Diversity and Biogeography of Ferns and Birds in Bolivia: Applications of GIS Based Modelling Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity and Structure of Bird and Mammal Communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: Response to Agricultural Practices and Landscape Alterations

Diversity and structure of bird and mammal communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: response to agricultural practices and landscape alterations Julieta Decarre March 2015 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Division of Ecology and Evolution, Department of Life Sciences Imperial College London 2 Imperial College London Department of Life Sciences Diversity and structure of bird and mammal communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: response to agricultural practices and landscape alterations Supervised by Dr. Chris Carbone Dr. Cristina Banks-Leite Dr. Marcus Rowcliffe Imperial College London Institute of Zoology Zoological Society of London 3 Declaration of Originality I herewith certify that the work presented in this thesis is my own and all else is referenced appropriately. I have used the first-person plural in recognition of my supervisors’ contribution. People who provided less formal advice are named in the acknowledgments. Julieta Decarre 4 Copyright Declaration The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use it for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work 5 “ …and we wandered for about four hours across the dense forest…Along the path I could see several footprints of wild animals, peccaries, giant anteaters, lions, and the footprint of a tiger, that is the first one I saw.” - Emilio Budin, 19061 I dedicate this thesis To my mother and my father to Virginia, Juan Martin and Alejandro, for being there through space and time 1 Book: “Viajes de Emilio Budin: La Expedición al Chaco, 1906-1907”. -

Bolivia: the Andes and Chaco Lowlands

BOLIVIA: THE ANDES AND CHACO LOWLANDS TRIP REPORT OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2017 By Eduardo Ormaeche Blue-throated Macaw www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Bolivia, October/November 2017 Bolivia is probably one of the most exciting countries of South America, although one of the less-visited countries by birders due to the remoteness of some birding sites. But with a good birding itinerary and adequate ground logistics it is easy to enjoy the birding and admire the outstanding scenery of this wild country. During our 19-day itinerary we managed to record a list of 505 species, including most of the country and regional endemics expected for this tour. With a list of 22 species of parrots, this is one of the best countries in South America for Psittacidae with species like Blue-throated Macaw and Red-fronted Macaw, both Bolivian endemics. Other interesting species included the flightless Titicaca Grebe, Bolivian Blackbird, Bolivian Earthcreeper, Unicolored Thrush, Red-legged Seriema, Red-faced Guan, Dot-fronted Woodpecker, Olive-crowned Crescentchest, Black-hooded Sunbeam, Giant Hummingbird, White-eared Solitaire, Striated Antthrush, Toco Toucan, Greater Rhea, Brown Tinamou, and Cochabamba Mountain Finch, to name just a few. We started our birding holiday as soon as we arrived at the Viru Viru International Airport in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, birding the grassland habitats around the terminal. Despite the time of the day the airport grasslands provided us with an excellent introduction to Bolivian birds, including Red-winged Tinamou, White-bellied Nothura, Campo Flicker, Chopi Blackbird, Chotoy Spinetail, White Woodpecker, and even Greater Rhea, all during our first afternoon. -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

IGUAZU FALLS Extension 1-15 December 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report NW Argentina & Iguazu Falls: December 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour NW ARGENTINA: High Andes, Yungas and Monte Desert and IGUAZU FALLS Extension 1-15 December 2016 TOUR LEADER: ANDRES VASQUEZ (All Photos by Andres Vasquez) A combination of breathtaking landscapes and stunning birds are what define this tour. Clockwise from bottom left: Cerro de los 7 Colores in the Humahuaca Valley, a World Heritage Site; Wedge-tailed Hillstar at Yavi; Ochre-collared Piculet on the Iguazu Falls Extension; and one of the innumerable angles of one of the World’s-must-visit destinations, Iguazu Falls. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding Trip Report NW Argentina & Iguazu Falls: December 2016 Introduction: This is the only tour that I guide where I feel that the scenery is as impressive (or even surpasses) the birds themselves. This is not to say that the birds are dull on this tour, far from it. Some of the avian highlights included wonderfully jeweled hummingbirds like Wedge-tailed Hillstar and Red-tailed Comet; getting EXCELLENT views of 4 Tinamou species of, (a rare thing on all South American tours except this one); nearly 20 species of ducks, geese and swans, with highlights being repeated views of Torrent Ducks, the rare and oddly, parasitic Black-headed Duck, the beautiful Rosy-billed Pochard, and the mountain-dwelling Andean Goose. And we should not forget other popular bird features like 3 species of Flamingos on one lake, 11 species of Woodpeckers, including the hulking Cream-backed, colorful Yellow-fronted and minuscule Ochre-collared Piculet on the extension to Iguazu Falls. -

