Reginald Lawrence, Capuchin 1925 - 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tli Regiment ^ in the World

;,inMr^j^''aM.aaBslt iRaiga to. teiiiperatara toaIgM: . ’IMraday- falr ^ e a g ^ o e i i t o r . JUiycIwtor— C i f y o f V iU g g m (C fu k ta . _ fE IG H T E E N V a GES) PRICE THREE CENTS MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY; M ARCH 1?,.1941 (OtoaaMad Advarttotog Oa |Phga |8) ^^ VOL.LX.,N0^1SS - -V ' •- * Tliailand Boundary Settleirient' Greeks Beat • Ai.J u e s ts BiU H o u s e ' Back Italians M tte S ' I C l i l N X Blriclkshui: Units Storni Aft#r Gareful ^ Actiou: Taken Despite Batti^on W ip ^ , Out. S e e k s ^3i(K^,(K)0'(KW ^ {D^mUfrutic .Protests Ato*H>’-***«•» 18.—(fl-ttel-: British Fliers AiARiil Seen T o iatry.O u:t ■ >nnecti^V S h ri;u 1 d lana uMitg tha MggtHii fgrc6 to*y B u tk p ,Policy pC ^aU iri^ ^ Ribrisc- w » • *•» 'BL iteva tou* fur ampIojNidi Attacked different potote in Albante Attack Naval b A fn sp tH n g ntept Jo M atei for veli’i ^ Advanceriierit <tf yaatarday after c a r w l artillery praparatkinV hut alt thruate ;Were Holiday by Week. .’m pcracies' EyprV"0 ’ri* ^ repulaed,; Greek . tellltary' dla- ' Base at Kiel ( piarie And iRunitipji o f patchea aaJd today.'. Que$tion$ Vtdidity a f SUte GApitt^, HmrtJord, Faaclrt Blackshirt unit* atormed W ar .'We-.PG*sibly;:^in’ ^ ; March l.S.-HiA^The Gon^W; Acquisition ■ o f ' A r m y to* Gre,ek linea' ahoutlng “ AyantP varji'e Fire .aiul Heavv BrUish Ptemier 'Fi tm o l- ■Due’’—Forward for the ■ Lead-. -

Fall 2016 (PDF)

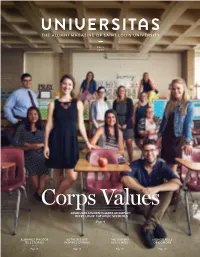

GRADUATE STUDENTS MAKE AN IMPACT ON ST. LOUIS’ CATHOLIC SCHOOLS Page 8 ALUMNUS’ PHOTOS AUTHOR’S LIFE THE LIBRARY HONOR ROLL TELL STORIES INSPIRES OTHERS ASSOCIATES OF DONORS Page 12 Page 14 Page 16 Page 19 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE VOLUME 43, ISSUE 1 EDITOR Laura Geiser (A&S ’90, Grad ’92) ASSOCIATE EDITOR Amy Garland (A&S ’97) ART DIRECTOR In September 1985, former Saint Louis University President Paul Matt Krob C. Reinert, S.J., wrote a piece for Momentum magazine on “The CONTRIBUTORS Spiritual Dimensions of Giving and Getting.” In an effort to show Emily Clemenson how philanthropy is ultimately tied to the love of God, human Marie Dilg (Grad SW ’94) Tina Haberberger growth and development, Father Reinert connected two ostensibly Maria Tsikalas opposing concepts: religious values and fundraising. Ultimately, he articulated that SLU’s ability to live our mission and achieve ON CAMPUS NEWS STORIES University Communications PHOTO BY STEVE DOLAN our goals relies heavily on the benevolence of our benefactors. Medical Center Communications First-year students await the start of convocation at Chaifetz Arena in August. nswering the call to live a life of service and service to SLU (page 3). When asked about her dedication Billiken Media Relations generosity is no easy feat. Father Reinert to the University, Mary said it was an “act of love.” The FEATURES SPECIAL INSERT admitted he would be unable to devote his way each of us shows our love toward the University dic- ON THE COVER life to the service of Saint Louis University tates the manner in which we choose to give of our gifts: Billiken Teacher Corps students 8 19 if he were not “genuinely committed to the our time, our resources and our knowledge. -

