Kenema District Are Presented, Covering Local Responses to Health Issues, and Ebola in Particular

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Ebola Community Health Worker Programme Performance In

F1000Research 2019, 8:794 Last updated: 28 SEP 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE Post-Ebola Community Health Worker programme performance in Kenema District, Sierra Leone: A long way to go! [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Harold Thomas1, Katrina Hann 2, Mohamed Vandi1, Joseph Bengalie Sesay3, Koi Sylvester Alpha4, Robinah Najjemba 5 1Directorate of Health Security and Emergencies, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Freetown, Sierra Leone 2Sustainable Health Systems, Freetown, Sierra Leone 3Koinadugu District Health Management Team, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Kabala, Sierra Leone 4Kenema District Health Management Team, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Kenema, Sierra Leone 5Makerere University School of Public Health, Makerere, Uganda v1 First published: 06 Jun 2019, 8:794 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18677.1 Latest published: 09 Apr 2020, 8:794 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18677.2 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Background: The devastating 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra 1 2 Leone could erode the gains of the health system including the Community Health Worker (CHW) programme. We conducted a study version 2 to ascertain if the positive trend in reporting cases of malaria, (revision) report pneumonia and diarrhoea treated by CHWs in the post-Ebola period 09 Apr 2020 has been sustained 18 months post-Ebola. Methods: We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study using version 1 aggregated CHW programme data (2013-2017) from all Primary 06 Jun 2019 report report Health Units in Kenema district. Data was extracted from the District Health Information System and analysed using STATA. Data in the pre- (June 2013-April 2014), during- (June 2014-April 2015) and post-Ebola 1. -

2016 School List.Xlsx

emis_num Level Region Council Chfdom School Name Town phone owner 110101101 PRESCHOOL EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT CENTRE BAIWALLA 076593767 COMMUNITY 110101201 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 METHODIST PRIMARY BAIWALA BAIWALA 78963548 MISSION 110101202 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 NATIONAL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL BAOMA 078624877 MISSION 110101203 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 PROVINCIAL ISLAMIC DODO PRIMARY SCHOOL DODO TOWN 078451705 MISSION 110101205 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY NAGBENA 078360004 MISSION 110101206 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL SIENGA SIENGA 076484775 MISSION KAILAHUN DISTRICT EDUCATION COUNCIL PRIMARY 110101207 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 TAKPOIMA 79175290 GOVERNMENT SCHOOL 110101208 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL BAIWALLA 76606361 MISSION 110101209 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 KAILAHUN DISTRICT EDUCATION COMMITTEE KURANKO KURANKO 76735861 GOVERNMENT 110101210 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL SAKIEMA 078456779 MISSION 110101211 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL 076820424 MISSION 110101301 JSS EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 PEACE MEMORIAL JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL BAIWALLA 78540707 GOVERNMENT 110201101 PRESCHOOL EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 2 SUPREME ISLAMIC PRE‐SCHOOL DARU 77702647 MISSION EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT PRE‐ 110201102 -

Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

April 2008 NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume One February 2008 This page is intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Stages in the Ward Boundary Delimitation Process 7 Stage One: Establishment of methodology including drafting of regulations 7 Stage Two: Allocation of Local Councils seats to localities 13 Stage Three: Drawing of Boundaries 15 Stage Four: Sensitization of Stakeholders and General Public 16 Stage Five: Implement Ward Boundaries 17 Conclusion 18 APPENDICES A. Database for delimiting wards for the 2008 Local Council Elections 20 B. Methodology for delimiting ward boundaries using GIS technology 21 B1. Brief Explanation of Projection Methodology 22 C. Highest remainder allocation formula for apportioning seats to localities for the Local Council Elections 23 D. List of Tables Allocation of 475 Seats to 19 Local Councils using the highest remainder method 24 25% Population Deviation Range 26 Ward Numbering format 27 Summary Information on Wards 28 E. Local Council Ward Delimitation Maps showing: 81 (i) Wards and Population i (ii) Wards, Chiefdoms and sections EASTERN REGION 1. Kailahun District Council 81 2. Kenema City Council 83 3. Kenema District Council 85 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 87 5. Kono District Council 89 NORTHERN REGION 6. Makeni City Council 91 7. Bombali District Council 93 8. Kambia District Council 95 9. Koinadugu District Council 97 10. Port Loko District Council 99 11. Tonkolili District Council 101 SOUTHERN REGION 12. Bo City Council 103 13. Bo District Council 105 14. Bonthe Municipal Council 107 15. -