Supplemental Wing Shape and Dispersal Analysis

Data Supplement High dispersal ability inhibits speciation in a continental radiation of passerine birds Santiago Claramunt, Elizabeth P. Derryberry, J. V. Remsen, Jr. & Robb T. Brumfield Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA HAND-WING INDEX AND FLIGHT PERFORMANCE IN NEOTROPICAL FOREST BIRDS We investigated the relationship between wing shape and flight distances determined during 'dispersal challenge' experiments conducted in Gatun Lake in the Panama Canal (Moore et al. 2008). During the experiments, birds were released from a boat at incremental distances from shore and the distance flown or the success or failure in reaching the coast was recorded. To investigated the relationship between the hand-wing index and flight distance in Neotropical birds we used data on mean distance flown from table 3 in ref. We estimated hand-wing indices for the 10 species reported in those experiments (Table S1) . Wing measurements were taken by SC for four males of each species at LSUMNS. The relationship between the hand-wing index and distance flown was evaluated statistically using phylogenetic generalized least-squares (PGLS, Freckleton et al. 2002). We generated a phylogeny for the species involved in the experiment or an appropriate surrogate using DNA sequences of the slow-evolving RAG 1 gene from GenBank (Table S2). A maximum likelihood ultrametric tree was generated in PAUP* (Swofford 2003) using a GTR+! model of nucleotide substitution rates, empirical nucleotide frequencies, and enforcing a molecular clock. We found that the hand-wing index was strongly related to mean distance flown (R2 = 0.68, F = 20, d.f. -

BMC Evolutionary Biology

Convergent evolution, habitat shifts and variable diversification rates in the ovenbird- woodcreeper family (Furnariidae) Irestedt, M.; Fjeldså, Jon; Dalén, L.; Ericson, P.G.P. Published in: BMC Evolutionary Biology DOI: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-268 Publication date: 2009 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Dalén, L., & Ericson, P. G. P. (2009). Convergent evolution, habitat shifts and variable diversification rates in the ovenbird-woodcreeper family (Furnariidae). BMC Evolutionary Biology, 9(268). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-9-268 Download date: 03. okt.. 2021 BMC Evolutionary Biology BioMed Central Research article Open Access Convergent evolution, habitat shifts and variable diversification rates in the ovenbird-woodcreeper family (Furnariidae) Martin Irestedt*1, Jon Fjeldså2, Love Dalén1 and Per GP Ericson3 Address: 1Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 50007, SE-10405 Stockholm, Sweden, 2Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark and 3Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 50007, SE-10405 Stockholm, Sweden Email: Martin Irestedt* - [email protected]; Jon Fjeldså - [email protected]; Love Dalén - [email protected]; Per GP Ericson - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 21 November 2009 Received: 22 January 2009 Accepted: 21 November 2009 BMC Evolutionary Biology 2009, 9:268 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-268 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/9/268 © 2009 Irestedt et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Birding Santa Cruz, Bolivia's Largest Department

