree Airlines, Nepal Airlines, Schedule Operating Airlines Saurya Airlines Schedule Connectivity Tumlingtar, Bhojpur, Kathmandu RFF Category V Infrastructure Condition Airside Runway Type of surface Bituminous Paved (Asphalt Concrete) Runway Dimension 1500 -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

Assessment of Nicotine Dependence Among Smokers in Nepal

Aryal et al. Tobacco Induced Diseases (2015) 13:26 DOI 10.1186/s12971-015-0053-8 RESEARCH Open Access Assessment of nicotine dependence among smokers in Nepal: a community based cross-sectional study Umesh Raj Aryal1*, Dharma Nand Bhatta2,3, Nirmala Shrestha1 and Anju Gautam3 Abstract Background: The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) and Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) are extensively used methods to measure the severity of nicotine dependence among smokers. The primary objective of the study was to assess the nicotine dependence amongst currently smoking Nepalese population. Methods: A community based cross-sectional study was conducted between August and November 2014. Information was collected using semi-structured questionnaire from three districts of Nepal. Data on demographic characteristics, history of tobacco use and level of nicotine dependence were collected from 587 smokers through face to face interviews and self-administered questionnaires. Non-parametric test were used to compare significant differences among different variables. Results: The median age of respondents was 28 (Inter-Quartile Range: 22–40) years and the median duration of smoking was 10 (5–15) years. Similarly, the median age for smoking initiation was 16 (13–20) years and the median smoking pack year was 4.2 (1.5–12). One third of the respondents consumed smokeless tobacco products. Half of the respondents wanted to quit smoking. The median score for FTND and HSI was 4 (2–5) and 2(0–3) respectively. There was significant difference in median FTND score with place of residence (p =0.03), year of smoking (p = 0.03), age at smoking initiation (p = 0.02), smoking pack year (p < 0.001) and consumption of smokeless products (p < 0.05). -

District Transport Master Plan (DTMP)

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Morang February 2013 Prepared by the District Technical Office (DTO) for Morang with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID i FOREWORD It is my great pleasure to introduce this District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Morang district especially for district road core network (DRCN). I believe that this document will be helpful in backstopping to Rural Transport Infrastructure Sector Wide Approach (RTI SWAp) through sustainable planning, resources mobilization, implementation and monitoring of the rural road sub-sector development. The document is anticipated to generate substantial employment opportunities for rural people through increased and reliable accessibility in on- farm and off-farm livelihood diversification, commercialization and industrialization of agriculture sector. In this context, rural road sector will play a fundamental role to strengthen and promote overall economic growth of this district through established and improved year round transport services reinforcing intra and inter-district linkages . Therefore, it is most crucial in executing rural road networks in a planned way as per the District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) by considering the framework of available resources in DDC comprising both internal and external sources. Viewing these aspects, DDC Morang has prepared the DTMP by focusing most of the available resources into upgrading and maintenance of the existing road networks. This document is also been assumed to be helpful to show the district road situations to the donor agencies through central government towards generating needy resources through basket fund approach. -

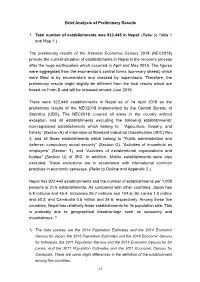

Brief Analysis of Preliminary Results

Brief Analysis of Preliminary Results 1. Total number of establishments was 922,445 in Nepal. (Refer to Table 1 and Map 1.) The preliminary results of the National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) provide the current situation of establishments in Nepal in the recovery process after the huge earthquakes which occurred in April and May 2015. The figures were aggregated from the enumerator’s control forms (summary sheets) which were filled in by enumerators and checked by supervisors. Therefore, the preliminary results might slightly be different from the final results which are based on Form B and will be released around June 2019. There were 922,445 establishments in Nepal as of 14 April 2018 as the preliminary results of the NEC2018 implemented by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). The NEC2018 covered all areas in the country without exception and all establishments excluding the following establishments: non-registered establishments which belong to “Agriculture, forestry, and fishery” (Section A) of International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) Rev. 4; and all those establishments which belong to “Public administration and defense; compulsory social security” (Section O), “Activities of household as employers” (Section T), and “Activities of extraterritorial organizations and bodies” (Section U) of ISIC. In addition, Mobile establishments were also excluded. These exclusions are in accordance with international common practices in economic censuses. (Refer to Outline and Appendix 2.) Nepal has 922,445 establishments and the number of establishments per 1,000 persons is 31.6 establishments. As compared with other countries, Japan has 5.8 millions and 45.4; Indonesia 26.7 millions and 104.6; Sri Lanka 1.0 million and 50.3; and Cambodia 0.5 million and 34.6; respectively. -

A Study on the Production of Cardamom Farming of Ilam District, Nepal

A STUDY ON THE PRODUCTION OF CARDAMOM FARMING OF ILAM DISTRICT, NEPAL A Thesis Submitted to Central Department of Economics, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ECONOMICS By MANISHA GADTAULA Roll No. : 15/2071 T.U.Regd.No. : 6-3-28-138-2014 Central Department of Economics Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal April, 2019 RECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled A Study on the Production of Cardamom Farming of Ilam District, Nepal is submitted by Manisha Gadtaula under my supervision for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Economics. I forward it with recommendation for approval. ........................................ Dr. Rashmee Rajkarnikar Thesis Supervisor Central Department of Economics Date: ii APPROVAL LETTER This thesis entitled A Study on the production of Cardamom Farming of Ilam District, Nepal submitted by Manisha Gadtaula has been evaluated and accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirement for the MASTER OF ARTS in ECONOMICS by evaluation committee comprised of: Evaluation Committee ........................................ Prof. Dr. Kushum Shakya Head of Department ........................................ External Examiner ........................................ Dr. Rashmee Rajkarnikar Thesis Supervisor Date: iii Federal Map of Ilam, Nepal iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis entitled A Study on the Production of Cardamom Farming of Ilam District, Nepal has been prepared for partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Economics. I would like to pay my sincere thanks and huge admiration to my thesis supervisor, Assistant Prof. Dr Rashmee Rajkarnikar, Central Department of Economics, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, for her continuous guidance, motivation, support, constructive, comments, and feedback throughout the research. -