Kailahun District Constituencies And

NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation Process Process Delimitation Boundaries Constituency Electoral on Report NEC: 4.1.1 KAILAHUN DISTRICT CONSTITUENCIES AND POPULATION Eastern Region Constituency Maps 1103 a 43,427 m i a g g n K n e i o s T s T i i i s Penguia s K is is Yawei K K Luawa 1101 e 49,499 r 1104 1108 g n 33,457 54,363 o B Kpeje je e Upper West p K Bambara 1102 44,439 1107 Chiefdom Boundary 37,484 Constituency Code Njaluahun Mandu – 1101 Constituency 1 August 2006 August Dea 1102 Constituency 2 Jawie 1103 Constituency 3 1106 Malema 1104 Constituency 4 42,639 1105 Constituency 5 1105 1106 Constituency 6 52,882 1107 Constituency 7 1108 Constituency 8 42,639 Constituency Population PREPARED BY STATISTICS SIERRA LEONE KENEMA DISTRICT CONSTITUENCIES AND POPULATION Gorama Mende 1207 49,953 Wandor 1206 48,429 n u h Simbaru o g Lower le 1208 Dodo Bambara a M 54,312 1205 42,184 Kandu Leppiama 1204 51,486 1202 1201 42,262 Nongowa 43,308 # Small Bo # Kenema # 1203 1209 Town 42,832 44,045 Dama 1210 Niawa 36341 Gaura Langrama Koya 1211 Nomo 42,796 Chiefdom Boundary Constituency Code Tunkia 1201 Constituency 1 1202 Constituency 2 1203 Constituency 3 1204 Constituency 4 1205 Constituency 5 1206 Constituency 6 1207 Constituency 7 1208 Constituency 8 1209 Constituency 9 1210 Constituency 10 1211 Constituency 11 42,796 Constituency Population PREPARED BY STATISTICS SIERRA LEONE NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation Process – August 2006 NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation -

U N I T E D N a T I O

U N I T E D N A T I O N S Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs SIERRA LEONE HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT SEPTEMBER 2003 KEY EVENTS district. A concern raised in Kono is that none of the Watsan implementing partners had the facilities or machines for testing water • Yellow Fever outbreak samples. This has been reported to the MOHS. • Security Council extends UNAMSIL’s mandate • UN Agencies and GoSL celebrate World Peace Day SECURITY HIGHLIGHTS • Nigerian lawmakers call on UNAMSIL Overall security UNAMSIL (United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone) reports the overall security situation in HUMANITARIAN HIGHLIGHTS the country to be calm. However there have been some concerns about security along the Yellow Fever outbreak border regions, particularly along the Mano The Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS) River Union Bridge in the south. Similarly the has reported a total of 90 cases of Yellow Sierra Leone Police (SLP) are concerned Fever, from eight districts in the country: about the porous nature of the border in the Tonkolili, Bombali, Kenema, Koinadugu, Port Kamakwie, Tambakha and Koinadugu areas, Loko, Kambia and Kono. Of the 90 reported in the Northern Province that have resulted in cases (as of 29 September) four laboratory increased smuggling of goods across the cases were confirmed, all from the Tonkolili borders. The police have also reported hunters District, where majority of the suspected cases from Guinea, coming across, poaching and emanate from. Earlier, the MOHS gave out crossing back into Guinea. 100,000 doses of vaccine in four chiefdoms in the district. They have now finally secured UNAMSIL’s mandate extended funds to carry out mass immunization The UN Security Council has extended campaign in the remaining seven chiefdoms of UNAMSIL’s mandate, which was to expire on the district. -