>> BIRDING SITES BIRDING SANTA CRUZ, BOLIVIA Birding Santa Cruz, Bolivia’s largest department Julián Quillén Vidoz and Daniel Alarcón Trilling Tapaculo Scytalopus parvirostris (daniel alarcón); difficult to see like other species in the genus, this skulker responded well to playback at Siberia For a landlocked country, Bolivia’s birdlist is nothing short of miraculous. Our authors take us from Amazonian lowlands to Andean highlands in search of the feathered treasures of Santa Cruz department 62 neotropical birding 7 anta Cruz is the largest department in Macaw Ara militaris (Vulnerable) can be Bolivia. It covers one-third of the country heard in the valleys during summer. S and is larger than nations like Ecuador, French Guyana and Suriname. Located in the Pampa Grande, Matarral and Comarapa east of the country, Santa Cruz borders Mato (150–220 km north-west of capital, c.200 species) Grosso (Brazil) to the east, the department of Leaving the capital, the ‘old road to Cochabamba’ Beni to the north, Cochabamba to the west, and passes through good birding habitat. From Chuquisaca and Paraguay to the south. The most the town of Pampa Grande, through Matarral, important city in the department is the capital, and up to Comarapa you traverse c.70 km Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Here, the visitor will of inter-Andean valleys dominated by xeric find accommodation and other services, and it is vegetation. Stop first at Pampa Grande, where also the best base from which to visit the rest of the best area is c.100 m before the town by the department. -

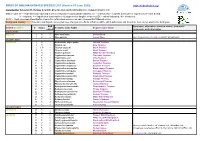

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Bolivia's Avian Riches 2016 BIRDS

Field Guides Tour Report Bolivia's Avian Riches 2016 Sep 3, 2016 to Sep 19, 2016 Dan Lane For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Seeing several Cream-backed Woodpeckers this well was definitely one of the highlights of the tour. Photo by participant Brian Stech. Bolivia, as per usual, didn’t disappoint with some amazing scenery, great birds, and the occasional logistical challenge. Roadwork caused a few delays but, on occasion, actually gave us an unexpected opportunity to see a good bird! That Hellmayr’s Pipit in Siberia and the side road to search (and successfully find!) Red-fronted Macaw and a few other targets along the Mizque were both happy results, for example. But the tour gave us some other great memories: high on the list were the astounding views of several Cream-backed Woodpeckers—a rather reasonable stand-in for the Ivory-billed! We also reveled in our luck with the difficult Scimitar-winged Piha, which showed in spades for us! The boldly-patterned White-eared Solitaire and the colorful Band-tailed Fruiteater were other birds that ranked high on our lists of species seen. Others we appreciated were the bold Brown Tinamou that crossed the track in front of us, the moxie of that male Andean Hillstar that inspected us up close, the majesty of the Andean Condors we saw on several days, the startling plumage of the Red-tailed Comet, and the equally captivating Black-hooded Sunbeam, the more muted beauty of the Cochabamba Mountain-Finch, and the escaped jailbird plumage of the Barred Fruiteater. -

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama Master of Philosophy, Remote Sensing Bachelor of Biological Sciences (Honours) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Biological Sciences Abstract Birds perform many types of migratory movements that vary remarkably both geographically and between taxa. Nevertheless, nomenclature and definitions of avian migrations are often not used consistently in the published literature, and the amount of information available varies widely between taxa. Although comprehensive global lists of migrants exist, these data oversimplify the breadth of types of avian movements, as species are classified into just a few broad classes of movements. A key knowledge gap exists in the literature concerning irregular, small-magnitude migrations, such as irruptive and nomadic, which have been little-studied compared with regular, long-distance, to-and- fro migrations. The inconsistency in the literature, oversimplification of migration categories in lists of migrants, and underestimation of the scope of avian migration types may hamper the use of available information on avian migrations in conservation decisions, extinction risk assessments and scientific research. In order to make sound conservation decisions, understanding species migratory movements is key, because migrants demand coordinated management strategies where protection must be achieved over a network of sites. In extinction risk assessments, the threatened status of migrants and non-migrants is assessed differently in the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, and the threatened status of migrants could be underestimated if information regarding their movements is inadequate. In scientific research, statistical techniques used to summarise relationships between species traits and other variables are data sensitive, and thus require accurate and precise data on species migratory movements to produce more reliable results. -