Table of Province 01, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census 2018

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Taplejung District 4,653 13,225 7,337 5,888 10101PHAKTANLUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 539 1,178 672 506 10102MIKWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 269 639 419 220 10103MERINGDEN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 397 1,125 623 502 10104MAIWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 310 990 564 426 10105AATHARAI TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 433 1,770 837 933 10106PHUNGLING MUNICIPALITY 1,606 4,832 3,033 1,799 10107PATHIBHARA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 398 1,067 475 592 10108SIRIJANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 452 1,064 378 686 10109SIDINGBA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 249 560 336 224 Sankhuwasabha District 6,037 18,913 9,996 8,917 10201BHOTKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 294 989 541 448 10202MAKALU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 437 1,317 666 651 10203SILICHONG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 401 1,255 567 688 10204CHICHILA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 199 586 292 294 10205SABHAPOKHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 220 751 417 334 10206KHANDABARI MUNICIPALITY 1,913 6,024 3,281 2,743 10207PANCHAKHAPAN MUNICIPALITY 590 1,732 970 762 10208CHAINAPUR MUNICIPALITY 1,034 3,204 1,742 1,462 10209MADI MUNICIPALITY 421 1,354 596 758 10210DHARMADEVI MUNICIPALITY 528 1,701 924 777 Solukhumbu District 3,506 10,073 5,175 4,898 10301 KHUMBU PASANGLHAMU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 702 1,906 904 1,002 10302MAHAKULUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 369 985 464 521 10303SOTANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 265 787 421 366 10304DHUDHAKOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 263 802 416 386 10305 THULUNG DHUDHA KOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 456 1,286 652 634 10306NECHA SALYAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 353 1,054 509 545 10307SOLU DHUDHAKUNDA MUNICIPALITY -

OCHA Nepal Situation Overview

F OCHA Nepal Situation Overview Issue No. 19, covering the period 09 November -31 December 2007 Kathmandu, 31 December 2007 Highlights: • Consultations between the Seven Party Alliance (SPA) breaks political deadlock • Terai based Legislators pull out of government, Parliament • Political re-alignment in Terai underway • Security concerns in the Terai persist with new reports of extortion, threats and abductions • CPN-Maoist steps up extortion drive countrywide • The second phase of registration of CPN-Maoist combatants completed • Resignations by VDC Secretaries continue to affect the ‘reach of state’ • Humanitarian and Development actors continue to face access challenges • Displacements reported in Eastern Nepal • IASC 2008 Appeal completed CONTEXT Constituent Assembly. Consensus also started to emerge on the issue of electoral system to be used during the CA election. Politics and Major Developments On 19 November, the winter session of Interim parliament met Consultations were finalized on 23 December when the Seven but adjourned to 29 November to give time for more Party Alliance signed a 23-point agreement. The agreement negotiations and consensus on constitutional and political provided for the declaration of a republic subject to issues. implementation by the first meeting of the Constituent Assembly, a mixed electoral system with 60% of the members Citing failure of the government to address issues affecting of the CA to be elected through proportional system and 40% their community, four members of parliament from the through first-past-the-post system, and an increase in number Madhesi Community, including a cabinet minister affiliated of seats in the Constituent Assembly (CA) from the current 497 with different political parties resigned from their positions. -

Nepal's Birds 2010

Bird Conservation Nepal (BCN) Established in 1982, Bird Conservation BCN is a membership-based organisation Nepal (BCN) is the leading organisation in with a founding President, patrons, life Nepal, focusing on the conservation of birds, members, friends of BCN and active supporters. their habitats and sites. It seeks to promote Our membership provides strength to the interest in birds among the general public, society and is drawn from people of all walks OF THE STATE encourage research on birds, and identify of life from students, professionals, and major threats to birds’ continued survival. As a conservationists. Our members act collectively result, BCN is the foremost scientific authority to set the organisation’s strategic agenda. providing accurate information on birds and their habitats throughout Nepal. We provide We are committed to showing the value of birds scientific data and expertise on birds for the and their special relationship with people. As Government of Nepal through the Department such, we strongly advocate the need for peoples’ of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation participation as future stewards to attain long- Birds Nepal’s (DNPWC) and work closely in birds and term conservation goals. biodiversity conservation throughout the country. As the Nepalese Partner of BirdLife International, a network of more than 110 organisations around the world, BCN also works on a worldwide agenda to conserve the world’s birds and their habitats. 2010 Indicators for our changing world Indicators THE STATE OF Nepal’s Birds -

Biratnagar Initial Environmental Assessment

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 36188 November 2008 NEPAL: Preparing the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (Financed by the: Japan Special Fund and the Netherlands Trust Fund for the Water Financing Partnership Facility) Prepared by: Padeco Co. Ltd. in association with Metcon Consultants, Nepal Tokyo, Japan For Department of Urban Development and Building Construction This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. TA 7182-NEP PREPARING THE SECONDARY TOWNS INTEGRATED URBAN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT V o l u m e 17: BIRATNAGAR INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT in association with Environmental Assessment Document Draft Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: 36188 March 2010 Volume 17 Nepal: Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project – Biratnagar Subproject Prepared by Department of Urban Development and Building Construction, Ministry of Physical Planning and Works, Government of Nepal The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development