The Constitution of Sierra Leone Act, 1991

CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT SUPPLEMENT TO THE SIERRA LEONE GAZETTE EXTRAORIDARY VOL. CXXXVIII, NO. 16 dated 18th April, 2007 CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT NO. 5 OF 2007 Published 18th April, 2007 THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991 (Act No. 6 of 1991) PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS (DECLARATION OF CONSTITUENCIES) Short tittle ORDER, 2007 In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by Subsection (1) of section 38 of the Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991, the Electoral Commission hereby makes the following Order:- For the purpose of electing the ordinary Members of Parliament, Division of Sierra Leone Sierra Leone is hereby divided into one hundred and twelve into Constituencies. constituencies as described in the Schedule. 2 3 Name and Code Description SCHEDULE of Constituency EASTERN REGION KAILAHUN DISTRICT Kailahun This Constituency comprises of the whole of upper Bambara and District part of Luawa Chiefdom with the following sections; Gao, Giehun, Costituency DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCIES 2 Lower Kpombali and Mende Buima. Name and Code Description of Constituency (NEC The constituency boundary starts in the northwest where the Chiefdom Const. 002) boundaries of Kpeje Bongre, Luawa and Upper Bambara meet. It follows the northern section boundary of Mende Buima and Giehun, then This constituency comprises of part of Luawa Chiefdom southwestern boundary of Upper Kpombali to meet the Guinea with the following sections: Baoma, Gbela, Luawa boundary. It follows the boundary southwestwards and south to where Foguiya, Mano-Sewallu, Mofindo, and Upper Kpombali. the Dea and Upper Bambara Chiefdom boundaries meet. It continues along the southern boundary of Upper Bambara west to the Chiefdom (NEC Const. The constituency boundary starts along the Guinea/ Sierra Leone boundaries of Kpeje Bongre and Mandu. -

A NEAR MISS? LESSONS LEARNT from the ALLOCATION of MINING LICENCES in the GOLA FOREST RESERVE in SIERRA LEONE.A

February 2010 A NEAR MISS? LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE ALLOCATION OF MINING LICENCES IN THE GOLA FOREST RESERVE IN SIERRA LEONE.a 1. INTRODUCTION Between 2005 and 2007 two mining licences were issued for diamond and iron ore prospecting in the Gola Forest Reserve in south-eastern Sierra Leone. The licences were granted even though the area was a proposed national park. It is likely that the allocation of the licences contravened Sierra Leonean law. There was minimal consultation with residents and the whole process was characterised by a worrying lack of transparency. The Gola Forest is one of the world’s most biodiversity-rich ecosystems. If mining were to have taken place, it would have been devastating for the environment. Furthermore, there were no guarantees that the residents of the area would gain sufficient economic benefits once mining began. Luckily, intervention from the President and the subsequent launch of the Transboundary Peace Park in May 2009 meant that to date, nothing has happened as a result of the licences and the immediate threat to Gola has been averted. However, the fact that the licences were allocated in the first place points to broad deficiencies in natural resource governance in Sierra Leone which must be addressed if the country is to develop sustainably and improve the lives of its citizens. Natural resources were key to funding the civil war in Sierra Leone between 1991 and 2002. This conflict saw many thousands killed or maimed by the rebel group, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), whose signature terror tactics included chopping off limbs and recruiting child soldiers. -

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June). -

Pygmy Hippo Conservation Project

Pygmy Hippo Conservation Project Within the “Across the River – A Transboundary Peace Park for Sierra Leone and Liberia” Project (ARTP) Sponsored by Zoo Basel, Switzerland First report, July – December 2010 Dr. Annika Hillers & Andrew M. Muana Across the River – A Transboundary Peace Park for Sierra Leone and Liberia (ARTP) Research Unit c/o Gola Forest Programme, 164 Dama Road, Kenema, Sierra Leone [email protected] Pygmy Hippo Conservation Project: First report July – December 2010 Zusammenfassung Das Zwergflusspferd-Schutzprojekt im “Across the River – A Transboundary Peace Park for Sierra Leone and Liberia” Projekt (ARTP) möchte in enger Zusammenarbeit mit den im Projektgebiet ansässigen Gemeinden Zwergflusspferde untersuchen und schützen. Das Projekt startete im Juli 2010. Das Team besteht aus einem Projektkoordinator, einem Verantwortlichen für Umwelterziehung und fünf „Community Conservation wardens“. Außerdem wird das Team von Kollegen der Forschungseinheit des ARTPs unterstützt. Die Community Wardens wurden in der Nutzung von GPS-Einheiten, Kompass, Fragebögen und Grundlagenwissen im Bereich Naturschutz und Zwergflusspferden geschult. Seit Juli 2010 sind sie regelmäßig im Feld und in den Dörfern unterwegs, um Daten zum Schutzstatus und zur Gefährdung von Zwergflusspferden (Jagd, Habitatzerstörung) sowie Informationen zu ihrer Ökologie (z.B. Ernährung und Bewegungsmuster) und bisher nicht bekannten Populationen zu sammeln. Geeignete Habitate entlang von Flüssen werden nach Kot-, Fuß- und Fressspuren abgesucht. Im Bereich Umwelterziehung kooperieren wir mit April Conway und der Environmental Foundation for Africa. Diese Kooperation beinhaltet das Erstellen von Materialien (z.B. Poster und Aufkleber) sowie gemeinsame Aktivitäten (z.B. Schulbesuche und „Road shows“ in den Dörfern). Für die zweite Hälfte des Projekts von Januar bis Juni 2011 planen wir, das Umwelterziehungsprogramm neben den bisherigen Aktivitäten auf das Erstellen von Zwergflusspferd-Wandmalereien auszuweiten. -