Automatic Classification of Furnariidae Species from the Paranaense Littoral Region Using Speech-Related Features and Machine Learning " Ecological Informatics , Vol

Automatic classification of Furnariidae species from the Paranaense Littoral region using speech-related features and machine learning∗ Enrique M. Albornoz,∗,a, Leandro D. Vignoloa, Juan A. Sarquisb, Evelina Leonb aResearch Institute for Signals, Systems and Computational Intelligence, sınc(i), UNL-CONICET. bNational Institute of Limnology, INALI, UNL-CONICET Abstract Over the last years, researchers have addressed the automatic classification of calling bird species. This is important for achieving more exhaustive environmental monitoring and for managing natural resources. Vocalisations help to identify new species, their natural history and macro-systematic relations, while com- puter systems allow the bird recognition process to be sped up and improved. In this study, an approach that uses state-of-the-art features designed for speech and speaker state recognition is presented. A method for voice activity detection was employed previous to feature extraction. Our analysis includes several clas- sification techniques (multilayer perceptrons, support vector machines and random forest) and compares their performance using different configurations to define the best classification method. The experimental results were validated in a cross-validation scheme, using 25 species of the family Furnariidae that inhabit the Paranaense Littoral region of Argentina (South America). The results show that a high classification rate, close to 90%, is obtained for this family in this Furnariidae group using the proposed features and classifiers. Key words: Bird sound classification, computational bioacoustics, machine learning, speech-related features, Furnariidae. 1 1. Introduction 13 number of problems associated with them, such as 14 poor sample representation in remote regions, ob- 2 Vocalisations are often the most noticeable man- 15 server bias [4], defective monitoring [5], and high 3 ifestations of the presence of avian species in dif- 16 costs of sampling on large spatial and temporal 4 ferent habitats [1]. -

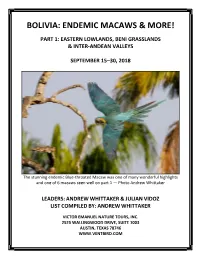

Bolivia: Endemic Macaws & More!

BOLIVIA: ENDEMIC MACAWS & MORE! PART 1: EASTERN LOWLANDS, BENI GRASSLANDS & INTER-ANDEAN VALLEYS SEPTEMBER 15–30, 2018 The stunning endemic Blue-throated Macaw was one of many wonderful highlights and one of 6 macaws seen well on part 1 — Photo Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & JULIAN VIDOZ LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM BOLIVIA: PART 1 EASTERN LOWLANDS, BENI GRASSLANDS & INTER-ANDEAN VALLEYS September 15–30, 2018 By Andrew Whittaker Bolivia quickly convinced us all that, without doubt, it is a truly magical birding paradise not to be missed! Amazingly and sadly, this terrific country still remains one of South America’s best-kept birding secrets. In fact, several of you kindly commented that these Bolivia trips had exceeded your wildest dreams, and you considered your Bolivian trip to have been the best South American birding trip ever (after having done many VENT trips to all the top bird-rich South America countries such as Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador)! Yes, this tiny landlocked country of Bolivia was simply as sensational as ever! Bird-rich Chaco of southern Bolivia – Photo Andrew Whittaker We enjoyed wonderful easy birding throughout both tours while visiting so many exciting and pristine biomes, even managing to smash VENT’S 40-year trip record of the largest ever birdlist! Bolivia part 1 ended with no less than 458 species while on Bolivia part 2 we enjoyed a further 341 species (with little overlap) giving people on both Bolivia tours an incredible total of 656 bird species and 12 Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Bolivia Part I, 2018 mammals in 23 days! Running down our list of top 7 birds on part 1 would make anyone drool.