June-Oct 2021

JUNE-OCT FREE & BENEFIT 2021 PERFORMANCES SUMMERSTAGE.ORG SUMMERSTAGE NYCSUMMERSTAGE SUMMERSTAGENYC SUMMERSTAGE IS BACK More than a year after the first lockdown order, SummerStage is back, ready to once again use our city’s parks as gathering spaces to bring diverse and thriving communities together to find common ground through world-class arts and culture. We are committed to presenting a festival fully representing the city we serve - a roster of diverse artists, focused on gender equity and presenting distinct New York genres. This year, more than ever before, our festival will focus on renewal and resilience, reflective of our city and its continued evolution, featuring artists that are NYC-born, based, or inextricably linked to the city itself. Performers like SummerStage veteran Patti Smith, an icon of the city’s resilient rebelliousness, Brooklyn’s Antibalas, who have married afrobeat with New York City’s Latin soul, and hip hop duo Armand Hammer, two of today’s most important leaders of New York’s rap underground. And, as a perfect symbol of rebirth, Sun Ra’s Arkestra returns to our stage in this year of reopening, 35 years after they performed our very first concert, bringing their ethereal afro-futurist cosmic jazz vibes back to remind us of our ongoing mission and purpose. Our festival art this year also reflects our outlook -- bold, bright, powerful -- and was created by New Yorker Lyne Lucien, an award-winning Haitian artist based in Brooklyn. Lucien is an American Illustration Award Winner and a finalist for the Artbridge - Not a Monolith Residency. She has worked as a photo editor and art director at various publications including New York Magazine, The Daily Beast and Architectural Digest. -

Circus Report, March 24, 1980, Vol. 9, No. 12

«£• 9th Year March 24,1980 Number 12 AVAILABLE ,-OW L M/ r ;fcNv.:AG£ MfN'S KAYE HOLLYWOOD ELEPHANTS PAUL V. KAYE f f fSuiit 51S • 1680 North Vine Str*»!t • Hollywood. California • 90028 Area Coo«.- 213 • 462-6001 Page 2 March 24, 1980 Joseph C. Reisinger ATTORNEY AT LAW Elephant Ride Entertainment Law - Civil Trials - Immigration FOR HIRE For Free Consultation or Appointment Large, Gentle Elephant Call: 415-472- 1050 Clean Operation Contact: SMOKEY JONES ANGELA WILNOW and her Collies worked se- (714)829 - 1856 veral dates in Florida during the week of March 10th fcrWm. Garden Enterprises, booked by the Amandis Agency. In Memoriam-? JOHN Mac KAY. clown, has been signed for the HARRY BAKER (86), juggler and vaudeville M & M dates at Omaha and Lincoln, and for the star for more than 70 years, died on Feb. 23rd St. Louis show, as well as for a date in Toledo. at Stockton, Calif., after a long illness. Baker BOB HOPE, comedian, starred in an Easter Seal started juggling at the age of 12 and performed Benefit program at Tampa, Fla. on Mar. 14th. in vaudeville with such people as Milton Berle, Jimmy Durante, Jack Haley and others. JOHNNY GATES, of Houston, and "Naler" of Mexico City presented a full evening program He met his wife, Peggy, in 1939 in England. of magic with a spook show at La Margue, Tex- They married and she joined his juggling act. as for the Jaycees this past month. They remained in England until 1950 when they came to the U. S. -

No Radical Hangover: Black Power, New Left, and Progressive Politics in the Midwest, 1967-1989

No Radical Hangover: Black Power, New Left, and Progressive Politics in the Midwest, 1967-1989 By Austin McCoy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Matthew J. Countryman, Co-Chair Associate Professor Matthew D. Lassiter, Co-Chair Professor Howard Brick Associate Professor Stephen Ward Dedicated to Mom, Dad, Brandenn, Jeff, and K.C., all of the workers who have had their jobs stolen, and to all of the activists searching for answers. ii Acknowledgements Since I have taken the scenic route to this point, I have many thanks to give to family, friends, and various colleagues, collaborators, and communities that I have visited along the way. First, I would like to thank my dissertation committee—Howard Brick, Stephen Ward, Matt Lassiter, and Matthew Countryman. Your guidance and support enhanced this my dissertation. Your critical comments serve a cornerstone for this project as I proceed to revise it into a book manuscript. Howard, your classes and our conversations have expanded my thinking about the history of the left and political economy. Stephen, I appreciate your support for my scholarship and the fact that you always encouraged me to strike a balance between my academic and political work. Matt, I have learned much from you intellectually and professionally over the last seven years. I especially valued the fact that you gave me space and freedom to develop an ambitious project and to pursue my work outside of the classroom. I look forward to your continued mentorship. -

NGA | 2012 Annual Report

NA TIO NAL G AL LER Y O F A R T 2012 ANNUAL REPort 1 ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2012) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Leo A. Daly III Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher John Wilmerding Juliet C. Folger Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Lenore Greenberg Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Timothy F. Geithner Richard C. Hedreen Secretary of the Treasury Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke John Wilmerding Victoria P. Sant Helen Henderson Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Benjamin R. Jacobs Victoria P. Sant Sheila C. Johnson John Wilmerding Betsy K. Karel Linda H. Kaufman AUDIT COMMITTEE Robert L. Kirk Frederick W. Beinecke Leonard A. Lauder Chairman LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Timothy F. Geithner Secretary of the Treasury Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Diane A. Nixon John G. Pappajohn Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant Sally E. Pingree John Wilmerding Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu Andrew M. Saul John C. Fontaine Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson Benjamin F. Stapleton Luther M. Stovall Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Roberts Jr. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Ladislaus von Hoffmann Chief Justice of the Diana Walker United States Victoria P. Sant President Alice L. -

Pka S&D 1952 Mar

Your Jeweled Sweetheart Pin Will Be Her Most Treasured Gzft Your sweetheart will alwa ys treasure and cherish a beautiful jeweled pin. Whether it is set with rubies or emeralds from Burma and India, diamonds from South Africa or genuine Ori ental pearls from India, it will be a beautiful symbol of your love and regard. Many chapters present a jeweled pin to their IIKA "Dream Girl" at the annual winter formal or "Dream Girl Dance." The No. 0 size is the most popular Sweetheart pin size. Send Your Order T oday! PRICE LIST No. 0 No. I No.2 No.3 Plain border badge .......................................... $ 5.25 $ 6.25 $ 6.75 $ .... _ Nugget, chased o r engraved border badge .............................................. 5.75 6.75 7.25 C lose set pearl bad ge .................................... 10.00 10.50 11.50 19.00 CROWN SET JEWELED BADGES Al l-pearl ···················································-·······--· 13 .00 15.00 17 .50 24.00 Pearl with ruby or sapphi re poi nts................ 14.00 16.25 19.00 26.00 Pearl with emera ld po ints ···················-·······-·· 16.00 18.00 21.50 30.00 A lternate pearl and ruby o r sapphire........ 15.00 17 .50 20.75 28.00 Alternate pea rl and eme rald ........................ 19.00 21.00 25 .50 36.00 All -ruby o r sapphire ........................................ 17.00 19.75 24 .00 32.00 Rub y o r sapphire wit h dia mond points........ 30.50 38.50 50.75 78. 75 All -emera ld .......................................................... 25.00 27.00 33.50 48 .00 Pledge button ........................................................................................ $ .SO La rge pledge button ......................................................................... -

The NCAA News

The NCAA News Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association March 10, 1993, Volume 30, Number 10 Procedures set by Commission’s new liaison panel The NCAA Prrsidents Commis- broad-based hearing opportunity. sion Liaison (:ommittce has estab- ‘I’hr I.iaison Committee ag-reed lishcd the procrdurrs that it will 10 mrrt twice a year, conducting use in serving ;U a hearing panel hrarings with al)prnpGtc groups tar constiturnt groups to exprf2s as rrquesred at each of the meet- their views to the Commission. ings. This year’s meetings will be The 11 -member rommittcc, held June XL]uly I in Kansas City, which includes fat ulty athletics Missouri (at the conclusion of the rrprcsentatives and athletirs ad- summer meeting of the Presidents ministrators in addition to five Comnilssion), an d in September membrr s ofthc Commission, con- in Dallas, with the exact dates 20 be ducted an organizational meeting determined. In the future, the plan March 2 in Dallas. The committee is to meet in ApTi and September is chaired by Commission mcmht-r each year, but the committee did Richard E. l&k, president of the not believe there was sufficient LJniversity of Nrw Mexico. time 10 assure an effective April It was established by the Corn- meeting rhis yrar. mission to provide a more rffrctivc The committee also rccrivrd its and more broad-based means of first request for an apprardnce hearing from the various constitu- and gramed it. The National Asso- Title winner ent groups in college athletics. In ciation of Basketball Coaches will Jim Gale (top) of Mankato State University got the best of Trent Snyder of Western State College the past, the full Commission has be scheduled for an appearance of Colorado-but just barely. -

The Davie Record

The Davie Record DAVIE COUNTY’S OLDEST NEW SPAPEB-THE PAPER P e o p l e h e a d mHERE SHALL THE PF'SS. THE PEOPLE’S RIGHTS MAINTAIN: UNAWCO BY INFLUENCE AN ll UNBRIBED BY CAIN " VOLUMN L. MOCKSVILLE. NORTH CAROLINA, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 5 1050. NUMBER 36 NEWS OF LONG AGO. TheMan WhoLives Control Blue Mold Seen Along Main Street SevenDeadIySins By Thn Street Rambler. What Was Happening In Da Blue Mold has already appeared OOOOOO To Do God's Witt in Eastern counties and will prob vie Before Parking Meier* Herbert Eidson discussing court Rev. Walter E. Isenbour. Hitfh Point. R 4. ably move west in the near future. And Abbreviated1Skirl*. PutOntoCanvas Shortage of plants in 1949 caused proceedings -H . R. Johnson look The man who lives to do God’s will ing over new spring line of men’s (Davie Record, April 4, 1934.) And proves quite true along the LfNES tobacco farmers a lot of expense, and loss of money at sale time. suits - Mrs. Paul Hendrix and Miss Miss Bthel Butler spent the East w ay. ByNotedPainter Cornelia Hendrix going down De er holidays with her parents at Though oftentimes he sufiers 111, Blue Mold cannot be cured but NEW YORK.—What are the ' pot street at luncheon hour—At: Reldsville. And finds it hard sometimes to “seven deadly sins?” j it can be prevented. Plants should be treated when the size of a dime. tomey Allie Hayes out looking “ Buck” Allison, of Wilmington, p ray . An artist has put them on can- i for votes - Duke Whittaker hang spent Easter in town with home Yet holds t 0 G od’s u nchanging vas. -

The American Giallo

Georgi Wehr THE AMERICAN GIALLO The Italian Giallo and its Influence on North-American Cinema DOCTORAL THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doktor der Philosophie Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften Supervisor Assoc.-Prof. PD Dr. Angela Fabris Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Romanistik Supervisor Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jörg Helbig, M.A. Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Evaluator Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jörg Helbig, M.A. Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Evaluator Assoc. Prof. Srećko Jurišić University of Split Klagenfurt, February 2020 i Affidavit I hereby declare in lieu of an oath that - the submitted academic paper is entirely my own work and that no auxiliary materials have been used other than those indicated, - I have fully disclosed all assistance received from third parties during the process of writing the thesis, including any significant advice from supervisors, - any contents taken from the works of third parties or my own works that have been included either literally or in spirit have been appropriately marked and the respective source of the information has been clearly identified with precise bibliographical refer- ences (e.g. in footnotes), - to date, I have not submitted this paper to an examining authority either in Austria or abroad and that - when passing on copies of the academic thesis (e.g. in bound, printed or digital form), I will ensure that each copy is fully consistent with the submitted digital version. I understand that the digital version of the academic thesis submitted will be used for the purpose of conducting a plagiarism assessment. -

Colorado Springs, Entered Pews and Kneelers Were Pur the Christian Brothers’ Noviti ST

Minority of 8,000,000 DENVERaTHaiC Striving for Their Rights REGISTER Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations By Paul Page "The Puerto Ricans in New York and the THURSDAY. OCT. 17, 1963 DENVER, COLORADO VOL. LVIll No. 10 THE STRUGGLE of 20,000,000 Ameri northeastern United States, the Cuban exiles, can Negroes to shed the onus of “ second- the Mexican Americans in the Southwest, the class citizenship” is a 20th century social thousands of migrant laborers, and the many permanent Spanish residents across the conti revolution that has captured the eyes and nent. have varied outlooks, interests, and live ears of the whole world. Teachers Key lihoods. They do have, however, a common bond It overshadows the struggle of another of Catholicity. minority group—8,000,000 Spanish-Ameri- "I believe most sincerely, that the establish cans. ment of Leal councils for the Spanish-speaking This is a view of Father Theodore E. is of great importance to the welfare of 8.000.000 To Future of McCarrick, president of the National Council Spanish \mericans” the 32-year-old pnest said foi the Spanish-speaking, Catholic University movingly. of America. “ I don’t think that the greatest progress will “ Spanish Americans as a group are not be made in Washington or New York or San U.S, W orld resentful or envious of the Negro.” he told the Antonio or Denver, but at councils at the local Register, “ but they do want to join in a similar level where Spanish-Americans and Anglo- THE DEDICATED WORK OF teachers to movement to better themselves socially and Americans can sit down and work together day "may well provide the key to the success economically.” observing what the problems are and try to or the failure of our nation’s leadership in the Father McCarrick was attending a two-day find solutims for them.” world.” regional conference here of diocesan directors This was the message of Lt. -

Brian Cassidy Bookseller @ Cover: International Klein Blue (IKB), Item #4

brian cassidy bookseller @ Cover: International Klein Blue (IKB), item #4. bcb @ tpm is the counterculture department of Type Punch Matrix, a rare book firm founded by Rebecca Romney and Brian Cassidy. Cataloguing by: Allie Alvis, Brian Cassidy, Rebecca Romney, and Zoë Selengut (especially item #1). Photography by Rebecca Romney. Design: Brian Cassidy. Printed by Covington Group, May 2021. We strive to be inclusive and accurate in all of our cataloguing. If you encounter descriptions you feel misrepresent or omit important perspectives, or use language that could be improved, please email us. (Item 12) type punch matrix [email protected] Terms Additional images of available items are viewable on our website (www. typepunchmatrix.com). All items are original (meaning not facsimiles or reproductions) first editions (i.e. first printings), unless otherwise noted, and are guaranteed as described. Measurements are height x width in inches rounded to the nearest quarter inch. Prices in US dollars. All material subject to prior sale. Returnable for any reason within 30 days, with notification and prompt shipment. Payment by check, money order, or wire; Visa, Amex, MasterCard, Discover, and PayPal also accepted. Domestic ground shipping is free for all orders over $250; surface international shipping free for orders over $500. Else postage billed. Sales tax added to applicable purchases. Reciprocal courtesies to the trade. Type Punch Matrix is an ABAA- and ILAB-member firm and upholds their Codes of Ethics. (Item 1) featured 1. Teenage Dreamworld As Archive Alternate Universe Record Collection [Anonymous] [circa 1986-1990] Stunning and extensive collection of original artwork, album covers, and two lengthy reference books — all describing a vast imaginary world of 20th-century rock-and-roll that never existed.