Sierraleone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

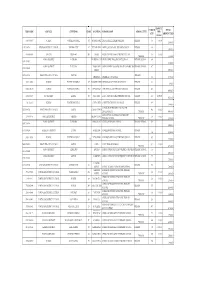

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume Two Meets and Bounds April 2008 Table of Contents Preface ii A. Eastern region 1. Kailahun District Council 1 2. Kenema City Council 9 3. Kenema District Council 12 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 22 5. Kono District Council 26 B. Northern Region 1. Makeni City Council 34 2. Bombali District Council 37 3. Kambia District Council 45 4. Koinadugu District Council 51 5. Port Loko District Council 57 6. Tonkolili District Council 66 C. Southern Region 1. Bo City Council 72 2. Bo District Council 75 3. Bonthe Municipal Council 80 4. Bonthe District Council 82 5. Moyamba District Council 86 6. Pujehun District Council 92 D. Western Region 1. Western Area Rural District Council 97 2. Freetown City Council 105 i Preface This part of the report on Electoral Ward Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each of the 394 Local Council Wards nationwide, comprising of Chiefdoms, Sections, Streets and other prominent features defining ward boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved wards _____________________________ Dr. Christiana A. M Thorpe Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chair ii CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT No………………………..of 2008 Published: THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2004 (Act No. 1 of 2004) THE KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL (ESTABLISHMENT OF LOCALITY AND DELIMITATION OF WARDS) Order, 2008 Short title In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (2) of Section 2 of the Local Government Act, 2004, the President, acting on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development and the National Electoral Commission, hereby makes the following Order:‐ 1. -

Sierra Leone's Journey to Self Reliance

BUILDING BACK BETTER: SIERRA LEONE’S JOURNEY TO SELF-RELIANCE COVER PHOTO: Qula Massaquoi, a cash transfer beneficiary in Boajibu, Kenema District, lost her son, his wife, and four grandchildren to Ebola virus disease. Her son’s two surviving children are now living with her, in addition to five other grandchildren. Despite all her losses, the sign on her door reads “Hope.” She says, “Where there is life, there must be hope.” Photo by Elie Gardner for Catholic Relief Services Building Back Better: SIERRA LEONE’S JOURNEY TO SELF-RELIANCE Building Back Better: Sierra Leone’s Journey to Self-Reliance © 2019 United States Agency for International Development (USAID). All rights reserved. This book was conceived under outgoing Country Coordinator Khadijat Mojidi, executed under the current leadership of Mission Director Jeff Bryan of USAID Guinea and Sierra Leone, and conceptualized by Mariama C. Keita, USAID Bureau for Africa, Office of West African Affairs. United State Agency for International Development (USAID)/Sierra Leone. (2019) Building Back Better: Sierra Leone’s Journey to Self-Reliance. Washington, DC: USAID. The Ebola Pillar II, Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning project is a three-year USAID-funded contract to assess USAID-coordinated efforts in mitigating the second-order impacts of the Ebola virus outbreak in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone between 2014 and 2016. The activity focuses on four main components: evaluation, routine monitoring, data quality assurance, and improved knowledge management and learning. Photography is credited throughout. Special thanks to photographers Elie Gardner (Catholic Relief Services), Joshua Yospyn (JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc.), and Michael Duff (USAID). -

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY